Earth Day And The Evolution Of The Environmental Movement

From the first Earth Day in 1970 to today’s youth climate strikes, researchers and activists look back at the decades-long fight for a healthy planet.

Do you want to go back in time with Science Friday? Sign up for our newsletter to get more never-before digitized stories and audio bites from our archives!

Do you want to go back in time with Science Friday? Sign up for our newsletter to get more never-before digitized stories and audio bites from our archives!

Looking out from the coast in Santa Barbara, California, nearby oil rigs spike above the horizon. The county’s coastline has been home to oil wells since 1896, when it became the world’s first offshore drilling site. Over the next decades, oil production here boomed. But on January 29, 1969, thick black liquid began to bubble to the ocean’s surface. A Union Oil-operated oil rig, called Platform A, was drilling a fifth well into the seafloor oil reservoir, when enormous back pressure shot up gas and oil. The blowout spilled an estimated three million gallons of crude oil into the ocean. An attempt to cap the explosion even cracked the seabed. A 35-mile-long oil slick soon blanketed the California coast. Dead and injured marine wildlife coated in thick black oil were washed to shore.

This oil spill was just the latest example of decades of catastrophic impacts from pollution and human activity. By the 1960s, the situation was dire: “Rivers were literally catching fire, because they were so full of pollutants. Air in Pittsburgh was so heavy with soot, people drove with their headlights on during the day,” remembers SciFri host, Ira Flatow.

The year after the Santa Barbara spill, on April 22, 1970, environmental activists, supporters, and political leaders gathered to raise concern for health and the environment. This became the first Earth Day—marking a pivotal point in the birth of the U.S. modern environmental movement.

“Coming at the height of the Anti-war Movement, one year after the Kent State shootings—people were primed to protest,” says Ira, who at the time followed environmental issues and covered the rise of protests in the United States. “It was a very exciting day.”

On Science Friday’s April 21, 2000 show, Denis Hayes, one of the original coordinators of Earth Day, reflected on the atmosphere leading up to the first event.

“Something galvanized in people, and there was this transformational change in attitudes almost overnight,” Hayes said. “Americans came to believe that they had a fundamental right to a healthy environment.”

For the past 51 years, April 22 has been a day of environmental action, where the public, activists, and scientists around the world come together to amplify environmental issues and push for policy change.

Today, the objectives and participants of the environmental movement are changing—from predominantly white liberals marching in American cities to youth-led school strikes and climate change protests around the world. There’s also been growing recognition of environmental racism. In time for Earth Day 2021, Science Friday looks back at the history of the environmental movement—and how its evolution sheds light on current problems threatening the planet.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, environmental disasters were commonplace. Smog choked and killed civilians in industrialized cities. Cuyahoga River in Northeast Ohio, for example, was infamous for its oil rings, sewage, and trash—its polluted waters often set ablaze.

“We had a post World War II generation that had come to understand that unhealthy pollution of the air and the water and food was just sort of part of the way things were,” Hayes said in 2000. “We noticed that year after year, after year, it was getting worse.” He added, “Simply breathing the air in Los Angeles ultimately became worse than smoking a pack of cigarettes a day.”

The movement came with the wave of activism sweeping 1960s and 1970s America. Women’s Rights, the Anti-war movement, and the Civil Rights movement were all at their peak. People were demanding change and equality—and Earth Day organizers wanted the environment to be added to the political agenda.

The cascade of environmental hazards plaguing Americans’ health triggered “transformational change,” Hayes explained. The Santa Barbara oil spill was a tipping point for leaders like Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, who advocated for environmental values. Nelson, inspired by college students’ Anti-war and Civil Rights demonstrations, had an idea for teach-ins on college campuses about air and water pollution. But the organizers, led by Hayes, expanded the teach-ins into a national event, coordinating gatherings in streets, parks, auditoriums. More than 20 million people participated in the first Earth Day, with rallies taking place in cities coast-to-coast.

After the first Earth Day in 1970 came a string of pivotal environmental legislation. Throughout the 1970s, federal lawmakers passed the Clean Air Act, Clear Water Act, and Endangered Species Act, to name a few. On December 2, 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency was formed.

“In terms of our expectations, I think [Earth Day] really transcended them,” Denis Hayes told Science Friday in 2013.

“Americans came to believe that they had a fundamental right to a healthy environment.”

— Denis Hayes

Today, Earth Day has become a global event. More than one billion people take part in activities every year, like community cleanups, nature walks, and protests. However, since the 1970s, climate change has given new meaning and stakes to environmental activism. Instead of blazing rivers and oil spills, communities face catastrophic floods, wildfires, and intense storms. Climate scientists are now studying the impacts of a depleted ozone, melting glacial ice, and vanishing species. Meanwhile, technology and social media allow much larger, simultaneous demonstrations around the world demanding action to stop climate change.

“Large scale protest events used to be the goal,” Dana Fisher, a professor sociology at the University of Maryland, tells Science Friday in a recent phone interview. She has been studying climate activism since the 1990s. “Nowadays, these large scale protests, which don’t happen only in one location, but rather happen across the country, tend to be the beginning of activism and engagement.” She says a new generation is calling upon government leaders to act.

On September 20, 2019, marchers around the world took to the streets in the Global Climate Strike, part of the week-long event Global Week for Future. The event is just one of many protests that have taken place since the 2014 People’s Climate March, which launched a wave of large marches demanding action on climate change in the United States, Fisher explains. She was at the Global Climate Strike demonstration in D.C., surveying the crowd to better understand who was there, why they were protesting, and how they are influencing policy.

Historically, activism has been led by men, says Fisher. It wasn’t until the 1980s that there was more of a gender balance; today, more women than men lead activism organizations. “What’s interesting is the research really shows how the demographics change,” says Fisher. Movements are often led by young people, and the environmental movement is no exception. “There’s no question that a lot more young people have been participating in climate protests, as well as other activism,” Fisher says. However, she notes that today’s climate movement has been driven by even younger activists—kids.

She started to notice higher turnouts of younger students beginning in 2018, with the national school walkout against gun violence and March For Our Lives in response to the Parkland School Shooting in Florida. Now, we see an increasing number of youth leaders heading up organizations like the Sunrise Movement and Fridays for Future—18-year-old Greta Thunberg’s Friday school skipping campaign that turned into the climate strikes. In the 2019 spring climate strikes, the median age of protest organizers was 18.

“One of the things I really noticed in my research is the way that young people started doing their own thing, and then they started leading adults,” Fisher says, noting how a number of youth climate activists wrote a piece in The Guardian calling upon adults to join the Global Climate Strike in September 2019.

“There’s no question that a lot more young people have been participating in climate protests, as well as other activism.” — Dana Fisher

Now, we even see youth getting seats at the political table. Jerome Foster II, a New York youth climate activist and executive director of One Million Of Us, was recently appointed as a council member of the new White House Environmental Justice Advisory Board. But the issues of environmental racism and environmental justice have been garnering more attention, though they are big problems to tackle.

The conservation movement and environmentalism has a history of systemic racism. Several of its leaders and icons, including John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt, are lauded for their achievements in environmental preservation and protection, but many of their practices were steeped in white supremacy—often hurting and segregating Native Americans, Black people, and people of color. For decades, these communities, and issues of environmental racism, have been left out of agendas and policy. The ramifications are still felt today: People of color do not always feel safe enjoying the outdoors.

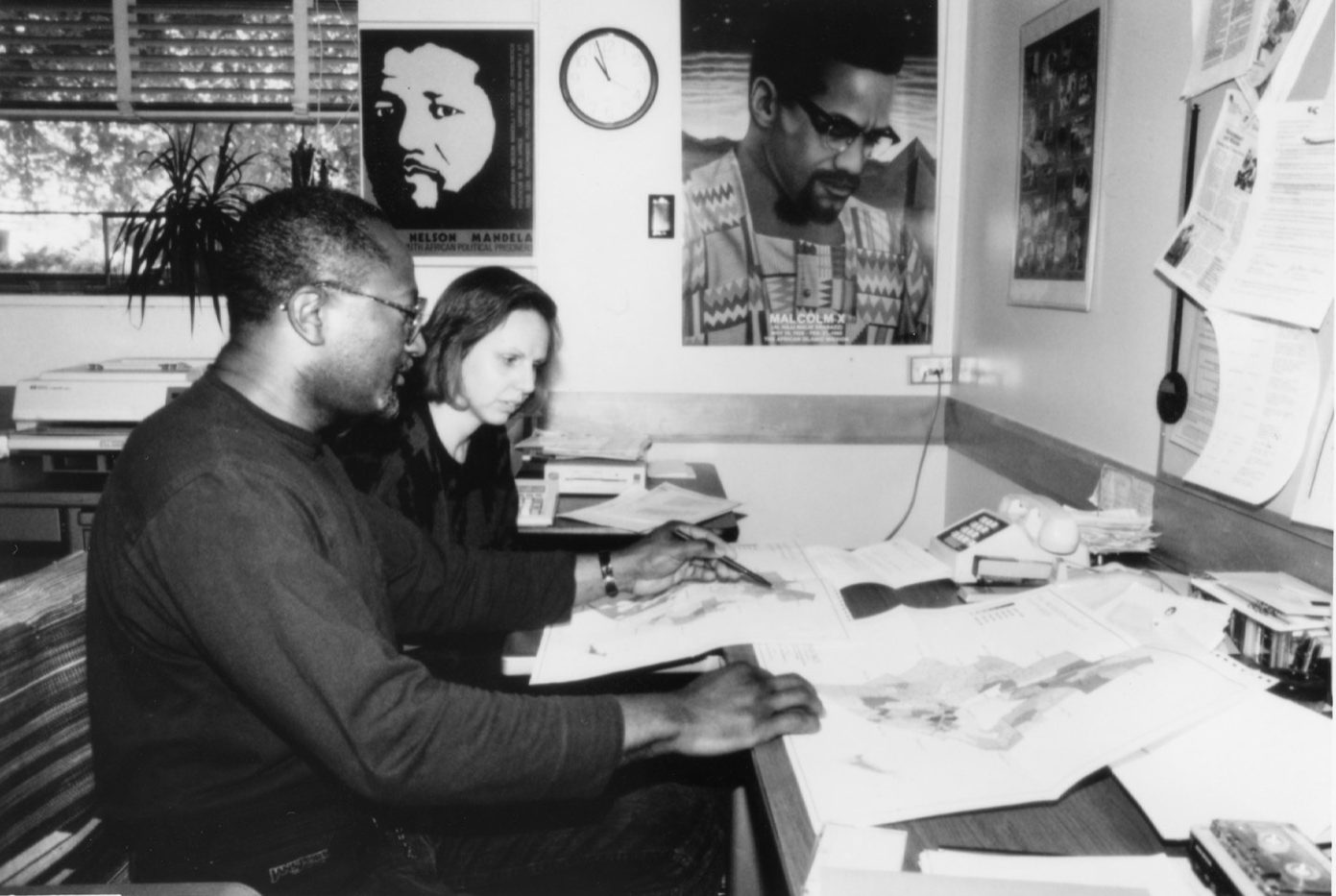

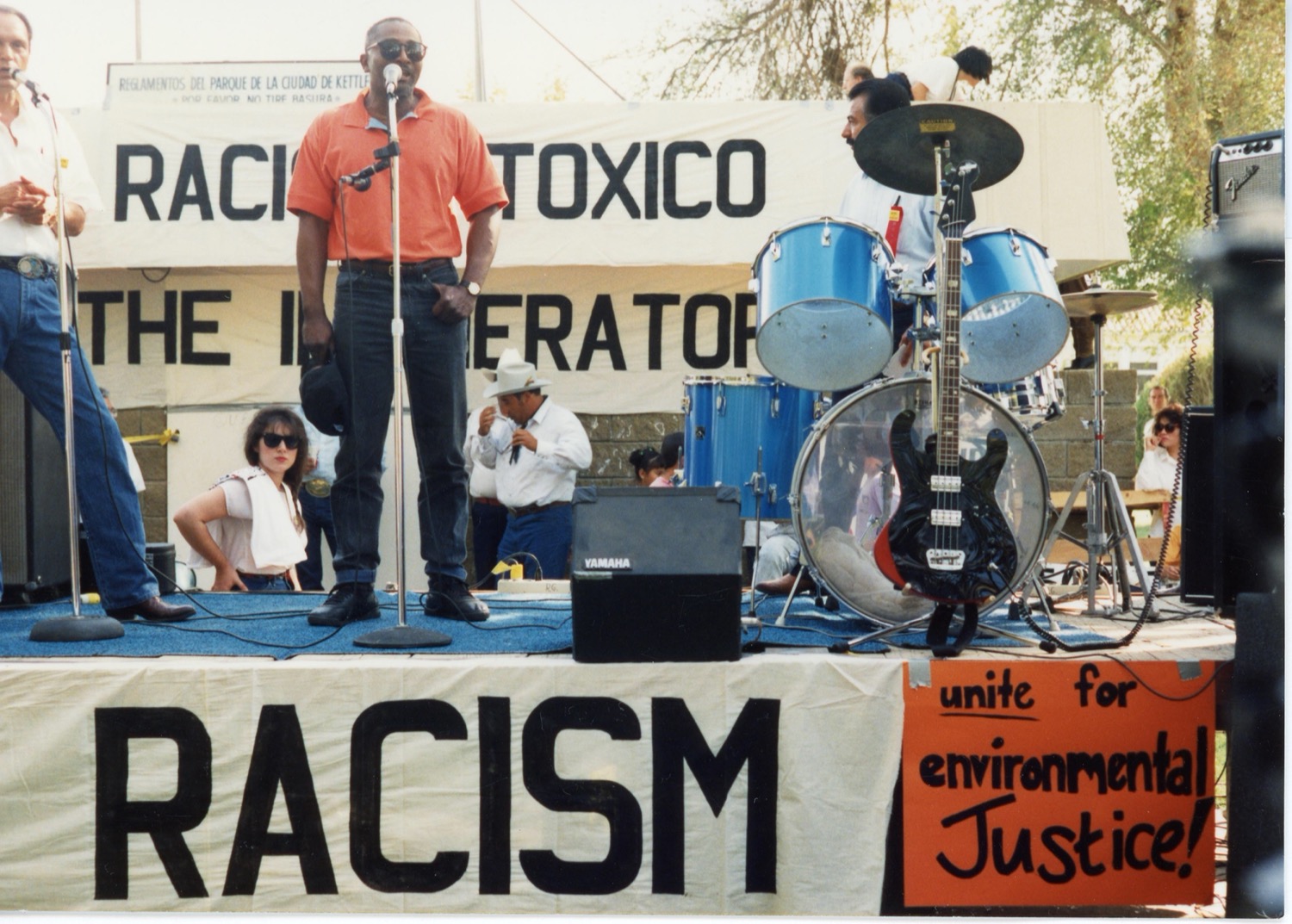

In the 1970s, the environmental justice movement had a small platform, often overlooked and not widely embraced by other movements, says Robert Bullard, distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University, and dubbed the “Father of Environmental Justice.”

“Let’s not be revisionist historians. The first Earth Day was about the environment, seen through the eyes of white middle class,” Bullard tells SciFri in a recent phone call. “White organizations had very little to do with issues around vulnerability, issues around marginalization, issues around race and justice.” At the same time, he explained that the Civil Rights movement was focused on addressing racism, voting, education, and employment. Environmental issues weren’t as much of a priority. Historians have recorded tension between the two movements—with some Civil Rights leaders stating that Earth Day was a distraction from issues of racism and expressing frustration over organizations seeming to consider Black communities and people of color as environmental problems.

Yet these issues are deeply connected, says Bullard. Not fully supported by either movement, environmental justice supporters had an uphill battle bringing awareness to the disproportionate effects of environmental public health issues on communities of color. It took decades for the environmental community and the Civil Rights community to come together.

“In 1979, environmental racism, environmental justice, was basically a footnote. But then you fast forward 40 plus years later, it’s a headline now,” Bullard reflects.

While the participants of climate marches today are still predominantly white, Fisher’s data indicates that the movement has been starting to become more racially and ethnically diverse. Simultaneously, she’s noticed changes in the motivation for people’s activism. Her surveys suggest people’s number one priority is climate change and the environment, but number two is equality. In 2017, 36% of the crowd at the People’s Climate March told Fisher they were motivated to participate by racial justice. During the pandemic, at 2020’s virtual Earth Day Live—a little over a month before George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota—51% of organizers said that they were working because of issues of racial justice.

“So there was already a shift here in the [climate] activists to start to think more about systemic racism and racial justice,” Fisher says.

“In 1979, environmental racism, environmental justice, was basically a footnote. But then you fast forward 40 plus years later, it’s a headline now.”

— Robert Bullard

The convergence of these once disparate movements is a recipe for “transformative change,” says Bullard, who is now a part of the new White House Environmental Justice Advisory Board. There are still many challenges and environmental inequities that need to be addressed, he says. But he’s excited to be working with youth leading the climate change movement and an intergenerational push for justice.

“You can see the power not just in the messaging itself, but the messengers who are out there, advocating and promoting and calling for transformative change. They’re getting younger and younger,” Bullard says. He adds that these young individuals are advocating for large-scale, institutional change needed to combat the threats of climate change. “That can only mean that we have new and emerging leaders that will not settle for little incremental baby steps.”

Archival interview excerpts have been edited for length.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.