Meet A ‘Blue Planet’ Sub Pilot

From the first filming of a live giant squid to underwater lakes, Buck Taylor has seen it all.

This is a part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

This is a part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

You’ve likely seen some amazing underwater documentary footage from places like BBC’s Blue Planet and Discovery Channel. But have you ever wondered about the submarine pilots who make that footage possible in the first place?

Meet Mark “Buck” Taylor, the sub team leader for the research and exploration vessel Alucia. Buck is responsible for carrying out all the submersible operations aboard the ship. The Alucia facilitates missions for both scientific research and serves as a home base for documentary productions like Blue Planet.

Buck started his career far away from cameras as an explosive ordnance device diver for the British Navy. After that, he was a submarine rescue pilot and transitioned to documentary and scientific research.

We sat down with him to talk about what it’s like doing science at the bottom of the sea, capturing the first footage of a living giant squid, and how the ocean still amazes him.

This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Can you put me in your place, emotionally, throughout a dive?

One of the nicest things about a dive is when the hatch shuts. You get locked away from the outside world. Suddenly, there are no more emails. There’s just the job at hand.

“You can imagine what you’re going to see, but you never fully appreciate it until it’s right in front of you.”

And when you’re there, you’re in the moment. We’ll normally spend about 10 to 12 hours in the water when we’re filming or doing science. It takes an hour to get down to 3,300 feet and an hour to get back, so we’re normally eight to 10 hours on the bottom. And you’ll be in the moment. You’ll be looking at a monitor or filming or you’ll be taking samples and sometimes you can’t appreciate it till you come back and you watch the footage again, and it just literally blows you away. Sometimes it’s too much for the senses to take in.

But, there’s a lot of planning that goes into these dives. We’ll map an area with the ship first and decide exactly where we want to dive. So even before we’ve seen it, we have a good sense of what we’re going to find down there. But even so, you can imagine what you’re going to see, but you never fully appreciate it until it’s right in front of you.

There is a sense of excitement. I would say that 99 percent of the time we never dive on the same site more than once. So, every dive we’re doing, we’re the first people witnessing things that have never been seen by anyone before. And seeing new fish, creatures, critters, corals that have never been described before. So, absolutely, there’s a huge sense of excitement before any dive.

What are some of the most surprising things you’ve encountered underwater?

There are three [things] that really stand out. I was privileged enough last year to dive in Antarctica and we didn’t really know what to expect. We were the first people to dive subs in the Weddell Sea. We were the first manned subs to get to a thousand meters (3,300 feet). And we were completely blown away with the amount of life that we found at depth.

Generally, when we dive around the world, you’ll get these big bands of life from the surface down to 50, 60, maybe even 100 feet, and then it sort of gradually dies off. But in Antarctica, it’s the polar opposite. There was life on the surface, but as soon as we got to [the assigned] depth it was absolutely stunning. And I stayed in Antarctica for three months and I don’t think there was a single dive there that disappointed at all. So, it was amazing.

[This company wants to bring mini science museums to you.]

And then during BBC Blue Planet II, we were filming in the Gulf of Mexico. We filmed a mud volcano and a brine pool. Witnessing this huge volcano erupting and letting off big methane bubbles was just stunning. We were blown away by how much we saw.

And then the brine pools. A brine pool is basically a lake at the bottom of the ocean, because the water is just super saline. You can watch all the animals interacting with this lake. Some of them use it to hunt because they know that any fish that touch it generally are going to die. They’ll use it to their advantage. So, on this huge abyssal plain where there was no life at all, suddenly you came across a single brine pool and it was just an oasis of life. The animals were coming in from all directions and congregating around this area.

Do you constantly run into amazing things or is the reality of a dive more mundane?

It definitely depends where you are. On one end of the spectrum, in Antarctica, we didn’t have to move at all; there was just life everywhere. Then at the other end, we spent a month in Australia off the Great Barrier Reef to film an aggregation of lantern fish, which is the largest fish aggregation on the planet. In a month’s worth of diving, 12 hours a day, we didn’t see one lantern fish at all. Very, very frustrating.

The same can be said for the giant squid trip in 2012. We were the first vessel to film the giant squid, off the Ogasawara islands in Japan. We spent a month filming every day in the water for 12 hours. And we had a single encounter for 18 minutes and that was enough to make three documentaries. That single encounter came only two days before the end of the charter. At that point, some people were panicking and some people were sort of giving up, thinking it was completely impossible.

So, it will go from complete boredom to complete excitement in a second and then it’s gone again and we’re just sat there thinking, did that actually happen?

Credit: Buck Taylor

In addition to diving with film crews, you often take scientists with you. What’s it like diving with them?

Many times, we’re diving in new areas nobody has ever seen before. And just to take scientists down there and see them react is tremendous.

One time, we were at a sea mountain in Panama and the visibility was stunning. We could see this cloud of sediment coming towards us down current and we thought, “Wow, that’s ridiculous.”

And just by chance, we drove towards the cloud, and there was this huge marching aggregation of crabs. And I mean millions upon millions of crabs. And the scientist we were with studied crabs and his jaw hit the floor because, number one, he didn’t know that happened. And number two, it probably happens once a year and we were sat there in the middle of this aggregation witnessing it.

“I had a fire inside a submersible once. I was up to my waist in seawater once. To be a sub pilot, you have to be a very calm person.”

What evidence of climate change have you seen?

We do see plastics and evidence of general garbage in the ocean all over the planet. It’s very sad. We saw plastic strapped to the side of icebergs in Antarctica, which you wouldn’t expect. We found big, huge balls of fishing net right in the middle of the marine reserves in the Galapagos, which shouldn’t be there. It is frustrating at times. It’s so hard.

I think that Blue Planet has done a good job of bringing awareness to the use of single-use plastics. But there’s still a lot to do. There are a lot of countries out there who are still using lots of single-use plastics. It’s frustrating seeing it, but hopefully that message can be put out there and something can be done about it.

Have there been moments of danger in the sub?

On Blue Planet, they showed that we had a small leak. It was slightly dramatized for the screen, which isn’t always useful for our cause, but it makes good television.

I was an ex-British Navy diver and then I got into submarine rescue. So I’d drive little submarines that would lock onto military submarines if they had an accident and take the people out. So during that period of my life, I had moments.

I had a fire inside a submersible once. I was up to my waist in seawater once. To be a sub pilot, you have to be a very calm person. And when we’re training people, it’s one of the first things we do. We put people under a lot of pressure and see how they react, because when you’re having problems, they can get out of hand very quickly. You need somebody who can stop, relax, sit back, and work through the problem methodically. Rather than throwing their arms up in the air and panicking.

Why did you want to join the Navy?

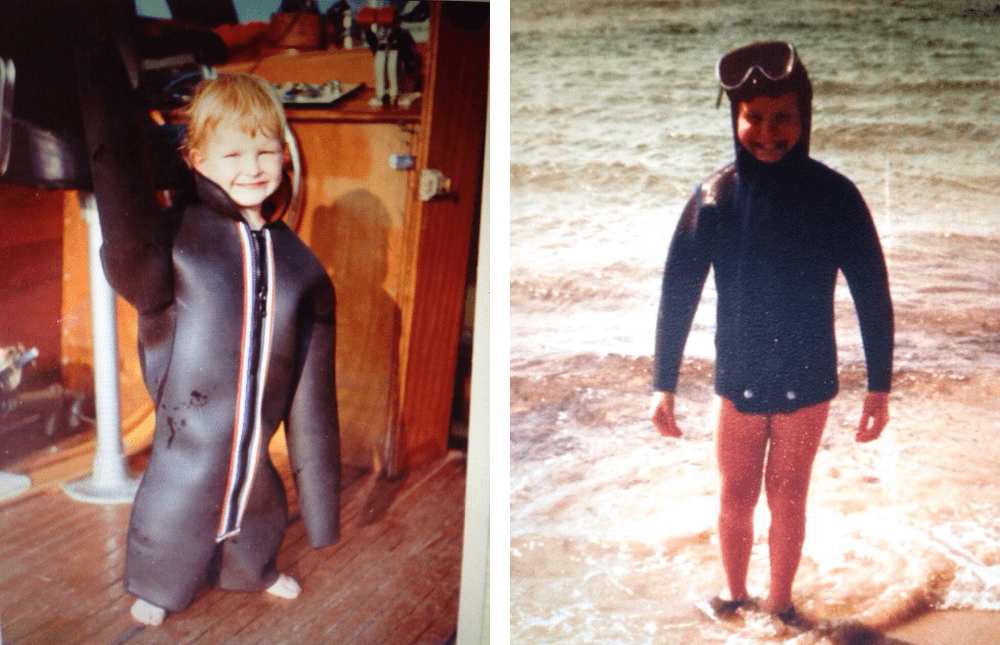

I joined the Navy as a diver. There are some great pictures of me at about seven or eight in a wetsuit in the frigid waters of the U.K., wanting to go snorkeling every weekend. So, from as long as I can remember, I had this huge connection with the ocean. I think everybody in my family knew it was a foregone conclusion that I would end up professionally in the water one way or another.

Buck as a kid. Credit: Buck Taylor

I went to college to study mechanical engineering. And after that, I joined the Navy as an explosive ordnance disposal diver, mine clearance. I managed to survive that. I was actually in the Navy for 14 years. But during the last five years, I was attached to submarine rescue and submersible operations.

And then in 2000, the Russian submarine, the Kursk, had a torpedo explode in its tubes. We got sent out for that. But the Russians wouldn’t let us dive [and rescue] because of politics. It was very frustrating.

After that, I left the Navy and transitioned from that to diving science and media. So that’s what brought me to where I am now. No regrets. I wouldn’t go back to submarine rescue because I love what I’m doing now. And you actually get to see some nice sights rather than just black, frigid water all the time.

So, you did sub rescue work for a while. And then, how did you start working on TV documentaries and science expeditions?

So, the number one thing was being able to pilot a submersible, I had that skill set already. People often ask me you know how they can become a submersible pilot. One of the key things I didn’t really appreciate at the time was having some sort of mechanical or electrical background. Because I studied mechanical engineering in college, that’s helped me to no end. But generally, all of our pilots [on the Alucia] have either a mechanical or electrical background. The exception to that is one guy who’s a marine biologist.

Do you have any kids? If you do, do they enjoy watching the documentaries you work on?

Yes, I do have one. He’s a big kid, 21 years old. He just graduated from university in Perth in Australia. I think I’ve sort of inspired him, so much so that his degree is in production and he wants to get into documentary making. He doesn’t want to be a submersible pilot; he’s realized that’s not for sensible people. He wants to get into natural history documentary, but not necessarily the ocean. I’m very proud of him.

What’s your favorite thing about the ocean?

It never ceases to amaze me, how powerful it is, how vast it is, how little we know about it, and how small it can make you very, very quickly. I have the ultimate respect for the ocean.

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.