He Found A Bizarre Octopus, But No One Believed Him

In 1990, diver Arcadio Rodaniche’s findings about a highly social octopus were dismissed. Decades later, his work was validated.

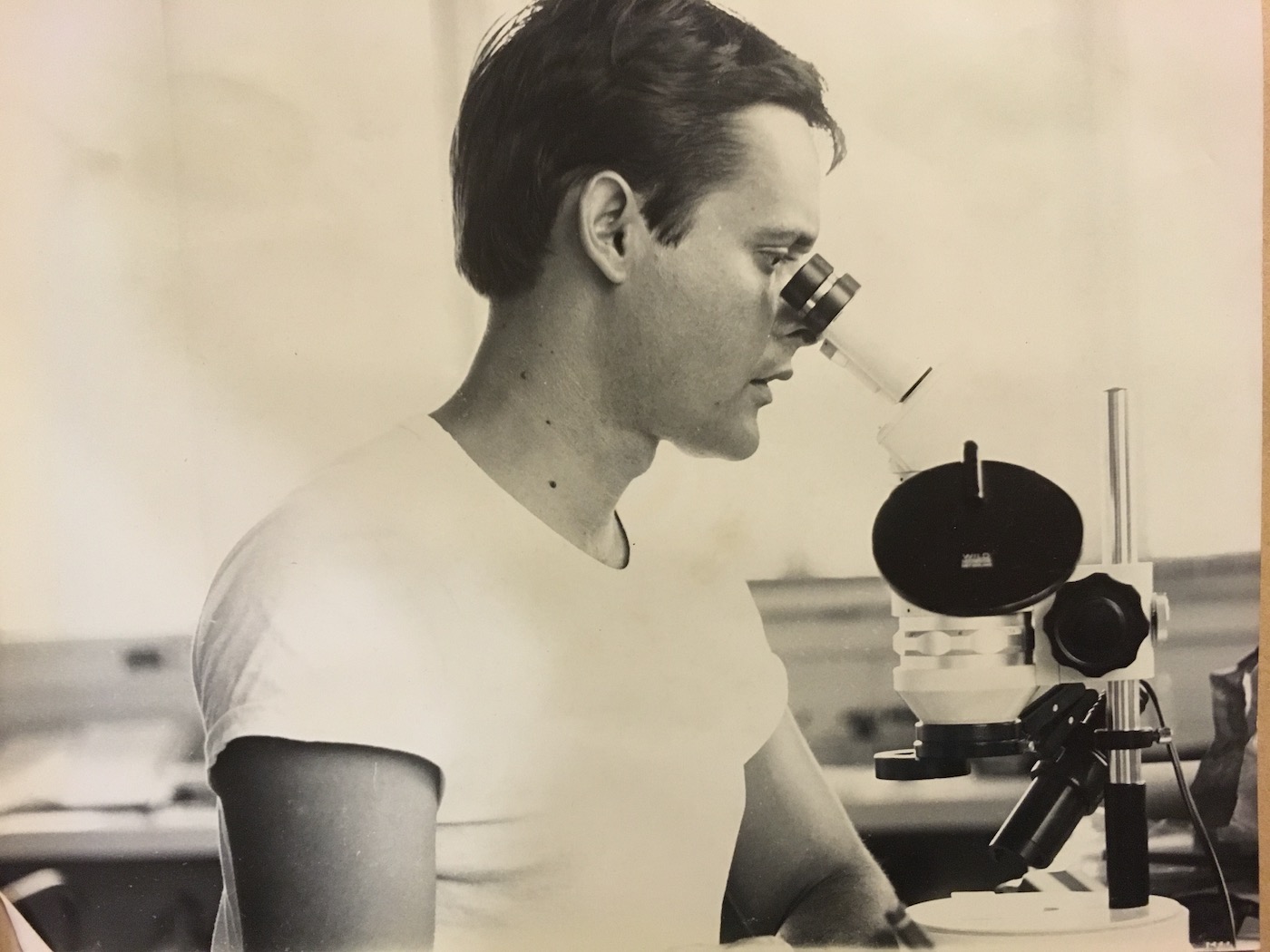

Arcadio Rodaniche during his early days at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Image courtesy of Denice Rodaniche

A few hundred yards off the Pacific coast of Panama, about 30 feet below the ocean’s surface, lived a colony of strange octopuses.

In this aquatic suburbia, males eyed each other while blowing detritus from the front of one den to another using their jets. Inside the dens, mothers constantly cleaned and pruned the chandeliers of eggs hanging from walls like translucent Christmas lights. Amidst tidying up, the females mated with their male partners in a passionate “kiss,” their beaks touching. Because the mothers constantly layed eggs, embryos cycled through development, hatching and swimming out of the den into the azure beyond.

These behaviors are highly unusual for octopuses, which typically socialize only to mate and then die after producing one clutch of eggs. We know about this unique creature, known as the larger Pacific striped octopus, or LPSO, thanks partly to a diver and artist named Arcadio Rodaniche.

“Arcadio has been described as a gentleman scientist,” says Dr. Gül Dölen, professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. “He didn’t have a PhD or go the academic route, but he did make a very important contribution to science.”

Rodaniche spent his adolescence using early diving equipment to explore the waters of Panama. “His nickname was ‘Salao,’ which means salty, because he was always in the water,” says Denice Rodaniche, Arcadio’s wife.

Though he had an electrical engineering degree from UC Berkeley, Rodaniche used his scuba diving skills to become a diving officer at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) at the Naos Island Laboratories, right outside Panama City, Panama.

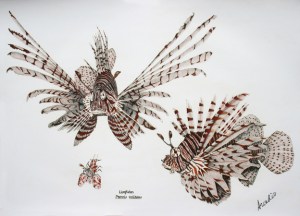

Rodaniche’s talent caught the eye of famed cephalopod researcher Dr. Martin Moynihan, the STRI’s founding director from 1963 to 1973. The late Moynihan mentored Rodaniche in studying the behaviors of the Caribbean reef squid (Sepioteuthis sepioidia) through the 1970s, and they published their notes about the squid’s communication patterns in a book about the species in 1982. In the text, they also mention the mysterious octopus colony, giving it the common name of larger Pacific striped octopus while highlighting its lack of a scientific name. A self-taught artist, Rodaniche accompanied the book chapter with some of his own drawings.

Intrigued by the bizarre behaviors of this octopus, Rodaniche wanted to investigate it further and determine if it could be officially classified as its own species. Embarking on his own research project, he obtained a few live LPSOs caught in local fishermen’s nets, and kept them in the Naos laboratory where he began to study their behavior.

“He certainly knew about squid, but he also knew enough about octopus to say this is not normal,” Denice says, in reference to the LPSO’s unusually social behavior and ongoing reproductive cycles. “He’d get attached to them. But sometimes, they would escape … and he’d find their bodies outside as they tried to get back to the bay. He would say, ‘Antoinette died the other night.’”

While Rodaniche worked to keep these strange cephalopods alive with little knowledge about octopus care, he was visited by Dr. Roy Caldwell, a biologist who was on sabbatical and wanted to see the odd happenings within Rodaniche’s laboratory.

Although Rodaniche was in touch with other cephalopod researchers, Panama’s limited resources, combined with the bizarre behaviors of the LPSO, made it difficult for him to fully understand his observations. Panama had little in the way of the internet in the 1980s and ’90s. “While the University of Panama was free and the libraries were free, you had to pay to copy pages of books, so often people just tore out the pages they wanted,” Denice says. “You’d try to find a book, and 10 pages would be missing.”

Rodaniche compiled his research, extensive observations, and some underwater images, and presented his findings at the 1990 Gilbert L. Voss International Symposium at Woods Hole, Massachusetts. He introduced the LPSO to the wider cephalopod research community for the first time but returned from the conference disgruntled, Denice says. No one had seen this mysterious octopus, and they didn’t seem to believe his claims about it.

Undeterred, Rodaniche tried to publish his findings in the Bulletin of Marine Science. However, just before Christmas 1990, his paper was rejected with extremely critical and often personal comments, Denice says. Disgusted by the lack of support, Rodaniche gave up trying to publish his work.

For decades, the only record of LPSOs was a brief paragraph-long note and one image—a drawing by Rodaniche. It remained the only image of the octopus until 2015.

“This note was a delicious glimpse of the possibility of this weird octopus that lived in groups and didn’t die after it laid eggs,” says Rich Ross, a senior biologist at the California Academy of Sciences and an independent researcher. “I call it the ‘Bigfoot’ of octopuses because based on what we thought we knew about octopuses, it shouldn’t exist.”

Rodaniche’s art became his focus after he retired from research. The haunting image of the LPSO was one of many illustrations of marine life he observed around Panama, the Great Barrier Reef, and beyond, from great barracuda to scuttling blue crabs.

However, his research was not in vain. In 2012, Caldwell was able to obtain several LPSO specimens from a live animal wholesaler, and reached out to Rodaniche, asking him to co-author a study about them. The paper, published in PLOS One in 2015, validated every single one of Rodniche’s observations, from overly social behaviors to beak-to-beak mating.

“His gut and intuition were correct; he did find something very cool and unusual,” says Dr. Christine Huffard, a researcher at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute and a co-author of the PLOS One study. “And it’s a real shame to the scientific community that it was buried for 30 years.”

The news exploded with the publication of the paper about this weird octopus, although Rodaniche’s contributions were rarely mentioned. Rodaniche died of cancer just five months after the paper was published, leaving a significant but little-known legacy.

“The absence of a PhD by Arcadio Rodaniche does not detract from the significance of his contributions to studying octopuses and other cephalopods,” says marine biologist Dr. Alex Schnell. Rodaniche’s work should encourage both professional and amateur researchers, Schnell says, “highlighting the collective effort in advancing our understanding of subjects such as octopus research.”

Dölen hopes to carry on Rodaniche’s legacy by determining if the larger Pacific striped octopus is distinct enough to be its own species and, if so, to name it after Rodaniche.

“I think that that is appropriate, given how, you know, long he waited to be validated or vindicated,” Dölen says. “I think it is going to be a really important species. And I would like to honor him in that way.”

Correction: This article originally misstated the depth and location of the the LPSO colony in the opening paragraph. It has been updated.

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is a freelance science writer and a science communicator at JILA, a physics research institute in Boulder, Colorado.