Mama’s Boys, Black Sheep, and Peacekeepers

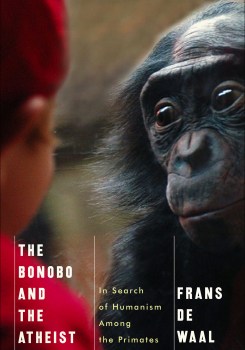

An excerpt from “The Bonobo and the Atheist.”

The following is an exerpt from The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates, by Frans de Waal.

After my lecture in Ghent, fellow scientists took me on an impromptu visit to the world’s oldest zoo collection of bonobos, which started at Antwerp Zoo and is now located in the animal park of Planckendael. Given that bonobos are native to a former Belgian colony, their presence in Planckendael is hardly surprising. Bringing specimens from Africa, dead or alive, was another kind of colonial plunder, but without it we might never have learned of this rare ape. The discovery took place in 1929, in a museum not far from here, when a German anatomist dusted off a small round skull labeled as that of a young chimp, which he recognized as an adult with an unusually small head. He quickly announced a new subspecies. Soon his claim was overshadowed, however, by the even more momentous pronouncement by an American anatomist that we had an entirely new species on our hands, one with a strikingly humanlike anatomy. Bonobos are more gracefully built and have longer legs than any other ape. The species was put in the same genus, Pan, as the chimpanzee. For the rest of their long lives, both scientists illustrated the power of academic rivalry by never agreeing on who had made this historic discovery. I was in the room when the American stood up in the midst of a symposium on bonobos to declare, in a voice quavering with indignation, that he had been “scooped” half a century before.

The German scientist had written in German and the American in English, so guess whose story is most widely cited? Many languages feel the pinch of the rise of English, but I was happily chatting in Dutch, which despite decades abroad still crosses my lips a fraction of a second faster than any other language. While a young bonobo swung on a rope in and out of view, getting our attention by hitting the glass each time he passed, we commented on how much his facial expression resembled human laughter. He was having fun, especially if we jumped back from the window, acting scared. We now find it impossible to imagine that the two Pan species were once mixed up. There is a famous photograph of the American expert Robert Yerkes, with two young apes on his lap, both of whom he considered chimps. This was before the bonobo was known. Yerkes did remark how one of those two apes was far more sensitive and empathic than any other he knew, and perhaps also smarter. Calling him an “anthropoid genius,” he wrote his book Almost Human largely about this “chimpanzee,” not knowing that he was in fact dealing with one of the first live bonobos to have reached the West.

The Planckendael colony shows the difference with chimpanzees right away, because it is led by a female. The biologist Jeroen Stevens told me how the atmosphere in the group had turned more relaxed since their longtime alpha female, who had been a real iron lady, had been sent off to another zoo. She had terrified most other bonobos, especially the males. The new alpha has a nicer character. The exchange of females between zoos is a new and commendable trend that fits the natural bonobo pattern. In the wild, sons stay with their mothers through adulthood, whereas daughters migrate to other places. For years, zoos had been moving males around, thus causing disaster upon disaster, because male bonobos get hammered in the absence of their mom. Those poor males often ended up in isolation in an off-display area of zoos in order to protect their lives. A lot of problems are being avoided by keeping males with their mothers and respecting their bond.

This goes to show that bonobos are no angels of peace. But it also indicates how much the males are “mama’s boys,” something not everyone approves of. Some men feel affronted by matriarchal apes with “wimpy” males. After a lecture in Germany, a famous old professor in my audience barked, “Was ist vrong with those males?!” It is the fate of the bonobo to have burst on the scientific scene at a time when anthropologists and biologists were busy emphasizing violence and warfare, hence scarcely interested in peaceful primate kin. Since no one knew what to do with them, bonobos quickly became the black sheep of the human evolutionary literature. An American anthropologist went so far as to recommend that we simply ignore them, given that they are close to extinction anyway.

Holding a species’ imminent demise against it is extraordinary. Is something the matter with bonobos? Are they ill adapted? Extinction says nothing about initial adaptiveness, though. The dodo was doing fine until sailors landed on Mauritius and found these flightless birds an easy (if repugnant) meal. Similarly, all of our ancestors must have been well adapted at some point, even though none of them is around anymore. Should we stop paying attention to them? But we never stop. The media go crazy each time a minuscule trace of our past is discovered, a reaction encouraged by personalized fossils with names like Lucy and Ardi.

I welcome bonobos precisely because the contrast with chimpanzees enriches our view of human evolution. They show that our lineage is marked not just by male dominance and xenophobia but also by a love of harmony and sensitivity to others. Since evolution occurs through both the male and the female lineage, there is no reason to measure human progress purely by how many battles our men have won against other hominins. Attention to the female side of the story would not hurt, nor would attention to sex. For all we know, we did not conquer other groups, but bred them out of existence through love rather than war. Modern humans carry Neanderthal DNA, and I wouldn’t be surprised if we carry other hominin genes as well. Viewed in this light, the bonobo way doesn’t seem so alien.

Excerpted from The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism among the Primates, by Frans de Waal. Copyright © 2013 by Frans de Waal. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Frans de Waal is the C. H. Candler Professor at Emory University and director of the Living Links Center at the Yerkes Primate Center. De Waal lives in Atlanta, Georgia.