How To Survive The Anthropocene

A new collection of essays curated by environmentalist James Lovelock aims to help people better understand the earth.

From "The Earth and I," by James Lovelock, et al. Illustration by Jack Hudson/Courtesy of TASCHEN

If widespread disaster befell the Earth, what would you need to know to survive? What could you learn from mankind’s accomplishments and failures?

These were questions James Lovelock had in mind when he wrote an essay for Science magazine in 1998 titled “A Book for All Seasons.” The scientist, environmentalist, and originator of the Gaia hypothesis envisioned a guide that could help survivors of a catastrophic event better understand planet Earth and how it works.

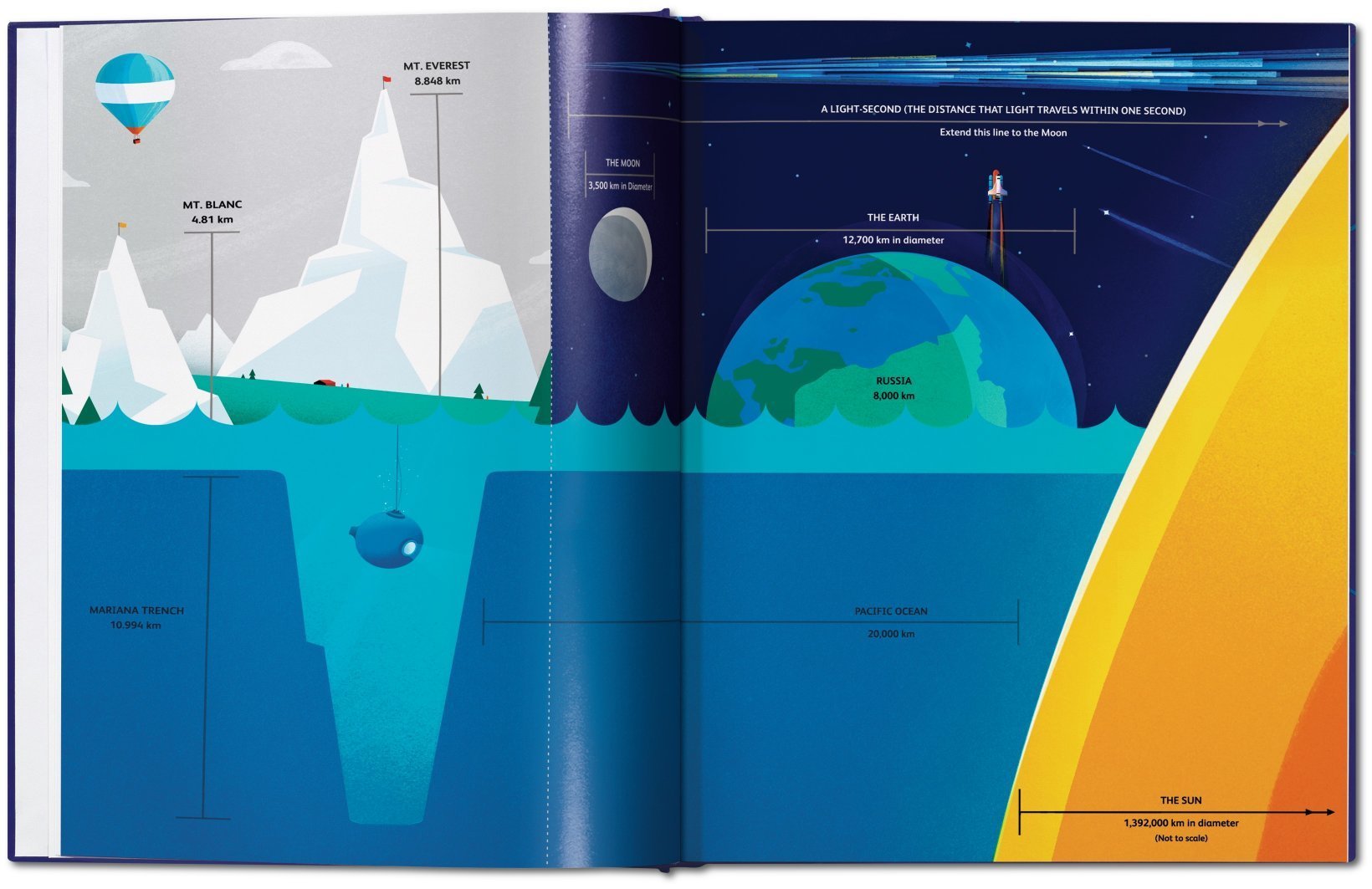

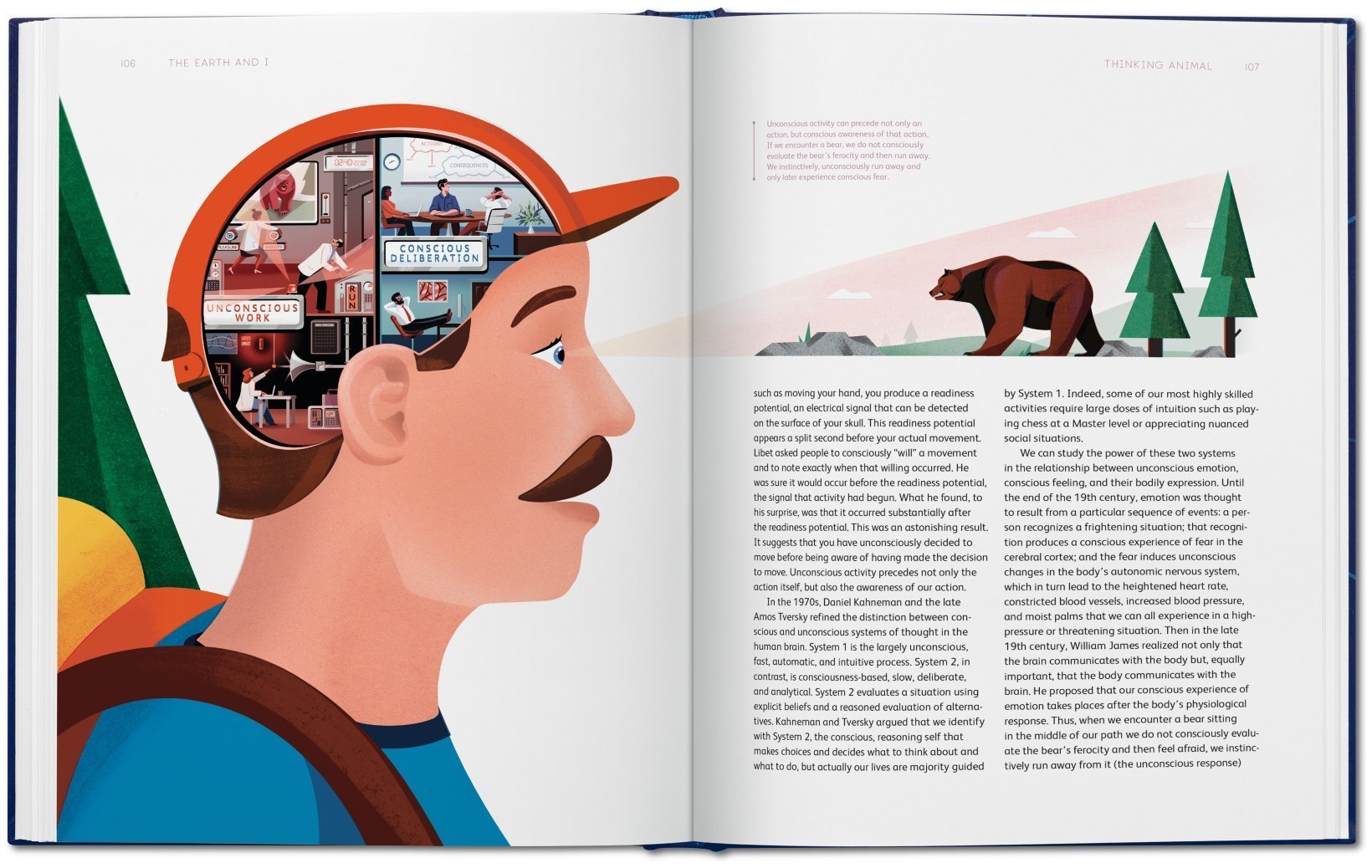

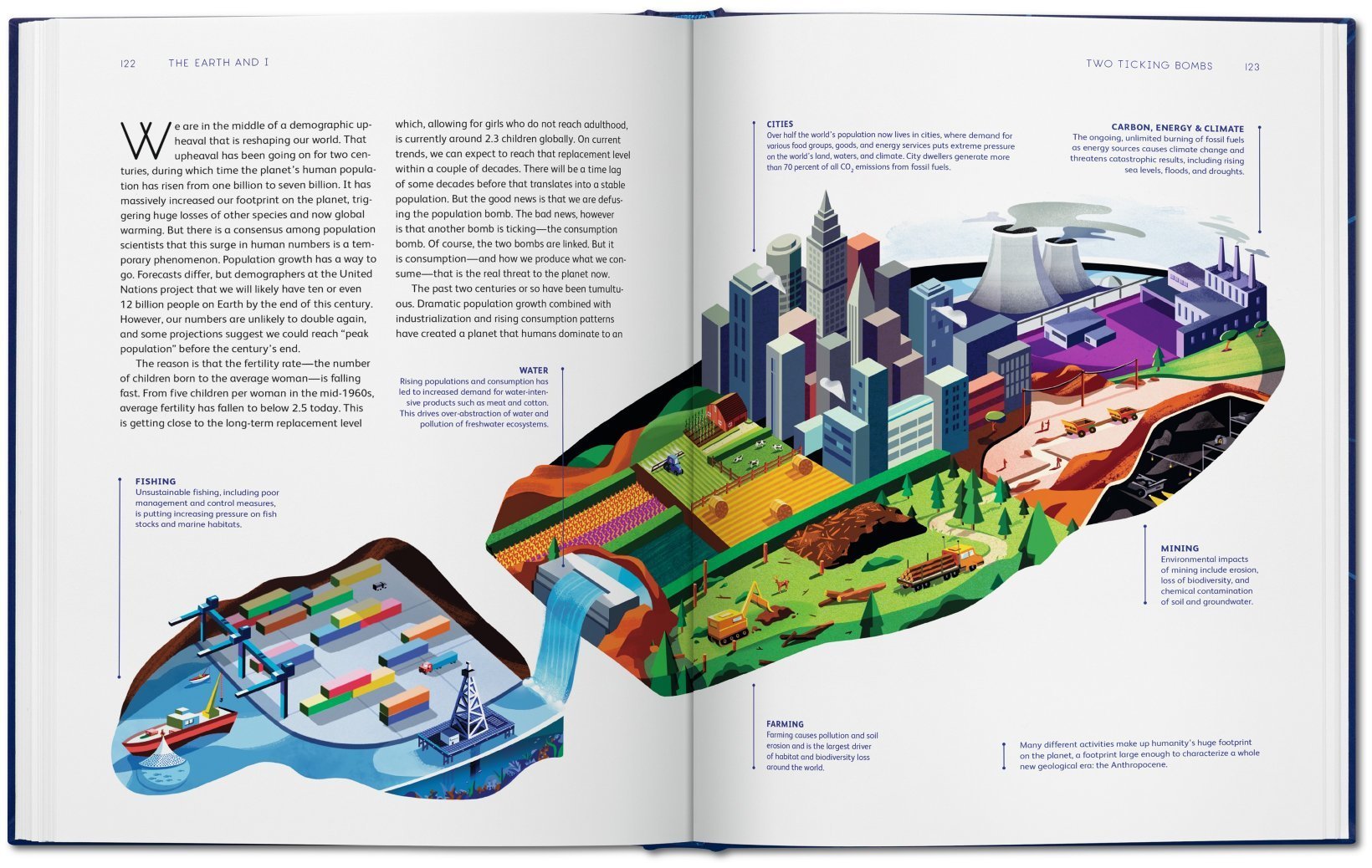

Eighteen years later, a version of that guide has materialized as The Earth and I (TASCHEN Books, 2016), a collection of essays by scientific thought leaders—including theoretical particle physicist Lisa Randall, biologist E.O. Wilson, and neuropsychiatrist Eric Kandel—and curated by Lovelock. The book provides insight into the intricacies of Earth and humanity, covering everything from the planet’s geology and fossil records to how tools have evolved into today’s technology. Whimsical illustrations and infographics by British artist Jack Hudson illuminate concepts described in the text.

“We are buried beneath mountains of fast accumulating data,” Lovelock writes in the introduction. “Rather than adding to the data load, this book aims to offer real understanding.” Together the essays act as a sort of primer to the Anthropocene, what some scientists consider a new geological epoch marking mankind’s profound influence on the planet. The book’s overarching theme is examining how we got to where we are, and what the future holds.

Science Friday recently chatted with Lovelock about how the collection came together, whether his Gaia hypothesis has changed over time, and if he’s optimistic for the future of the planet amid recent and vast environmental changes.

You’ve essentially been working on this book since you wrote that Science essay in 1998. How did it arrive at its current form, The Earth and I?

Science had asked me to write an article about what to do in the way of survival, if there were some big disaster, from any cause, some time in the future. What I said in my article was, wouldn’t it be wonderful if, in every home around the world, there were something rather similar to the Bible? When I was a kid, there was a Bible in every home, and people would talk about it as a ‘good book’ and refer to it for all sorts of things. And I felt that now that we were getting much more ecumenical, there was a need for a [secular] good book in every home that told them what to do if bad things happened—if there was really a worldwide disaster of some kind.

The book would include fundamental bits of science without going into the complex details of how we discovered them. Things like, for example, disease is not spread by some witch chanting up on a hill; it’s spread by bacteria and viruses. Basic information of all kinds, like how to light a fire if you’re stranded in a woody wintertime.

I knew that I couldn’t write such a book; it would require a writer with the qualities of the old Bible writers. But I wondered about it, and then [in 2012,] Marlene [Taschen, the business director at TASCHEN Books] took up the idea. We tried to find as many present-day thoughtful people and writers who could contribute a first try at such a book. And that is what this is.

Do you have a favorite essay from the book?

One of the first writers in the book is Martin Rees, our present Astronomer Royal, the chief astronomer in the nation [the U.K.]. [Rees’ essay discusses the origin and evolution of the cosmos and Earth.] I’ve always found him a very wise man and a very thoughtful one, and I thought his ideas would be quite good as representing astronomy and cosmology, so that people could understand the stars and the seasons a little bit better.

The book is more or less a primer on the Anthropocene and mankind’s lasting influence on Earth. There was recent news that scientists have suggested the Anthropocene began around 1950. What do you think about this?

I don’t wholly agree with them because I think they’ve taken into account the science of it, but they haven’t taken into account the economics. You see, there were many people throughout history who took energy and turned it into useful work—right back to the time of the ancient Greeks, 2,000-plus years ago. But what counts in the modern world, and what really led to the Anthropocene, was when steam engines were first invented and started being produced commercially.

But there’ll be arguments for a long, long time to come about which was the first event that caused it, I reckon. I think when it exactly started is not all that important, any more than it’s important when we were born.

You formulated the Gaia hypothesis, which is the idea that Earth is a self-regulating system, back in the 1960s. With all the environmental change that seems to be occurring rapidly across the globe, do you think Earth will self-regulate and ‘correct’ itself in some way?

I think what everybody tends to forget with the planet is that its sense of time is much, much longer than ours. It’s existed for nearly four billion years, and it slowly regulates. It isn’t something that happens at the speed that we react as humans. This is the main thing that is not thought about or noticed. I mean, we can make a desperate change to the Earth, but you can’t expect the planet to respond immediately, on our terms. [EDITOR’S NOTE: Lovelock elaborated on that “desperate change” in a follow-up email as “the huge quantity of CO2 that we have added to the atmosphere.” He writes, “The short-term response of the Earth system (Gaia) is a rise in temperature of about 1°C. The long-term response is measured in thousands of years and involves the ocean and the biosphere. It will takes a long time for the effects of the CO2 addition to go away, even if we stop now.”]

For example, a friend of mine and I had a paper in Nature quite a long time ago about the lifespan of the biosphere, and we saw a crucial moment occurring around about 100 million years from now. Well, that’s an awful long time in human time, but it’s a very short time in terms of the lifespan of the planet.

Has the Gaia theory changed for you since you formulated it?

No, it hasn’t. It came into my mind quite suddenly in America at Jet Propulsion Lab in 1965. Well, that’s over 50 years ago, and it’s been argued about an amazing amount. But it hasn’t changed. It stays the same.

Have the reactions to the theory changed at all?

A little bit. They were quite rough in the early days [laughs]. People tended to treat it as New Age nonsense, not to be taken seriously. But time’s gone on, they’re a little bit more kindly towards it, maybe because I’m growing quite ancient—I’m 97—and they feel it would be bad to treat me roughly [laughs].

Do you feel optimistic about the future of Earth?

I’m pretty optimistic about humans. I think we’re a pretty special animal in many ways. We’re the first ones to have taken energy from the sun and used it to process information on a grand scale—nothing before us did that. So I think in many ways, we’re nearly as important as a species as were the photosynthesizers who, 3.7 billion years ago, learnt to use the energy of the sun to produce food and oxygen.

Do you think there’s anything we as humans could be doing to help better Earth now?

I wouldn’t dare to say [laughs].

*This article was updated on September 29, 2016, to include an Editor’s Note containing an additional response from James Lovelock. It pertains to the “desperate change” that he says humans are making to Earth.

Chau Tu is an associate editor at Slate Plus. She was formerly Science Friday’s story producer/reporter.