East Palo Alto Community Rises Up To Face Rising Seas

As the threat of sea level rise looms over the Bay Area, community members in flood-prone East Palo Alto search for solutions.

This article by Kevin Stark and Ezra David Romero originally appeared on KQED Science, where you can listen to an audio version of the story. This KQED series is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

The first time the streets flooded, Appollonia Grey ‘Uhilamoelangi, known as Mama Dee in her East Palo Alto community, got a little nostalgic. The weather, though severely inclement, at least reminded her of home in Samoa.

“That time I was very happy,” ‘Uhilamoelangi said, about her first Bay Area deluge. “I was outside swimming in the rain, playing in the rain. There was water everywhere.”

But East Palo Alto, with a population of 30,000, is prone to flooding, and three times over the next 30 years, torrential rains devastated the city.

“The last two floods over here, the question is, where was God?’ she said. “Don’t get me wrong. I believe in prayers. But I lived through so many disasters.”

Now, the bay waters being pushed higher by the effects of climate change pose an existential threat to this small community of mostly people of color.

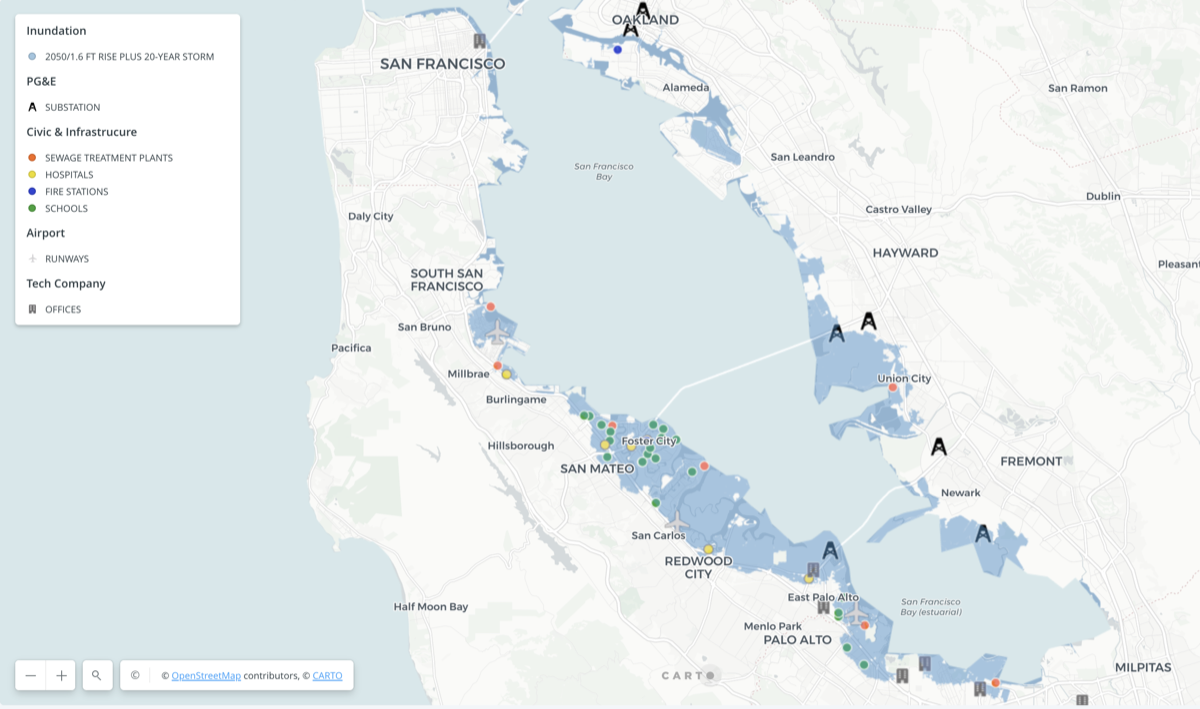

That’s not hyperbole. East Palo Alto is located between San Francisco and San Jose at the western end of the Dumbarton Bridge. Of all Bay Area counties, San Mateo is the most at risk from sea level rise, and of all places in the county, East Palo Alto is one of the most vulnerable to climate-driven inundation.

Roughly 2.5 square miles of ranch-style homes and citrus trees, the city is bound by water on three sides, the San Francisquito Creek, meandering along the southern edge, the bay lying to the north and east.

Already, half of East Palo Alto sits within a federally designated flood zone. According to projections, in 10 years or so up to two-thirds of the land within city limits may regularly experience flooding. By mid-century, those areas could be frequently underwater during high tides.

The effects of climate change are disproportionately impacting communities of color like those in East Palo Alto. Gentrification and an influx of tech behemoths like Facebook, Google and Amazon has changed the makeup of the city, but it’s still largely non-white, with a population of 66% Latino. Many Pacific Islanders like ‘Uhilamoelangi also live here.

Heavy rains regularly swell the creek and flood the city’s eastern sections, and an elevated sea level will severely exacerbate the problem, undermining the viability of East Palo Alto’s working-class community, says Derek Ouyang, a program manager and lecturer at the Stanford Future Bay Initiative who works with community leaders in the city.

“If you were to get to know 100 families in East Palo Alto, maybe 50 out of 100 already are right at that point at which savings are so low that … a flood event … could be that tipping point,” Ouyang said.

Floodwaters swamped more than 1,000 homes here in 1998. In 2012, the creek overtopped its banks, forcing evacuations. The city, working with its neighbors through the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority, reengineered parts of its shoreline to mitigate the risk.

For some in East Palo Alto, flooding and climate change are threatening their homes a second time. Climate refugees here from the Pacific Islands have already fled rising seas, only to face similar threats in a new country thousands of miles away.

Many are collaborating with scientists, the city and the joint powers authority to save homes by restoring and creating a new wetland at the bay’s edge.

While East Palo Alto’s budget, at $41.8 million, is 325 times smaller than San Francisco’s, the city is punching well above its weight in terms of planning for a higher tide.

Yet, it may not be enough. The interconnected nature of both the Bay Area’s ecosystem and infrastructure means that without a regional plan to protect all communities along the bay, East Palo Alto’s best efforts can be undermined, a fact not lost on city leadership and young activists, some of whom are teenagers frustrated they will inherit a city soon to be transformed by the fury of rising oceans and melting ice sheets.

“I just want a plan for the future, because if this happens and there’s going to be flooding everywhere, people should know how to respond,” said Heleine Grewe, a 17-year-old senior at Menlo-Atherton High School.

Grewe’s maternal grandparents emigrated from Tonga, and her dad’s family arrived in a wave of Black Americans who moved to East Palo Alto in the middle of the last century. Many endured blockbusting and other discriminatory housing practices, decades of bad policy rooted in deliberate racial segregation.

Her mom, Leia, is worried the water will come purling through her back door.

“I’m thinking back to the places that weren’t ready,” she said. “Let’s talk about Katrina. That could be us in the next couple of years.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

‘Uhilamoelangi and her husband, Senita, known as Papa Senter, emigrated from Samoa to the United States in the mid-1970s because of the increasing frequency of hurricanes and tsunamis.

“All of us islanders … never have a casual conversation [when we] talk about the rain, the flood,” she said. “Anytime there’s a tsunami at home, on any island, all of us connect and emotions rise.”

But it wasn’t until the mid-2010s that she understood the link between those storms and a warming world.

“I had no clue at all about climate change,” ‘Uhilamoelangi said.

She connected the dots of flooding in East Palo Alto, severe weather in Samoa and rising seas when she met Violet Saena from Climate Resilient Communities, a group dedicated to protecting the Peninsula’s underrepresented residents as the climate crisis grows.

“I can ask questions that sound like stupid questions, but I always have an answer from Violet,” said Mama Dee.

Saena was Samoa’s original climate change officer, creating the country’s first resiliency plan. When she followed her husband to the Bay Area, she saw that the community needed to understand the looming threat. With the help of Stanford students, she went door to door in East Palo Alto, asking people what they knew about the effects of sea level rise.

“It’s easier for me, because I’m a person of color and I do come from the island,” she said. “They see that: ‘Oh, yeah, she’s part of us.’”

Out of those discussions grew community climate groups aimed at educating and involving residents in East Palo Alto’s adaptation plans, as well as helping them with basic needs.

People want to take part in “tangible strategies,” Saena said. “It’s not just the levee. It’s also other things that they can do themselves, like water cisterns or a rain garden system.”

She notes the large number of low-income residents who are going to need help. “(T)hey won’t have the means to be able to buy a car if their car is ruined by flooding. So, what programs can we implement that will help everybody?”

Such a philosophy, if adopted by the entire Bay Area, can lead to a more climate-resilient region, says Elizabeth Allison, who studies the intersection of religion and ecology at the California Institute of Integral Studies.

“I think that we need to adopt a sort of comprehensive ethic of care, actually, when we think about climate change,” she said. This would mean keeping in mind the entire planet, including future generations, “as if they mattered to us as much as our neighbors and friends and families do.”

Care is at the center of the ‘Uhilamoelangis’ organization, Anamantangi Polynesian Voices, which focuses on helping underserved new arrivals. Through person-to-person education, the couple have found a calling.

“We are full-time volunteers for climate change,” Mama Dee said. “To avoid another disaster … where do we run?”

Not to higher ground, she says. The couple want East Palo Alto to remain diverse in the face of both sea level rise and gentrification, so they are sticking it out.

Residents in East Palo Alto will be protected in part by a new, high levee, separating a portion of the city from the San Francisquito Creek, which is connected to the bay.

“This is a 20-year-in-the making project [that] really started in that 1998 flood,” said Mayor Carlos Romero, standing atop the levee overlooking a neighborhood of mostly one-story homes and car-lined streets. “This was inundated. I had friends here who had 4 feet of water in their living room.”

He fears another flooding event would hit East Palo Alto hard, devastating the city much like Hurricane Katrina did to New Orleans.

“If you were to just lie down here and look over the levee, you could see that some of the rooftops are below that levee,” he said. “Basically, it’s another Ninth Ward.”

Where this fancy new levee ends, the deteriorating structure it’s replacing picks up, providing “some protection, but not a lot,” said Tess Byler, senior project manager with the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority, where she oversees a program to help protect the region from sea level rise.

The goal is to have the old levee entirely replaced by 2030. The project has formalized into the Strategy to Advance Flood Protection, Ecosystems and Recreation along San Francisco Bay, less cumbersomely known as SAFER Bay.

Designed to simultaneously withstand a 100-year flood, high tide, and up to a 3.5 feet rise in sea level, this system of earthen and engineered systems, including marshes and levees, will stretch along the shoreline from the Redwood City-Menlo Park border in the north to the Palo Alto-Mountain View line in the south. Altogether, the system will have to contain a projected additional 10 feet to the current mean high-water mark.

The project is split into nine portions, with phase one encompassing East Palo Alto and Menlo Park. Completion of the initial section, scheduled for 2024, will defend nearly 1,600 properties, mostly East Palo Alto homes, along marshes managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. In Menlo Park, the plan calls for restoring more than 550 acres of former salt ponds to marsh.

To enclose the circle of protection around this chunk of the bay will demand cooperation and dollars from private and government landowners as diverse as Caltrans, Facebook, and various utilities and municipalities, says Byler. Special-status wildlife must also be considered.

“It’s just these invisible threads that we have to account for—things that we don’t see—the sanitary sewer alignment—and the electrical towers, which we can,” she said. “And then making sure that we’re being protective of the current high value marsh that is home to many wonderful species of birds and animals.”

Much has yet to be decided, Byler says, including figuring out who is going to build the levees and how to clean up arsenic contamination left in the soil from an old hazardous waste plant.

Still, she has confidence in the project, not only due to widespread community buy-in, but because the various entities appear to be working together, albeit not at the same pace. She says matching state money may add to the financing, which is almost complete.

“We have the funding for East Palo Alto, so that will be our initial focus,” she said.

The levee system is just one bite-size solution, though. Protecting critical infrastructure like Highway 101 will take a regional approach that includes every county in the Bay Area, says Len Materman, CEO of the San Mateo County Flood and Sea Level Rise Resiliency District.

“We’re not there yet, by all nine counties,” he said. “The sooner that everybody’s on board, the better.”

One reason local stakeholders tend to expand the conversation to the entire Bay Area when they talk about solutions is that what happens in East Palo Alto doesn’t stay in East Alto, at least when it comes to the effects of climate change. A catastrophe here will ripple through the region to affect millions of inhabitants in dozens of cities bordering those on the shoreline most at risk.

The Grewes’ at-risk rent home, for instance, is roughly the same distance above sea level as the off-ramps to and from the Dumbarton Bridge. A deluged bridge could mean shutting down one of the major arteries connecting the East and South Bay, throwing the region’s already overburdened transportation system into disarray.

The same type of snowballing effects holds true for water and fuel distribution, communications systems and electricity, said Mark Stacey, an environmental engineer at UC Berkeley. The Bay Area is one interconnected ecosystem, he says, and every seawall, every dredge, every change to the bay’s edge has an impact.

In East Palo Alto, flooding could trigger cascading crises across the region.

“As we transform our shorelines or as our shorelines are transformed for us by sea level rise, the tidal dynamics in the bay are themselves altered,” Stacey said. “Local changes in the shoreline can have regional effects on high water levels.”

As tides constantly pulse into San Francisco Bay, the largest estuary along the West Coast, they sometimes dissipate gently across wetlands, and at other times raise the water level when pushing off seawalls along the shore, Stacey says.

As different communities harden their shorelines against the water’s rise, future tides will slam against these seawalls, amplifying their power elsewhere along the bay and creating a feedback loop that will force the water several inches higher. This will impact millions of Bay Area residents. The southern part of the bay where East Palo Alto is located is most vulnerable to this amplification effect.

Jessica Fain, planning director for the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, says East Palo Alto is a “sweet spot” where the Bay Area has the opportunity to address in one place many of the overlapping challenges related to sea level rise.

“All lines point to here,” she said.

The premise of the regional strategy that Fain is helping to design, called Bay Adapt, is that rising sea levels will affect all aspects of life. The agency, with no original mandate to take on sea level rise, has had to build a new kind of collaboration between cities, counties, businesses and people. It can use the carrot of grants that include guidance to conform to regional goals. Or it could try to gain a broader mandate to encourage good projects and reject unhelpful ones.

“But we’re not quite there yet,” Fain said.

Absent a directive to force cities and counties to coordinate their levees and other solutions, BCDC is working with community groups around the bay to encourage buy-in.

At the group Nuestra Casa in East Palo Alto, program director Julio Garcia runs classes, workshops and focus groups to help give people a seat at the table in the creation of BCDC’s plan.

“If we didn’t have COVID-19, [climate change] is the number one crisis that we are facing,” Garcia said. “As a community of color, people who are workers, it is really important. Because if houses start flooding, where are we going to be moving to?”

The Grewes are both members of the group, where Heleine teaches an environmental justice class.

“I would really love it if more surrounding cities would come together and kind of protect our little city,” Leia Grewe said, during a recent meeting.

Garcia’s concern, as well as Heleine’s and Leia’s, is that the expanded marshlands that can protect the homes here could also drive up housing prices.

“We’ll get moved out to like Stockton, Sacramento,” Leia said. “And I hate that, because when you think about East Palo Alto … a lot of our family members can’t come back. We can’t afford the property here.”

East Palo Alto’s youngest City Council member, 27-year-old Antonio López, says he understands the Grewes’ concerns about gentrification.

“We here, certainly in the city, are fighting for you to stay here and be able to have a voice at the table,” he said. “The levees are just a symbol of us having that fighting chance of staying here.”

López keeps a photo on his phone of San Francisquito Creek, swollen with rainwater, brown with mud, an inch below spilling over into neighborhood streets.

At the same spot the photo was taken, a green steel levee hugs the gentle turns of the creek—a section completed by the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority in 2019. East Palo Alto, working with the authority, widened the creek channel, rebuilt salt marshes and engineered the levee.

Looking at the photo, “I see the anxiety of flood levels, but I also see opportunity and a reminder of where we need to be,” López said.

Ezra David Romero is a climate reporter for KQED News in San Francisco, California.