A Yearbook Of Seeds

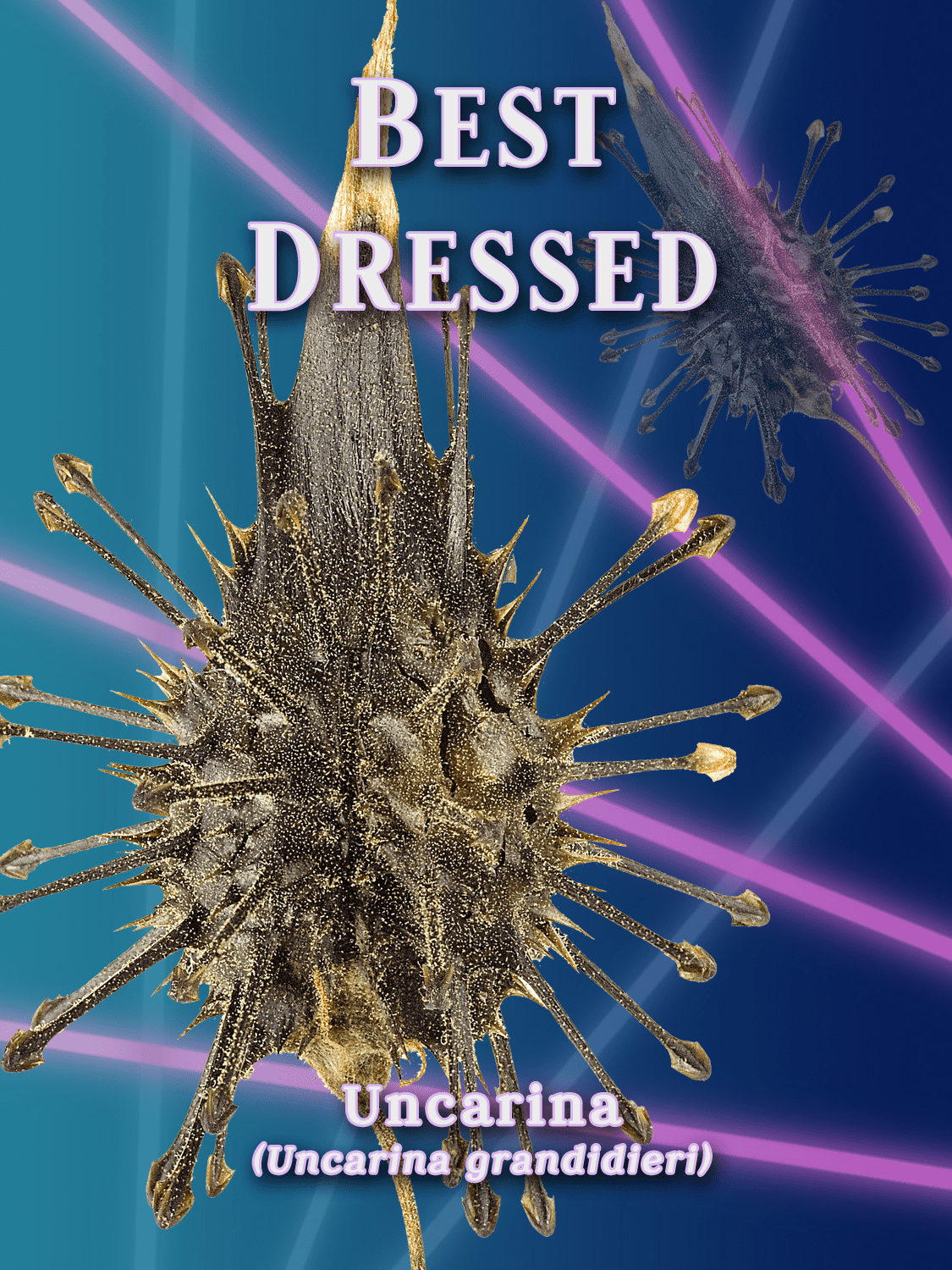

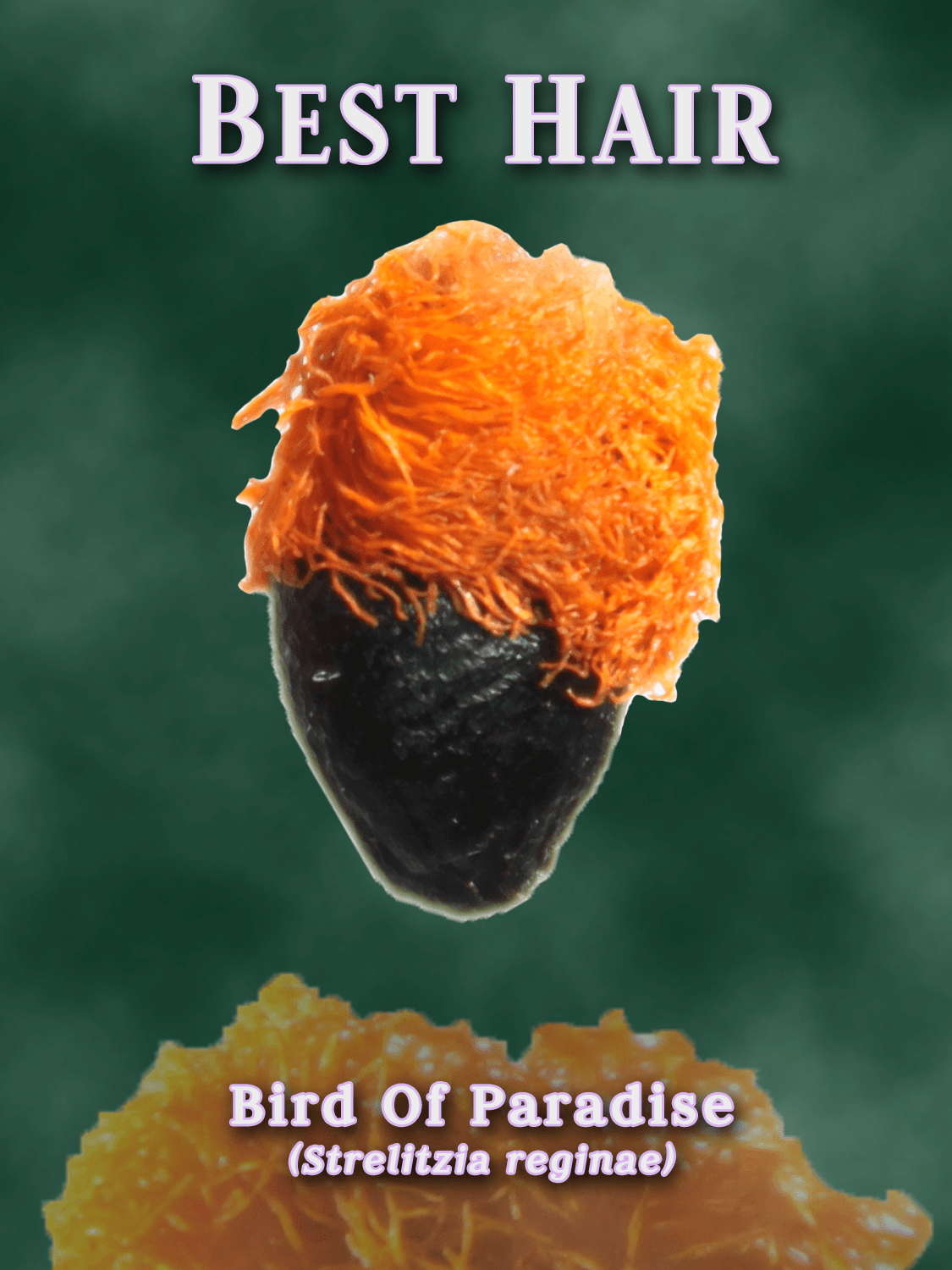

From the Uncarina seed’s fashionable coat to the flowing orange locks of the Bird of Paradise seed, we present this year’s seed superlatives.

Credit: Roger Culos/Wikimedia/CC-BY-SA. Image courtesy University of Chicago Press

If there were a yearbook of seeds, the spiky and sticky seed of the Uncarina tree, a succulent shrub in the savannahs of Madagascar, might win “best dressed.” The end of each spike on the seed coat is embellished with a strong hook that helps the fruit (and the seed inside) hitch a ride on animal fur and feet. But sometimes, those clingy spines might do their job too well.

“I once saw one with a dead snake around it,” says Paul Smith, a botanist and seed specialist at Botanic Gardens Conservation International in the United Kingdom, who came across the specimen. “You can see how it was caught by the fruit with just the skeleton wrapped around it. That’s how sticky these seeds are.”

The Uncarina tree is one of the more than 370,000 estimated seed-bearing plant species around the world. As a conservation botanist, Smith travels the world studying plants and their seeds, or bundles of DNA and food for a developing plant. He’s come across seeds that evolved to have all kinds of shapes and sizes (from the up to 37-pound Coco de Mer to the tiny, dust-sized orchid seed), colors and adaptations (from the electric blue traveler’s palm to the explosive Himalayan balsam). Many of these traits have allowed some to survive in the harshest environments, like Antarctica or the Sahara; others can remain viable for centuries.

“All plant diversity is important,” Smith tells SciFri on the phone while out on a field study in the Mafinga mountains in the remote northeast of Zambia, helping local leaders establish nurseries of indigenous plants. “Seeds give us an opportunity to save plants that would otherwise become extinct for future generations.”

There’s around 2,000 new seed species found each year, Smith writes in his new book, Book of Seeds: A Lifesize Guide to Six Hundred Species from Around the World, but many species are disappearing. Between 60,000 and 100,000 plant species are threatened with extinction—about one-fifth of the total number of known plant species, Smith writes. The primary culprit is human clearing, but climate change is expected to make a bad situation worse, he adds. Many rare plant species at risk in these transformed landscapes could be pressured even more from the loss of key animals and insects, Smith explains. “Their pollinators or dispersers may be extinct or no longer in the vicinity,” he tells SciFri.

Despite the environmental challenges, these resilient capsules of life can be the root of their solution, Smith says. Studying seeds can assist with creating new crop varieties to better food security and biofuels or renewables for energy, among a list of uses, he says. Seeds are also being used in medical research, such as the Madagascar rosy periwinkle seed, which contains cancer-beating compounds, and snowdrop seeds, which include a chemical compound used as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

“People who know about plants are desperately needed if we humans are going to survive on this planet in the future,” Smith says.

While “the most beautiful seed is in the eye of the beholder,” says Smith, we couldn’t help but imagine how some seeds would fare in a hypothetical yearbook—from the Uncarina’s “best dressed” seed coat to the Bird of Paradise’s flowing “best hair.”

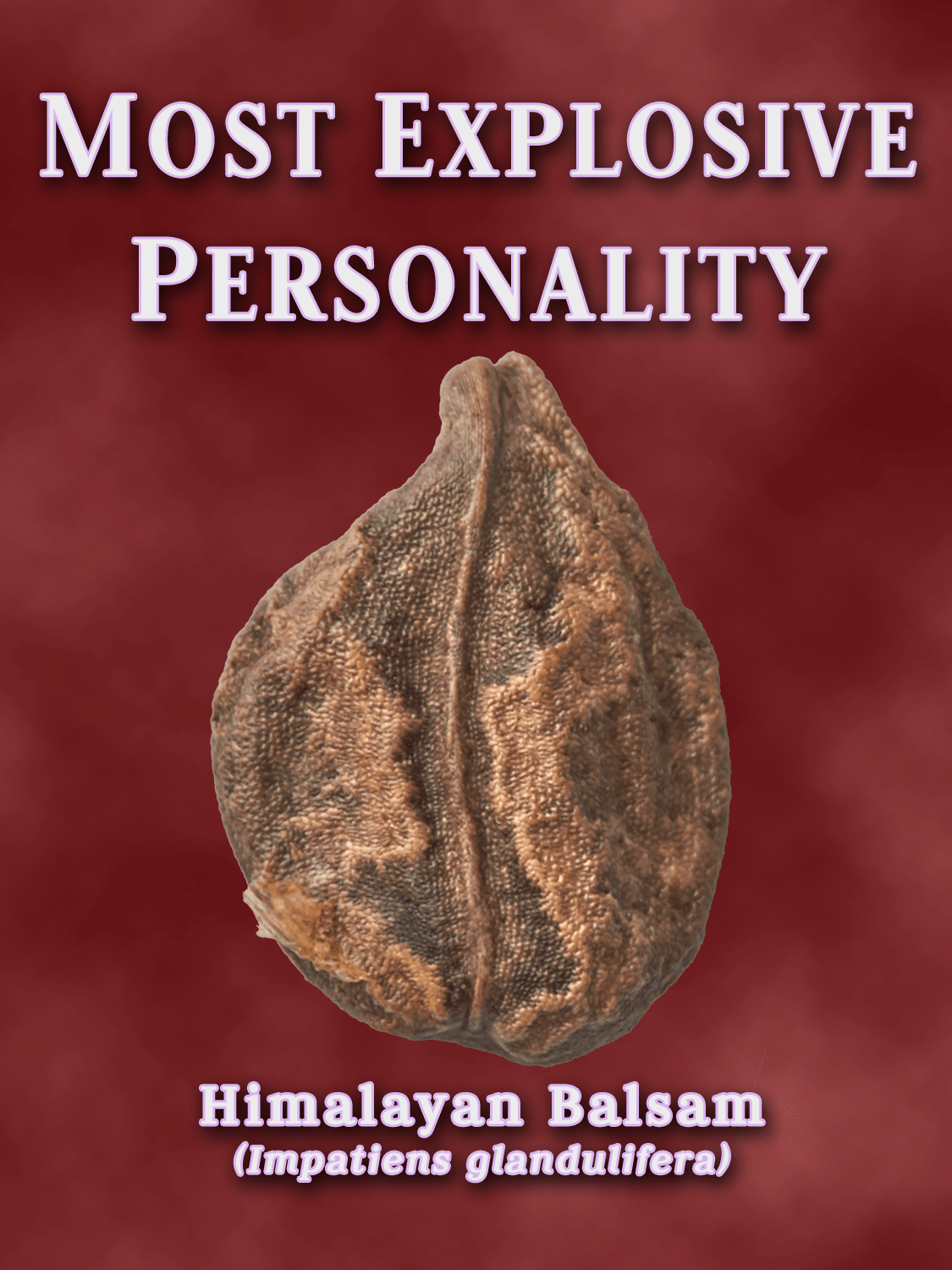

Distribution: Native to the Himalayas, and widely cultivated and naturalized in Europe, North America, and New Zealand

Nestled inside a special pod, the seeds of the Himalayan Balsam might seem unsuspecting and docile—but they can be a bit touchy. Just the slightest brush of your hand can cause the seeds to burst and disperse across a wide area. In fact, in some cases the seeds can fly 23 feet away from the plant.

“The moment that you touch the fruit [containing the seed] it gives you a real shock,” Smith says. “It’s like something is alive on your fingers. It shoots the seed out.”

Explosive pods is a useful dispersal method that allows seeds to reach farther distances and increase their distribution (which can lead to species becoming invasives). While there are many different plants that fling seeds—in fact, the genus name Impatiens is linked to the seed’s explosive mechanism—the Himalayan Balsam’s seed pod is notably, “really weird,” says Smith.

“It is slimy and feels like you have caught a particularly active worm,” he says. “This is because the fruit is tightly twisted and wound up, ready to release the seeds. Quite a creepy feeling.”

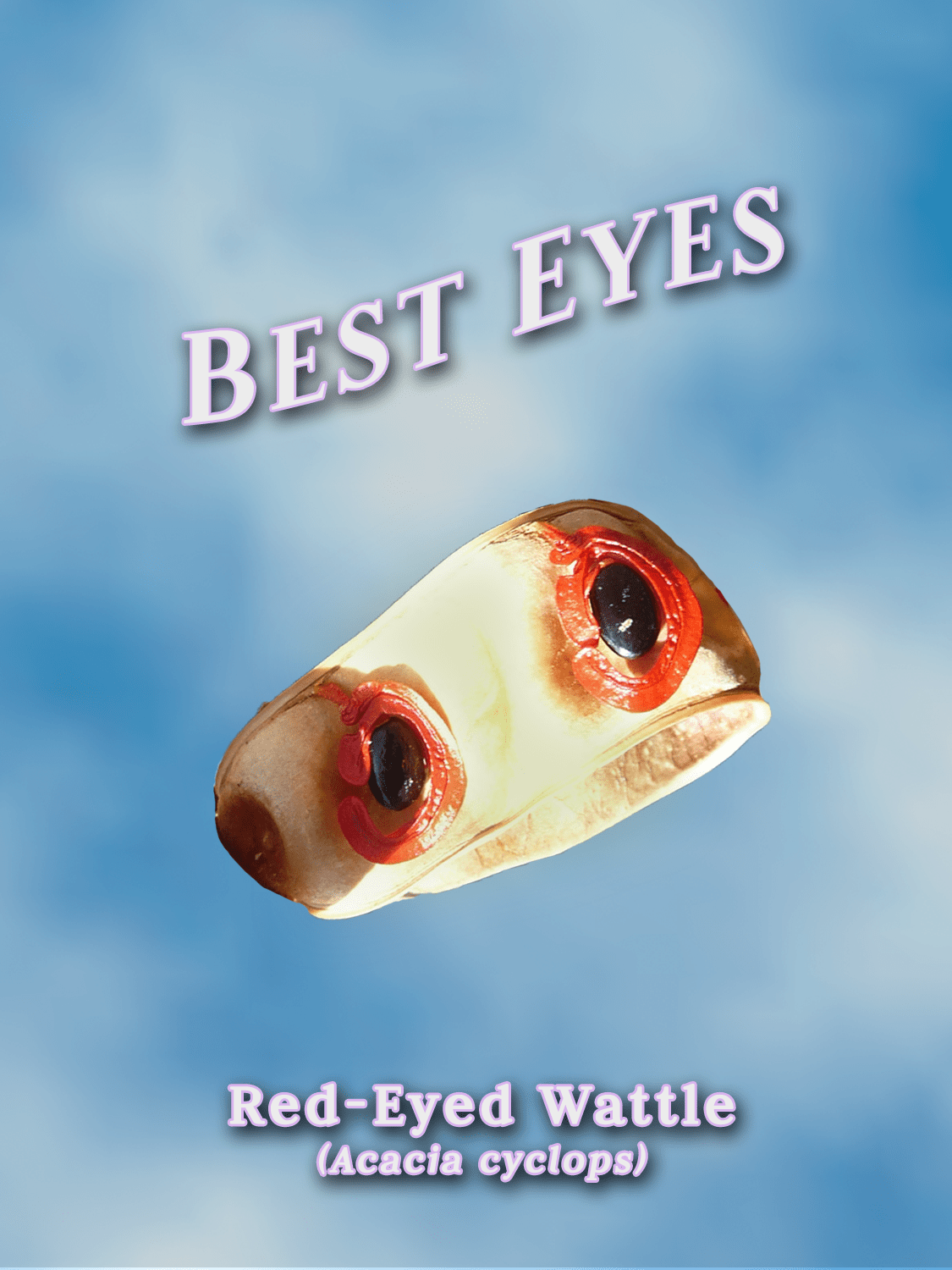

Distribution: Native to Australia, naturalized in Africa

The species name Acacia cyclops is rather appropriate for this dense shrub—like the one-eyed mythical giant, this plant’s seed seems to be staring right back at you. It might remind you how your eyes look when you haven’t gotten enough sleep. The red-eyed wattle, as it’s commonly known, has an orange-red fleshy “iris” that circles the dark brown seed.

The colorful “eye” is an adaptation that attracts all kinds of birds, such as wattlebirds, singing honeyeaters, and silvereyes, that are the species’ dispersers. But the adaptation may work a little too well: “One of the problems is that it was introduced to South Africa as a useful tree and it’s now been dispersed widely by birds and people are having a real problem getting rid of it,” says Smith.

Distribution: Native to South Africa, widely cultivated around the world

Just as alluring as the flower in bloom, the seed of the Bird of Paradise has a lovely set of flowing orange locks, or arils. While there are other seeds with nice “hair”—from the common reed’s silky fringe to the electric blue mane of the traveler’s palm—the Bird of Paradise seed’s bright shock of orange hair has an uncanny resemblance to what we see on humans.

“It does look a lot like hair on top of the head,” says Smith. “Some people have said it looks like Donald Trump or an Irish lad.”

The hairlike structures help with dispersal, the color not only catching our eyes, but those of birds and other seed dispersers.

Distribution: India, Southeast Asia, Queensland, Australia

The seed within this fruit of the pong pong tree—also referred to as the “Suicide Tree”—will stop your heart. Quite literally.

This common tree, often grown in hedges and gardens in India and Southeast Asia, has seeds that contain cerberin, a poison that disrupts the heartbeat by blocking calcium ion channels in the heart, often leading to death.

“It only takes the kernel of one seed to kill a person,” Smith says.

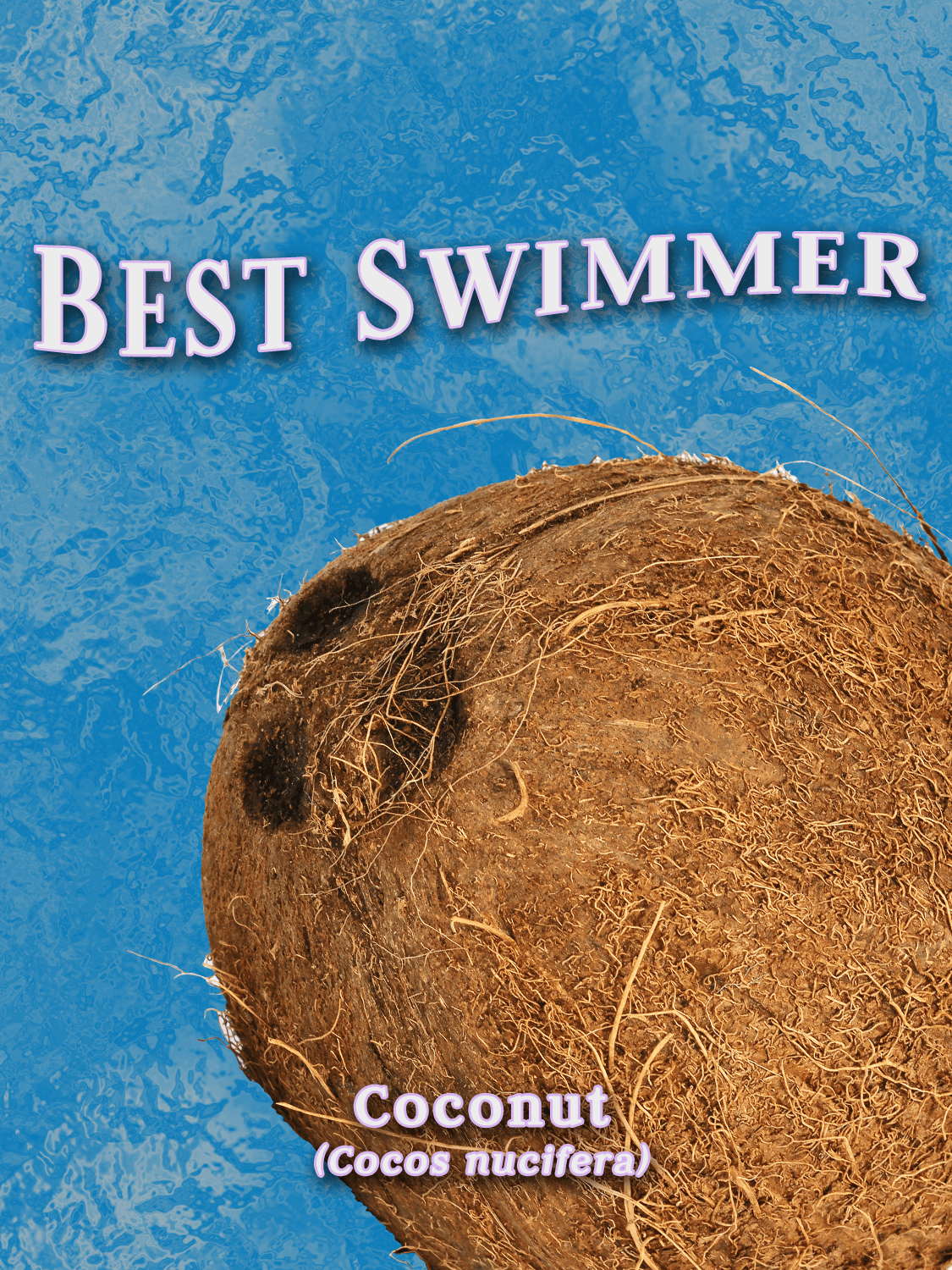

Distribution: Cultivated in tropical regions worldwide

If you’re vacationing on a tropical island anywhere in the world, you might find this sea-lover catching a wave. The woody shell, or endocarp, of the coconut helps it easily bob in the water, making the seed an excellent swimmer and traveler. And, as a successful traveler, it’s “therefore a very successful plant,” Smith says.

“There are other ocean travelers, but none of them are as successful as the coconut,” he says. By crossing oceans, coconut trees have become more widely distributed in tropical coastal systems and can be found worldwide.

Distribution: Indonesia

This seed knows how to spice up any dinner dish or dessert. Nutmeg naturally hails from the Banda Islands in the Maluku archipelago of Indonesia—a group of islands also known as the Spice Islands. When it’s ripe, the nutmeg nut splits open to reveal an egg-shaped seed, which is wrapped with a veinlike lacy covering. The seed is used as a source of spice nutmeg and spice mace.

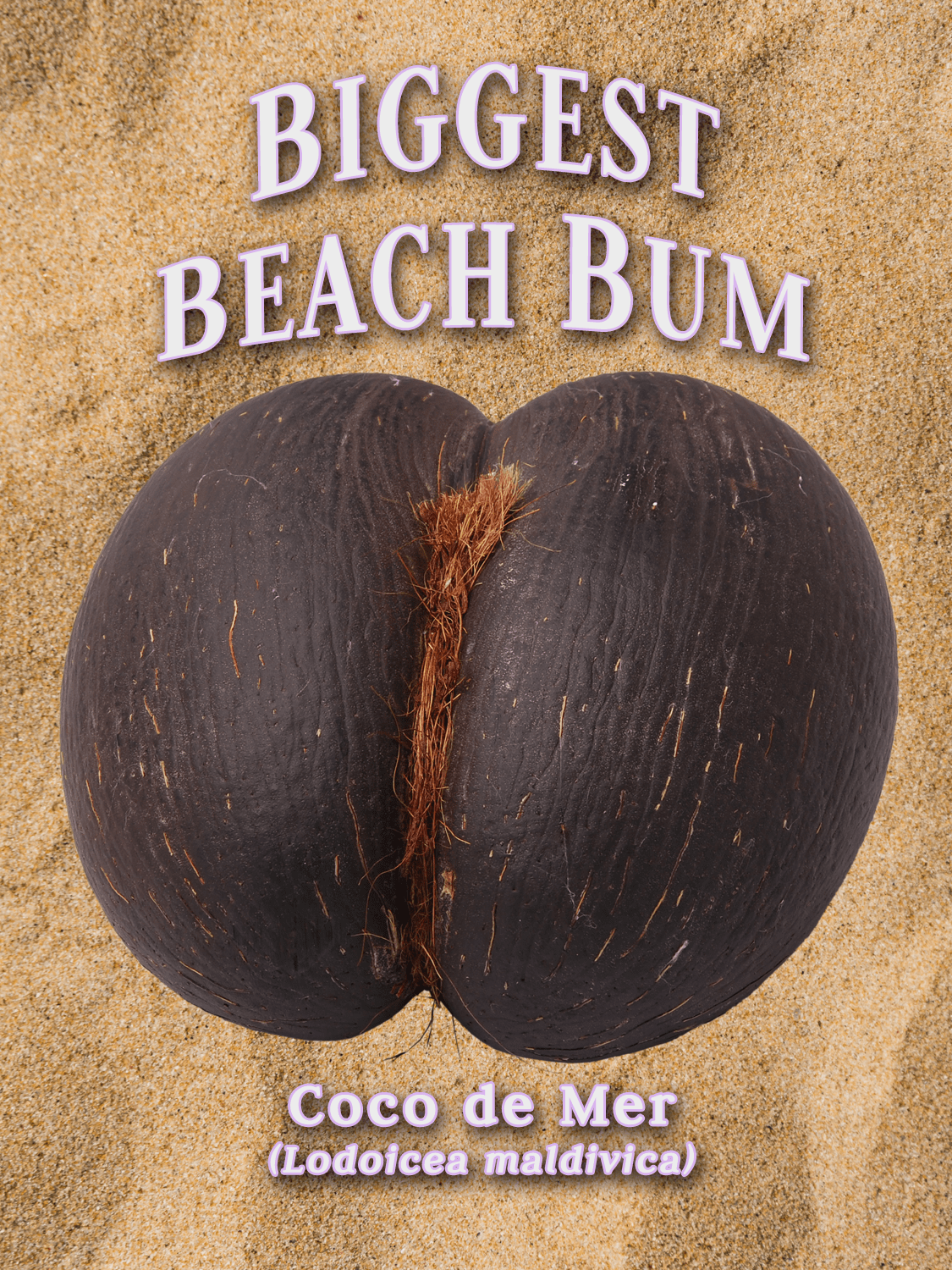

Distribution: Seychelles and Mascarenes moist forests

The seed of the Coco de Mer (literally the “sea coconut”) goes by many local nicknames: the love nut, double coconut, coco-fesse, or coconut-bottom, and, fittingly, the bum nut.

“It looks kind of like a buttocks,” Smith says. “It’s very, very valuable to people. Those seeds can sell for something like $300 each.”

Besides its unique appearance, this giant double coconut is the heaviest known seed in the world—weighing up to 37 pounds, the enormous food storage allows the developing plant to survive off seed reserves for months, explains Smith. But there’s an evolutionary trade off: Unlike the single coconut, the island-bound seed doesn’t float well in water due to its size and weight. And despite what its name suggests, the Coco de Mer or sea coconut is poisoned by the salty ocean, says Smith, making it a poor traveler.

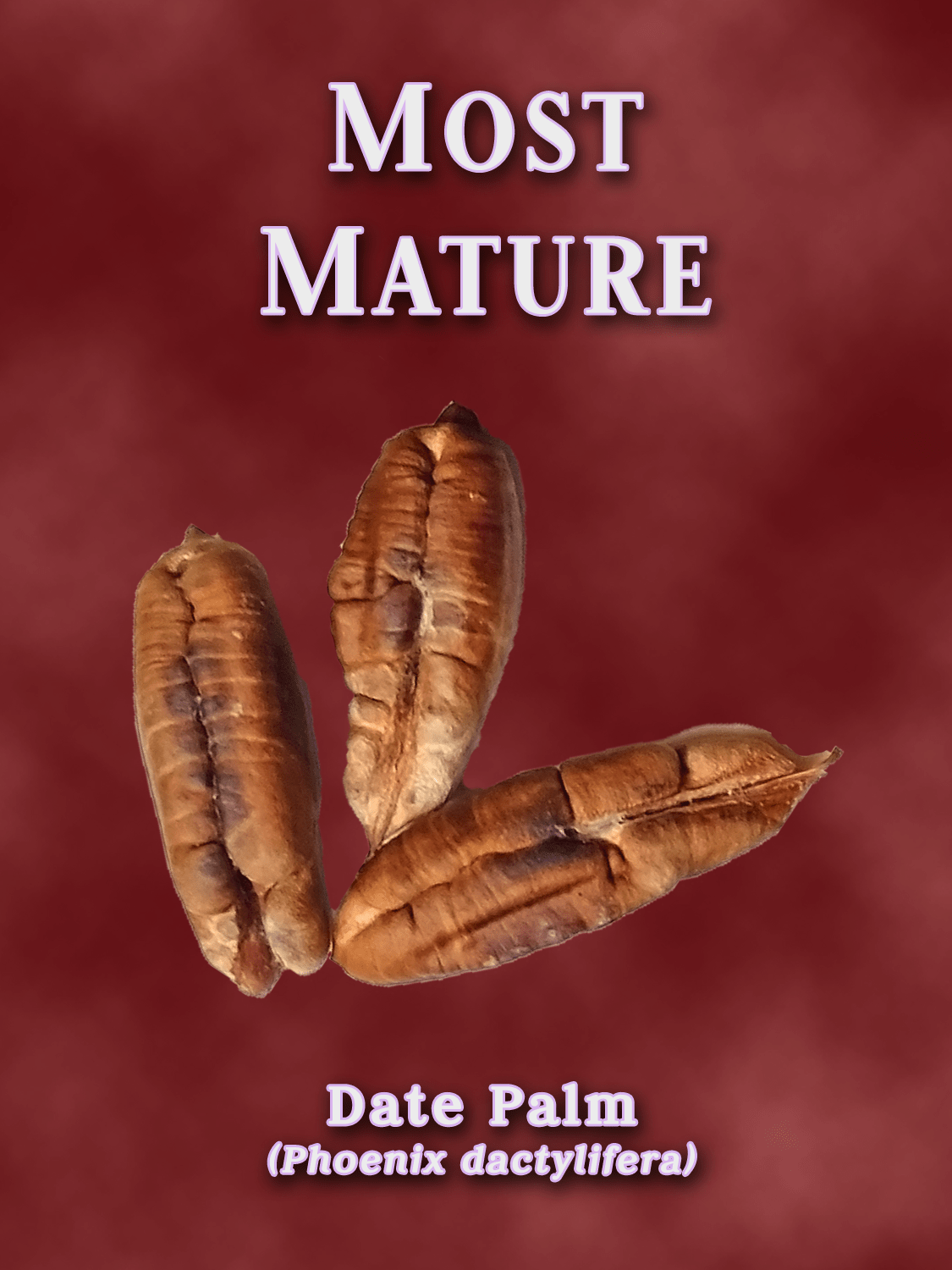

Distribution: Native to North Africa and the Middle East, widely cultivated

In the mid-1960s, archaeologists excavating the remains of Herod the Great’s palace, a crumbling fortress resting on a sheer cliffside by the Dead Sea dating back thousands of years, discovered a cache of date palm seeds in an ancient jar. Researchers carbon dated the seeds to 155 BC to 64 AD. What was surprising, though, was how well the jar’s protection and the arid climate preserved them.

In 2005, botanists treated some of the seeds with hormone-laced fertilizer and planted them. Within two years, a spritely palm sprouted making them the oldest known seeds to ever be cultivated.

The date palm is not the only species that can remain viable for such a long time. Smith points to seeds in the pea family, “but they go on for centuries rather than millennia…I think the date palm wins without a doubt.”

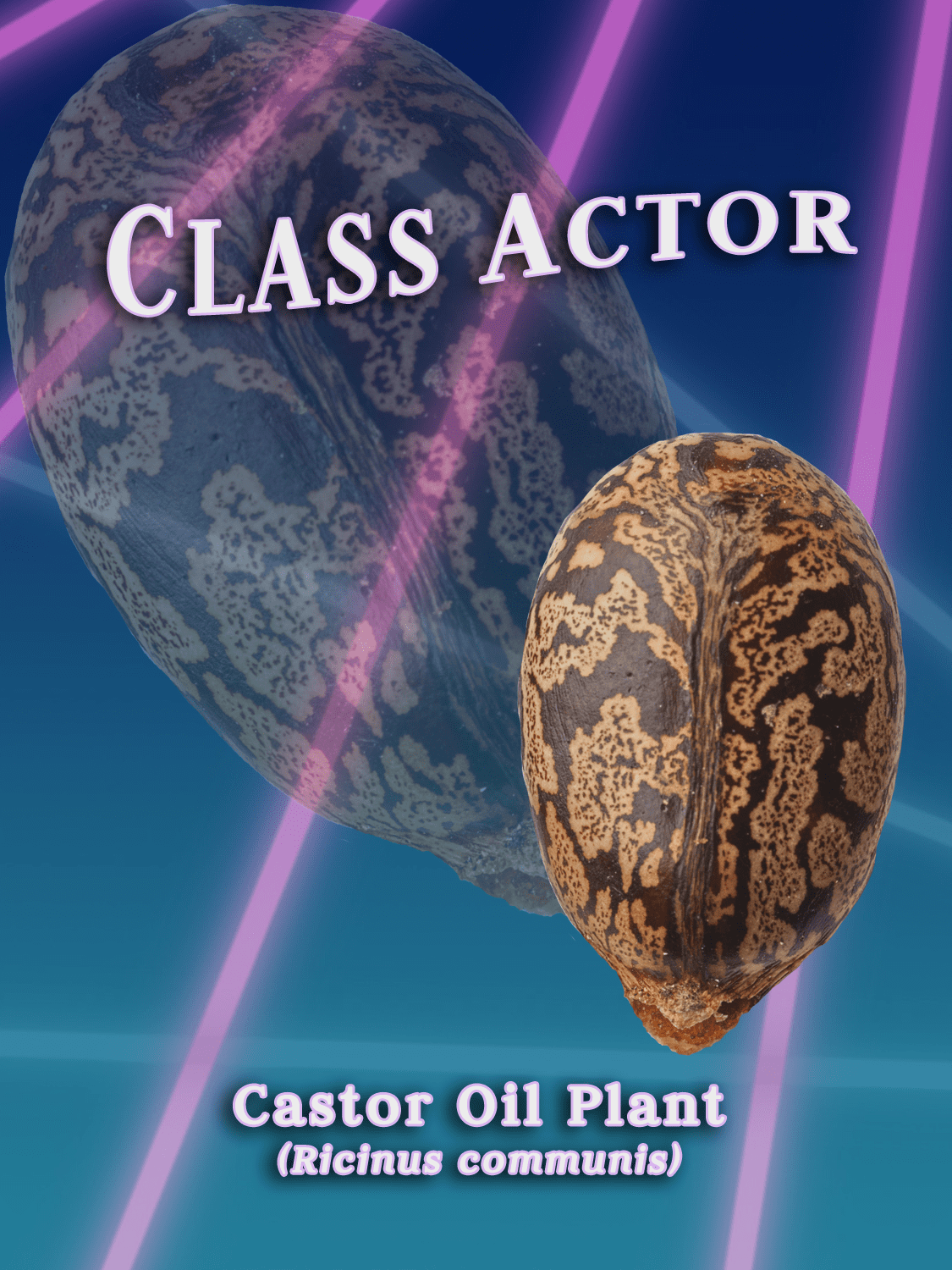

Distribution: Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia

The blotched, mottled brown exterior of this castor oil seed helps it easily blend into the environment and hide from small mammals. Since ancient times, people have harnessed the shiny, smooth seeds for castor oil to use in medicine and industry. But, like many actors, if not treated correctly, they can be a deadly cocktail.

“It’s one of the most poisonous seeds in the world,” Smith says. Castor oil seeds contain ricin, and a dose the size of a few grains of table salt is enough to kill an adult human. The toxin must be destroyed through a heating process while extracting the oil from the seeds. Despite the dangers, humans continue to cast castor oil in many roles—from starring as adhesives, lubricants, soaps, and laxatives.

*Correction 7/15/2019: This article has been updated with the correct spelling of the species name Strelitzia reginae, common name bird of paradise. We regret the error.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.