This Biotech Artist Wants Scientists To Think About Their Creations

Artist Ani Liu challenges how we think about creating the future, using artificial intelligence and mind-controlled sperm.

In 2015, artist Ani Liu heard two sentences that changed her entire approach to art: “Digital is dead. Bio is the new digital.” Those words, spoken at a welcome talk on her first day as a grad student at the MIT Media Lab, triggered panic at first. “I was like, oh shit, I don’t know anything about biology,” Liu says.

But today, biology is the starting point for most of Liu’s work. Her feminist artworks are visceral, thought-provoking, and anchored in biotechnology. “I like to say that I have a research-based practice,” Liu says. “Each of the artworks I make are usually centered around a specific topic that I do a deep dive of research into.”

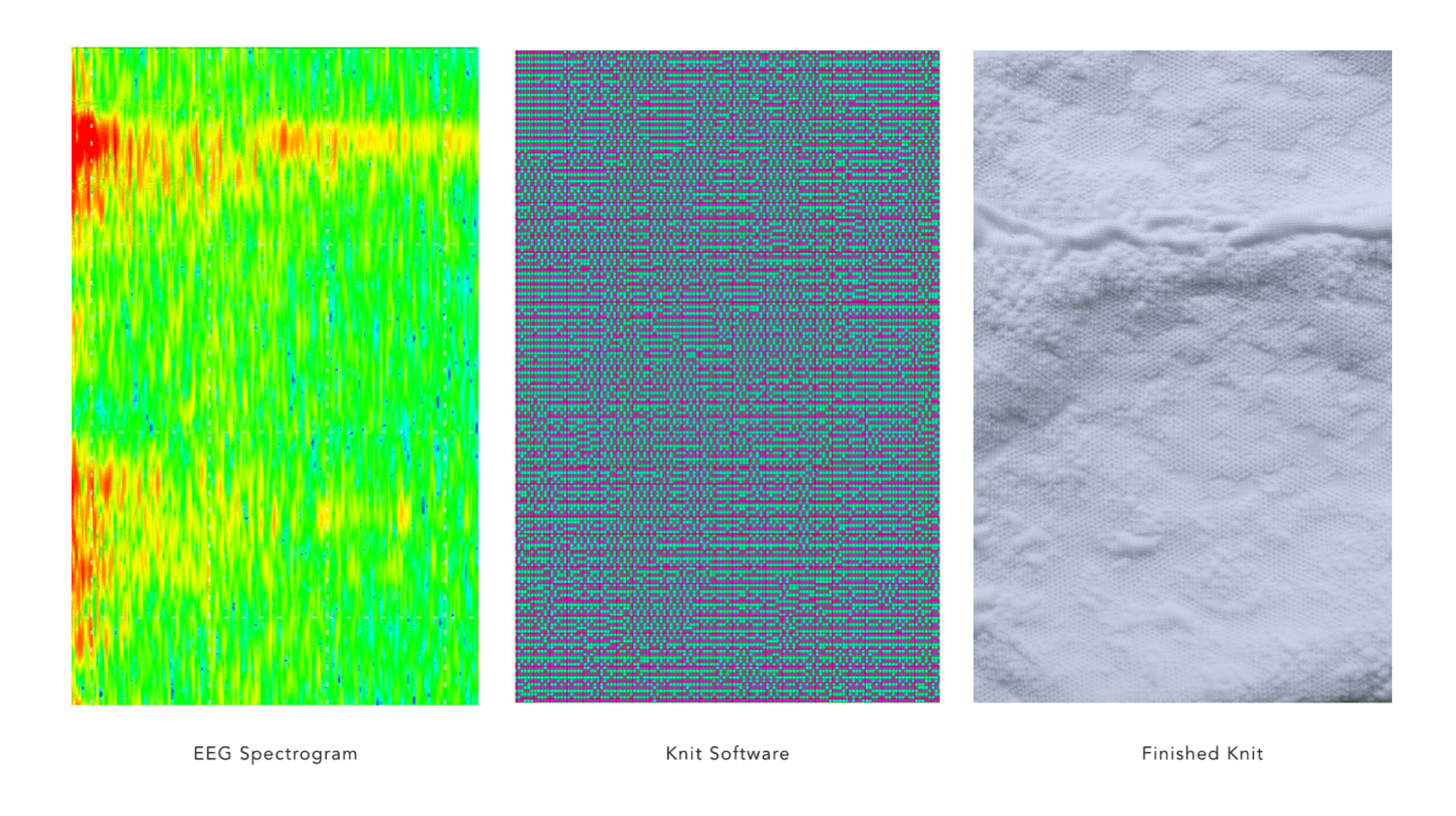

Her body of work is executed through experimentation: She’s used organic chemistry to concoct perfumes that smell like people emotionally close to her; she’s programmed a knitting machine to produce a garment worker’s brain signals; she’s engineered a device that enables the wearer to control the direction of swimming sperm with their mind.

The throughline of her work is speculative design, an approach to art and design that critiques larger societal issues. Speculative design isn’t about predicting the future, Liu clarifies. “It’s different ways of considering the future, and hopefully, they’re actionable. But for me, it’s the importance of letting things outside of capitalism drive progress.”

Her pieces provide a moment to pause. “One of the things that I find so important about speculative design is that it allows people to reflect on the implications of the technologies that we consume, instead of kind of blindly going along with it,” Liu says. “I feel like it forces us to unpack what is going on.”

Credit: D Peterschmidt

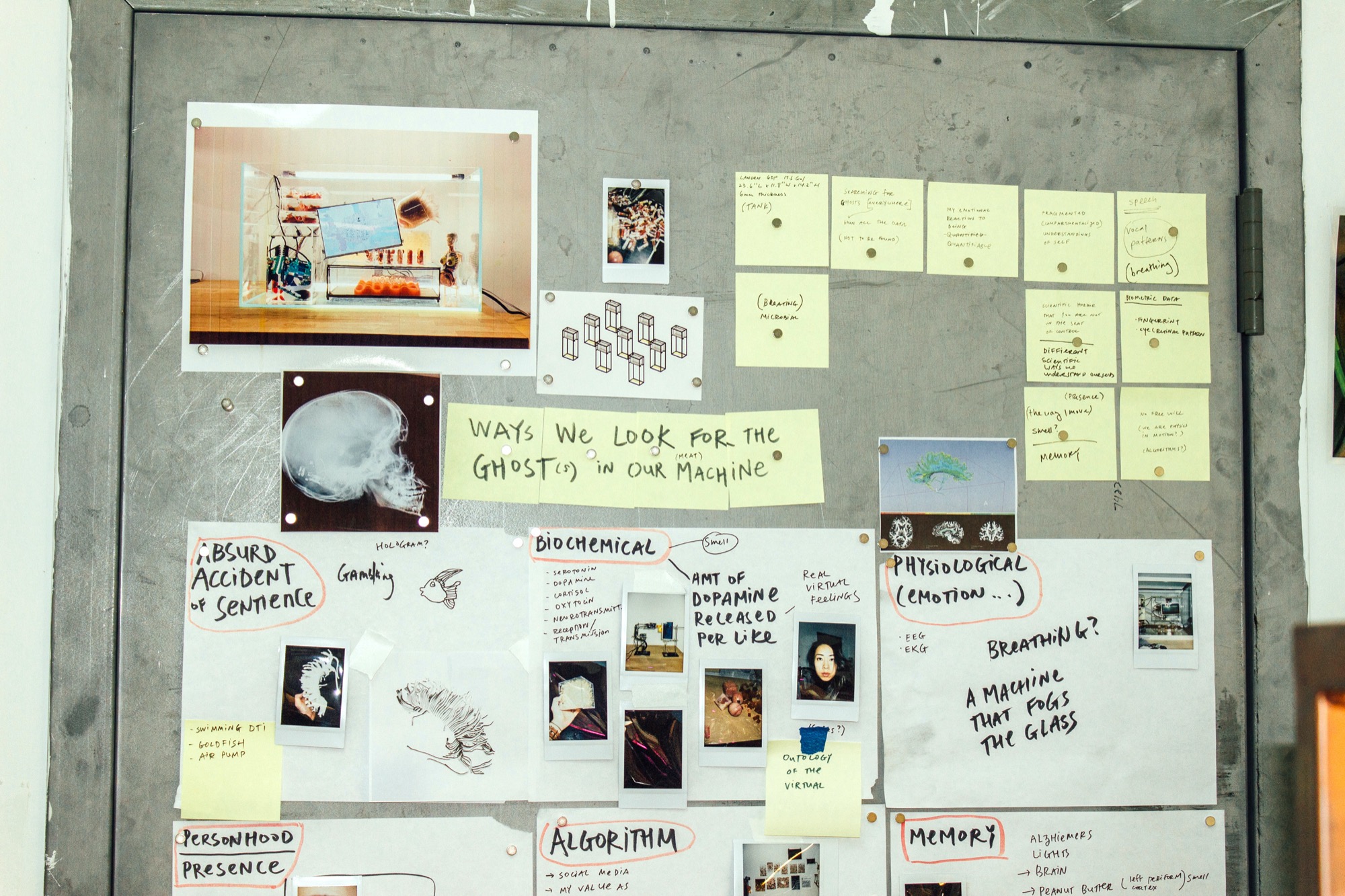

Liu’s workspace in Long Island City, New York has more in common with a scientific lab than it does a traditional art studio. Jars of organic matter, electrodes, and machines are strewn across her desk and shelves. Tucked in one corner, a tank filled with circuits and electrodes sits leftover from her “Real Virtual Feelings“ project.

Liu points to a two-foot-tall clear tube of stringy, sinew suspended in a pus-like liquid. She wanted to create an iteration of a self-portrait, based on the materials in her body. She even worked with a radiologist who helped her take scans of her body to figure out the percentages of water, fats, and different kinds of proteins, “to try to show a portrait of myself as a kind of stratified tube of goop,” she explains. But, she found the organic soup wasn’t very stable. “Some of the prototypes I would make would start to [let] off gas, they weren’t sterile. Sometimes they would explode,” she laughs.

Like the explosive mixture of those early prototypes, Liu didn’t mix well with science and math at first. “At some point early on, an authority figure told me that girls are bad at math,” she says. “And it really sunk deep into me. For most of my life, I felt so intimidated by laboratories and science and technology.”

That changed when she decided to approach art with materials that required math, science, and technology. “I was like, oh, I’m not that bad at circuit making, or this isn’t actually outside my realm of possibility. It wasn’t until I used it as a secondary tool that it really felt natural.”

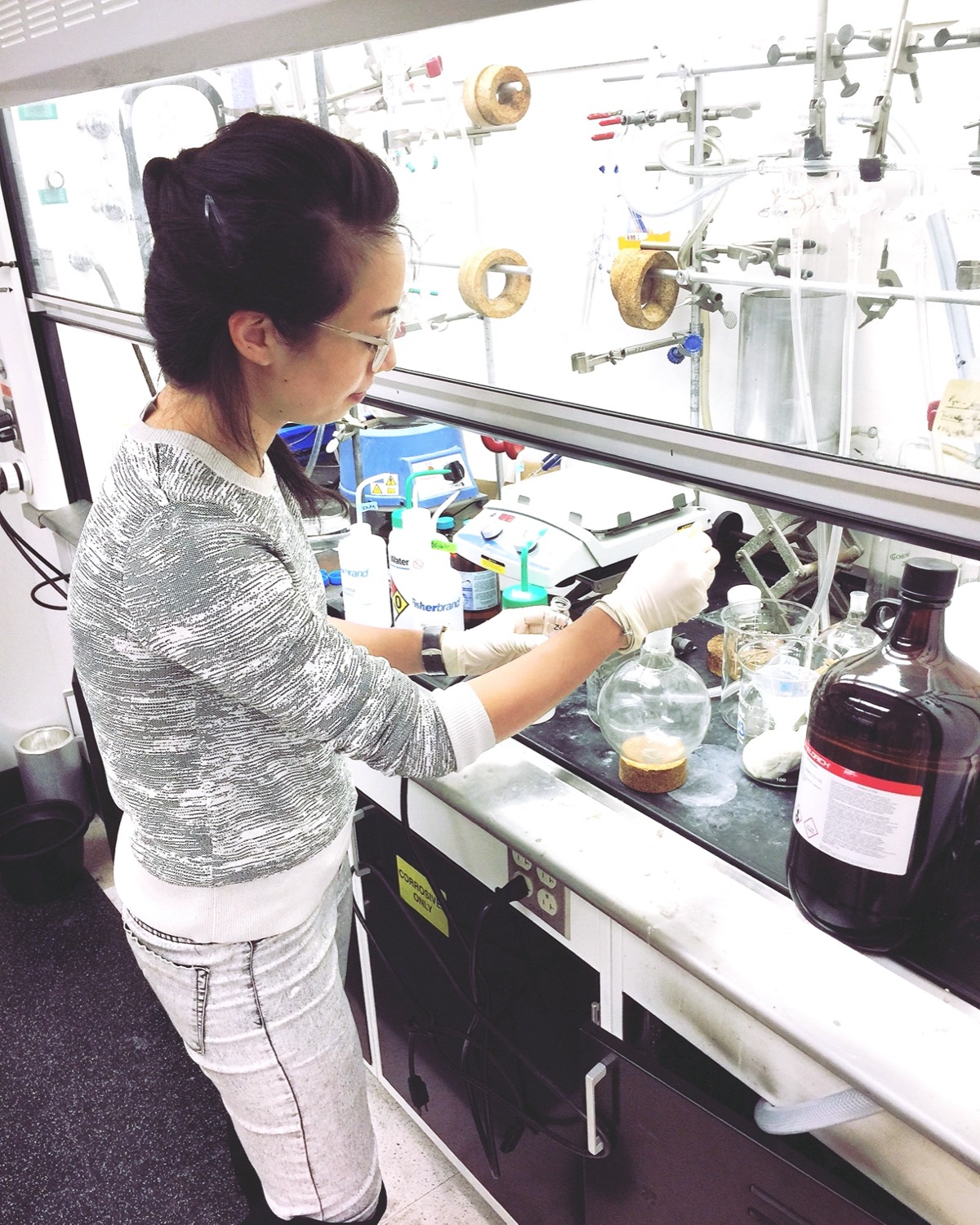

After attending Dartmouth College and Harvard University, Liu dove headfirst into biology-infused art at the MIT Media Lab. She transformed her dorm room into a mini-lab space, purchasing distillation equipment, glassware, an incubator, and microscope on eBay. She also worked out a deal with some professors to get access to labs at night when they weren’t in use, so she could try out personal experiments, like genetically altering a plant’s smell into a human scent.

Smell intrigued Liu so much that she created multiple perfumes that smelled like her husband—a kind of “scent portrait” made from intimate and heated moments, like after a fight or showering, or before saying goodbye.

“When you paint a portrait of someone, there’s not just one reality of how someone looks or appears,” she says. “So I wanted to make many layers of portraits of him.”

Liu compared the process of creating the piece to being a forensic scientist. “You’re like a detective. You have the evidence and then you have to go backwards.” Since they were long distance, Liu gave her husband special bags to send his dirty, stinky shirts so she could begin the distillation process. She ran them through a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry machine to identify some of the chemicals that were coming from the shirt. Then, she would apply different solvents, like chloroform and ethanol, to capture the most volatile organic compounds—the signature molecules responsible for the smell.

Those “little chemical portraits” resulted in three different perfumes of her husband. “I personally deeply think [it smelled like him],” she says. “But smell is super subjective. My husband thinks it smells like his brothers. And his brothers think that it smells like him, which is to say that smells really bad,” she laughs.

Human perfume bottles. Credit: Ani Liu

Since then, Liu dove into other fields for inspiration. A few years ago, she learned that two researchers from Stanford programmed a chip with a paramecium on top, and used it to play Pong. Since paramecium are susceptible to an electric field, the researchers were able to control their movement and hit the game’s Pong ball in a desired direction by changing which way the field was flowing. “My whole mind exploded because I thought it was so interesting,” Liu says. “It was like a lightning bolt hit me in the class, because I was like, ‘What if that thing was a sperm instead?’”

Sperm are also susceptible to an electric field, and Liu thought similar techniques from the Stanford study could also be used on them for an art piece.

After some research, Liu found an EEG device that could be trained to recognize specific patterns of brain signals. For example, if the wearer repeatedly thinks “left, left, left,” the EEG can assign those “left” brain signal patterns to a certain action, like moving an object left. In this case, that object was sperm. “It was fairly simple,” she says. “I created a little circuit on a glass slide. And it created an electric field where I would switch the polarity back and forth. And they would swim towards it.”

Originally, Liu wanted the commanding brain signals to be related to complex concepts; thinking of free will would orient the sperm left or female empowerment would turn it right, for example. But that ended up being too abstract for the EEG machine to learn quickly and too difficult to get consistent results from person to person. She settled on attention, relaxation, and other signals that are easy and quick to train.

Beyond the technical feat of the project, the piece touches on something greater. “What if a woman was controlling it? And what does this mean symbolically and metaphorically as a performance?” By allowing female participants to physically control sperm, the piece allows them to control an aspect of male bodies—a flip on the generations of society’s control over female bodies, such as the regulation of contraceptives and genital mutilation.

All of Liu’s art explores the human nature of discovery—the jubilations and pitfalls. “In order to do high-level work in a laboratory, you have to be very intensely focused. Like, I’ve met some individuals that have spent most of their life investigating several molecules,” she says. “But I think we should demand it of our researchers to do a deep dive and then zoom out, a back and forth. And I feel like that’s what I do all the time.”

The door in Liu's studio. Credit: D Peterschmidt

It’s that zooming in and out that has led Liu to classify her designs as “speculative realism,” similar to how Margaret Atwood describes her writing as speculative fiction, as opposed to science fiction. “Some amazing sci-fi and a lot of art can prime what you think reality should or could be,” she says. For example, robots portrayed in movies and TV, such as the nanny robot Rosie in The Jetsons and the murderous robot in The Terminator, pigeon-holed humans’ relationships to robots, Liu says, and over time, fiction can influence reality. She points out how today we have female-voiced AI assistants, which imply an outdated gender stereotype of nurturing, an unconscious callback to Rosie.

“Slowly over time, I think it can really impact reality. That relationship between speculation and reality, I think it’s very important,” she says. “There’s a lot of room for interpretation and [many directions] that the research or technology development can go.”

“I think we should demand it of our researchers to do a deep dive and then zoom out, a back and forth. And I feel like that’s what I do all the time.”

And having an array of perspectives can help more people connect with complex aspects of research.

“A big part of the importance of speculation is allowing multiple voices into the conversation. Because what’s better for me or what’s better for my daughter or what’s better for someone living on a reservation might be very different,” Liu says. “So, I think that there’s a really important seat at the table for artists and designers.”

Liu hopes that her speculative work loops back around to the scientists who inspired it in the first place—widening the view on research. “I hope that they consume these types of media and artworks so that they really think about the non-intended, secondary implications of these technologies,” she says. “It is my near and dear hope and dream that it will cause whoever views it—scientists and owners of big corporate technology institutions—to really think about what is happening.”

Ani Liu. Credit: D Peterschmidt

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.