How This Astronomer Discovered A New Type Of Galaxy

Burçin Mutlu-Pakdil talks how she got into astronomy and the path that led her to getting a new type of galaxy named after her.

Burçin Mutlu-Pakdil. Credit: Science Friday

This article by Brittney G. Borowiec was originally published on Massive Science. The story is a part of Breakthrough, a short film anthology from Science Friday and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) that follows women working at the forefront of their fields. Learn more and watch the films on the Breakthrough spotlight page.

Astrophysicist Burçin Mutlu-Pakdil discovered a new type of galaxy while working on her PhD at the University of Minnesota. She investigates the smallest and faintest galaxies in the universe, and how dark matter has shaped them. When not peering deep into space, she advocates for women and other equity-seeking groups in science. Mutlu-Pakdil has received several commendations, including postdoctoral fellowships from the NSF and the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics, TED Fellow and Senior Fellow awards, and an AAAS IF/THEN Ambassador award. In this Q&A, we talk about what it’s like to discover a new type of galaxy, traveling, her advice for future Galaxy Hunters, and more.

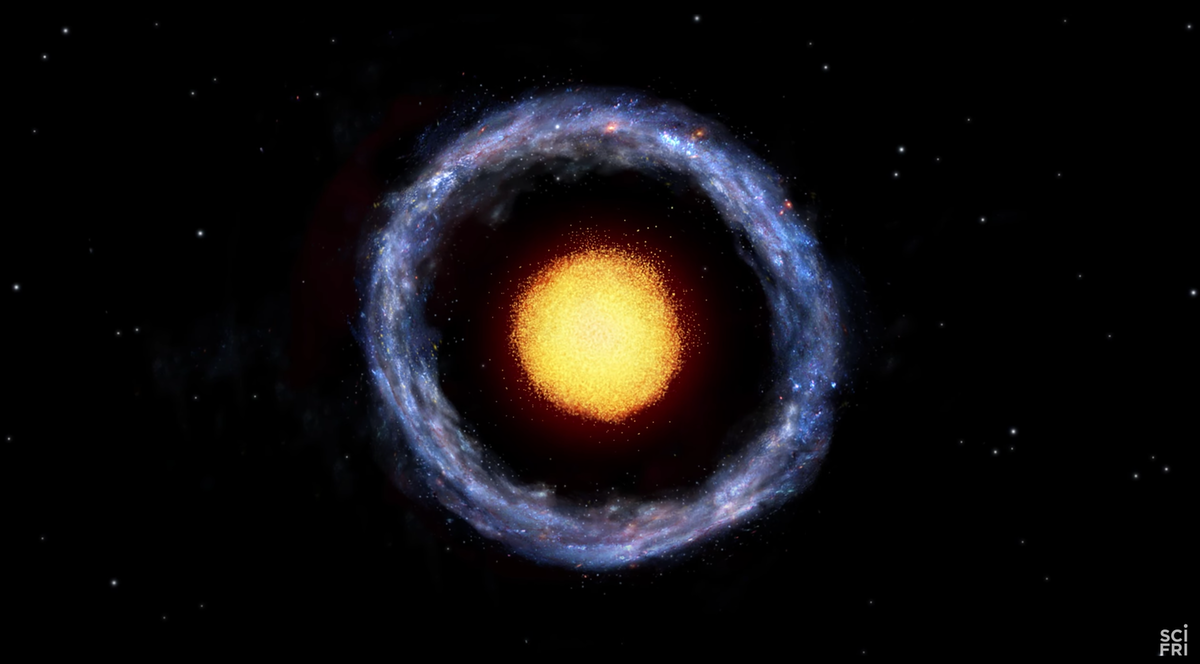

Burçin’s Galaxy. Credit: Science Friday

So, what is dark matter, exactly? Because I feel like that’s something that people throw out a lot, but not a lot of people actually understand what that is.

[laughs] It is a good question, and we are trying to figure it out!

So when we observe, for example, galaxies and how stars are moving around, we expect stars at the edge [of the galaxy] to move much slower. But then when we observe them carefully, we see that they have a certain velocity [that] we cannot explain, if it is [composed of] only the normal matter that we know. There must be another matter that makes [the stars] move in that certain way. And we think that this is dark matter.

We cannot observe it with any instrument. We can understand or study it through its effect on normal matter. So we know that it there.

The smallest and faintest galaxies can give us a unique perspective about their nature, because they are more dark matter systems. They are unlike the Milky Way, where there are billions of stars, and these stars interact, so there are so many physics involved. So, understanding the effect of dark matter becomes a bit harder to disentangle. But in these [small and faint galaxy] systems, there are only a handful of stars. So most of the effect comes from dark matter, and we can really understand how the galaxy evolved with the effect of dark matter.

So, when you say “observing,” take me through what your typical day is. So, You’ve got an observation, what are you going to do that day? What’s that look like?

So since I am trying to find the faintest systems, the telescopes we are using are not small. They are like six meter, four meter, eight meter telescopes, and the Hubble Space Telescope. All these telescopes, since they are big, they are hard to get time on. So [members of] the astronomy community are constantly asked for more observing time, but we have just handful of telescopes for that each year.

There are several calls for astronomers to present their science goals. And from those [proposals], a handful of lucky astronomers will get the time to take the data. Some of the telescopes let you to observe in remote observing stations. So, you basically go to the next office and control the telescope in Chile. But some of the telescopes require you to be there, on the mountain, and you need to fly all the way to Chile. Maybe you have just one night, you’ll go there just for one night and observe, and come back.

That’s amazing. I didn’t realize how hard it is to get access to a telescope. I mean, it’s great, it means there’s a lot of really good science, but wow, you have to basically write a grant before you can even [access your equipment].

Exactly! There are amazing science goals, but there are only a handful of telescopes. So they are just trying to really pick which can lead to quick results, which can lead to very important scientific results, so they decide based on that. So that’s actually one of the common stereotypes about astronomers. My friends generally say, “Okay, I will visit you! Would you take me to the telescopes and observe stuff together?” I’m saying, “Oh, no, I don’t have the luxury to just go to the telescopes and observe anywhere.”

You write about how you don’t want to blend in, you want to stand out, you’ve fought against stereotypes and worked hard, you want to live beyond labels. Can you maybe reflect on that a little bit?

Society had so many labels, so many categories [for me]: a daughter, a women, a scientist, a Muslim, an immigrant, a married woman. Society expects you to follow certain paths. And sometimes people can have different identities that clash with these societal norms, and it just makes it super hard to survive in the existing norms.

One example is [when] I chose astronomy and physics as my job. The first reaction that I got in Turkey was, “You are a woman, you will not find any jobs, you will just be a teacher. You will not be able to do science, it’s all men. You will not be able to survive; you will be alone.” These were my relatives and my friends. I didn’t listen to them. I said, “Okay, whatever. This is your view. This is not me, and I don’t fit your own experience.”

First day of orientation [in university], a faculty member came to me and said, “You moved to [the comparatively small city of] Ankara [from Istanbul]? You are coming here, you are a woman, and you are you want to study physics. Are you crazy?!”My very existence is questioned because I chose physics. That’s all that I did.

I realized that all these perceptions are coming from their own views, their limited views. This cannot reflect on my own personal experience. At the time, there was a hijab ban, and any [woman who wore a hijab] couldn’t go to any government or educational facilities. That meant that I couldn’t get an education if I wanted to live my own identity. It really alienates you; it puts you in a different box, and I hated it. I just wanted to be myself, and that really affected my choice to come to the United States. I just wanted to do science, and I just wanted to live my own identity. Coming [to the United States], people generally say, “Okay, what is the biggest cultural shock for you?” I say, “Okay there are, of course, many cultural shocks, but at least I can live my own identity.”

That’s a big thing. I am relieved. At least I feel like myself. Coming here, being a Muslim, [working] in a foreign language, of course has challenges. For example, at [certain] scientific conferences, women are more likely to get questions about their credentials, like, “Did you study this? Did you check this data set too? Are you sure about that result?” For men, it is more like, “what is your next step? That is so unique!” The difference is so obvious.

If I tried to follow their path, I wouldn’t be happy. This life is too short to follow other’s views. So in the end, I said, “Nevermind, I don’t care what you think about me. I am me. So I will live my life.”

What would you say to someone in high school or middle school thinking about going to science?

There are many other identities who go through similar experiences, and you can form and support each other.

And the other thing is, if you decide to quit, don’t criticize yourself, and say that you are a failure. Instead, society failed you. They couldn’t welcome you. I feel like sometimes we are constantly saying to the young generation, “If you believe you, will reach [your goals]!” Of course you can reach [your goals], but if you don’t reach them, it is not because you are not clever, or a genius, or hard working, or that you don’t deserve it. It is because in society is still there so many things to work on.

I want to finish off by asking, is there anything else you want people to know, anything else you want to talk about?

I want to emphasize to find a support system. We generally feel like we are the only one going through these experiences, but although [member of your support system] might not go through the exact experience with you, they will have a sense about the hardship. Having these support systems is really important. If you are in an academic environment, you can reach out to the faculty, there are several associations for students. Just reach out. Even if the university doesn’t have [a support system for you] in your local environment, through social media just try to find the people that you click with. So you can share your experience and motivate each other, and in the end uplift each other. I think this is really important, and I really wish someone have given me that advice when I was young.

Watch Breakthrough, a short film anthology that follows women working at the forefront of their fields.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Brittney G. Borowiec is a postdoctoral fellow at Wilfrid Laurier University, where she studies how lamprey-specific pesticides damage fish mitochondria. During her PhD at McMaster University, she studied how killifish cope with periods of low oxygen. Outside the lab, she’s a science writer with work appearing in Nature, PBS Eons, The Conversation, the Canadian Science Publishing Blog, Massive Science, and elsewhere.