Why Hawaii Is The Perfect Place For Rainbows

From sacred symbols to colorful displays of physics, local experts in Hawaii seek to understand the natural wonders of rainbows.

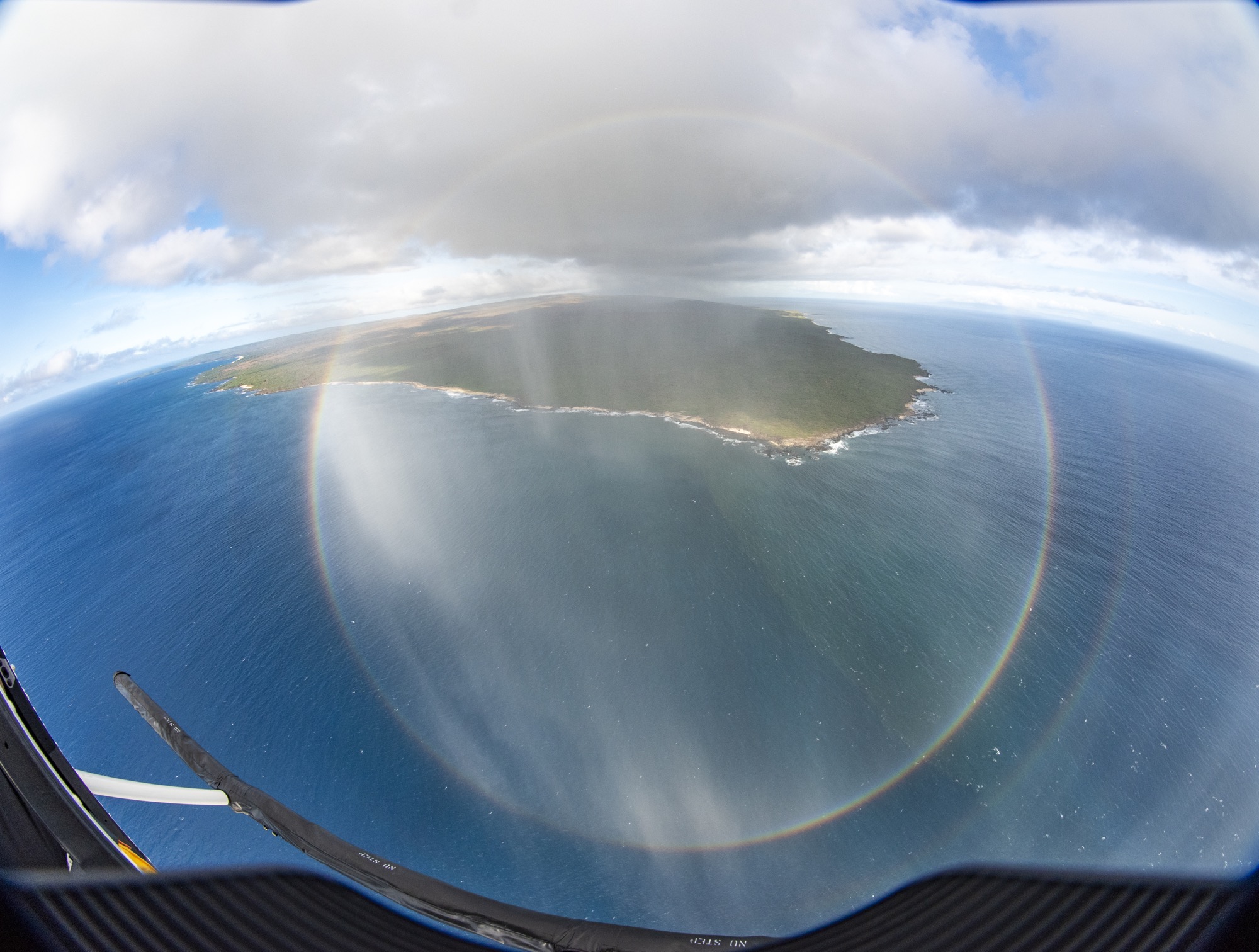

From a helicopter, you can see a circle rainbow with Molokai Island in the background. Credit: Steven Businger

When you see a rainbow, you’re only viewing a small slice of the picture. That signature multicolored curve stretching across the sky is not actually a “bow” at all, but a circle partially tucked under the horizon. Soaring above the Hawaiian Islands, Steven Businger has been lucky enough to see a rainbow in its completion: a 360-degree loop of color.

“There are rainbows happening all the time all around the Earth, but a lot of these rainbows we can’t see,” says Steven Businger, an atmospheric scientist and professor in the University of Hawaii Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. “The angle is such that the rainbow is actually below the horizon. That’s why in Hawaii, it’s fun to go up in a small plane or helicopter and shoot the rainbows from the air.”

That bird’s eye view is just one of many observations Businger has made to better understand the physics, geometry, and optics behind these natural wonders. Businger is a rainbow chaser—he’s flown in helicopters, hiked up misty volcanic peaks, and run out of his home in the middle of breakfast to photograph a double rainbow. These fantastic beams of color are atmospheric optical effects, explains Businger, which he describes in a recent paper published in the journal Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

“I have had a fascination with atmospheric optics since I was a kid and rainbows are a jaw-dropping, beautiful phenomenon,” he says. “For many people, it really captures their attention.”

Rainbow over Oahu. Credit: Steven Businger

The recipe for a rainbow is quite simple, says Businger: On a basic level, “you need some sunshine and you need some rain.”

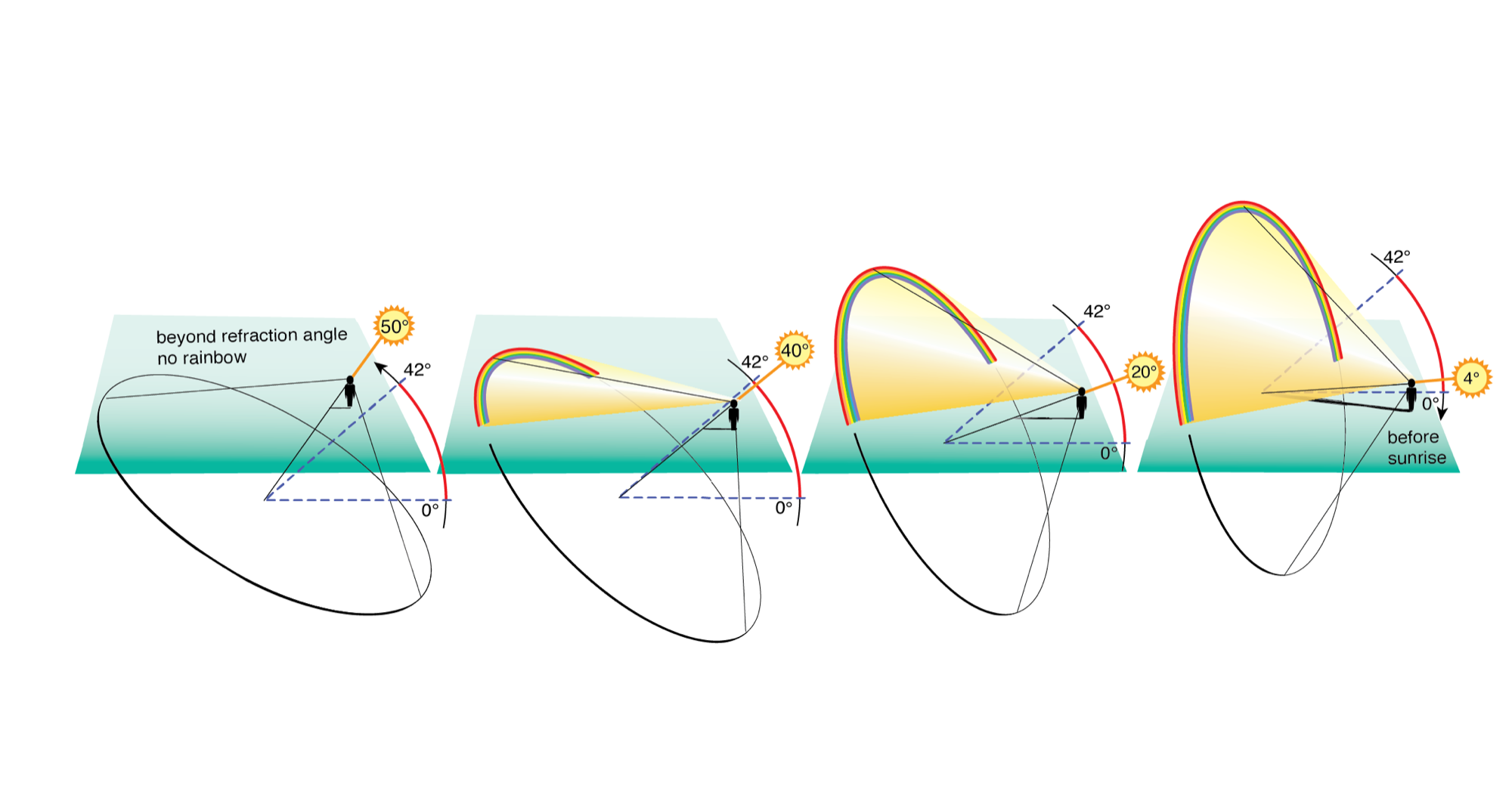

Each drop in a rain shower acts as a mini prism. The droplet bends (refracts) and bounces (reflects) light. The light waves refract as it enters the drop, reflect off the back of the drop, and then refract once more as it leaves the droplet. Since each color wavelength has different energies, they refract at slightly different angles, allowing the colors to separate out into the spectrum we see in a rainbow. The more uniform the raindrops are in size, the more brilliant the rainbow, “where the colors are more distinct,” explains Businger. The refraction and reflection of light results in a 42-degree angle. “If the sun is at your back, and you look at the shadow of your head, the rainbow is 42 degrees above that point,” he explains.

Hawaii also has a special lock on rainbow phenomena, Businger argues in his paper. “I moved to Hawaii in 1993 and I was stunned by how many rainbows there were.”

The combination of trade winds, cumulus cloud coverage, mountainous terrain, and clean air all contribute to rainbow sightings on the Hawaiian Islands. The mountain peaks force the trade winds from the ocean to rise and cool, creating “an open pattern with rain showers and holes in the clouds for the sun to enter,” explains Businger. This is unlike places in the Pacific Northwest, for instance, where there is a lot of rain but stratiform clouds block out the sun. Additionally, Hawaii is known for its clean marine air. “With the exception of some volcanic haze, we have a very clean atmosphere here because we’re so far away from pollution sources,” says Businger. “And that results in very strong sunshine that produces a brilliant rainbow.”

Hawaii's mountains are one factor that helps create frequent, bright rainbows. Credit: Steven Businger

These multicolored majesties hold a significant relevance in Hawaiian culture. They adorn license plates and play the role of University of Hawaii’s mascot, the Rainbow Warriors. But their symbolism stretches back further into Hawaiian folklore and language, says M. Puakea Nogelmeier, professor emeritus of Hawaiian language at the University of Hawaii, who advises and collaborates with Businger.

Rainbows often symbolize a boundary, he says, “the veil between the realms of the gods and the realms of the humans.”

The gods dwell in the forested regions

Blocked from view by the thrusting mists and the bright, low-lying rainbow (uakoko-blood rain)

In Hawaiian culture, they’ve signified the presence of the supernatural, royalty, sacred entities, and are referenced in a variety of ways in poetry. These observations date back centuries, falling under “part of the priestly sciences,” Nogelmeier says. “They had to be able to observe and identify and interpret physical phenomena that were considered significant.”

Double rainbow in Kaiwi. Credit: Steven Businger

The iridescent bands of a rainbow—in any shape or form—are a sight to behold: a small streak of color shimmering in the clouds, a bright pillar bleeding into the vista, a radiant bridge arching across the sky. In the Hawaiian language, there are specific terms for these diverse shapes, explains Nogelmeier.

“In English, I think we use ‘rainbow’ a great deal: a rainbow in the clouds, a rainbow over the ocean. Where Hawaiian would distinguish that more and say, ‘no, it’s a pillar of color. It’s a band.’ It’s a different kind of specificity.” For instance, low, Earth-clinging rainbows are ‘uakoko,’ standing rainbow shafts are called ‘kāhili,’ faintly visible rainbows are ‘punakea,’ and moonbows, which are visible by the light of the moon, are ‘ānuenue kau pō.’

“One of the valleys here has a rainbow most all day long. It’s simply a matter if there’s a standing mist and wherever the sun is, watch the other side for the rainbow,” says Nogelmeier. “It’s actually supposed to be the physical embodiment of the end of a legend. That is the person who was then defied and became sort of a supernatural, continuing to appear and watch over the people. Tuahine, the sister rain, always carries a rainbow with it.”

The beauty of rainbows resonates with many people. Businger says that rainbows can be a way to connect with nature.

“It causes us to stand still and to really look at what’s happening,” he says. To help make rainbow chasing more accessible, Businger, Paul Cynn, and his colleagues have developed the RainbowChase app, which utilizes radar weather information that helps users in Hawaii determine if they can see a rainbow nearby. The team is planning on expanding the app’s coverage across the U.S. and to more countries.

However, Businger says that where we commonly see rainbows might change due to climate change. For a future study, Businger and a colleague are using climate models to understand change in the distribution of rainfall. “It’s getting drier some places and wetter other places. In addition, the clouds are becoming … less stratiform and more cumulus in some places,” he says. The results have yet to be published, but Businger says, “it’s that change in the nature of the clouds and it’s a change in how much rain you have that will change the distribution of rainbows.”

Can’t get enough of these vibrant spectacles? Take a look at the diversity of rainbow phenomena and Businger’s explanation of the science behind them in the gallery below!

Rainbows aren’t only seen during the day. You can see “moonbows” at night. “When you see the moon, you’re generally looking at the reflected light from the sun,” Businger says, but adds that you need a lot of light from a full or nearly full moon to see a moonbow. Since the light is dimmer, a moonbow has less distinct colors than a rainbow, but “in Hawaii, because we have such clean air, the moonbows are brighter and can be photographed.”

Perhaps most famously captured in this video, the double rainbow is a result of two reflections inside droplets—instead of just one. The primary, more distinct rainbow is created with the typical refraction and reflection seen in single rainbows. But, for the second bow, the light “is hitting the drop in such a way that it’s actually going into the bottom of the drop,” explains Businger. The light refracts as it enters, reflects twice internally, and refracts once more before leaving the droplet, he says. “The angle it leaves is 51 degrees. And that 51-degree angle puts it nine degrees higher than the 42 degrees of the primary bow. So it’s nine degrees higher in the sky,” he says. “And because there’s an extra reflection, the colors are reversed, with red on the bottom and indigo on top.”

It’s even possible for more than two reflections inside the droplets—so you could, in theory, get a triple, quadruple, and quintuple rainbow, says Businger. But unfortunately, these are hard to come by. “With each reflection, you’re losing a bit of light out the back of the drop. And so it’s very rare to be able to see these other rainbows.”

If you’re flying through a cloud in an airplane or helicopter, you might spot a glowing ring around the shadow of your craft. “It’s kind of like looking at the rainbow pattern on a CD,” says Businger. These halos, known as “glories” or “solar glories,” are caused by the scattering of sunlight by uniform cloud droplets, explains Businger. A similar phenomenon can be seen around the sun or moon, but you have to be careful not to blind yourself if you try to view it, he says. “If you have a high cloud that is thin and is made of uniform cloud droplets, it’ll form something called a ‘corona,’ which is a rainbow color around and close to the sun or the moon.”

Not all rainbows fan out the full spectrum of color. There are two types of rainbows that display a single color. Red rainbows can occur when the sun hangs at a low angle. If there’s a little bit of pollution in the air, the particulates cause the blue and green light to scatter away, he explains. “Something like a little smoke or smog from the Kilauea volcano can create a situation where most of the green and blue light are scattered out. What’s left behind is a streak of reddish-orange light.”

The second type is the white rainbow, also known as the “cloudbow” or “fog bow.” You might catch a glimpse of these faint, glowing arches in wisps of clouds, mist, or fog, where the drops are so small, that they scatter the light and blur out the colors. “Since they all kind of blur together, they become white light again and that gives you a white rainbow,” he says. “The place where I’ve seen the most white rainbows is at the top of Mauna Kea. You’re standing at the top looking down on the cloud deck, which is really close to you in the afternoon, and the sunshine is pouring down and you see this white bow.”

If you stood next to your friend to watch a rainbow, you both would be viewing colors from two different sets of droplets in the rain shower. That means you’re technically viewing two different rainbows. “Each rainbow comes out from the shadow of [each viewer’s] head at 42 degrees,” says Businger. “That’s why no two people see exactly the same rainbow.”

So, the next time you spot a rainbow, what you see is your unique colorful beam of light—a rainbow of your own.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.