Robin Wall Kimmerer Wants To Extend The Grammar Of Animacy

How our scientific perspective of a bay changes when language frames it as a verb—to be a bay—instead of a noun.

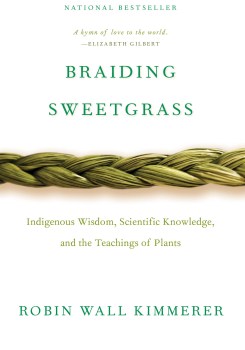

The following is an excerpt from of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Disclaimer: When you purchase products through the Bookshop.org link on this page, Science Friday may earn a small commission which helps support our journalism.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants

My sister’s gift to me one Christmas was a set of magnetic tiles for the refrigerator in Ojibwe, or Anishinabemowin, a language closely related to Potawatomi. I spread them out on my kitchen table looking for familiar words, but the more I looked, the more worried I got. Among the hundred or more tiles, there was but a single word that I recognized: megwech, thank you. The small feeling of accomplishment from months of study evaporated in a moment.

I remember paging through the Ojibwe dictionary she sent, trying to decipher the tiles, but the spellings didn’t always match and the print was too small and there are way too many variations on a single word and I was feeling that this was just way too hard. The threads in my brain knotted and the harder I tried, the tighter they became. Pages blurred and my eyes settled on a word—a verb, of course: “to be a Saturday.” Pfft! I threw down the book. Since when is Saturday a verb? Everyone knows it’s a noun. I grabbed the dictionary and flipped more pages and all kinds of things seemed to be verbs: “to be a hill,” “to be red,” “to be a long sandy stretch of beach,” and then my finger rested on wiikwegamaa: “to be a bay.” “Ridiculous!” I ranted in my head. “There is no reason to make it so complicated. No wonder no one speaks it. A cumbersome language, impossible to learn, and more than that, it’s all wrong. A bay is most definitely a person, place, or thing—a noun and not a verb.” I was ready to give up. I’d learned a few words, done my duty to the language that was taken from my grandfather. Oh, the ghosts of the missionaries in the boarding schools must have been rubbing their hands in glee at my frustration. “She’s going to surrender,” they said.

And then I swear I heard the zap of synapses firing. An electric current sizzled down my arm and through my finger, and practically scorched the page where that one word lay. In that moment I could smell the water of the bay, watch it rock against the shore and hear it sift onto the sand. A bay is a noun only if water is dead. When bay is a noun, it is defined by humans, trapped between its shores and contained by the word. But the verb wiikwegamaa—to be a bay—releases the water from bondage and lets it live. “To be a bay” holds the wonder that, for this moment, the living water has decided to shelter itself between these shores, conversing with cedar roots and a flock of baby mergansers. Because it could do otherwise—become a stream or an ocean or a waterfall, and there are verbs for that, too. To be a hill, to be a sandy beach, to be a Saturday, all are possible verbs in a world where everything is alive. Water, land, and even a day, the language a mirror for seeing the animacy of the world, the life that pulses through all things, through pines and nuthatches and mushrooms. This is the language I hear in the woods; this is the language that lets us speak of what wells up all around us. And the vestiges of boarding schools, the soap-wielding missionary wraiths, hang their heads in defeat.

This is the grammar of animacy. Imagine seeing your grandmother standing at the stove in her apron and then saying of her, “Look, it is making soup. It has gray hair.” We might snicker at such a mistake, but we also recoil from it. In English, we never refer to a member of our family, or indeed to any person, as it. That would be a profound act of disrespect. It robs a person of selfhood and kinship, reducing a person to a mere thing. So it is that in Potawatomi and most other indigenous languages, we use the same words to address the living world as we use for our family. Because they are our family.

To whom does our language extend the grammar of animacy? Naturally, plants and animals are animate, but as I learn, I am discovering that the Potawatomi understanding of what it means to be animate diverges from the list of attributes of living beings we all learned in Biology 101. In Potawatomi 101, rocks are animate, as are mountains and water and fire and places. Beings that are imbued with spirit, our sacred medicines, our songs, drums, and even stories, are all animate. The list of the inanimate seems to be smaller, filled with objects that are made by people. Of an inanimate being, like a table, we say, “What is it?” And we answer Dopwen yewe. Table it is. But of apple, we must say, “Who is that being?” And reply Mshimin yawe. Apple that being is.

Yawe—the animate to be. I am, you are, s/he is. To speak of those possessed with life and spirit we must say yawe. By what linguistic confluence do Yahweh of the Old Testament and yawe of the New World both fall from the mouths of the reverent? Isn’t this just what it means, to be, to have the breath of life within, to be the offspring of Creation? The language reminds us, in every sentence, of our kinship with all of the animate world.

English doesn’t give us many tools for incorporating respect for animacy. In English, you are either a human or a thing. Our grammar boxes us in by the choice of reducing a nonhuman being to an it, or it must be gendered, inappropriately, as a he or a she. Where are our words for the simple existence of another living being? Where is our yawe? My friend Michael Nelson, an ethicist who thinks a great deal about moral inclusion, told me about a woman he knows, a field biologist whose work is among other-than-humans. Most of her companions are not two-legged, and so her language has shifted to accommodate her relationships. She kneels along the trail to inspect a set of moose tracks, saying, “Someone’s already been this way this morning.” “Someone is in my hat,” she says, shaking out a deerfly. Someone, not something.

When I am in the woods with my students, teaching them the gifts of plants and how to call them by name, I try to be mindful of my language, to be bilingual between the lexicon of science and the grammar of animacy. Although they still have to learn scientific roles and Latin names, I hope I am also teaching them to know the world as a neighborhood of nonhuman residents, to know that, as ecotheologian Thomas Berry has written, “we must say of the universe that it is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.”

From Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013). Copyright © 2013 by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Reprinted with permission from Milkweed Editions. milkweed.org.

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a mother, scientist, decorated professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. She is the author of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants, which has earned Kimmerer wide acclaim. Kimmerer lives in Syracuse, New York, where she is a SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental Biology, and the founder and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment.