Reflecting On The Wild With Jane Goodall, Winner Of The 2021 Templeton Prize

A look back on the groundbreaking chimpanzee research and humanitarian career of Jane Goodall.

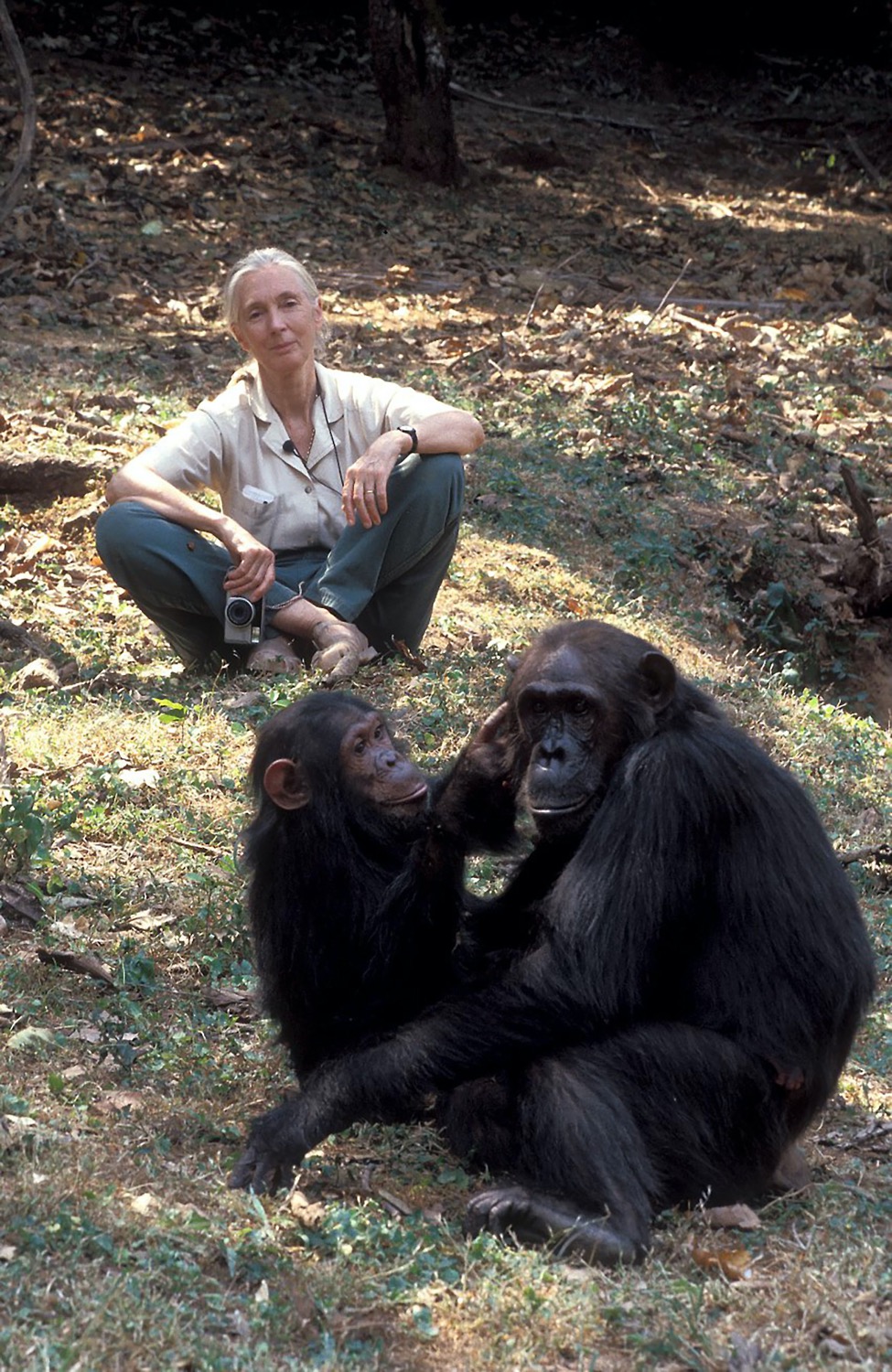

Young researcher Jane Goodall with baby chimpanzee Flint at Gombe Stream Reasearch Center in Tanzania. Credit: Jane Goodall Institute/Templeton Prize

Do you want to go back in time with Science Friday? Sign up for our newsletter to get more never-before digitized stories and audio bites from our archives!

Do you want to go back in time with Science Friday? Sign up for our newsletter to get more never-before digitized stories and audio bites from our archives!

At 26 years old, Dr. Jane Goodall ventured into a thicket of wild chimpanzee habitat tucked within the lush forest of Gombe in today’s Tanzania. It was 1960, and there were no roads or trails. Little was understood about the environment and the wildlife fortressed inside. Goodall explored this wilderness with unabashed curiosity, soaking in her surroundings and witnessing behaviors of chimpanzees that had never been seen before.

“It was absolutely unknown,” Goodall told Science Friday in 2002, when Ira sat with the primatologist and global conservationist for the first time in our New York studios.

In October 1960, just four months into her field work, Goodall watched in silent fascination as one chimp crouched over a termite mound. Naming him David Greybeard, after his silver stubble on his chin, Goodall watched him poke a piece of grass into the mound and raise it to his mouth to eat the termites—almost like he was fishing for the insects. Goodall witnessed the first account of chimpanzees making tools.

“I couldn’t actually believe it,” she said. “I had to see it about four times.”

Tool making was a skill many thought only humans were capable of—separating us from other animals. Goodall’s groundbreaking discovery in Gombe was the beginning of her life’s work, gradually shifting our perceptions about intelligence, social behavior, and emotions of animals. For the past 61 years, she’s continued her work with chimpanzees and the environment not only as a primatologist, but as a conservationist, humanitarian, and UN Messenger of Peace.

On Thursday May 20, it was announced that Goodall is the recipient of the 2021 Templeton Prize, recognizing decades of pushing the parameters of scientific research. Goodall has redefined the way scientists and the public view our relationship with non-human creatures—and what that relationship reveals about ourselves.

“I have learned more about the two sides of human nature, and I am convinced that there are more good than bad people,” Goodall said in her acceptance statement for the Templeton Prize. “There are so many tackling seemingly impossible tasks and succeeding. Only when head and heart work in harmony can we attain our true human potential.”

“We are part of the natural environment. We’re not separated from it.”

Goodall has gone on to write books, work on documentaries, and launch youth community programs, such as Roots & Shoots. She communicates her message in front of thousands at events—usually beginning with her unforgettable impersonation of a chimpanzee’s booming pant-hoot, which she demonstrated for us on air in 2002.

Goodall was drawn to wildlife at an early age. During her childhood in England, she would watch earthworms wriggle in her bed and hide for hours in a hen house honing in on how the birds laid eggs. When she was about 10 years old, she avidly read the many adventures of Tarzan of the Apes. “I read the books, fell in love with Tarzan. He’s got that wife, Jane, you know, so I was terribly jealous of her,” she told SciFri in 2002. “That was when my dream started. When I grew up, I would go to Africa, live with animals and write books about them. That’s how it all began.”

When she was 23, Goodall saved up money from low-wage secretarial and waitressing jobs to take a trip to a family farm near Nairobi, Kenya. That’s when she called up paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, then curator of the Natural History Museum in Nairobi, and landed an opportunity to follow him into the field—even without a college degree or formal scientific training. Goodall began her journey studying social behaviors of chimpanzees.

Dr. Jane Goodall with alpha male Figan at Gombe National Park in Tanzania. Credit: Jane Goodall Institute/Templeton Prize

After collaborating and seeing her natural knack for wildlife study, Leakey pushed Goodall to attend the University of Cambridge. However, many academics disregarded her experience in the field—her descriptions of chimpanzee personality, emotion, and sociality were even met with hostility, she told SciFri.

“I couldn’t talk about their personalities, these vivid personalities that I by then I was beginning to know. I certainly couldn’t talk about them being capable of rational thought, which they clearly were. And finally, worst sin of all, was that I was ascribing to them emotions, like happiness, sadness, and so forth.”

Despite push back, throughout her career Goodall continued to write about how chimpanzees kiss and hug, grieve over the death of others, and exhibit violent, dark behaviors to neighboring chimp groups—not dissimilar from human behaviors. “I thought they were so like us, but rather nicer. They may even have a series of events not unlike primitive warfare,” she said. “That was very, very shocking.”

“I try and keep the forest in me.”

In the late 1980s, Goodall left the world of research, but her work with chimpanzees and wildlife continued—shifting towards conservation and animal welfare after noticing dwindling population numbers in the wild and maltreatment of chimps in research labs. The Jane Goodall Institute supports dozens of research projects and conservation programs. On Science Friday on March 20, 2020, Goodall returned to speak with us about the need to act against the climate and pollution threats to the planet—and our footprint in the natural world.

“It’s absurd to think you can have unlimited economic development in a planet with finite natural resources,” she said. “I learned about the interconnectedness of everything out in the rainforest, where you learn that every species, no matter how small, has a role to play.”

Though her work has taken her far from the wild sanctuary of Gombe’s chimpanzee habitat, Goodall says she is still connected to the forest—no matter where life leads her.

Listen to an extended cut of the September 27, 2002 interview with Jane Goodall from the archives.

Dr. Jane Goodall in Gombe on July 14, 2010. Credit: Jane Goodall Institute/Templeton Prize

Archival interview excerpts have been edited for length.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.