Artists And Chefs Are Putting Ecological Crises On The Menu

Projects like “last suppers” with climate-threatened ingredients and picnics with AI-assisted recipes contemplate our food futures.

Foods served at a "Mock Wild" picnic by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy. Credit: Genomic Gastronomy

Zack Denfeld wants to give you a taste of the future, and he’s doing it with pollution-filled cookies and barbecue sauce made with ingredients from radiation-bred crops.

Denfeld and artist Cathrine Kramer are co-founders of the Center for Genomic Gastronomy, an artist think tank started in 2010 that envisions the futures of food—biodiversity loss, lab-grown innovations, ethical controversies, and all.

Based in Amsterdam and Portugal, the group collaborates with scientists, farmers, hackers, and chefs on edible creations that showcase how future food systems might work and what they might taste like.

“One of the reasons we like to work with food is that it’s experiential,” Denfeld says. “You have to put something into your body and all of a sudden, your brain kicks in and you start being much more critical of things.”

Artists are increasingly confronting global environmental crises, but those who use food have the uniquely visceral opportunity to make abstract issues ingestible, and sometimes tasty. These projects often aim to shed light on new or unconsidered angles of existential crises and to spark conversations about the positive and negative consequences of our food and ecosystem choices today.

For its latest project, the Genomic Gastronomy team is blending an ancient farming concept with artificial intelligence (AI). They’ve partnered with a few Netherlands-based food forests, which are agricultural production centers that mimic forest ecosystems. Unlike on conventional farms, plants in food forests grow in interspersed layers. Taller trees, often fruit or nut varieties, create canopy and mulch for smaller food-producing trees, vines, shrubs, and root crops, some or which aren’t available in grocery stores, like yarrow and daylily leaves.

Food forests don’t require the same level of pesticides or maintenance as farms do, but they’re much smaller than large-scale conventional farms, produce less protein by comparison, and are less predictable: What crops can be harvested, and how much, can change from day to day.

Denfeld’s team is using AI to help. Their project, called “MVP x FFF”—short for Minimum Viable Proteins x Food Forest Flavours—uses AI that incorporates culinary information on rare cultivars to create new recipes that combine ingredients available that day in nearby food forests with commercially available, meat-free protein alternatives, like plant-based egg substitutes or pasta made from beetle larvae.

“What does it look like if we bring together this highly industrialized protein production industry with this really inefficient, but super resilient food forest agricultural typology on a plate?” says Emma Dorothy Conley, an artist, designer, and producer at the Center for Genomic Gastronomy. “Ingredients available change, like every two weeks … How can people become better cooks to be able to manage that kind of change and dynamicism?”

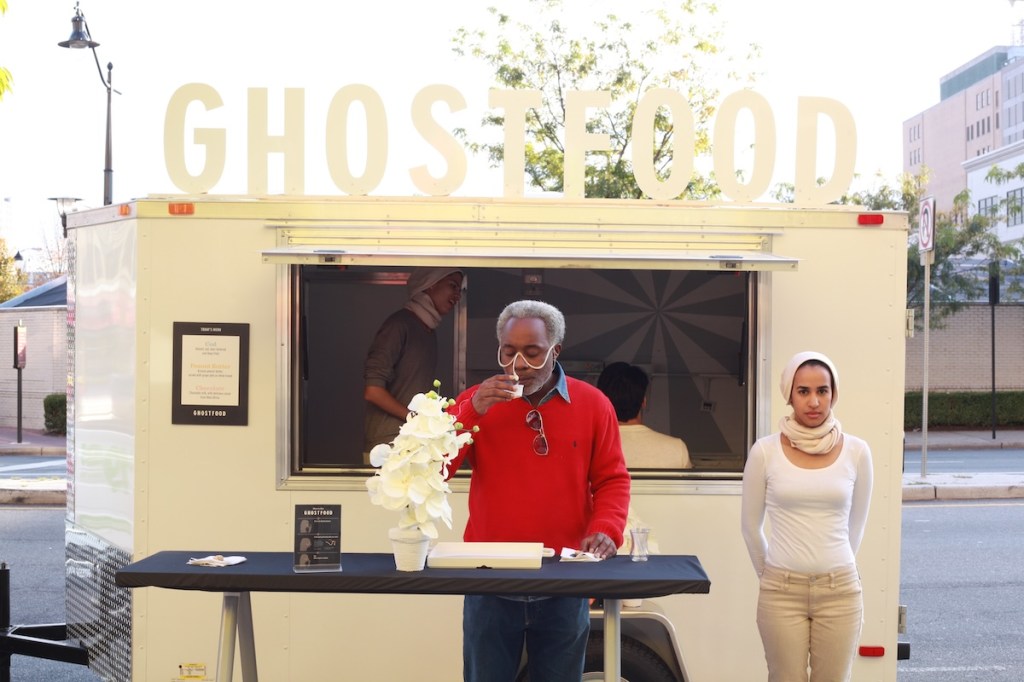

AI concoctions aren’t necessarily yummy—a disclaimer in this video says that all recipes are a “lucid hallucination” and “cannot be held accountable for bad taste, being nutritionally deficient, or even poisonous.” But the Genomic Gastronomy team has used the system to throw “Mock Wild” picnics and taste tests that include AI-assisted, human-vetted dishes, like pine tree pesto pasta that incorporates spruce tops and sweet chestnuts.

“Mock Wild” events are just one potential future imagined by the Genomic Gastronomy team. In other projects, adventurous eaters have compared cookies and egg foam meringues made with air that contains actual smog from different cities worldwide. They’ve even become the restaurant themselves by contributing their tears and dead skin cells for organisms that feed on humans.

“Our goal is not to market something or to bring an ideology to bear, but to create a moment when people feel those futures or experience those strange realities today and then parse through with others how they feel about them,” Denfeld says.

Restaurants are also putting existential threats on the plate. Chefs and food activists worldwide have long championed local, indigenous ingredients and sustainable eating, but as global warming and biodiversity loss break new records, an increasing number are using their kitchens to send explicit messages.

Some are creating dishes that showcase flavors facing extinction. Former White House chef Sam Kass, for example, throws “Last Suppers,” or “last-in-a-lifetime” educational meals that highlight chocolate, seafood, and other ingredients that are projected to die out, change flavor, or become inaccessibly expensive as Earth warms. Others are focusing on ingredients that are all too available by putting invasive species on their menus. (Scientists are teaching home chefs to do the same through resources like EatTheInvaders.org and events like the Institute for Applied Ecology’s annual Invasive Species Cook-Off.)

The food service industry is also leaning in. Earlier this year, the James Beard Foundation announced a chef-led education and advocacy campaign to push for federal climate policies and, in partnership with George Washington University’s Global Food Institute, released a report that details how climate change impacts independent restaurants.

Turning education into action isn’t easy, says Dr. Francesco Sottile, an agronomist at the University of Palermo in Italy. Sottile is part of Ark of Taste, an initiative that’s cataloged over 6,300 wild species, food products, and culinary traditions that face extinction worldwide. Their catalog includes entries ranging from honey from the mountains of Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province to Witchetty grubs eaten raw or roasted in Central Australia.

“It’s hard to let people understand how the agro-industrial system has been the cause of [much] of the climate crisis we are facing,” Sottile says. “Biodiversity must be not just a goal in terms of preservation, but must be considered a tool in order to mitigate climate change, to preserve soil fertility, to preserve the ecosystem, and to enhance the ecosystem services.”

Artist Evelyn Rydz uses food to highlight unseen environmental aftermaths. In 2017, Rydz unveiled “Salty > Sour Seas“, an interactive installation at The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston that examined how water systems are changing. The installation included space where visitors could paint with water from local rivers and the ocean on pH test paper and taste the effects of ocean acidification by eating fishy popsicles made with phytoplankton and citric acid, dyed blue with algae-derived pigments, and dipped in sea salt.

Phytoplankton is “the base of the food web and is critical to the air we breathe,” Rydz says, later pointing to estimates that these algae produce at least half of the oxygen in our atmosphere. “We don’t see ocean acidification and so I wanted to bring attention to something that’s so tiny and out of sight and yet has these huge impacts on our daily lives.”

For her next piece, Rydz is rebooting a food storytelling project, this time with an eco-twist. Since 2016, she’s hosted communal potluck meals that invite women of different ages, ethnicities, and cultural backgrounds to bring a dish that gives them a sense of home and to share the story behind it. Called “Comida Casera“—Spanish for “food from home”—the project is now open to anyone and has welcomed participants from 30 countries. Rydz is updating it to focus on the past and future of home—what are we losing as environments shift and how do we preserve foods and traditions central to our identities?

“The power of the taste is about memory and emotion, and more specifically, really about personalizing something,” she says. “It literally becomes part of us.”

Disclosure: The Center for Genomic Gastronomy exhibits some of its work in the MIT Museum at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The author works for MIT in a different department and had no connection to any affiliated sources prior to reporting this story.

Christina Couch writes about brains, behaviors, and bizarre animals for kids and adults. Her bylines can be found in The New York Times, NOVA, Smithsonian, Vogue.com, Wired Magazine, and Science Friday.