Mapping The Journey Of Marine Animal Migrations

Locked within each map is a story.

This is a part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

This is a part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

Deep under the sea and across vast expanses of ocean out of our sight, animals are moving unceasingly in great migrations. They’re going about their lives—feeding, nesting, birthing—and creating maps of their existence. And within each of those maps and migrations is a story. That’s what designer Oliver Uberti first realized on land when he heard about an elephant named Annie.

In 2006, Annie traversed southeastern Chad in Central Africa. She moved 1,000 miles in 86 days. She left park boundaries and followed the rainfall to seek out the lushest vegetation. She waited until nightfall to cross roads in order to minimize contact with poachers. And then, she stopped. When researchers arrived at Annie’s GPS collar’s last recorded location, they discovered that she had been poached.

This was the story that Uberti, who was working for National Geographic at the time, was tasked with telling in the form of a map. When Annie’s movements were represented on the map, they were more than just a series of red dots.

[These tiny swimmers may stir the sea.]

“This was the first time that a map had ever connected me to the life of an individual animal,” Uberti says. And as the years went on, he found himself remembering Annie. He thought to himself: “What if we did find more researchers and more studies all around the world, and pool together more maps of the lives of individual animals?”

He partnered with geographer and cartographer James Cheshire of University College London and did just that, mapping out the stories of animals moving all around our planet in the book Where The Animals Go. And they went beyond the constraints of land—the book plunges readers into the ocean, alongside the creatures that make treks across the planet, out of our sight.

“Every day we hear more and more and more about data and big data and how new kinds of data are transforming how we understand the world,” Cheshire says. “Maps and data graphics are kind of a window into this new world.”

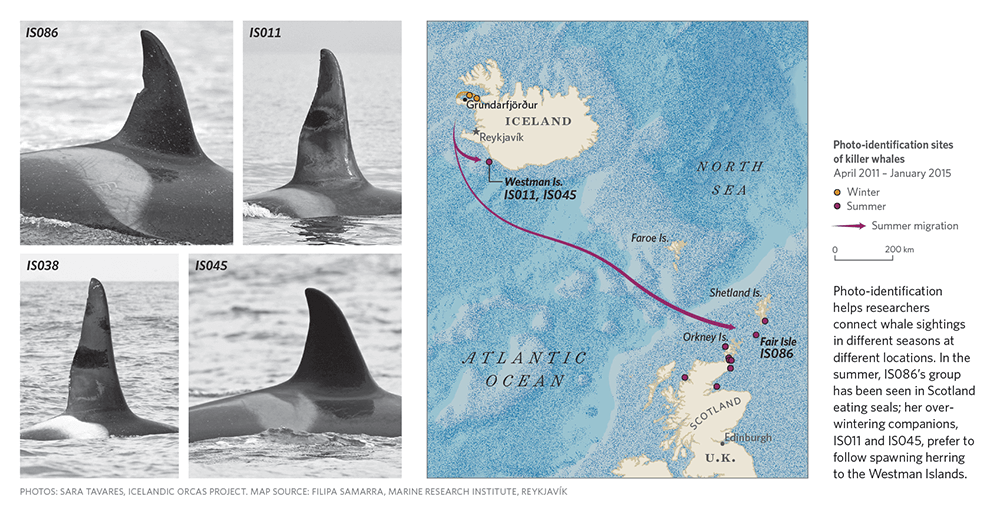

James Cheshire and a team of researchers found themselves stuck on a broken-down boat off the south coast of Iceland in 2016. Cheshire was trying to get a sense of how the researchers do their work as they tried to solve a mystery: Why were some of the orca whales that normally take up residence near Iceland showing up in Scotland waters? They had a hunch that those whales were hungry for more than just their typical meal of herring—and traveling to Scotland to accommodate their changed diet.

Back at camp, Filipa Samarra, a whale researcher from the Marine Research Institute in Reykjavík, checked Facebook. Someone had posted a video of the whales that her team was observing to a Facebook group for whale watchers. The whales in the video were feeding on gray seals, confirming the researchers’ hunch.

“That was kind of the start of us realizing that the members of the public could be really useful for tracking these movements back and forth,” Samarra says.

[Meet a ‘Blue Planet’ submarine pilot.]

Now, Samarra and her team incorporate citizen science into their work on various projects. That’s possible because of the low-cost, low-tech tracking methods that they use—they visually identify the whales by their scars and nicks on their unique dorsal fins and coloration of the area below and behind the fins called the saddlepatch. Researchers can incorporate photos of whales that just about anybody sends them, whether they catch sight of the whales from a boat or just from land—so Samarra encourages that citizen scientists get in touch with a researcher with their photos.

The specific instance with the seal predation opens the door to further important questions, explains Cheshire: Would the whales prefer to eat fish, but they’re turning to larger mammals because there aren’t enough fish around? Have they always been mixing diets?

In the meantime, Samarra hopes that when citizens snap a photo, they realize just how important it could be.

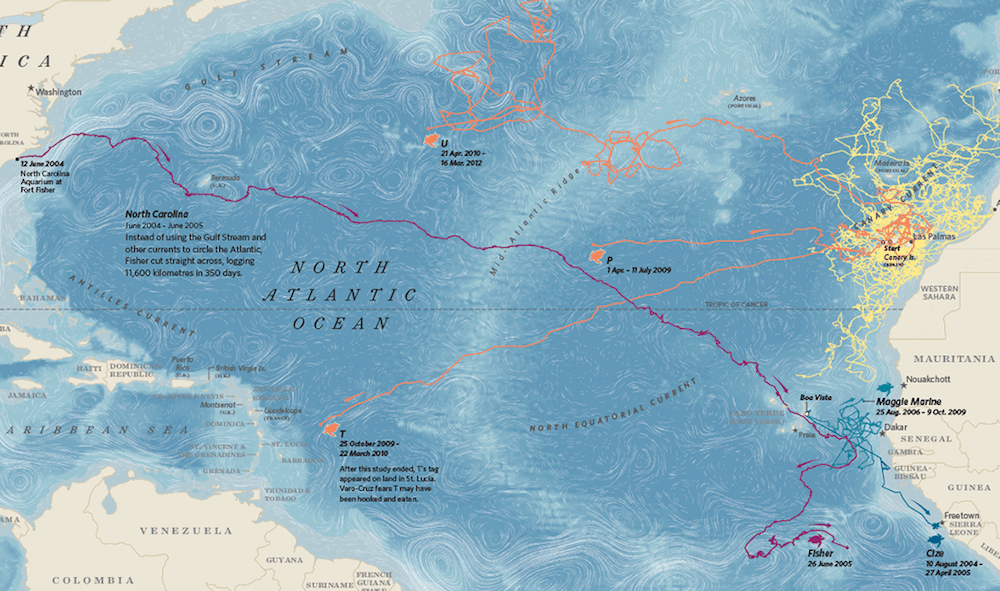

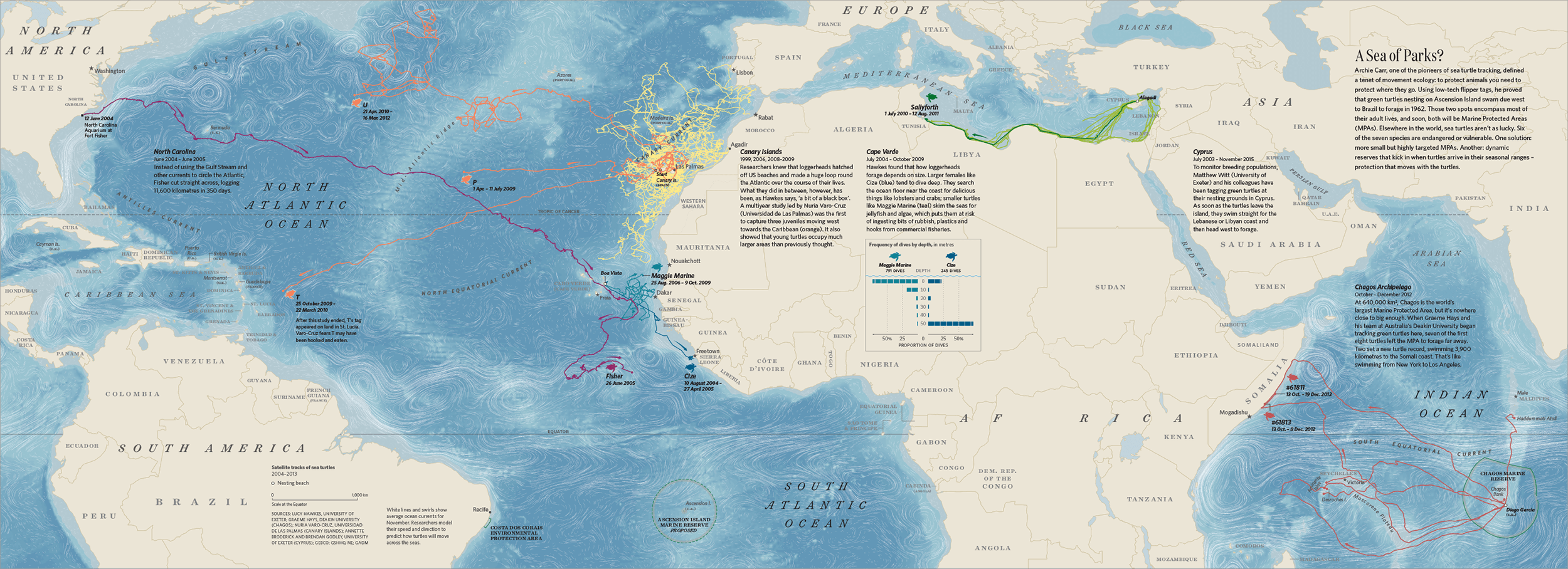

In 1995, a loggerhead turtle named Fisher washed ashore in North Carolina. He was too weak to swim back out to sea solo, so researchers and various institutions cared for him. A decade later, Fisher had grown to a hearty 150 pounds. It was time for him to go.

Researchers generally believe that baby loggerhead turtles born in the western Atlantic hitch a ride via the Gulf Stream to the eastern part of the sea, and hang out there for 10 to 15 years before making their way back to their hometown. It remains a mystery exactly why the turtles return, but Lucy Hawkes, an animal migration researcher and senior lecturer in ecology at University of Exeter, guesses that it’s an evolutionary tendency—the turtles sense that if they themselves were born in a certain place, it must be a safe place for them to have their own babies.

[In a sea of dying coral, researchers have found a possible oasis.]

When Fisher was released, Hawkes expected him to follow that path and allow the Gulf Stream to carry him across the sea. Instead, he bee-lined straight across the ocean towards the eastern Atlantic (as indicated by the purple line on the map above).

“It was like he was playing catch-up in a race,” Hawkes says. “Think of it as a running race around the side of the field. When the race started, Fisher was too busy doing his shoes up or something, and then halfway through the race he thought, ‘Oh god, I better catch up with everybody else!’ and then ran straight across the field rather than around the side of it like everyone else did.”

She had never seen this kind of path before. But Fisher’s case isn’t the only mystery of turtle migration. Hawkes is doing constant sleuthing for migration mysteries: “It’s like being a real-life detective of animals.” She once watched a turtle suddenly reverse course, seemingly without reason, until it wound up in a village; she realized it had been snared by a fisherman. Other times, the culprit isn’t human at all—animals will occasionally eat other animals that are wearing a tracking device.. “You’re kind of like, ‘Do you guys have to do it with the expensive tags on?’” Hawkes laughs. “Eat someone else!’” Furthermore, researchers aren’t sure what mechanism turtles use to self-navigate, or why certain species frequently pass up seemingly ideal foraging locations.

Data may be able to help solve these mysteries. But researchers must always weigh the importance of doing so: “Ethically, we always have these conversations about whether it’s justified,” Hawkes says. A tracking device could either weigh an animal down, or, conversely, create unwanted buoyancy when it tries to dive. It’s up to researchers to decide whether the information they might glean is worth it.

“It’s like we’ve been coloring in this broad picture, and all of a sudden we can zoom in and start to think about some of these details,” says Hawkes.

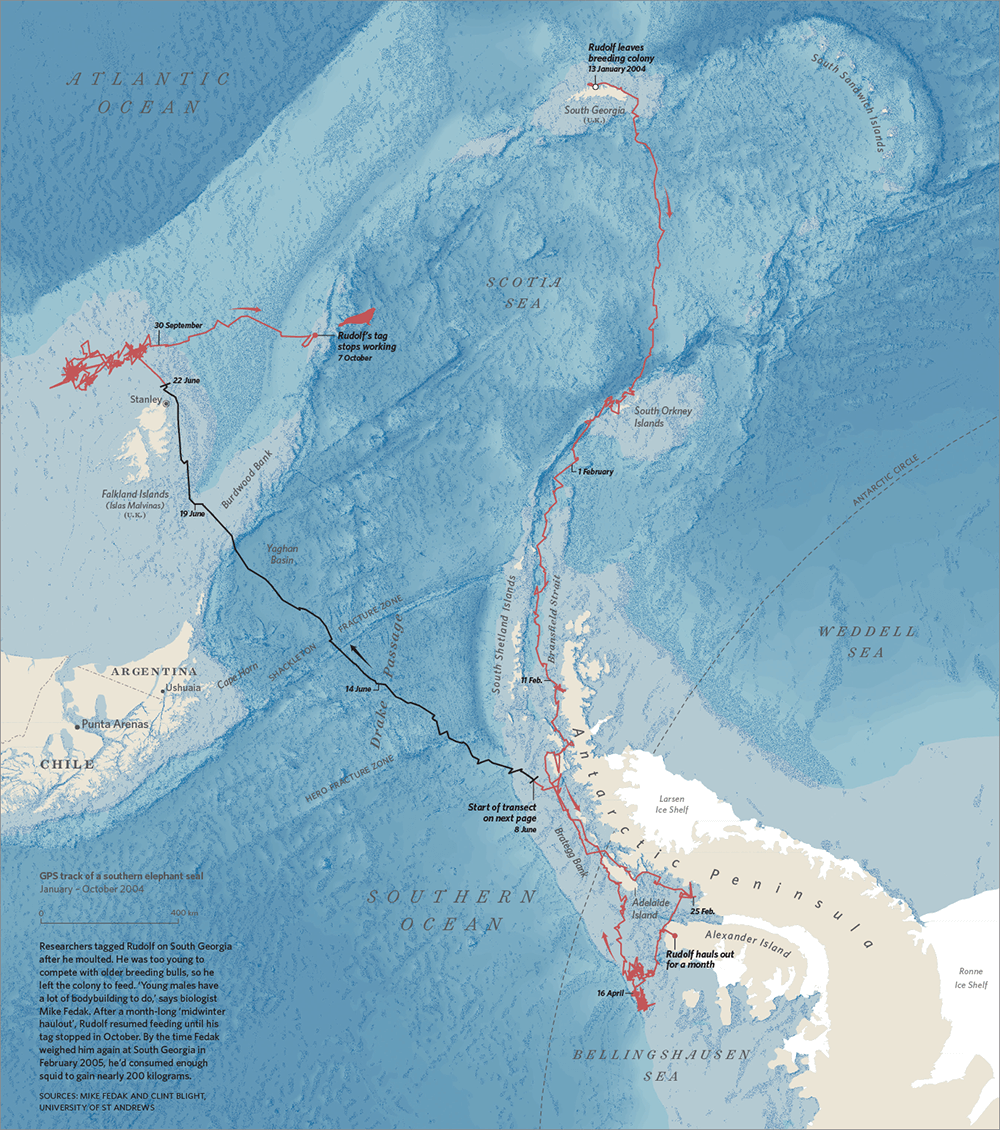

Michael Fedak has been studying seals for nearly 40 years—but these days, he’s getting more information than he bargained for. “When we first started this business, once the animal left the beach, we didn’t know anything,” says Fedak, a seal researcher at the Sea Mammal Research Unit at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

Fedak and his team are able to track a seal’s whereabouts, but they discovered that the conditions of the ocean they’re swimming in pose more of a mystery; oceanographers have very little data for those tough-to-reach areas.

Now Fedak has turned to the seals not just as scientific subjects, but as scouts. He and his team developed a piece of tracking equipment that would measure oceanographic data, such as salinity and temperature—two key factors that oceanographers need to know in order to model how the ocean will behave. The device is glued to the seals’ fur, which they shed once a year during molting, and it transmits the data when the animals surface and the equipment peeks out from under the water. This way, the seals tell the researchers of their behaviors—and also what it is like where they are swimming.

“[This information] provides a sort of spot check on what ocean models might tell us about what the ocean’s like in that particular place,” explains Fedak. “They’re getting the information right there at the time and spot the seal’s operating. From the seal researcher’s point of view, that’s really cool. And from the oceanographer’s point of view, that’s really good because they’re going to places where it’s very difficult to get information from otherwise. That’s a wonderful pairing of those two things.”

However, collecting the data from seals can be a challenge due to the infrequency with which seals surface and create a strong enough signal to transmit the data. Elephant seals, for example, surface 10 percent or less of the time that they’re at sea, explains Fedak, and they’re at sea more or less continuously for months.

How do you distill the complicated life history of an animal into these tiny little packets of a few bits, and have meaning when it gets back here?

“You get this tiny window where they can blat the data out,” Fedak says, and adds, “How do you distill the complicated life history of an animal into these tiny little packets of a few bits, and have meaning when it gets back here?” says Fedak.

And what can those bite-sized chunks of data tell us about the vast expanse of the ocean?

Humans’ relationship with the ocean has evolved over the years, explains Fedak. We’ve gone from thinking that the ocean was completely unknowable, to an infinite resource, to something that can be altered by human behavior, he says. Just as the data that the seals bring back has helped Fedak and his team gain insight, witnessing the paths of marine animal migration across the globe pulls back the curtain on behaviors, patterns, and relationships that would otherwise remain unseen beneath the ocean’s inky waters.

“We fear what we can’t see,” says Where The Animals Go co-author Oliver Uberti. “The ocean is this great unknown, and people have phobias of murky water, their feet dangling down touching crabs and things. And the hope is that data and these tracking technologies allow us to see a little bit of what we can’t see with our eyes.”

All map images reprinted from Where the Animals Go: Tracking Wildlife with Technology in 50 Maps and Graphics by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti. Copyright © 2017 by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Editor’s Note: Language was adjusted to clarify that Oliver Uberti never personally met the elephant named Annie, and to clarify the process of creating the subsequent map.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.