Five Back-To-School Books For Science-Loving Kids

A handful of good reads for the shark fans, budding architects, and other curious kids in your life.

School days are here again, so stuff your kid’s backpack with some worthy reading material. Here’s a short list of science-themed books for kids that we adults thought were pretty cool, too.

Smart About Sharks

By Owen Davey

Flying Eye Books (August 2016), ages 8 & up, $19.95

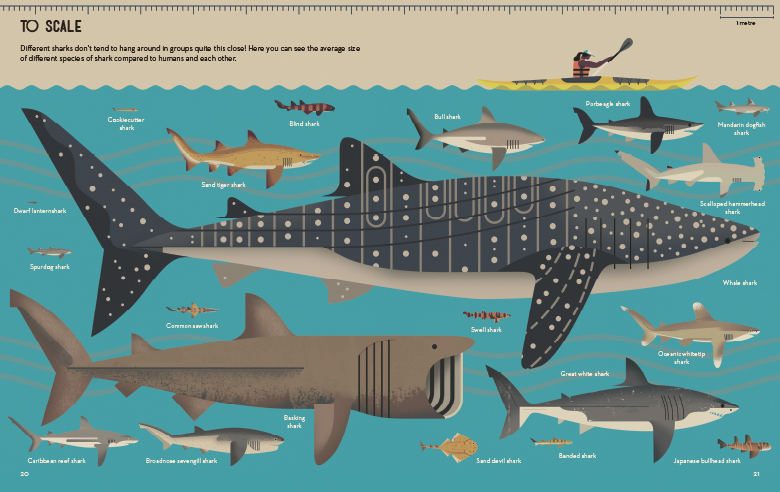

Sharks have been around for millions of years, yet they never get old. British author/illustrator Owen Davey’s Smart About Sharks is a pictorial sampling of the biology and behavior of the more than 500 shark species that swim our seas. Ever heard of a cookiecutter shark? This species suctions onto victims with its mouth, then “twists its body around and cuts a circular chunk of flesh from the creature.” Meanwhile, blacktip sharks have been observed herding fish into “bait balls,” which they attack “until nothing but a shower of fish scales is left.” Kids might particularly enjoy a section reserved for superlative sharks, which “awards” certain species for singular traits. Take nurse sharks, which lie next to each other along the seafloor and “probably deserve the title of laziest shark.” Davey’s stylized illustrations are also appealing: The skillful assembly of geometric shapes and patterns captures the essence of his carnivorous, cartilaginous subjects. (Readers keen on Davey’s aesthetic might also check out Mad About Monkeys.)

Ada Twist, Scientist

By Andrea Beaty/Illustrated by David Roberts

ABRAMS (September 2016), ages 5–7, $17.95

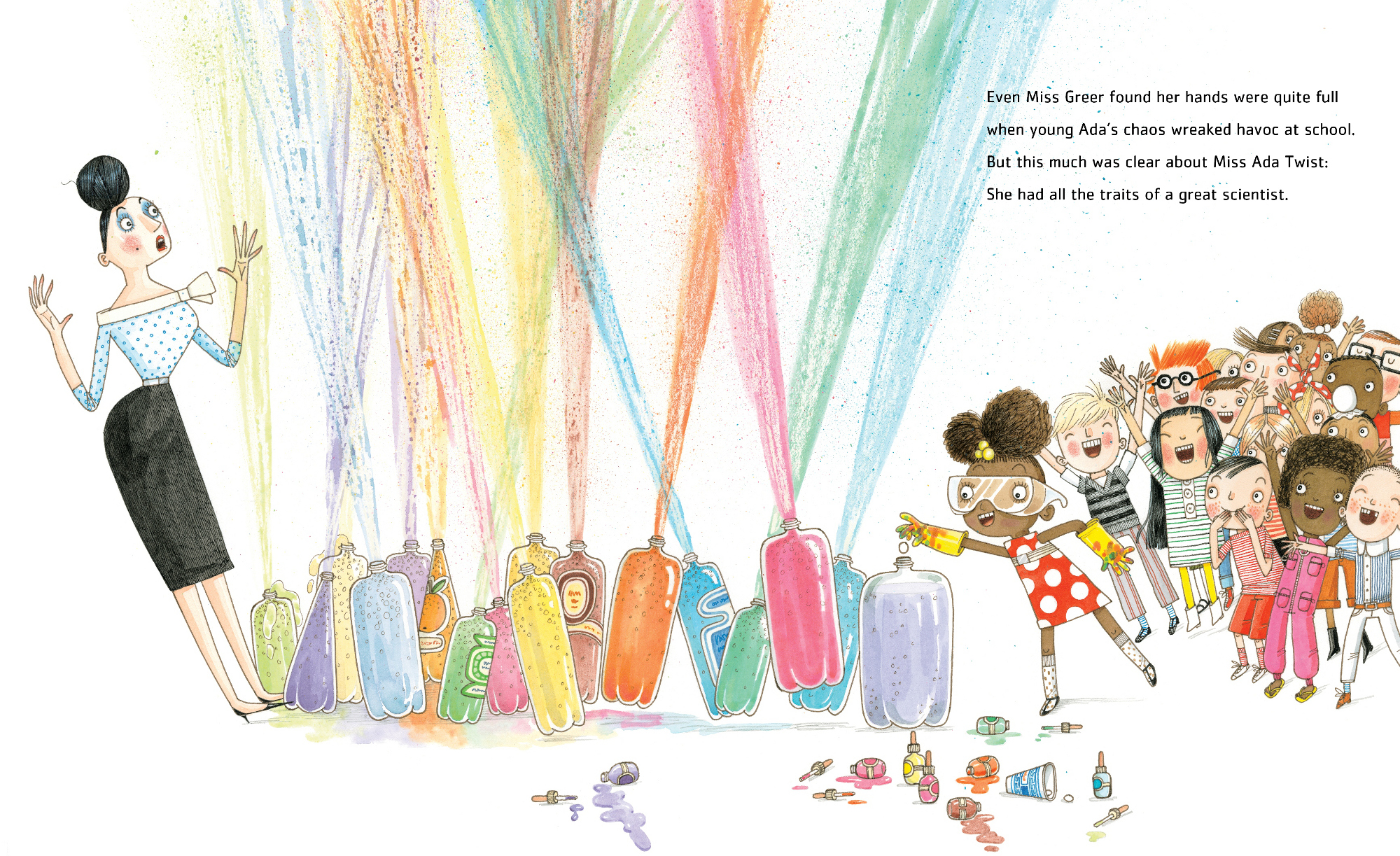

If your child’s favorite word, is “why,” she’ll find a kindred spirit in Ada Marie Twist. After quietly observing the world around her for the first three years of her life, little Ada Marie (her names are derived, respectively, from Ada Lovelace, widely considered to be the first computer programmer—see review below!—and Marie Curie, who discovered radium) stuns her family with an onslaught of questions about how the world works. And she never stops asking. Impressed by the giant clock in their house, for instance, she inquires, “Why does it tick and why does it tock? Why don’t we call it a granddaughter clock?” In seeking answers, Ada sets up experiments, leaving cluttered messes and general chaos, in her wake. It takes a particularly vexing mystery—the source of a strange smell—for Ada’s family to make peace with her scientific pursuits (spoiler alert: They join her investigation). Andrea Beaty’s clever rhyming is accentuated by David Roberts’s adorable illustrations, which brim with creative details that will stoke any young readers’ curiosity. (If you like Ada Twist, Scientist, there’re two other books—one about an architect and one about an engineer—in the series.)

From Ada Twist, Scientist, by Andrea Beaty and illustrated by David Roberts (ABRAMS, 2016)

Who Built That? Bridges

An Introduction to Ten Great Bridges and Their Designers

By Didier Cornille

Princeton Architectural Press (October 2016), ages 8–12, $17.95

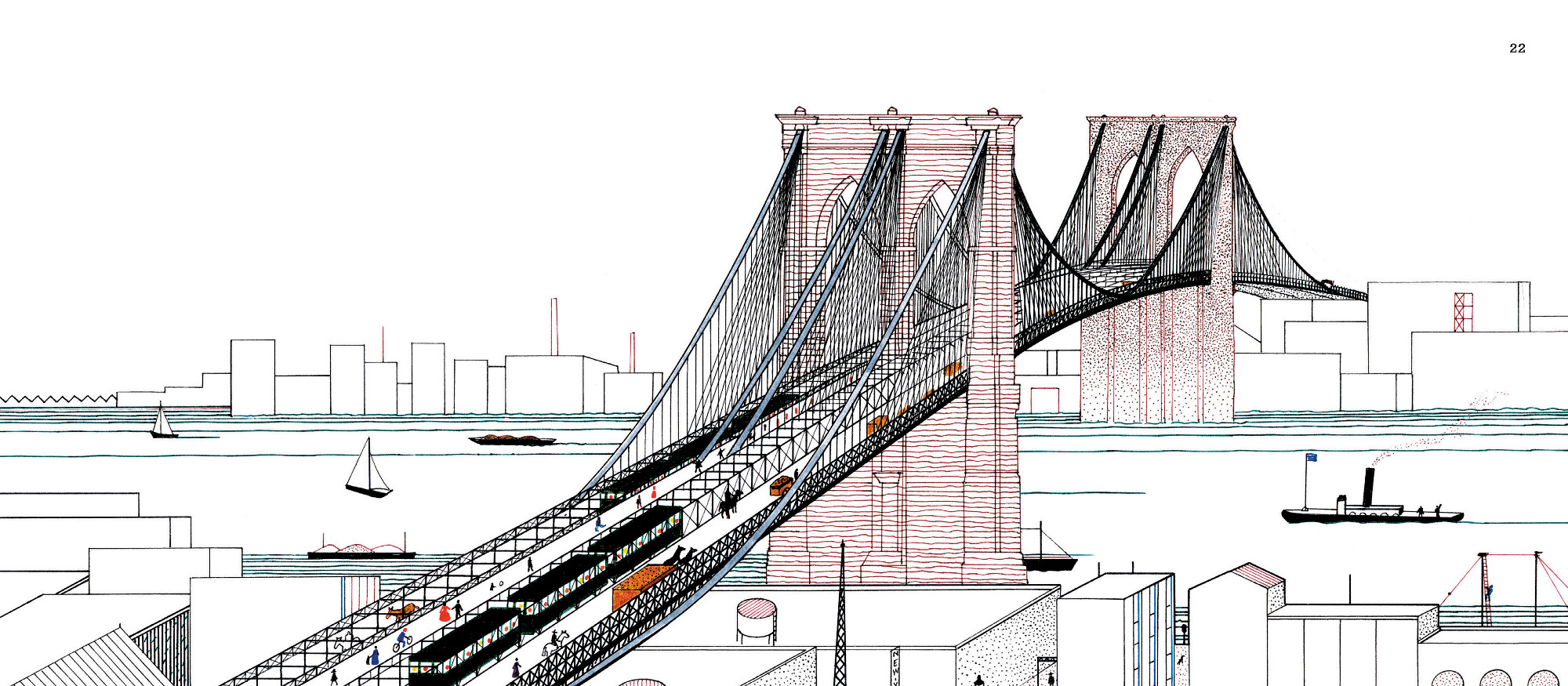

In 1883, a parade of circus animals, including 21 elephants, marched across the Brooklyn Bridge in a public demonstration of its sturdiness. Indeed, at the time of its inauguration, it was the biggest bridge ever built. This iconic feat of engineering is one of multiple innovative bridges that Didier Cornille’s tours in his book, the latest installment of the Who Built That? series (which has also covered skyscrapers and modern houses). Cornille’s clean, sparingly colored line drawings—which span long, rectangular pages befitting their subject matter—focus on important architectural and engineering elements, such as trestles and girders, while also drawing attention to scale. For instance, one picture depicts a side-by-side lineup of cars, trolleys, and pedestrians on Australia’s Sydney Harbour Bridge, emphasizing its status as the longest wide-span bridge in the world. Kids will also meet the brains behind the bridges, such as architect Norman Foster and designer Michel Virlogeux, who together conceived of the Millau Viaduct, a structure supported by cables attached to masts that traverses Europe’s Tarn Valley. Soaring 1,125 feet at its peak, it’s the tallest cable-stayed viaduct in the world. Now that’s an example of higher-level thinking.

From "Who Built That? Bridges: An Introduction to Ten Great Bridges and Their Designers," by Didier Cornille (Princeton Architectural Press, 2016)

The Darkest Dark

By Chris Hadfield/Illustrated by The Fan Brothers

Little, Brown and Company (September 2016), ages 4–8, $17.99

Chris is a space-obsessed kid. He flies a (cardboard) spaceship and takes trips to Mars (in the tub). He’s also scared of something that freaks out plenty of other children: the dark. In one scene, a wide-eyed Chris lies in bed with the covers pulled up past his nose, surrounded by the glowing orbs of aliens conjured by his active imagination. But on the evening of July 20, 1969, Chris encounters a darkness he never fathomed when he and his family gather round a neighbor’s TV to watch history unfold: Neil Armstrong taking his first step on the moon. “The darkness of the universe was so much bigger and deeper than the darkness in his room,” writes author and Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who based the protagonist of The Darkest Dark on his younger self. “For the first time, Chris could see the power and mystery and velvety black beauty of the dark.” Hadfield grew up to explore that darkness. Maybe some day your kids will, too.

From "The Darkest Dark," by Chris Hadfield and illustrated by The Fan Brothers (Little, Brown and Company 2016)

Ada’s Ideas

The Story of Ada Lovelace, the World’s First Computer Programmer

By Fiona Robinson

ABRAMS (August 2016), ages 6–9, $17.95

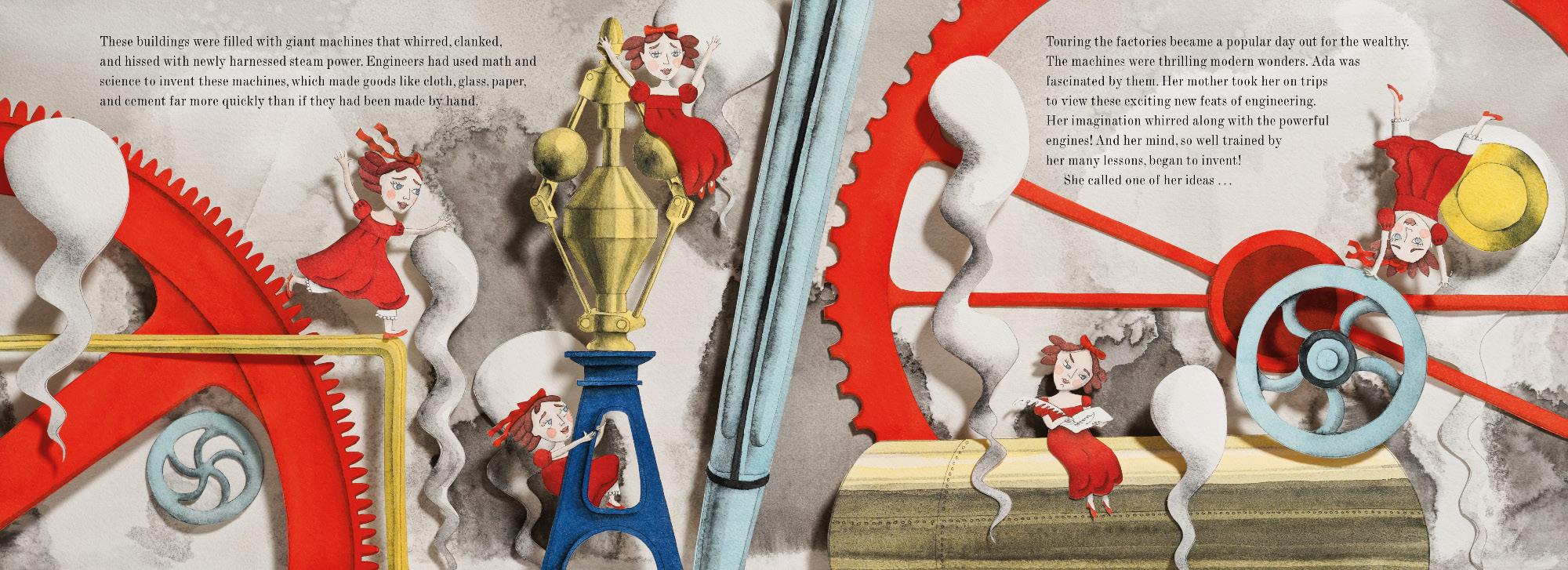

Ada’s Ideas, an illustrated biography by Fiona Robinson, opens with a whimsical portrait of a young woman with a bow in her hair, riding a dappled steed through the sky. The woman is Ada Lovelace, who once “dreamed of making a steam-powered flying horse,” and who is now widely considered the world’s first computer programmer. Through delightful cut-paper illustrations, Robinson touches on formative moments in Lovelace’s brief life (she died at 36). For example, while growing up during the Industrial Revolution, Ada joined her mathematician mother on factory tours. A two-page spread of a young Lovelace climbing and cartwheeling over gears amid puffs of steam illustrates how her “imagination whirred along with the powerful engines!” But Lovelace was a dreamer and a doer. At 17, she met the polymath Charles Babbage. When he designed his “Analytical Engine”—a progenitor to the computer, in theory—Lovelace offered to write the program. Her inventive mind even went one step farther than her counterpart’s: While Babbage thought a machine like the one he designed would only crank out calculations, Lovelace “believed it could be programmed to create pictures, music, and words.” Talk about prescient. (For more on Lovelace and Babbage, check out this SciFri segment.)

From "Ada’s Ideas The Story of Ada Lovelace, the World’s First Computer Programmer," by Fiona Robinson (ABRAMS, 2016)

Julie Leibach is a freelance science journalist and the former managing editor of online content for Science Friday.