Latina Space Scientists Want To Stop Being The Exception

Three leaders in space science from Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Argentina on battling sexism and innovating in their fields.

Katherinne Herrera-Jordan (top left), Sandra Cauffman (right) and Clara O'Farrell (bottom left). Credit: Idalia Candelas

This story was produced by Science Friday and América Futura as part of our “Astronomy: Made in Latin America” newsletter and series. It is available in Spanish here.

Sally Ride went down in history, not only for being the first American female astronaut, but for also starring in one of NASA’s most embarrassing moments. Yes, the tampon incident. She was the one that NASA suggested take 100 tampons for a 6-day space mission in 1983. (That’s far too many.) But menstruation was something utterly foreign to the country’s most prestigious scientists. Up until then, few knew that zero gravity wouldn’t increase women’s bleeding. Even fewer thought women could explore space. So why fit them with suits, much less talk about periods?

This anecdote is a reminder to many female engineers and space scientists that no organization is immune to machismo, and that not long ago, women were hardly paid any attention—even less so if you were Latina. The memories are still fresh in the minds of Katherinne Herrera-Jordan, Sandra Cauffman, and Clara O’Farrell, three Latin American women who dreamed of going to space as children, and whose studies have contributed to understanding it a little better.

Although the path seems to have cleared a bit for women, they say impostor syndrome never goes away, and that they continue being mansplained things they already know. That’s why when Herrera-Jordan is asked how much she thinks women are celebrated in space, she sarcastically answers, “Just as little as on Earth.” But feminism is also making progress, and all three women agree that they leave behind a less hostile environment for those who follow, and that today’s astronauts can talk to the press about actual spaceflight instead of how they do their hair, as happened to Russian Yelena Serova.

Katherinne Herrera-Jordan didn’t even know she liked science until she discovered that physics and chemistry could solve the big questions she pondered as a little girl. As a child, her parents would turn to scientific articles and the television series “MythBusters” to answer them. Now she seeks answers to her questions—of which there are still many—in the lab. The first opportunity to do so was for an undergrad biochemistry and microbiology project. Her goal was ambitious: to understand how certain microorganisms behave in space. The resources she had for this? “None,” laughs the 26-year-old Guatemalan.

Teaming up with Dr. Luis Zea, a renowned aerospace engineer from Guatemala, and Fredy España, a fellow mechatronics engineering student, Herrera-Jordan set out to create her own microgravity simulator. These devices are used to expose laboratory samples to conditions similar to those in space, and typically cost around $30,000. Three months and $31 later, they had succeeded—their little contraption made from recycled household appliances paid off.

“I never thought of getting rich on this, but I started to market them at more affordable prices (between $500 and $5,000) because they were designed so that everyone could do science,” says Herrera-Jordan, who founded Verne Technologies. “It doesn’t feel right that Latin Americans don’t have the same access to the space industry. These tools allow us to perform research from here, not just from the United States.”

Thanks to the equipment she developed, Herrera-Jordan supports research like a project developed by the Guatemalan Association of Engineering and Space Sciences related to the seeds she grew up eating: beans. She has already discovered that if tepary beans (Phaseolus acutifolius) were grown in space, they would germinate faster and absorb more nutrients. Now she wonders what all can be done with them: Maybe they could alleviate child malnutrition in her country, feed astronauts, or even be planted on the moon. “Many organizations are designing technology for people to live there one day,” she says. “Hopefully, the little Guatemalan beans will make it there, too.”

It’s impossible to sum up Sandra Cauffman’s life’s work. Over the nearly 40 years she’s been working for NASA, she’s been in almost every role—since starting as a contractor “putting glasses” on the Hubble Space Telescope in 1991 after a flaw was discovered in its mirror, to today, serving as deputy director of the astrophysics division in the Science Mission Directorate. However, this 62-year-old Costa Rican remembers perfectly well every step it took to get to her current role, in which she manages a $1.5 billion budget. “My job has always been to understand what scientists want and build it,” she says.

Cauffman acknowledges that female leadership is a challenge in such a male-dominated industry. “Several male colleagues have told me they were more qualified than me. It wasn’t easy to stomach, but I learned that they were the ones with the problem,” she says. That’s why she tries to “leave the door open” for those who come next. “We have to make sure there are girls who follow in our footsteps and see that it can be done. Space is for us, too, and we have a lot to bring to the table.”

The MAVEN mission is among her most cherished memories. It was the first time a NASA probe went to Mars to measure its upper atmosphere and analyze what led to the loss of volatile compounds such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, and water. This was an expedition to understand how climate change happened on the red planet. Their conclusions are clear: “Earth is our lifeboat. Although there are more than 10,000 exoplanets, on no other can we live as we do here,” Cauffman says.

Dr. Clara O’Farrell spent four years studying the behavior and movement of jellyfish in the ocean, thinking about creating autonomous robots that would collect underwater information. She never thought that this knowledge could be used to build supersonic parachutes to land on Mars. But when she got the call from NASA, she said yes without a second thought. Without realizing it, she brought together her two greatest passions: marine biology and space engineering, two fields that have more in common than you might think.

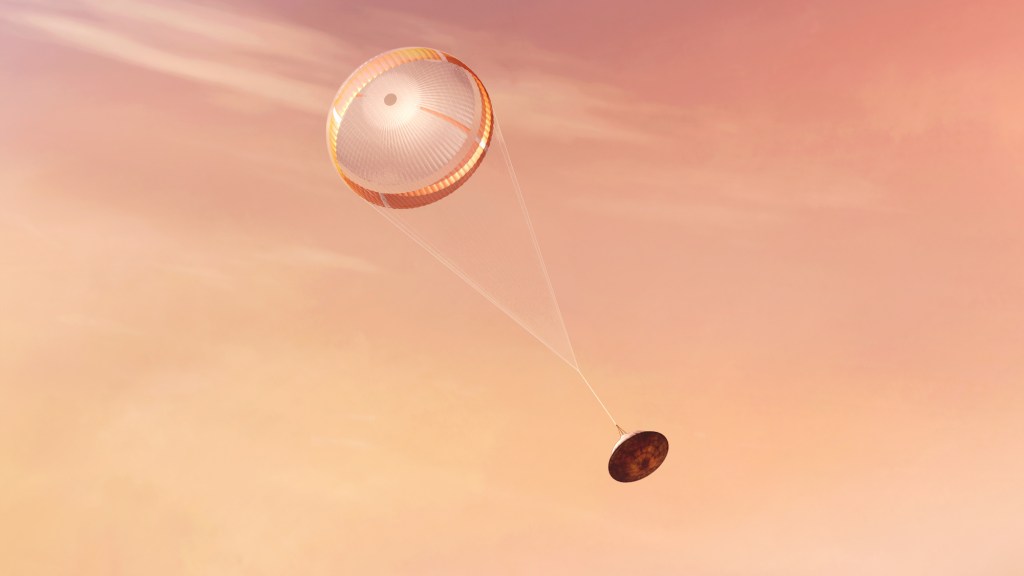

For nearly two decades, space science has looked to plants and animals to learn from their movements and tissues: propellers that mimic bird wings, equipment that optimizes space by drawing inspiration from insect brains. Through bioengineering, 38-year-old Clara O’Farrell managed to shape the largest and strongest supersonic parachute ever created by NASA, in the mission that sought to determine whether there was life on Mars. The 70-foot-wide parachute deployed after the Perseverance rover blazed into Mars’ atmosphere at almost twice the speed of sound on February 18, 2021. And the rover soon turned up answers. “We found organic compounds mixed with some very particular minerals that indicate that at some point there was life,” O’Farrell says.

And, as expected, when one question was answered, more came up: What was it like? Was it like ours? “That’s our next mission, and it will be the most complicated one we’ve done,” she says. From the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, she continues to develop new parachutes that are bigger and stronger. “If you want to bring back samples from Mars or do crewed missions, we’ll need to land heavier things. There’s a lot of work to be done,” she says excitedly.

O’Farrell feels a responsibility to draw more girls and young women to the opportunities opening up in the field. “The numbers suggest that what happened to me was highly unusual—I’m the exception. And that has to stop.”

This story was translated from Spanish by Laura González.

Noor Mahtani is a reporter for América Futura at El País. She is based in Bogotá, Colombia.