Your Cervical Mucus Is Beautiful

The protective substance is an important barrier between the body and the environment. Here’s how researchers are using it to understand health.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

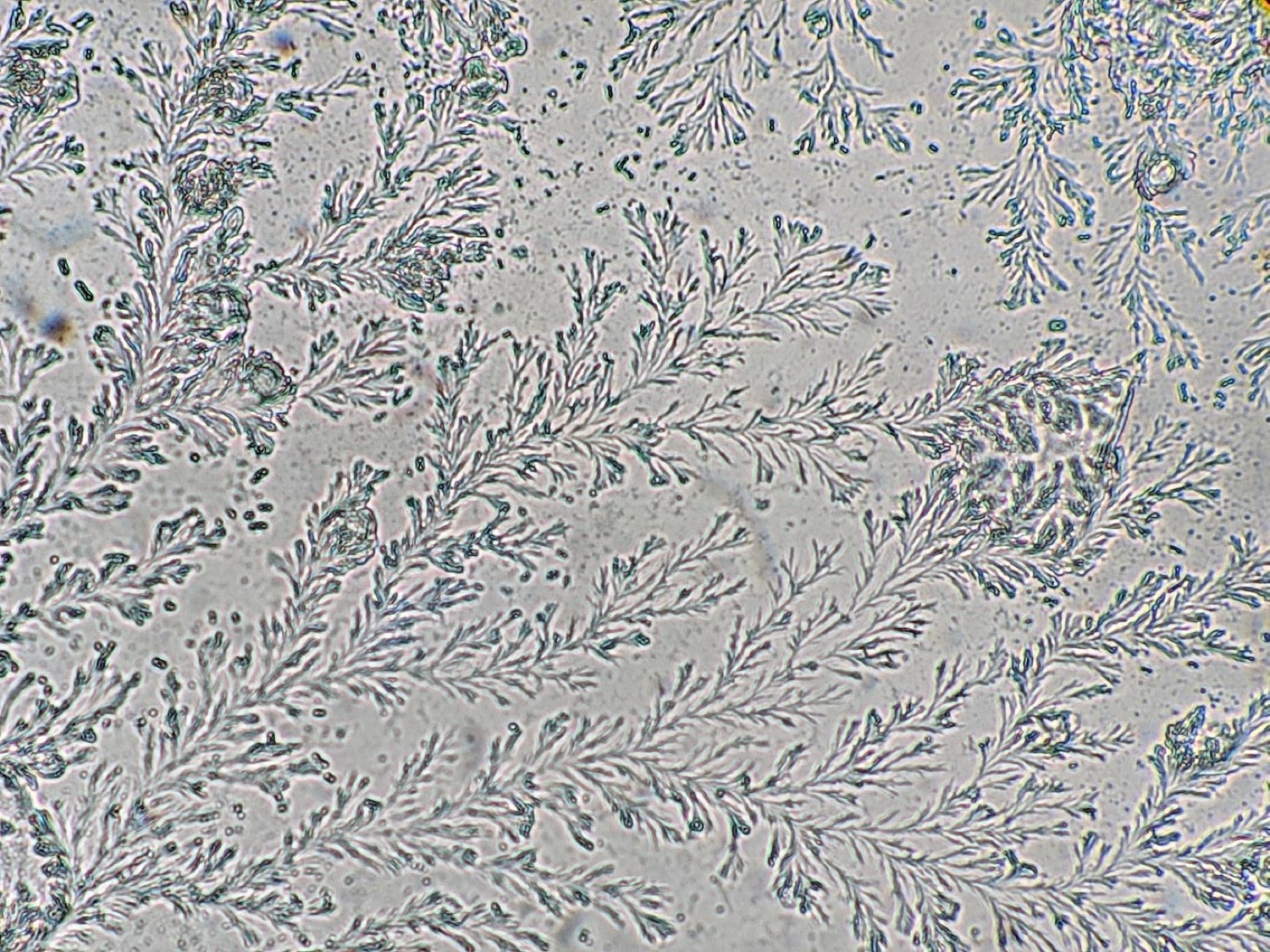

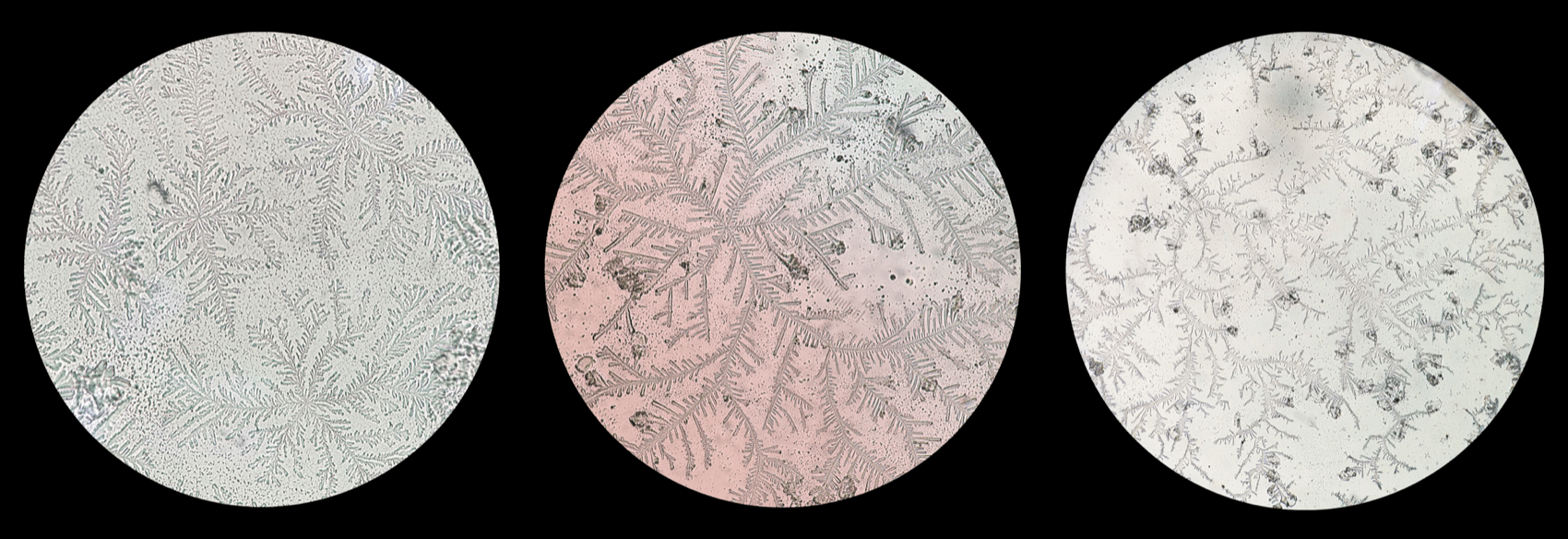

When Pilar Vigil peers through her microscope at the sight above, she feels like she’s swimming through a moonlit kelp garden.

“It’s like going under the sea,” says Vigil, an OBGYN and a professor at Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. “You see all these little stars and seaweed-like appearances.”

But this field of fractals is no underwater scene. It’s a microscopic view of mucus from the human cervix. These shapes are created during a “fern test,” named after the distinct fern leaf structures present in cervical mucus around ovulation.

In addition to being beautiful, cervical mucus is functionally important. It lines the cervix, vagina, and vulva, creating a protective barrier between the body and the environment. The mucus also plays a major role in fostering healthy bacteria, protecting from pathogens, helping sperm reach the reproductive tract, and even signaling disease and pregnancy issues to clinicians.

“It’s a gatekeeper,” explains Katharina Ribbeck, a biochemist at MIT who studies all kinds of mucus, including cervical mucus. “It lets the right things in and [keeps] the wrong things out.”

A fern test from a patient with recent membrane rupture. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

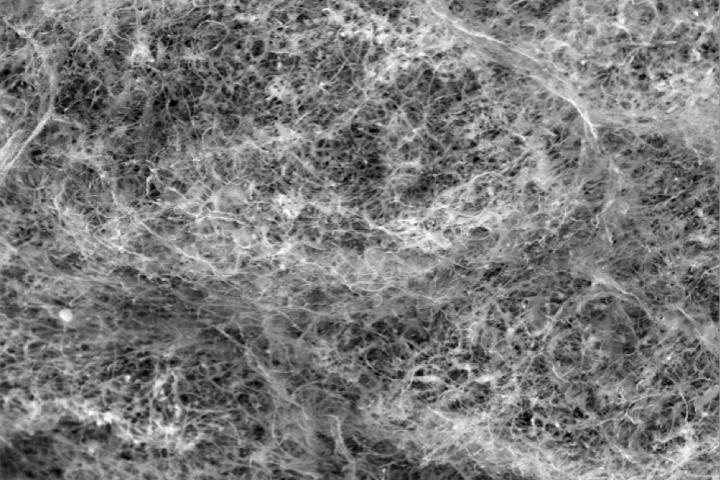

Cervical mucus, like other types of mucus, is a hydrogel made of approximately 90% to 98% water. It gets its viscous, jelly-like consistency from stringy molecules called mucins, explains Ribbeck.

“Imagine a pot of spaghetti, where the mucins are the spaghetti,” Ribbeck tells SciFri over the phone. “Those mucins entangle to build a network, a sponge that determines the makeup of the mucus.”

The makeup and physical properties of cervical mucus change with estrogen and progesterone hormone levels. Before ovulation or while taking certain hormone medications, higher levels of the estrogen hormone estradiol in the body increases the production of various types of mucins and changes water composition, Vigil explains.

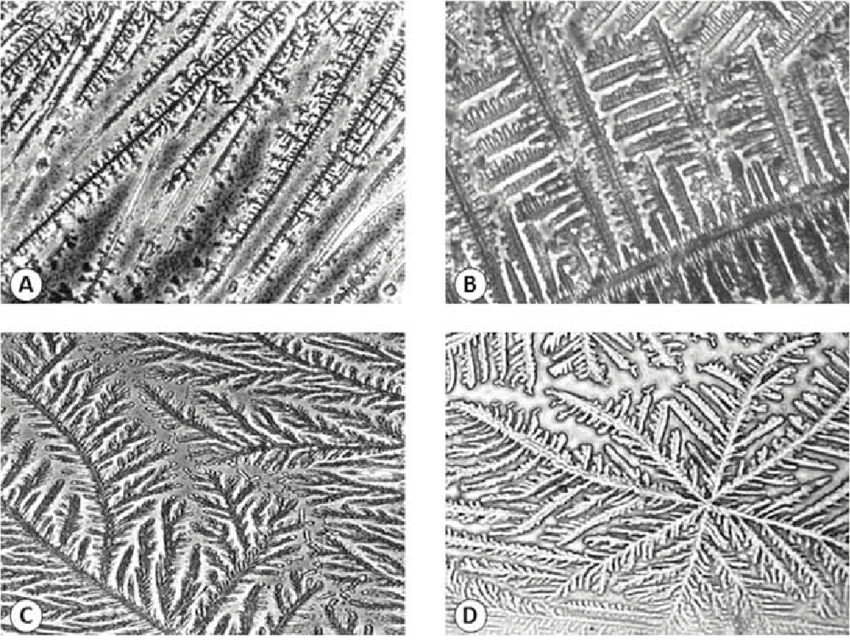

You can see the difference in consistency with your eyes, says Ribbeck. But the changes in ovulatory cervical mucus are even more apparent in a fern test.

When air-dried on a slide, and viewed through a microscope, the spaghetti strand-like mucins and other molecules aggregate into branching, fern leaf structures. The results of the fern test help doctors to confirm ovulation and also reveal lattices and trellises of complex beauty.

“You will get some lines, little stars as well, but the most predominant shape you are going to get is the ferning shape,” Vigil says. “So, before you ovulate you’ll get this beautiful ferning, and when ovulation has already occurred you will not find the ferning.”

These patterns will also appear in mucus if you are taking medication high in estradiol, she adds. It is a sign of healthy mucus, Pilar says.

“It’s important for people to know that cervical mucus is an important biomarker of ovulation, which is a good indication of health,” Vigil says.

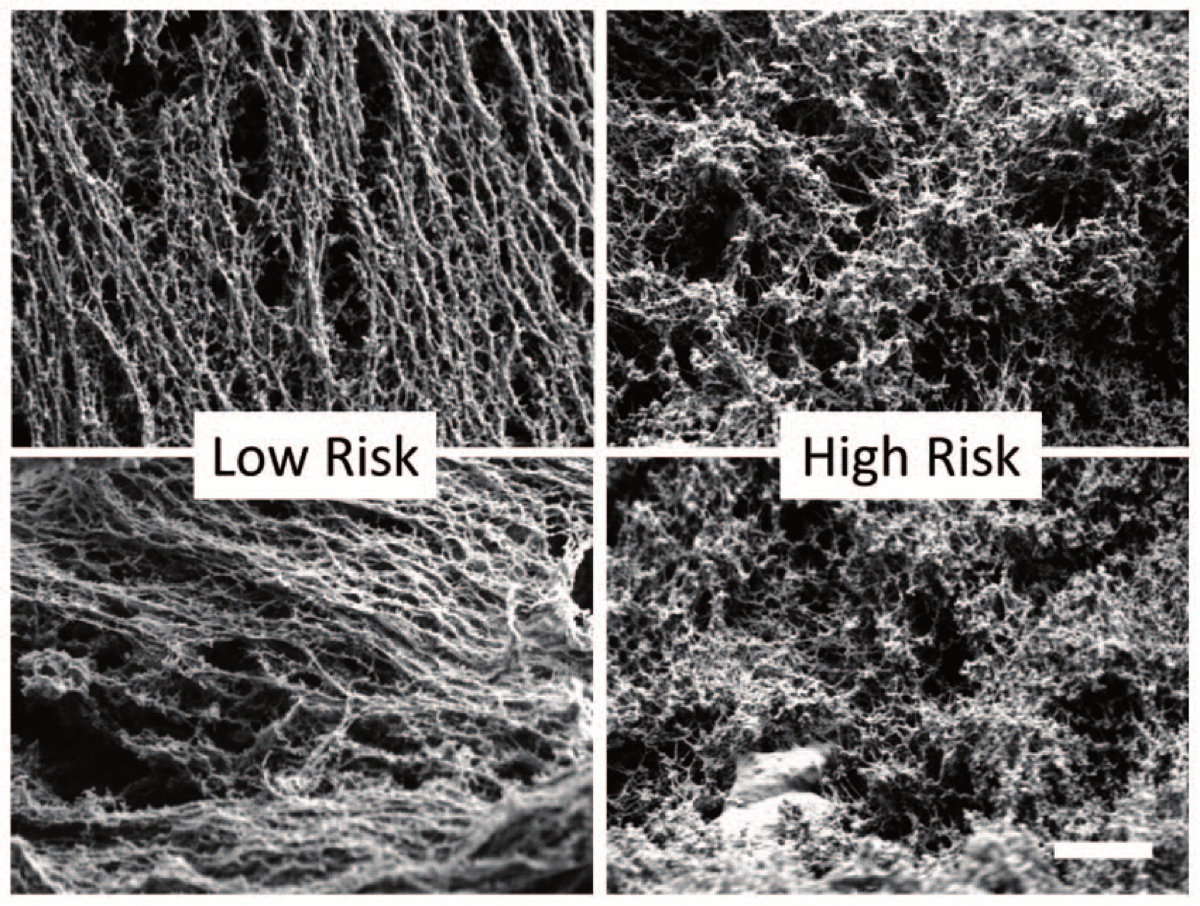

The cervical mucus created during ovulation is more permeable to help sperm pass through to the reproductive tract. This composition shifts during pregnancy, when the mucus produced is one of the thickest mucus arrangements that’s found, Ribbeck says. “That mucus is really the barrier between the outside world and the growing fetus. There’s no more skin, there’s no additional barriers.”

That mucus barrier can be essential to a baby’s health. Past research estimates between 25% and 40% of early births are caused by microbial infection in the uterus. This suggests that a barrier deficiency in cervical mucus could be one cause of preterm births, Ribbeck explains. In two studies, her team decided to further investigate the link.

In the 2017 study, Ribbeck tested if there was a difference in mucus permeability between patients who went into labor early and patients who gave birth after 37 weeks at full-term. Ribbeck ran small particles through cervical mucus samples taken from individuals at high risk for preterm birth and from individuals at the same stage in a healthy pregnancy.

She found that the mucus from those who had gone into preterm labor allowed particles to pass through more easily. The mucus properties were similar to what you find during ovulation, Ribbeck says.

“This was alarming because ovulatory mucus is mucus at its most permeable state,” Ribbeck says. Ovulatory mucus must be permeable for sperm, she says, but “if it happens during pregnancy, it’s also a potential window of opportunity for pathogens to pass through.”

“That mucus is really the barrier between the outside world and the growing fetus. There’s no more skin, there’s no additional barriers.”

Ribbeck and her team are still investigating what causes some individuals to produce the permeable mucus during pregnancy—whether the mucus is altered into a more susceptible state early on after conception, or if exposure to pathogens is damaging the barrier properties. In the future, she would like to see if cervical mucus can help predict if a pregnant person is at high risk of preterm labor by tracking these signatures early on. However, she notes that these studies are often difficult to conduct. “Imagine a [pregnant individual], who is already in distress, to donate cervical mucus.”

Now, her team is using these initial studies on cervical mucus to create tools that can be applied to other mucus in the body, like intestinal mucus to help earlier diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and other inflammatory bowel disease.

Three fern tests. Credit: Shutterstock

Cervical mucus is an incredible hydrogel of many purposes, with a beauty that often goes underappreciated, says Pilar Vigil.

“The first thing is to be able to see the beauty in the mucus, and then to be able to see how useful it is,” she says. “It’s really one of the most marvelous substances that you can find in our bodies.”

*Editor’s Note 7/19/2021: This article has been updated to reflect more inclusive language to other sexes in regards to health, pregnancy, and fertility. Learn more about why gender-affirming healthcare is essential in saving lives in a SciFri conversation with pediatric endocrinologist Kara Connelly and family therapist Alex Iantaffi.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.