How To Have A Dinner Party In Space

Astronaut Leland Melvin recounts daily life aboard the International Space Station, including a communal dinner, celebrating a birthday, and the challenges of trying to sleep in microgravity.

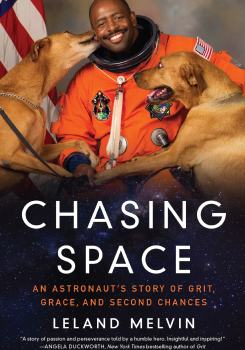

The following is an excerpt from Chasing Space: An Astronaut’s Story of Grit, Grace, and Second Chances, by Leland Melvin.

There are so many unforgettable aspects of life in space, including the experiments, the robotics, and the spacewalks, but I think my most memorable moment took place when Peggy and her crew invited us to have dinner over in the service module. “You guys bring the vegetables, we’ll bring the meat,” they said, and we all congregated around the small table, with some floating above and others below. There we were, French, German, Russian, Asian American, African American, listening to Sade’s silky vocals and having a meal in space. Out the window we could see Afghanistan, Iraq, and other troubled spots. Two hundred and forty miles above those strife-torn places, we sat in peace with people we once counted among our nation’s enemies, bound by a common commitment to explore space for the benefit of all humanity. It was one of the most inspiring moments of my life.

While the space smorgasbord with Peggy’s crew included Russian and international cuisine along with canned beef and barley, most of our meals consisted solely of typical American fare. Many people associate astronaut food with that freeze-dried ice cream sold in museum gift shops. In truth, you won’t find that on the space station, but you will find thermally stabilized and irradiated food that tastes much like the entrees served on Earth. Some food needed only to be heated while others required the addition of water. My favorites included beef brisket, mac and cheese, and string beans with almonds. M&M’s and Raisinettes made great snacks, with the added bonus of being fun to play with. We trapped the tiny treats in water bubbles and gobbled them up as they floated by.

Staying properly nourished and fit was critical to our success at performing the jobs we had to do. The effects of zero gravity on the body made self-maintenance part of our daily routine. Without the pressure of Earth’s gravity, the body begins to do funky things. For example, every vertebra gets room to move, stretching the spine. I’m five foot eleven on Earth but I was six feet on the station. After my spine elongated, when I went to bed on the first night I felt some pains in my lower back. I had to curl up in an attempt to alleviate the discomfort. The heart also changes in space. Its gets smaller and changes shape because it doesn’t have to pump as hard to pull the blood up from your feet. Without gravity, our bones change shape, lose calcium, and become more brittle. As a preventive measure, we worked out on a treadmill specially designed to help us combat loss of bone density. (We also had an exercise bike and a resistive exercise device or weightlifting machine.) Some astronauts experience intracranial pressure changes that push on their eyeballs, changing the shape of the eyeballs and forcing the astronauts to wear glasses in space. We kept different prescriptions of glasses on board just in case someone’s vision changed.

Meanwhile, our major objective was to install the Columbus Laboratory. It began with a spacewalk. Before passing through an airlock and a hatch to enter the vacuum of space, Rex and Stan put on suits with bulky backpacks that on Earth would weigh about 300 pounds. Their equipment included oxygen, heating, cooling, carbon dioxide removal systems, and a computer. Once in space, Stan attached a grapple fixture that enabled me to grab and move Columbus with the fifty-eight-foot robotic arm. Working with Dan and Leo at the robotics workstation, I could look at monitors to maneuver the big shiny module. It was very slow work that required a lot of configuration to line it up just right. We had beautiful views of the Earth through the aft window as we pulled Columbus into its berth in Node 2. Following the installation, we had outfitting tasks to do, including removing launch locks and installing handrails. Our second and third spacewalks involved more work with the Columbus, including attaching external payloads. I operated the arm for those procedures and others, such as switching out a nitrogen tank on the space station and retrieving a broken gyroscope for repair and reuse.

[How do astronauts stay healthy in space?]

When we weren’t busy moving and installing payloads for the space station, we’d take in the light shows. For example, when we were over the Earth’s southern hemisphere we’d see this green glow of particles hitting the atmosphere. The colors were different over the northern hemisphere—purple, yellow, and blue. I had been told about the cosmic rays that would pass through the vehicle and hit my optic nerves, making me think I was seeing flashes of light, even though that was not really happening. The flashes were like sunbursts of different colors popping in my eyes and in my head.

Sleeping brought a different kind of light show. It was a pretty incredible experience because we didn’t have the sensation of lying down; we floated inside our sleeping bags as we dozed. We slept amid a whole din of pumps and motors, so many whirring around us; the noise made it seem like we were in a factory. On top of all that, my dreams were so vivid from the stimulus of the day. Behind my closed lids, I saw blues, greens, whites, whether they came from the ocean, whether they came from the sun, or whether they came from flashes in my head from these high-energy particles. The colors intertwined with my dream state and I sometimes saw alien forms and green clusters of light moving and dancing in a way that made me think of little green men on Mars. At one point in the mission, a huge, inside-out cheeseburger, dripping with grease, began to float through my dreams. I was just chomping on this burger, a juicy contrast to the irradiated food I had been consuming in real life.

[Astronauts are allowed to bring one item with them into space. Don Pettit chose candy corn.]

There was no birthday cake on the shuttle either, but that didn’t stop me from celebrating my own big day. It happened when a surprise party organized by the Astronaut Family Support Office brought my parents, sister, and a host of friends to a conference room at NASA Langley. Through a video hookup I saw all their beaming faces, surrounded by blue balloons and noisemakers, as they gathered around a cake. My parents wore gray sweatshirts with “Atlantis” emblazoned across the front. I had just finished a long, challenging day operating the arm, and seeing their faces made me happier than they could have realized.

“A lot of prayers are going up to you,” my dad told me.

“A lot of prayers are coming down to you,” I replied.

The “party” ended with the whole group serenading me. Rudy King, a coworker at NASA Langley who often played basketball with me, blew out the candle.

“This is really special, guys,” I said. “If I cried, the tears would just float away. I’ll save those tears for when I get home.”

Five days later, our mission was completed. It was time to return to Earth. In the history of human spaceflight, there had only been a little more than five hundred people who had been given an opportunity to go off-planet, and I had been one of them.

Excerpted from Chasing Space: An Astronaut’s Story of Grit, Grace, and Second Chances. Copyright 2017 by Leland Melvin. Published with permission from Amistad Press and HarperCollins Publishers

Leland Melvin is a former NASA astronaut and the author of Chasing Space: An Astronaut’s Story of Grit, Grace, and Second Chances (Amistad, 2017). He’s based in Lynchburg, Virginia.