Looking at Light for Signs of Dark Matter

This honeycomb-like array is helping scientists on their search for dark matter.

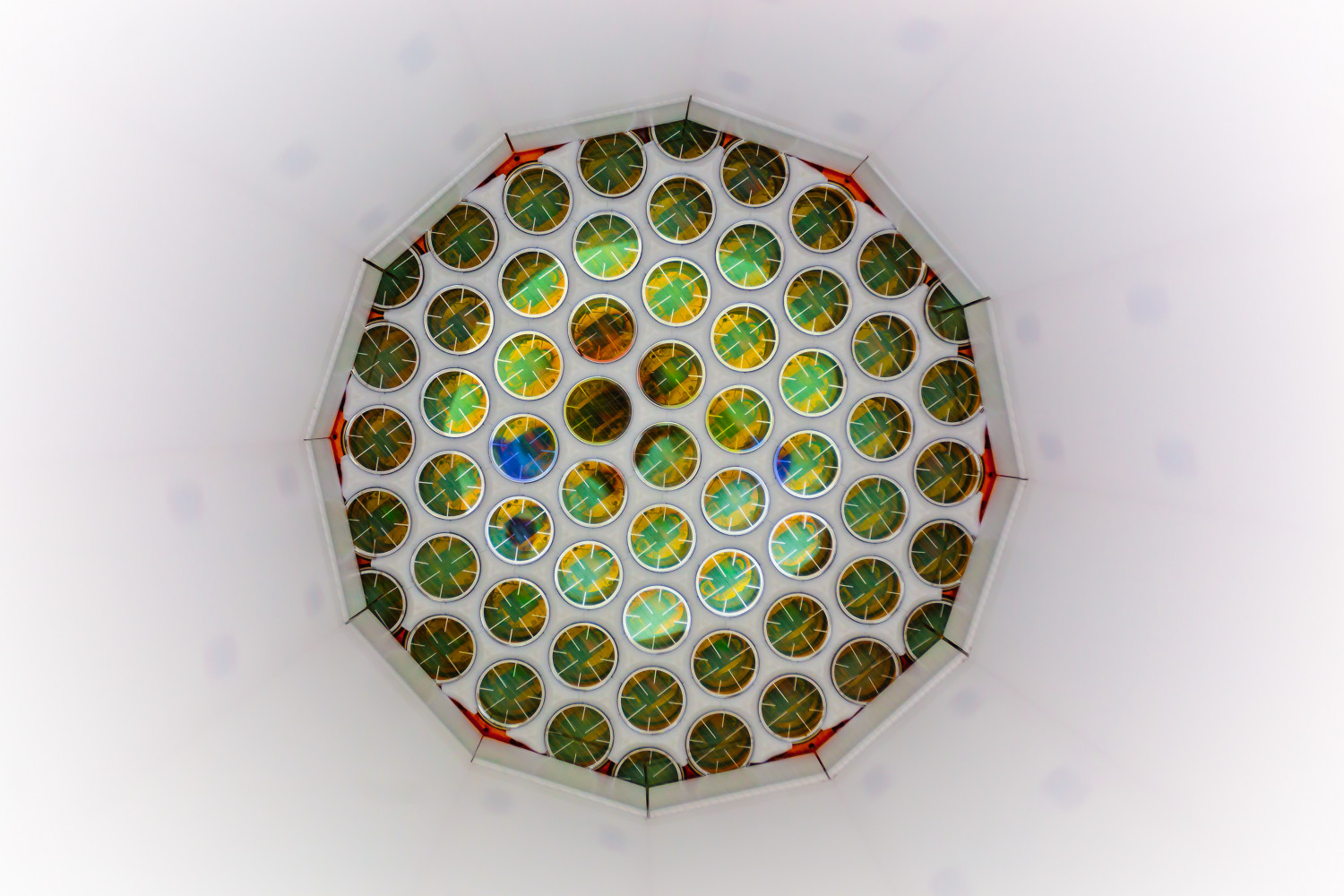

LUX’s photomultiplier tubes arranged in a hexagonal pattern inside the particle detector. Photo by Matt Kapust of Sanford Underground Research Facility

A mile underground in Black Hills, South Dakota, this honeycomb-like structure is playing a major role in the hunt for dark matter.

Each circle holds a photomultiplier tube, or PMT, which is a vacuum tube capable of detecting low levels of light. In this case, the PMTs are being used in a particle detector to spot interactions between liquid xenon and a type of dark matter called a “weakly interacting massive particle,” or WIMP, says Rick Gaitskell, a Brown University physics professor currently working in Black Hills on the Large Underground Xenon (LUX) experiment, a collaboration of more than 100 scientists to detect dark matter. (Watch the video below for more on LUX.)

WIMPs are one of the most popular candidates for dark matter. Theoretically, they interact with one another and with other matter gravitationally. But they also might interact through what’s called weak force, an attractive force that, while still weak, is stronger than gravity at very short ranges on the subatomic level. It’s this type of interaction that the LUX experiment is looking for in its detector.

The idea is that if a slew of particles interact with xenon through the weak force, the various masses of those particles can be determined through a series of calculations based on the energy given off during each interaction. And once researchers know the mass of a particle, they can determine its identity. In this case, the researchers at LUX are looking specifically for the particles that match the mass they’ve calculated to be dark matter.

The LUX detector—also called a time-projection chamber—holds 700-plus pounds of liquid xenon. The liquified noble gas is a scintillator, so when a particle of some sort interacts with a particle of xenon, light is produced. The PMTs (there are 122 of them lining the top and bottom of the detector, secured in copper mounting arrays) are so sensitive that they can pick up single photons of light.

Photomultiplier tubes operate “a little bit like a television working backwards,” explains Gaitskell. With televisions, old-fashioned cathode ray tubes would take electronic signals and convert that into a stream of electrons. The electrons would hit the front face of the television and emit light, he says.

Conversely, PMTs have photocathode material at their front faces that collect light and convert those photons into electrons, which hit dynodes inside the tube that multiply them.

The photomultiplier tube “allows you to amplify what initially is a single electron into a cascade of over a million electrons,” Gaitskell says. Those electrons become “a small pulse of voltage,” albeit one big enough for LUX researchers to read as data on their computers. In that data, they’re searching for a signature that corresponds to what they think is the mass of a WIMP.

The scientists are still struggling to understand how often dark matter particles interact with the liquid xenon. They initially estimated that a kilogram of xenon would get hundreds of interactions with WIMPs a day. They soon figured out the calculation is more like one interaction every 100 years.

Dark matter “involves particle physics at an energy scale that’s at or beyond anything that we’ve achieved so far,” says Gaitskell. “And as a consequence, we’re still not quite sure what the strengths of this physics, these particles [i.e., WIMPs and xenon nuclei or atoms] are.”

When the LUX researchers ran the detector for three months in 2013, they recorded nearly 100 million interactions, or events. They narrowed those down to just 160 that seemed to fit their calculations for dark matter. “But crucially, none of those events passed one of our tests for dark matter,” Gaitskell says.

They’ve now been running LUX for almost a year, and are hoping to get 300 days’ worth of interactions before shutting it off in mid-2016 to analyze the data.

“If we see something, we will only have seen a small number of events,” Gaitskell says. “If we don’t see anything, either way, we have to build a bigger detector.” The next detector, dubbed LUX ZEPLIN (LZ), will scale up the LUX experiment by a factor of 20—meaning more than eight tons of liquid xenon, and bigger and more sensitive PMTs.

Chau Tu is an associate editor at Slate Plus. She was formerly Science Friday’s story producer/reporter.