The History Of Ice Skates

From bones to blades, they just don’t make ice skates like they used to.

Long before we watched Nathan Chen land quadruple jumps on Olympic ice, humans were ice skating simply to get around.

Federico Formenti, a physiologist and sport scientist at King’s College London, worked with a team to reconstruct four historical models of ice skates—from approximately 1800 BCE through the 18th century—and tested the metabolic cost of each of skate compared to a modern day skate. Meanwhile, Dustin Bruening and a team at the University of Delaware built the ice skate of the future—a skate that could prevent injuries and potentially lead to higher jumps and more spins that skaters have yet to stick in competition, like the quintuple jump.

But there were some major changes between the bone skates that Formenti worked with and the ultra-flexible skates that Bruening and the team developed. The shape and size morphed, as did the reasons people wore them.

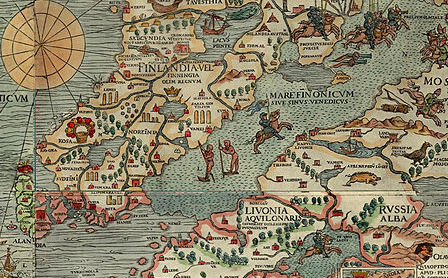

Let’s skate through history, shall we? First, look closely at this 1539 map of Scandinavia below. Can you find the first known depiction of ice skaters?

Here they are!

These skaters look nothing like the ones gliding across glassy ice at the Olympics. They’re chugging along on skates constructed from horse and cow bones, the oldest of which date to approximately 1800 BCE. Developed in Scandinavia, the earliest skaters pierced a hole through the bone and fitted them with leather straps. But they weren’t trying to nail the quadruple jump; the bones skates were an efficient means of transport along the many rivers and canals that run through the region.

Unlike today’s skates, the bone skates had no sharp edge, and were flat and slippery on the bottom. That meant that, unlike what we do today, skaters couldn’t push with their legs—instead, they stabbed a stick into the ground between their legs to push themselves along. This made turns particularly challenging, as skaters had to slow down and push sideways with the stick. But once they pushed off, it was smooth skating. In addition to being durable, Formenti explains, bones were naturally one of the best materials for skates because they contain fat. The oily nature of the surface in contact with the ice reduces the coefficient of friction and allows them to glide more effortlessly across the surface. “It’s fun, because you wouldn’t expect to move so smoothly and so quickly in a straight line without moving your legs,” says Formenti. “It’s entirely different from using metal blades.”

[When you hear music, do you see blue?]

In the 13th century, skaters made no bones about discarding the old model and constructing their skates from wood with an iron blade fastened underneath. This meant that they had far more control over their movements, and could ditch those cumbersome sticks and propel themselves using their legs. But it also meant that the blades didn’t glide as smoothly—the change from iron to bone meant there was an increased coefficient of friction with the ice. Still, by the 14th century, iron blade skates supplanted bone skates in places like the Netherlands.

As skate makers glided into the 15th century, they added a dramatic curled toe to the blade. Formenti suggests there are a few reasons for it: First, the anatomical shape of the bones used in the original iteration of the skates had a natural (though far less pronounced) curve, and it’s possible early skaters were used to it. The curl also prevents the tip of the skate from getting stuck in the ice and causing its wearer to trip. A third reason for that characteristic curl? “I presume that it was also a matter of fashion,” says Formenti. “I’m not sure the height and shape of the curl beyond, say, the first centimeter has a functional role.”

[Meet the women who made the internet.]

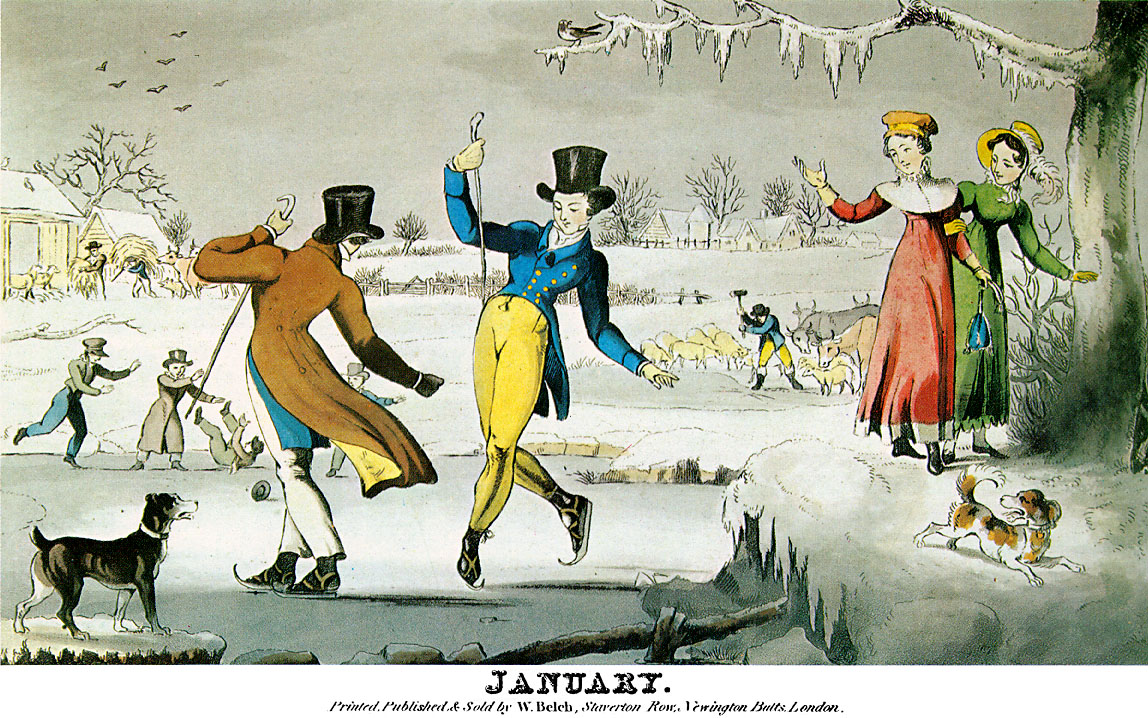

Until the 18th century, ice skating was simply ice skating. But the Little Ice Age, which started around the 13th century and continued into the 19th, led to a period of particularly cold winters, and newly cheap, mass-produced ice skates, which launched the wintertime ice-travaganza into popularity. The activity soon became more specialized—and so did the equipment.

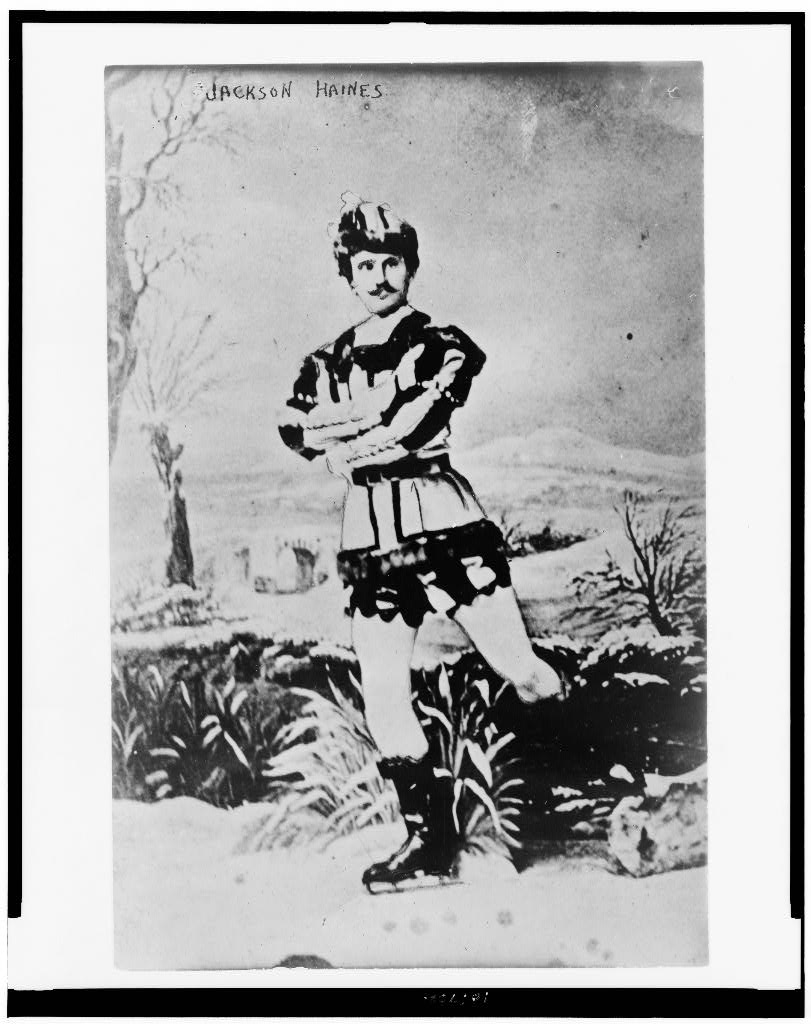

In 1772, Englishman Robert Jones penned A Treatise on Skating, which is considered the first account of figure skating by Encyclopedia Britannica, marking a split between what would become speed and figure skating. Near the end of the 19th century the American ballet dancer Jackson Haines adapted his techniques for ice dancing, and is widely considered the father of figure skating. The 20th century brought the toe pick, the jagged edge on the front of the figure skate that enables skaters to push off of the ice for jumps.

Meanwhile, skate makers also began to construct skating blades as long and thin as possible for speed and transportation. Why? When it comes to speed skates, blade length matters. A skater’s weight is distributed over the given surface area of a blade, and when that blade is short, the weight is all concentrated in one spot. But when it’s long, the weight is distributed more evenly, and the blade won’t sink as deeply into the ice. That results in a smoother glide.

In the 20th century, skates became what we know today. Old strap-on skates gave way to boots with screwed-in blades, allowing skaters to move more easily and safely, and also take fewer strides over a distance. In addition, the blades of these skates are twice as long as those of the 13th century, but improvements in technology and materials have allowed for lighter and more efficient skates.

“For the same metabolic power, nowadays skaters can achieve speeds four times higher than their ancestors could,” writes Formenti in the 2007 study—and he estimates that that difference is even greater now, with subsequent developments in skating technology like the clap skate, which has a hinge that allows the heel to detach from the blade and allow for more natural movement.

“In that sense, I wonder whether the optimal length for ice skating [blades] has been reached,” he muses, “but obviously there’s a limit to how long [the blade] can get and still be easily controlled.”

Researchers are still pondering the future of the figure skate. In 2004, a team at the University of Delaware developed a figure skating boot with a hinged ankle, which was originally designed with injury prevention in mind. Biomechanics experts estimate that when figure skaters land those jumps, they hit the ice with a force five to eight times their body weight. When they land with a rigid ankle, they’re absorbing that force over a very short period of time.

“So we wanted to give them an ankle back,” says Dustin Bruening of Brigham Young University, who worked on the project at Delaware. The hinged ankle allows skaters to dissipate that force over a longer period of time and a greater range of motion.

The hinge may lead to another unintended advantage: potentially higher jumps. When a skater is able to use their ankles and move through a wider range of motion as they push off the ice, they’d hypothetically be able to jump higher. And a higher jump means more time in the air—which presents the opportunity for more rotations, perhaps unlocking the door to the much-anticipated quintuple jump.

Figure skaters have been slow to adopt the hinged boot. For one thing, when it comes to figure skating, appearance matters, and the hinged boot is slightly bulkier than traditional boots. Plus, a company would need to invest in and manufacture the boot (the skate was only briefly manufactured by one company).

But if you build them, will the skaters come?

“It’s quite a drastic change to suddenly have a lot of freedom of ankle movement,” says Bruening. “The skaters were practicing their entire lives in a certain pair of boots, and then you ask them to change their boots, it’s a very different feel for them. I think a lot of skaters didn’t want to adapt, couldn’t adapt, felt awkward in them. There was probably a big learning curve.”

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.