Househunting For Honey Bees

How do bees figure out where to put their next hive? As we learn in this excerpt from “The Lives of Bees” by Thomas D. Seeley, it requires a bit of househunting.

The following is an excerpt from The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild by Thomas D. Seeley.

The honey bee’s process of choosing a dwelling place unfolds during colony reproduction (swarming), which occurs mainly in late spring and early summer (May–July) in the Ithaca area. The first step in this house-hunting process begins even before a swarm has left the parent nest. A few hundred of a colony’s oldest bees, its foragers, cease collecting food and turn instead to scouting for new living quarters. This requires a radical switch in behavior. These bees no longer visit brightly lit, sweet-scented sources of nectar and pollen; instead they investigate dark places – knotholes, cracks in tree limbs, gaps among roots, and crevices in rocks—always seeking a snug cavity suitable for housing a honey bee colony.

The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild

Upon discovering a potential homesite, a scout spends nearly an hour examining it closely. Her inspection consists of a few dozen trips inside the cavity, each one lasting about one minute, alternating with trips outside. While outside, the scout scurries over the nest structure around the entrance opening and performs slow, hovering flights all around the nest site, apparently conducting a detailed visual inspection of the structure and surrounding objects. While inside, the bee scrambles over the interior surfaces, at first not venturing far inside the cavity, but with increasing experience pressing deeper and deeper into the remote corners of the hollow. When her examination is complete, the scout will have walked some 50 meters (about 150 feet) or more inside the cavity and so will have crossed all its inner surfaces. Experiments that I conducted with a cylindrical nest box whose walls could be rotated freely while its bright entrance opening remained stationary—so, in effect, the scout stepped onto a treadmill when she went inside the nest box—have shown that a scout bee judges a potential nest cavity’s volume by sensing the amount of walking required to circumnavigate it. Exactly how a scout bee judges a cavity’s roominess using the information gained from the walking (and occasional flying) movements that she makes inside the cavity remains a mystery.

The long duration of the nest-site inspections made by scout bees suggested that they assess multiple properties of a site to judge its suitability. Moreover, the regularities in certain nest-site properties that Roger Morse and I had found—in entrance area, entrance height, cavity volume, and so forth—supported the idea that bees have strong preferences in their housing. It was also possible, however, that the consistencies we found merely reflected what was generally available in tree cavities. At this point, I turned to surveying the scientific and beekeeping literature for information about the nest-site preferences of honey bees, but I found almost nothing, just one article in a French beekeeping magazine on how to build attractive bait hives for catching wild swarms. This situation surprised me, because I knew that beekeepers had worked for centuries to design the perfect hive, and I figured they might have looked to the natural living quarters of honey bee colonies for guidance, but evidently they had not. At the same time, finding this gap in our knowledge delighted me, for I realized then that my curiosity about the bees’ natural homes had drawn me to a region of uncharted territory in the biology of Apis mellifera.

The method I developed for asking the bees about their nest-site preferences was simple: set out nest boxes that differed in certain properties and see which ones were occupied preferentially by wild swarms. More specifically, I set out nest boxes in groups of two, three, or four, with the boxes in each group identical except for one property, such as entrance area or cavity volume. The boxes within each group were spaced about 10 meters (33 feet) apart on similar-size trees (or a pair of power-line poles) where they were matched in their visibility, wind exposure, and location. Each group of boxes served to test one (potential) nest-site preference, and it did so by giving swarms a choice between one box whose properties all matched those of a typical nest site in nature (e.g., average entrance size, average cavity volume, etc.) and another box (or boxes) identical to the first box except in one property (e.g., entrance size), the value of which was atypical. In this way, wild swarms were tested for a preference in the one variable in which the boxes differed. For example, to test whether the distribution of entrance areas reflects a preference for small entrance openings, I set up pairs of cubical nest boxes that were identical except that one box had an entrance area of 12.5 square centimeters (ca. 2 square inches), which was typical, and the other box had a large entrance area of 75 square centimeters (ca. 12 square inches, the size found in a Langstroth hive), which was atypical.

Planning this investigation was easy, but executing it was hard. Altogether, I built 252 nest boxes in the winter of 1975–1976, and I deployed them in small groups over the countryside around Ithaca in the summers of 1976 and 1977. Luckily, wild swarms were plentiful, so the experimental plan worked. My nest boxes attracted 124 swarms, enough to reveal many of the bees’ secrets about what they seek in a homesite.

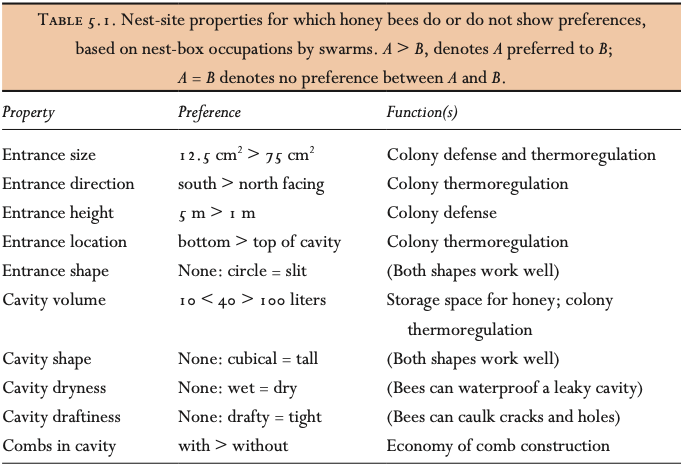

Table 5.1 summarizes the results of this study. We see that the bees in these wild swarms revealed preferences in four aspects of the entrance openings of their nest cavities. This was not surprising, given that this passageway is the interface between the colony and the rest of the world. All of a colony’s food, water, resin, and fresh air comes in through this opening; all its waste and debris goes out of it; and all attacks by predators will focus on this point of greatest vulnerability. We also see that the wild swarms expressed preferences about just two features of the cavity itself: its volume and whether it was furnished with beeswax combs (from a previous colony).

Thomas Seeley is a professor of biology at Cornell University, and is author of Following the Wild Bees: The Craft and Science of Bee Hunting. He lives in Ithaca, New York.