Insect Microfossils Provide Prehistoric Insights

Discovered at La Brea Tar Pits, the pupa helps reveal clues to what the environment was like in Southern California during the Pleistocene Epoch.

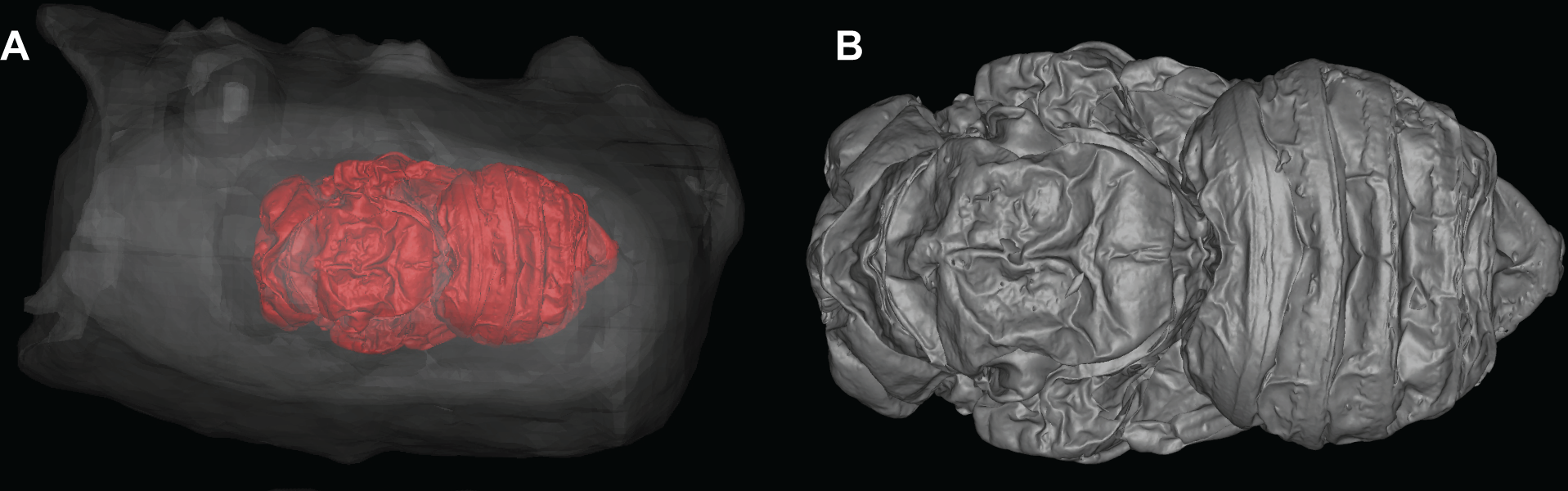

Micro CT scans of (A) a dorsal view of a male leafcutter bee pupa within its nest cell, and (B) a dorsal view of the pupa. Images by Justin Hall, Dinosaur Hall, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Los Angeles’ La Brea Tar Pits are probably best known for their collection of large fossils of saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and Columbian mammoths. But lately, scientists have been focusing on the area’s microfossils (a loose term to describe the remains of organisms including insects, birds, and mollusks that are best studied and identified with a microscope). Turns out, these smaller specimens can reveal a wealth of information about prehistoric climate and habitats.

A prime example entails two fossilized insect pupae from a species of leafcutter bee called Megachile gentilis. The specimens are about 35,000 years old and signify the first record of this particular species from the Pleistocene Epoch, according to John Harris, chief curator of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and the Page Museum at La Brea Tar Pits (hear his SciFri interview here). Researchers described the fossils in PLOS One this past spring.

Scientists first discovered the fossils as one intact specimen in 1970, about 200 centimeters deep in a fossil deposit called Pit 91, says Harris. They thought it was a fossil bud and added it to the collection at the Page Museum. “And nobody thought much more about it until about a year ago, when we had a young researcher [Anna R. Holden] who was interested in fossil insects,” Harris says. “Looking through the collection, she came across this particular specimen and realized it wasn’t a bud or a gall.”

In fact, the “bud” turned out to be two very well preserved structures called nest cells, each containing a leafcutter bee pupa—one male, one female. (Leafcutter bees lay a single egg in a nest cell, which develops into a larva and finally an adult bee that chews its way out.) So far, these are the only fossilized leafcutter bee pupae that have been recovered in a three-dimensional state and not squashed flat like most fossils of soft-bodied animals, according to Harris.

Using micro CT scans to analyze the anatomy of the pupae and the construction of the nest cells—which leafcutter bees build from plant material—Holden and her team identified the species as M. gentilis, which still exists today, says Harris. The picture above shows CT scans of the male pupa.

“Different species of leafcutter bees construct their nest cells in different ways—some of them have sort of rounded ends, some have flat ends,” Harris explains. “They use different shapes of leaves and they construct in different fashions, so it should be possible to tell the species apart just by looking at their nests.”

These particular fossilized nest cells were constructed from the leaves of at least four different types of woody trees, shrubs, or vines, indicating that the habitat at the time was either woodland or riparian. This observation, along with what we know about the modern distribution of M. gentilis, suggests that the climate at the tar pits was cooler and more humid than its current arid and dry state, according to Harris.

Microfossils like these provide better hints about the prehistoric environment than fossils of larger species because those bigger animals traveled farther distances and might have simply died near the tar pits, whereas organisms such as insects, rodents, and snails mostly likely spent their whole lives in the vicinity, says Harris.

The excavations of microfossils from Pit 91 alone have doubled the number of species identified in the Tar Pits so far, from 300 to more than 600. Harris estimates that it could take another decade before the pit is fully excavated, alongside some 16 other fossil deposits newly recovered in the area.

Watch the video below to learn how scientists use paleoforensics to recount the grim details of animal deaths at La Brea Tar Pits.

Chau Tu is an associate editor at Slate Plus. She was formerly Science Friday’s story producer/reporter.