Crafting Inclusive Narratives: The Role Of Sensitivity Consultation In Media Design

We share what we learned about how to design accessible media when telling stories about the deaf community.

SciFri Findings is a series that explores how we understand the impact of science journalism, media and programming on our audiences. Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest reports!

Often when we think of language accessibility, we think of non-English speakers. However, language can take many forms, including American Sign Language, and deaf community members can face unique challenges in healthcare settings. Starting in August of 2023, D. Peterschmidt, Science Friday’s radio producer and Diana Plasker, Science Friday’s event manager, wanted to help tell the story of how healthcare inequities affect the deaf community with guest experts Tamiko Rafeek, patient advocate with Deaf Diabetes Can Together in Tucson, Arizona, and Dr. Michelle Litchman, medical director of the intensive diabetes education and support program at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. This Zoom session was then turned into a radio story and aired in October of 2023.

There is still some debate on the capitalization of the word “deaf” well as the use of the terms “deaf people” or “deaf community.” After discussions with a sensitivity consultant, we decided to use uppercase “D” for a self-describing organization (e.g. Deaf Diabetes Can Together), or where our style guide recommends Title Case (like the name of the Zoom event “Designing Better Healthcare With The Deaf Community”). Otherwise we use lower case “d” and “deaf community,” as it is inclusive of those who are deaf, deaf-disabled, hard of hearing, parents of deaf children, and other individuals.

Our goal for this story was to highlight healthcare programs co-designed with deaf patients, to raise awareness of the challenges the deaf community face in healthcare systems, to extend outreach to both hearing people and healthcare providers who might be listening, and to provide both practical and legislative steps that can make the healthcare system more inclusive and accessible to underserved populations beyond the deaf community.

As science journalists and communicators, no matter how much we try to keep up with issues facing different marginalized communities we cannot know the full extent of our knowledge gaps without a little outside help. To achieve our goals, producers for this story agreed a sensitivity professional should be hired to provide consultation. Sensitivity work refers to reviewing content for misrepresentation, lack of understanding, narrative, and offensive content with respect to marginalized communities. We chose to hire a sensitivity professional because it would help increase the inclusivity of the program and reduce potential harm to the deaf community.

As part of other work-related sensitivity professionals Ariel Zych, director of audience, found a sensitivity professional who could provide guidance on the deaf community. This included sensitivity consulting to improve our plan for the program. We had three main objectives for this work. First, we wanted to ensure that the deaf community was represented accurately and fairly. Second, we wanted to understand whether the accessibility measures we had in place—like whether and how to use interpreters and captioning, sourcing experts and interpreters, and presenting our published materials— were adequate. Lastly, we hoped to hear insights on areas where we could grow or improve, specifically looking for suggestions to reduce or prevent further harm to the deaf and deaf adjacent communities. Costs for the sensitivity analysis were allocated from our freelance budget. We asked the consultant to review the program design and logistics, our marketing materials, and our content in their analysis. Science Friday always asks sensitivity professionals if they would like to be credited publicly in our final content. Due to the stigma of marginalized identities, some may prefer anonymity or deniability. For those who want their contributions to the story to be acknowledged, we provided proper crediting for this sensitivity work.

One of our top priorities was to ensure that the Zoom session welcomed the deaf community and took their accessibility needs into account. Science Friday audience and radio teams considered questions like, how do we make sure the Zoom event will allow hearing and deaf participants to fully engage with event panelists? Producers also needed to create marketing materials for the story to let deaf community members know there would be interpretation available. The Shutterstock icon was chosen after conducting a Google search image for ASL interpretation signs. Our events manger prominently added the icon to the promotional graphics and also wrote out “ASL Interpretation Available at Event” for hearing audiences, including parents of deaf children and children of deaf adults.

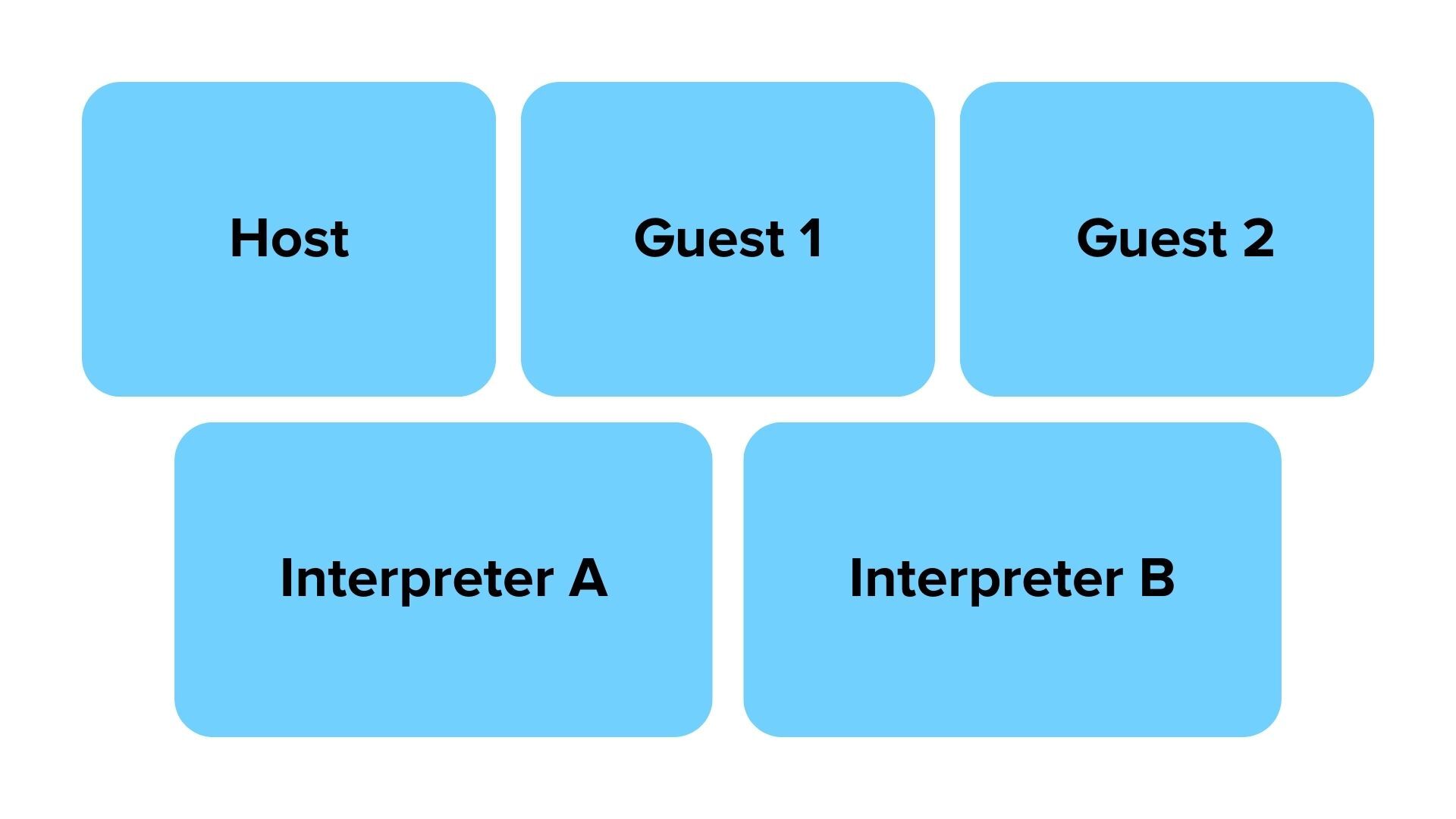

Our show itself incorporated recommendations from the sensitivity professional on how to visually arrange our guests and interpreters for higher impact, helping us address equity and accessibility issues. Positioning confers association, hierarchy, and can increase or decrease the audience’s view of an interpreter. Our sensitivity professional suggested that interpreters should be assigned to specific individuals prior to the event, and positioned accordingly. As part of this segment we had two guests, two interpreters, a host, a radio producer, and an event producer. Our radio producer was behind the scenes and did not require an assigned interpreter for audience translation. Interpreter A was assigned to interpret from English spoken by the host, guest 1, the event producer, and select audience members into ASL. Interpreter B was assigned to interpret from ASL spoken by guest 2 and select audience members into English. We also ensured that computer-generated closed captions were enabled, chat was available, and the Q&A tool was available, facilitating public or anonymous questions.

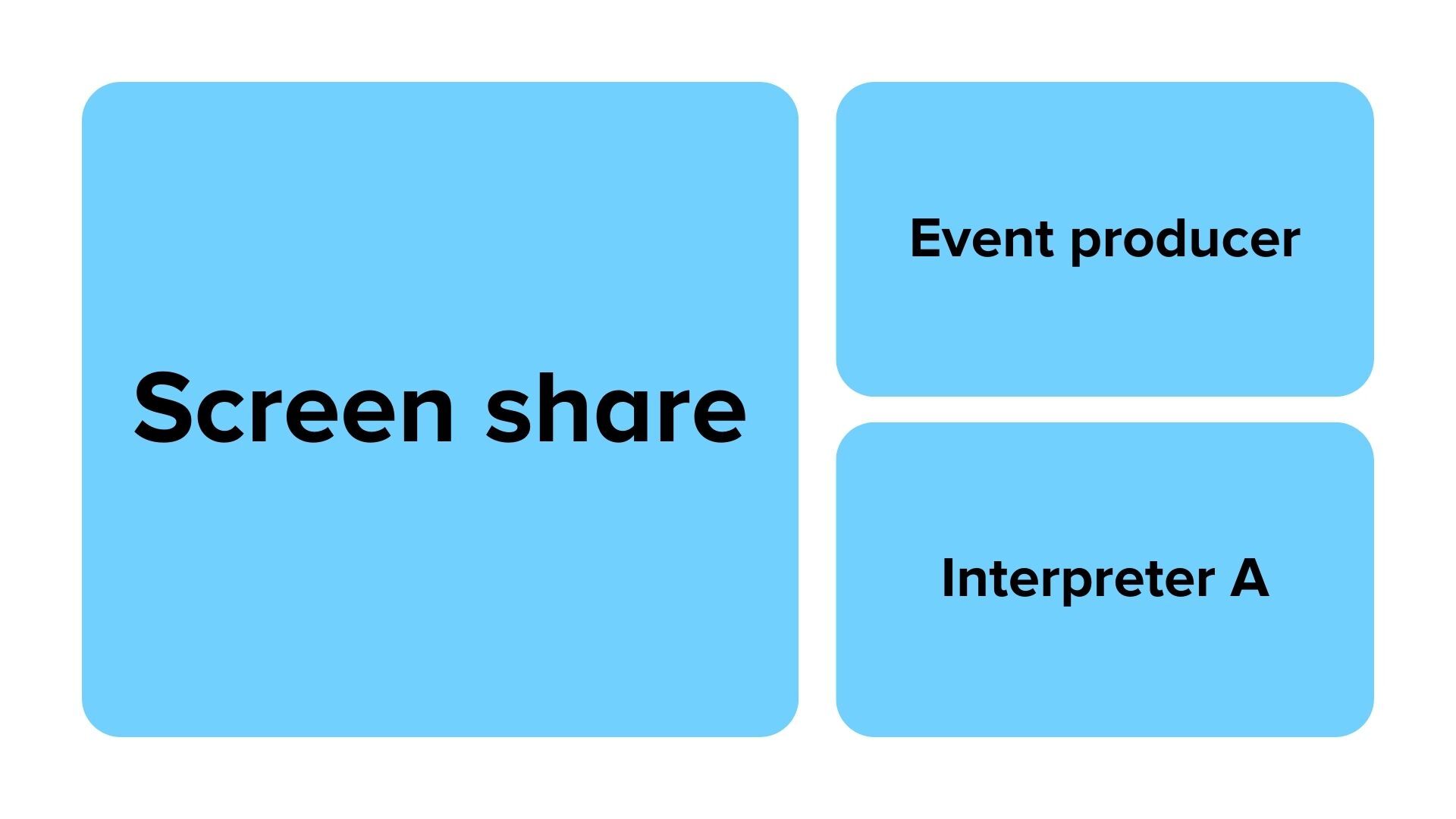

Prior to the entrance of guests, the Zoom windows for the event producer and interpreter A were already stacked side-by-side with the screen share, as seen in Figure 3 above. This allowed audience members to understand the logistics and agenda for the program, including which interpreter is speaking on behalf of each role.

Throughout the interview portion of the session, the gallery view was presented with three windows on top—the host, guest 1, guest 2—and two on the bottom for the interpreters (Figure 4 above). Arranging the presentation in this manner visually aligned each interpreter with their assigned roles.

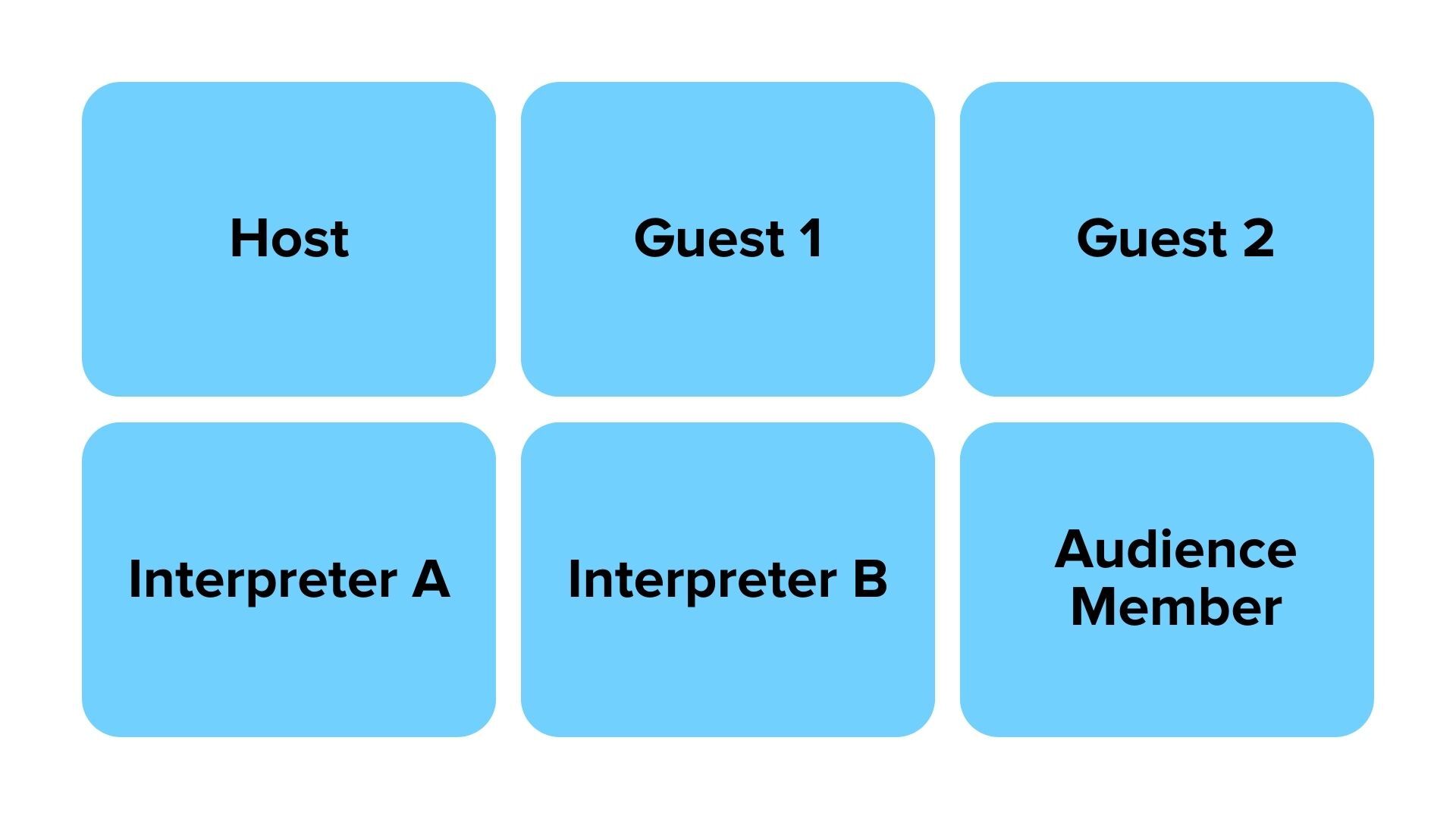

During the audience Q&A portion, the visual arrangement added a third camera on the bottom row (Figure 5 above). Audience members were instructed to type and submit their questions in the Zoom Q&A panel. The event and radio producers chose which questions to elevate based on their relevance to the conversation and the experts’ fields. We requested audience members add a specific word with their questions to clarify how they would like their questions asked. These included: 1. VIDEO, where the camera would be on so they could ask questions via ASL; 2. MICROPHONE, where they would speak into their microphones via voice with no camera; or 3. HOST, where the audience member would not be on camera or microphone, and the host would read their question for them. For example, “What is the best way to implement a new system? VIDEO,” would allow for someone to ask their questions on video with ASL interpretation available.

After the Zoom session, radio staff also needed to translate the information from the online event to a radio story for larger audiences. When switching mediums, our radio producer had to consider how to change this from a visual event to a story that is primarily auditory, while still ensuring that deaf community members can engage with the content. Throughout the session, producers advised the host to welcome the audience member and provide a short descriptor of the question to be asked. For example, “Jane is going to join us to ask a question about equity in healthcare. Jane, you should see a prompt to join us via video. When you’re live, you can go ahead and ask your question!” This allowed both Zoom and radio audiences to understand who was asking a question. Additionally, the transcripts for the radio story and the full video of the Zoom session were produced in advance of its broadcast airing. They were released at the same time as the broadcast so that deaf community members could engage with it immediately.

Working with a sensitivity professional provided so many great insights into how we can create our content. By intentionally dedicating space and time to incorporate feedback from marginalized communities, we were able to find ways to reduce unintentional harm and change the design of our program to be more inclusive. There is still work to do, but here are some of the things we learned to incorporate into your next story with the deaf community:

Editorial note: Regarding capitalization for “Deaf” and “deaf,” we believe this is an unsettled issue. For about 30 years, it was common to use capitalization to denote cultural deafness. In recent years, some national deaf organizations, like the National Deaf Center, have decided to use lowercase in their messaging to be more inclusive. Some individuals however, prefer the capitalized version. We have asked our guests to self-describe and capitalize at their request, and use deaf for describing collective communities.

If you want to learn more about this topic, you can read this paper about the unsettled nature of this debate from the deaf community, via Scientific Research.

Nahima Ahmed was Science Friday’s Manager of Impact Strategy. She is a researcher who loves to cook curry, discuss identity, and helped the team understand how stories can shape audiences’ access to and interest in science.