‘Gladiator II’ And The Evidence For Colosseum Naval Battles

Lots of moments from “Gladiator II” are fiction. But some scientists think mock naval battles in the Colosseum totally happened.

This is an article from our newsletter “Science Goes To The Movies.” To get a story about the science of popular movies and TV in your inbox every month, subscribe here.

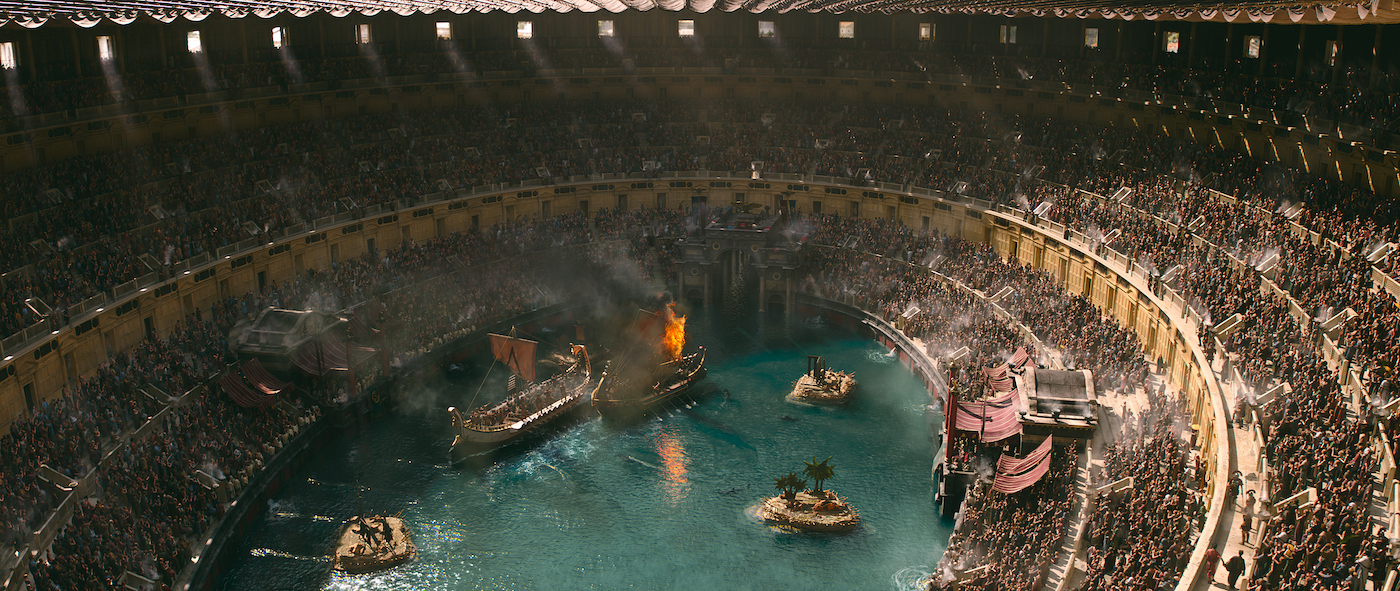

Welcome back to the “Gladiator” universe! This movie has everything—decapitations, a monkey senator, an inexplicable newspaper, and an epic naval battle performed inside the walls of the Colosseum.

When I saw the Colosseum in “Gladiator II” filled with water like a bathtub, I thought it was an artistic liberty. But according to some Roman historians, mock naval battles, known as naumachiae, happened at least once in the Colosseum, likely around the time of its opening in 80 CE.

Scientists and archaeologists have learned a lot from analyzing the Colosseum’s sewers, like what animals died there and even what snacks guests ate, but there’s an ongoing debate among archaeologists as to whether the Colosseum was actually flooded for naumachiae.

Let’s look at the evidence.

In the early aughts, Dr. Martin Crapper, a civil engineer now at Northumbria University, visited the Colosseum to learn if flooding its interior was possible or practical. The resulting paper, published in Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 2007, uses archaeological evidence combined with modern hydraulic engineering to determine how quickly the Romans could have flooded the Colosseum and where they may have gotten the water from.

Crapper found that the underground chamber at the base of the Colosseum, known as the hypogeum, was partially lined with mortar—a clear sign of early waterproofing. As for the water’s origins, Crapper noted that one branch of the Aqua Claudia aqueduct—an addition built by Emperor Nero (37-68 CE)—that was located atop a nearby hill could potentially have brought water from what is now called the Aniene River into a network of pipes inside the Colosseum. Using the Romans’ meticulous records of the size of the aqueduct channel (4.8 feet high by 2.8 feet wide) and rate of waterflow (about 75.2 cubic feet per second), Crapper estimated that the Colosseum could have been filled in about 2 hours and 15 minutes. Seventeen years after the paper was published, he thinks it could have happened even quicker.

“My more recent musings are that they would have constructed a temporary kind of wooden aqueduct from Nero’s branch of the Aqua Claudia … essentially down the middle of the road” by the amphitheater itself, rather than all the way up the hill, he says. With large water containers close to the Colosseum, it could have taken as little as 40 minutes to fill the hypogeum to a depth of one and a half meters.

However, this is all speculation. No actual water pipes have been found inside the Colosseum—just stone inlets where they may have gone, and the fountains that would have used them.

Dr. Heinz-Jürgen Beste, an archaeologist at the German Institute of Archaeology in Rome who has studied the amphitheater, says that this lack of evidence, and the relatively small size of the Colosseum, have led some archaeologists to believe that naumachiae weren’t possible. But he believes the Romans might have used smaller ships made specially for the event. He adds that there would have been an incentive to hold such mock battles.

“It was politically important for Emperor Titus to show what was possible in this new amphitheater, surpassing all his predecessors, with a naval battle and gladiatorial combat,” Beste said in an email.

By analyzing the Colosseum’s groundwater sources, geologists have also found evidence that naumachiae may have been possible. In 2020, Dr. Cristina Di Salvo, a geologist at the National Research Council of Italy, published a geological model of the Colosseum and its surrounding areas. It showed that the amphitheater was built on fluvial soil, meaning that flowing water existed below it.

The model shows how water easily flowed through the Colosseum and away from it, almost like that was an intentional function of its structure, Di Salvo hypothesizes. It was also built in a valley, where water could flow downward toward it then drain out through sewers, aided by porous sedimentary deposits, into the nearby Tiber River, she says.

Di Salvo isn’t an archaeologist and can’t definitively say that the Romans flooded the Colosseum, but “the evidence is clear,” she says, that waterflow was a major consideration in the Colosseum’s construction, whether for naumachiae, fountains, or simply cleanup: “Water was a fundamental thing here.”

Much like “Gladiator,” “Gladiator II” is full of spectacle and standout performances. Russell Crowe would be happy—I was entertained. But because of its predictability and occasional lack of passion, I still give it a thumbs down.

“Gladiator II” is in theaters now.

Emma Lee Gometz is Science Friday’s Digital Producer of Engagement. She’s a writer and illustrator who loves drawing primates and tending to her coping mechanisms like G-d to the garden of Eden.