Why Fermentation Is So Important To One Of The World’s Best Restaurants

Two chefs at the world-famous restaurant Noma explain why the microbes at work in fermentation are key to unlocking flavors in their food.

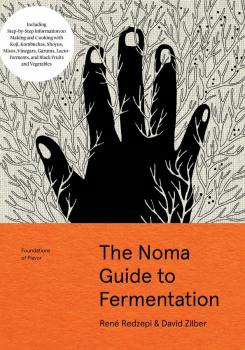

The following is an excerpt of The Noma Guide to Fermentation by René Redzepi and David Zilber.

The Noma Guide to Fermentation

People have always associated our restaurant closely with wild food and foraging, but the truth is that the defining pillar of Noma is fermentation. That’s not to say that our food is especially funky or salty or sour or any of the other tastes that people associate with fermentation. It’s not like that. Try to picture French cooking without wine, or Japanese cuisine without shoyu and miso. It’s the same for us when we think about our own food. My hope is that even if you’ve never eaten at Noma, by the time you’ve finished reading our book and made a few of the recipes, you’ll know what I mean. Fermentation isn’t responsible for one specific taste at Noma—it’s responsible for improving everything.

I believe in fermentation wholeheartedly, not only as a way to unlock flavors, but also as a way of making food that feels good to eat. People argue over the correlation between fermented foods and an active gut health. But there’s no denying that I personally feel better eating a diet full of fermented products. When I was growing up, eating at the best restaurants meant feeling sick and full for days, because supposedly everything tasty had to be fatty, salty, and sugary. I dream about the restaurants of the future, where you go not just for an injection of new flavors and experiences, but for something that’s really positive for your mind and body.

Studying the science and history of fermentation, learning to do it ourselves, adapting it to local ingredients, and cooking with the results changed everything at Noma. Once you’ve done the same and have these incredible products at your disposal—whether it’s lacto-fermented fruit, barley miso, koji, or a roasted chicken wing garum—cooking gets easier while your food becomes more complex, nuanced, and delicious.

I believe in fermentation wholeheartedly, not only as a way to unlock flavors, but also as a way of making food that feels good to eat.

There are thousands of products of fermentation, from beer and wine to cheese to kimchi to soy sauce. They’re all dramatically different creations, of course, but they’re unified by the same basic process. Microbes—bacteria, molds, yeasts, or a combination thereof—break down or convert the molecules in food, producing new flavors as a result. Take lacto-fermented pickles, for instance, where bacteria consume sugar and generate lactic acid, souring the vegetables and the brine in which they sit, simultaneously preserving them and rendering them more delicious. Cascades of secondary reactions contribute layers of flavors and aromas that didn’t exist in the original, unfermented product. The best ferments still retain much of their original character, whether that’s a touch of residual sweetness in a carrot vinegar or the floral perfume of wild roses in a rose kombucha, while simultaneously being transformed into something entirely new.

The Noma Guide to Fermentation is a comprehensive tour of the ferments we employ at Noma, but it is by no means an encyclopedic guide to all the various directions you can take fermentation. It is limited to seven types of fermentation that have become indispensable to our kitchen: lactic acid fermentation, kombucha, vinegar, koji, miso, shoyu, and garum. It also covers “black” fruits and vegetables, which aren’t technically products of fermentation but share a lot in common as far as how they’re made and used in our kitchen.

Notably absent from this book are investigations of alcoholic fermentation and charcuterie, dairy, and bread. (Bread could take up—and deserves—its own separate discussion.) While we dabble with the fermentation of sugar into alcohol, it is almost always en route to something else, like vinegar. We’ve always worked closely with incredible winemakers and brewers and cannot pretend to be masters of their domain. Charcuterie is something that has not yet played a large role in our menus, though over the coming years we intend to dive deeper into fermenting meats as we celebrate the game season each fall. While we do make cheese at the restaurant, it’s often served fresh and unfermented (though we’re no strangers to yogurt and crème fraîche). Whenever we have cooked with artisanal aged cheeses, we’ve left their production in the hands of Scandinavia’s amazing dairy farmers.

Each chapter tackles one ferment, providing some historical context and an exploration of the scientific mechanisms at work. Many of the ideas and microbial players behind different ferments are interconnected, so you’ll see some concepts revisited and developed over the course of the book. For example, in order to make shoyu, miso, and garum, you’ll first need to understand how to make koji, a delicious mold grown on cooked grains and harnessed for its powerful enzymes. That being said, you should feel free to dive in wherever your interests lead you. You’ll still get a thorough understanding of each ferment without reading the rest of the book.

Included with each chapter is an in-depth base recipe, where we put ideas to work and walk you through the steps of making a representative example of each style of ferment.

In most cases, there’s no single “right” way, so the recipes are written with multiple methods and possible pitfalls in mind. We go into quite a bit of detail—more than you may need in some instances—but we want you to feel as comfortable making these ferments as one of our own chefs would be if tasked with making one for the first time. Even though it may require a little patience and commitment, you can and absolutely should produce your own shoyus and misos and garums. Once you taste the rewards of your effort, it’s hard to imagine cooking without them. Plus, it all gets easier the second time around.

After you’ve read the in-depth base recipe for a ferment, you may feel ready to apply the same process to other ingredients, but to give you some inspiration, each chapter also contains several variations, which may illuminate other facets of the same technique. In some cases, these variations diverge in method from the base recipe, but rest assured, we’ll detail these changes and explain why we’re making them.

Finally, following each recipe, you’ll see a few practical applications for the ferment in your day-to-day cooking—many of which are inspired by preparations we make at Noma.

This is a book meant to bring some clarity to a hazy realm of cooking, full of confusing and unfamiliar terminology. We’ve spent the past decade investigating and unraveling fermentation for ourselves, and we’ll try to share what we’ve learned with you. But more important, we want you to come away from this book with the same feeling of exhilaration and wonderment that we have whenever we make and use one of the miraculous products of fermentation.

Excerpted from the introduction to The Noma Guide to Fermentation by René Redzepi and David Zilber (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2018.

René Redzepi is the co-author of Foundations of Flavor: The Noma Guide to Fermentation (Artisan Books, 2018). He’s also the co-owner of the restaurant Noma.

David Zilber is the co-author of Foundations of Flavor: The Noma Guide to Fermentation (Artisan Books, 2018). He’s the Director of Fermentation at Noma in Cophenhagen, Denmark.