How Sexual Intercourse Was Invented, 385 Million Years Ago

Okay, but how exactly did sex come about? Science journalist Rachel Feltman dives into the saucy science of doing it.

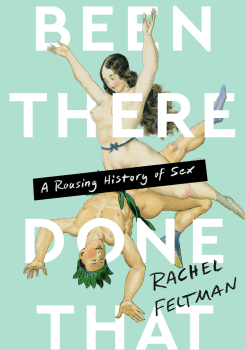

The following is an excerpt from Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex by Rachel Feltman.

Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex

Where amorous bonefish from the ancient world give us a glimpse at the early days of boot-knockin’. Here are five lessons I hope to have taught you by the end of this book:

We’re going to get into all of this and a whole hell of a lot more to boot. But before we can talk about chastity belts, the surprising number of secret sex museums in European history, giraffes peeing on each other in a horny way, and mail-order radium suppositories, we need to answer one teeny-tiny question: What is sex, anyway? And to answer that query, we need to go back a couple billion years.

There was a time before sex. When the earth was new, all living things reproduced asexually: rather than finding sexual partners, individuals begot copies of themselves to perpetuate their ilk. This was simple. It was efficient. Every member of the species was capable of reproducing and did so without help from any of their kin. Life boiled down to eating, avoiding being eaten, and occasionally copy-pasting your DNA by splitting yourself in two. Some prokaryotes learned to swap DNA with one another on the fly, which helped their species adapt and combine genetics in new ways. But their offspring were still the result of whatever genes progenitors had handy at the time—not of a dalliance with another individual.

Sometime around one to two billion years ago, as best as the fossil record can tell us, the first eukaryotic organism decided to muck about and make things a lot messier. This common ancestor, likely a single-celled protist, maintained the ability to clone its own cells—in a way, we’re all reproducing asexually every time we make new cells within us, which translates to nearly four billion births a second per person—but it also started making sex cells, or gametes. (To complicate matters, some researchers argue that this last eukaryotic common ancestor, or LECA for short, was actually not a single cell containing all the genetic traits necessary to make a eukaryote, but rather a population of diverse single-celled organisms that swapped just the right genes at just the right time to make all the proteins it takes to build a defined cellular nucleus. Luckily for us and for the length of this book, we don’t need to know which scenario is correct in order to know that eukaryotes… happened.) Unlike the so-called diploid cells that each contain the entirety of an organism’s genetic code, gametes are haploid, which means they only carry half. They need to combine with other haploid cells to create a fully functional set of chromosomes.

Bangiomorpha pubescens, so named as the first known occurrence of “sexual maturity” for life on earth, is currently considered to be the oldest fossilized organism that certainly had these abilities. The specimens in question are thought to be just over a billion years old, making them the most ancient fossilized critters that appear to be single, complex organisms—as opposed to colonies of unicellular bacteria.

Unlike those of earlier organisms, Bangiomorpha pubescens spores show three distinct morphologies, representing cells it could have used to reproduce asexually, but also “male” and “female” cells similar to those used for sexual reproduction in modern Bangio algae. It seems likely now that all extant eukaryotes, or organisms with cells divided into membrane-bound organelles, have sex in their ancestral history—even the few that reproduce exclusively asexually today. They may have come from lineages that dabbled in both modes of procreation, then reverted (sort of like how whales and dolphins descend from animals that emerged from the sea, evolved into mammals, and then scooted their way back into the ocean for reasons unknown).

But this wasn’t quite sex as we know it. Plants reproduce sexually by trading pollen on the breeze. Our first sexually reproducing ancestors likely just oozed up against one another at the cellular level. When did we start, you know, doing it?

Our oldest evidence of penetrative intercourse is about 385 million years old and comes in the form of fossilized remains of the way too aptly named Microbrachius dicki. I know. I know! But believe it or not, M. dicki got its rather pointed moniker from Scottish baker-turned-botanist Robert Dick in the nineteenth century. Mr. Dick would never know that the ancient armored fish he chiseled free from rock were sexual revolutionaries. Not until 2014 did a study confirm that the remains showed the earliest known example of internal fertilization and copulation. And oh, did that reveal some glamorous origins for getting it on: M. dicki’s eight-centimeter-long body included a “bony L-shaped genital limb” called a clasper, which males used to transfer sperm to females. Not to be outdone, the species’ better half developed “small paired bones to lock the male organs in place.”

But the first known instance of sex as we know it still wasn’t really sex as we know it. Based on the placement of those bony, interlocking claspers, paleontologists say the frisky fish probably swam side by side to do the deed. “With their arms interlocked,” one of the lead study authors said in 2014, “these fish looked more like they are square dancing the do-se-do rather than mating.” I can’t speak for everyone, but I’d say we’ve come a long way. And our journey from square dancing in the sea to engaging in the thrilling array of activities we now call sex is full of shocking, disturbing, and hilarious twists and turns. M. dicki is just the world’s introduction to intercourse; once humans hit the scene, we really learned to have fun with it.

But enough about how sex came to be. Why did we start having it? The answer may not be as straightforward as you think.

Excerpted from Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex by Rachel Feltman. Copyright 2022. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Rachel Feltman is a freelance science communicator who hosts “The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week” for Popular Science, where she served as Executive Editor until 2022. She’s also the host of Scientific American’s show “Science Quickly.” Her debut book Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex is on sale now.