How To Draw Dinos For A Living

According to dinosaur drawer Gabriel Ugueto, it’s a great time to be a paleoartist.

When Gabriel Ugueto was growing up in Caracas, he was “obsessed” with a book: A Guide to the Birds of Venezuela. When he cracked open the book’s spine, hundreds of detailed illustrations of the colorful, native birds seemingly flew off the pages. Ugueto loved animals, he loved drawing, and he loved drawing animals, and he told himself that one day, he would create a guide like this one—except for lizards and other reptiles, his “main love.” “Every time I grabbed a lizard,” Ugueto says, “I used to draw it.”

While he hasn’t yet written the Guide to the Reptiles of Venezuela, Ugueto does draw animals for a living. But the animals he depicts are usually much bigger than the lizards he would find in the garden. Ugueto is a paleoartist and scientific illustrator, which means that he studies fossilized clues in order to piece together portraits of prehistoric animals that have gone extinct. The reanimated creatures he depicts go on to live in books, museums, TV documentaries, and scientific journals.

To become a paleoartist, “You have to know your subjects very well,” Ugueto says. “Look at your cat or your dog or your bird closely everyday. Go out to the park. See animals, see animals, see animals. And read, read, read, read. And practice, practice, practice, practice.”

The road to becoming a paleoartist isn’t always straightforward, though. Ugueto didn’t always know that this was what he wanted to do; he dabbled in studying biology, but ultimately decided to formally pursue illustration and graphic design in university, after which he moved from Venezuela to Miami, Florida. But he kept reading. Ugueto continued to work as an independent researcher, working with co-authors who were associated with herpetology museums and institutions, and he even described several new lizard species from Venezuela. When it came to describing a new species in these papers, many of the scientists he worked with ran into the same roadblock.

I would say, ‘No problem. I can draw it.’

“Many of my co-authors were telling me, ‘We don’t have a picture or a photo of this species because it’s so rare,’” says Ugueto by phone. “And I would say, ‘No problem. I can draw it.”

Eventually, enough people were asking for commissions that Ugueto transitioned into working full-time as a freelance paleoartist and scientific illustrator.

These days, when he receives an assignment, Ugueto begins by closely examining fossils. He measures them to get a sense of the animal’s proportions, and, if he can’t handle the actual fossils and is working off photographs, he will ask the paleontologist to describe the texture of the bone in certain places, as this can occasionally shed light on what will appear on the outside. Then, he dives into his research, starting with the available scientific literature about the animal in question, as well as its close relatives.

For one assignment, Ugueto was tasked with reconstructing a series of birds from the Cenozoic era. “Let’s say that I just have a thigh bone,” he says. “A lot of those birds are just known from one bone, a thigh bone. I have to basically reconstruct the rest of the animal…based on what animals it is closely related to.” And of course, these reconstructions don’t simply live on a blank page—Ugueto also dives into additional reading to research the environment that these animals lived in.

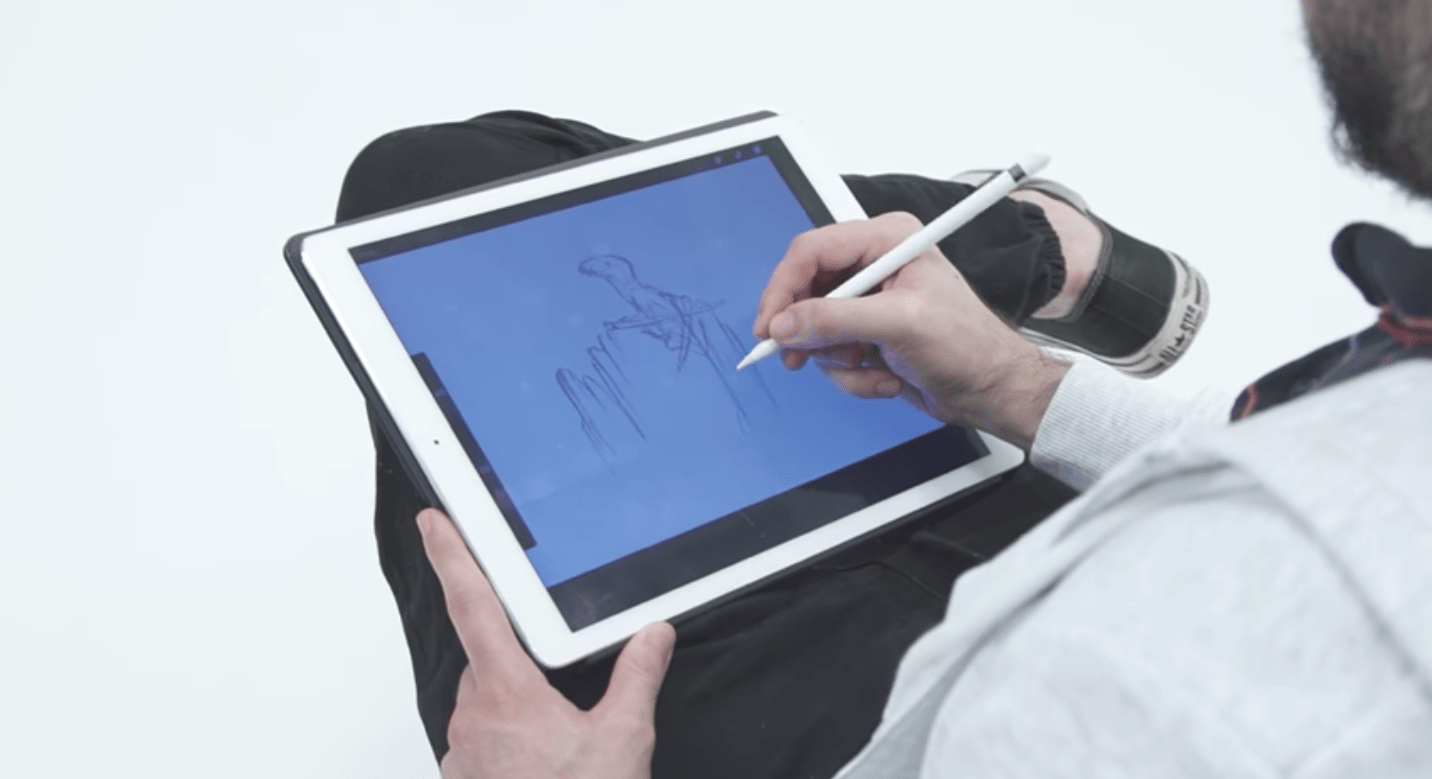

After a lot of reading and researching, Ugueto finally begins to sketch. Once he and the paleontologist or commissioner have settled on a rough outline of the piece, he literally fleshes out the project—beginning with a full skeletal reconstruction, then piecing together how each muscle will attach to each bone, and, finally, how the external features like scales and feathers will attach to the muscles. It’s all in the name of visual accuracy, which Ugueto describes as his “golden rule.”

But for paleoartists working in the 19th and early 20th centuries, such extensive research wasn’t necessary, or even possible.

“It was really a creative free-for-all,” says Zoë Lescaze, art historian and author of Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past. “In one image, an iguanodon might look like a sort of benign, scaly rhino, and in the next, a bloodthirsty, murderous, grotesque dragon.” Those dragon-like iguanodons were no coincidence. In fact, early paleoartists often tapped into historical traditions of monster-making, explains Lescaze.

And while the tools that paleoartists use, like fossils and the knowledge of paleontologists, haven’t changed too drastically over the years, early paleoartists “lacked the visual library that any paleoartist—or any nine-year-old—now has when you say the word ‘dinosaur,’” says Lescaze. That “visual library” took decades to build as paleontologists learned more, and as a result paleoart went through a number of different “revolutions,” as Ugueto put it. In the 1940s and ‘50s, dinosaurs were generally depicted as slow-witted, lumbering, lowly swamp-dwellers, and a wave of new research in the 1970s transformed them into lithe, nimble creatures that are closer to how we know them today.

“Now, I feel like we’re in another revolution,” says Ugueto. “There are a lot of recent discoveries and science is allowing us to look at dinosaurs in a whole different way. We know now what coloration they could have had. We know a lot more about the way they were related to each other. We know now more than ever about how they could have behaved, who they are related to. Every year, so many new species get discovered and described. So there is a huge, huge amount of work waiting to be depicted in illustration right now.”

But the monster-like depictions of dinosaurs have endured, and Jurassic Park-like representations in pop culture have so profoundly shaped how people envision prehistoric animals that not everyone reacts positively to the more accurate versions that Ugueto depicts.

“You have no idea…T. rex is the one that usually gets people riled up,” Ugueto laughs. The Tyrannosaurus rex is now known to have sported a smattering of feathers, and not everyone considers that an “awesome” look. “They want monsters for movies, not real animals,” Ugueto says.

Perhaps the T. rex may not have looked as “awesome” as originally depicted by early paleoartists. But Ugueto argues that what we lose in “awesomeness,” we gain back in other ways. When we accurately resurrect these creatures, he says, “you get to see them as a real animal. You get to see them as something that you can understand how it behaved, how it moved, how it ate, how it breathed. You can feel it. In a lot of ways, even if it’s a strange-looking animal, you can see it as more familiar to you.”

And when accuracy is the goal, and we learn to understand these long-lost creatures better through it, some may say that’s pretty “awesome” too.

[You asked your canine cognition curiosities and a neuroscientist answered.]

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.