A Chair Fit for Dancing

A “smart” power wheelchair enables dancers to move in new directions.

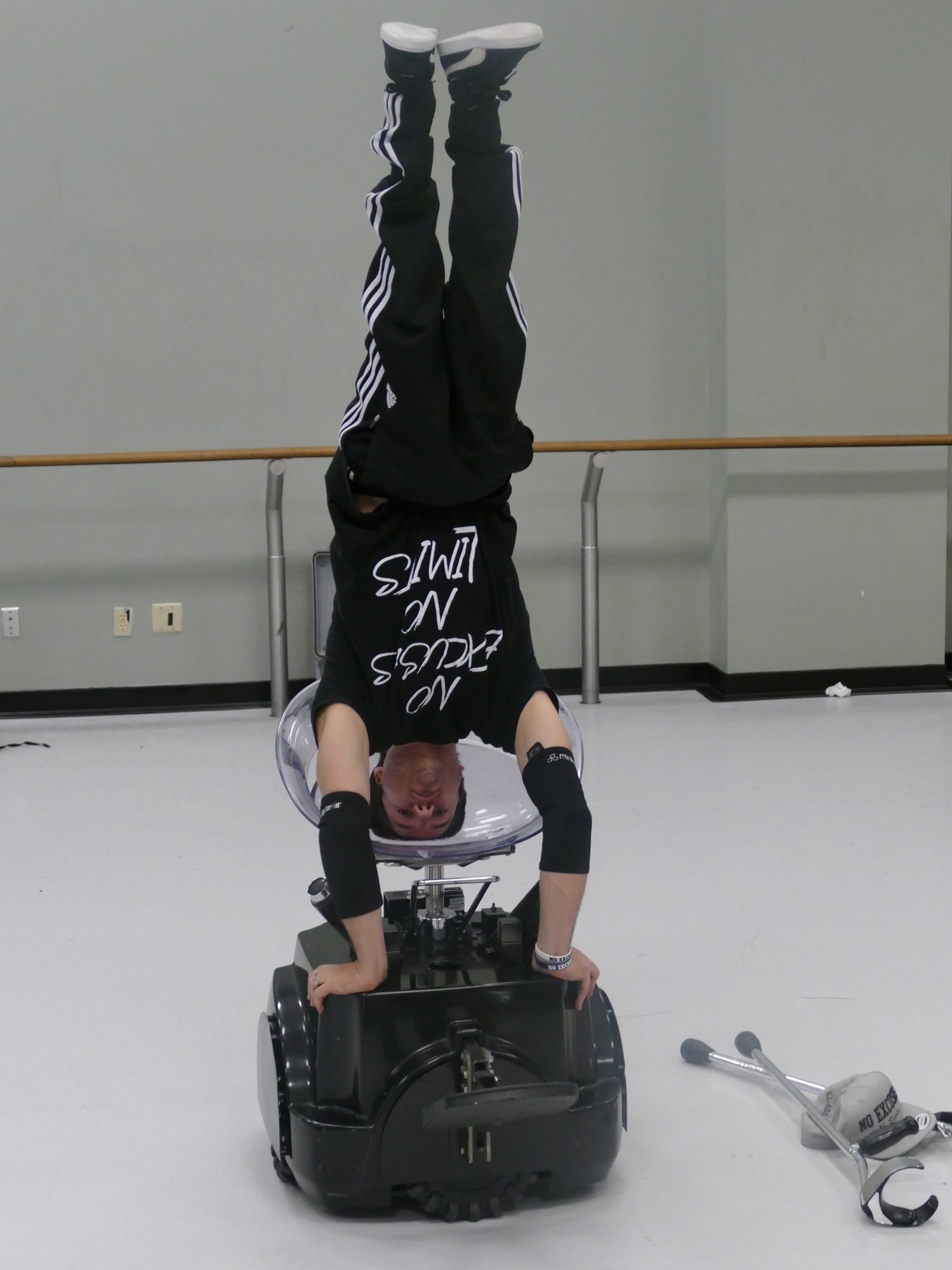

Choreographer Merry Lynn Morris (left) and dancer Frank Hull demonstrate her Rolling Dance Chair at the University of South Florida in Tampa. Photo by Tom Kramer

Frank Hull is a dancer. His body is prone to spasms, so he uses a power wheelchair to perform as well as to go about his daily routine. By manipulating the joystick, he can move forwards and backwards and pivot on an axis. The chair is sturdy—heavy-duty enough to plow through snow—and it rolls pretty fast when he lays on the controls.

Developing a dance technique using his utilitarian device has been Hull’s passion for more than 15 years. As he puts it, his craft involves developing “ways of relating to the chair with my body artistically—in essence, creating a movement vocabulary that can be turned into dance.”

So a few years ago, when Hull heard that a Florida-based choreographer named Merry Lynn Morris had invented a power chair with dancers in mind, he had to see it for himself.

“I never thought there would be a chair designed for dance,” says Hull, who’s based in Toronto, Canada. “’Course, I had to get to Florida. Didn’t matter how.”

When he finally met Morris at the University of South Florida (USF) in Tampa in May 2013, Hull found a chair tailored for artistic expression. The device was sleek and compact, its wheels hidden from sight. And it could move in all directions—including from side to side and diagonally, which commercial manual wheelchairs and most power chairs, including Hull’s, can’t do.

But the chair had another attractive feature: It was “smart.” To command the device, a user straps on a portable, wireless control—in this case, a cell phone—to a mobile part of her body, say the head or the upper back. When she leans in a desired direction, the phone detects the movement and instructs the chair to follow suit. (As far as Morris knows, there are no wireless power wheelchairs on the market; she has a U.S. patent on her chair’s technology.)

“[The chair is] absolutely unique; I’ve never seen anything like this at all,” says Mary Ellen Buning, a seating and mobility specialist for the University of Louisville Physicians in Kentucky. Someone with good control of the muscles in her torso, she says, “could really make full use of this chair for expressive dance.” (Buning hasn’t seen the device in person but watched a video of it in action.)

When Hull gave the chair a spin, he was struck by the freedom of movement it afforded him. “I wasn’t tied to my joystick,” he says. “I could feel the dance more.”

Morris calls her invention the Rolling Dance Chair, and she’s been working on it for more than a decade, earning five patents in the process. To her, the chair is more than an accessibility device—it’s an opportunity to explore new dance techniques.

“The exciting part for me is actually when different people get in it with their different bodies and their different dance backgrounds,” says Morris, who’s the assistant director of the dance program at USF’s School of Theatre and Dance. “There’s a lot of different ways the chair could be used as a movement tool.”

Morris can hardly remember a time when she wasn’t leaping and twirling. She grew up in a household “surrounded by a lot of creativity”—her mother is a visual artist and her father was a teacher and writer—and she picked up dance at age 3. She traces the inspiration for her Rolling Dance Chair to that lifelong passion, and to two formative experiences.

When she was 12, Morris’s dad got into a major car accident that left him with brain damage and reliant on a wheelchair. “He had a lot of medical equipment and a lot of different types of wheelchairs,” she remembers. But none of his devices were particularly user-friendly. His standard manual wheelchair, for instance, “kind of boxed him in,” she says.

Helping her mother maneuver her father and observing the strain that his disability put on her parents’ relationship got Morris “thinking about these kinds of devices as interfaces between people, and how can they be more organic, more conducive to human interaction.”

Then in 2001, a few years after Morris was hired at USF, she began working with a group of dancers with disabilities. “Most of the individuals that I was working with were wheelchair users who had not a lot of control in their lower body but had a fair amount of control in their upper bodies,” she recalls, “so I started thinking a lot about how this device was supporting their performance or, in some cases, inhibiting it.”

In 2006, Morris received a grant from USF to develop an accessibility chair designed for dance. The first thing she did was order several Segways for research purposes. The Segway, she says, “seemed to be the closest idea at the time” to the device she had in mind: a chair that moved in response to subtle body cues. If a user’s arms and hands were free, they “would be more available to interact with other dancers or do other movements,” says Morris.

Student engineering groups at USF helped Morris build what she calls a “rough draft” of her concept: a retrofitted power chair with sensors built into the seat that caused the device to move forward when a user tilted in that direction.

For the next iteration, Morris recruited a professional team consisting of a programmer and a designer and fabricator. Together, they built the first real prototype, which debuted in May 2013.

At first blush, the Rolling Dance Chair looks like a sleeker, futuristic version of a power chair. The seat, reminiscent of an Eames design and imported from Italy, is a rounded piece of translucent plastic that “catches the light well,” says Morris. “I think there’s kind of an elegance about it.”

The seat can move up and down and swivel independently from the chair’s black aluminum base, which contains indentations that can be used as handgrips or footholds, and that enable other dancers to interact with the person in the chair.

The base obscures the chair’s four wheels so that “there’s no interference with costume or dress,” says Mark Rumsey, Morris’s designer and fabricator, who’s based in Southern California. The precise configuration of those wheels, combined with rollers on each tread, allow for the chair’s omnidirectional movement, which the user operates through a Samsung Galaxy smartphone.

When a user straps the phone to her back, for example, and leans in one direction, the phone’s motion sensors—a gyroscope, an accelerometer, and a magnetometer—collect data on her position and movement. “We’re tapping into the natural motion sensor technology that already exists in a phone,” says Morris.

A filtering algorithm cleans up the positional data, which is then relayed to sensors in the chair’s base, “where all the magic happens,” says Neil Edmonston, who did all the programming. After some quick, complex computing, the chair deciphers the sitter’s movement and mirrors it.

“For [the chair] to move, you have to move first,” says Edmonston, who runs a consulting service in Pensacola, Florida. But “it happens in such a short period of time that it looks seamless.”

The degree to which a user leans governs how quickly the chair rolls. “For instance, if I move a little bit, I’ll move slowly. If I lean more, I’ll move faster,” explains Edmonston. “So, it allows you to have a very intuitive and fully controllable type of movement.”

The Rolling Dance Chair also has an alternative mode: A bystander—say, a dancing partner—can operate it, either by tilting the phone or by tracing her hand across the phone’s screen, using it as a “touch-joystick kind of control,” says Morris.

Dancer Luca “Lazylegz” Patuelli tested that mode a couple weeks ago, when he was visiting USF for an integrative dance festival called A New Definition of Dance (which Morris founded). Lazylegz is a b-boy (what popular media often calls a breakdancer), and he incorporates crutches into his routines—he was born with arthrogryposis, which is characterized by limited range of motion in multiple joints.

While a partner operated the Rolling Dance Chair’s control, “I was doing some different designs and different angles using my crutches while I was moving,” he says.

Putting the control (quite literally) in a partner’s hands “adds a completely different element for a spectator, but also for the dancer themselves,” says Lazylegz. Not only do you have to trust your partner, “but you also have to trust the technology.”

Morris and her team are now working on a second prototype of the Rolling Dance Chair in the hopes that they’ll be able to license it commercially. “I’ve been in communication with several different wheelchair companies, and so we’re making progress that way from a business perspective,” she says.

Updates entail motorized height change and seat rotation (these features are manually operated in the current prototype), as well as a new set of wheels in an improved configuration that will ensure smoother, quieter rolling across uneven surfaces.

Dwayne Scheuneman, founder of REVolutions Dance, Inc., an inclusive dance company based in Tampa, has helped Morris test her chair since the beginning. Scheuneman, who has a spinal cord injury, prefers his manual wheelchair because it enables him to perform certain modern dance moves, such as tipping over to the floor and pushing back up again.

But for some dancers, he says, the Rolling Dance Chair could be the device they’ve been waiting for. “Any manual chair is not right for everybody. Any current power chair isn’t right for everybody. So, Merry Lynn’s Rolling Dance Chair, it isn’t going be right for everybody,” says Scheuneman. But “there are people who are going to love it, and it’s going to be so useful”—for dance, but potentially for everyday life, too, he says.

As Morris and other dancers explore the Rolling Dance Chair’s possibilities, they’ll add to a growing repertoire that people with disabilities have been experimenting with for a while.

“I do think that improvements can be made in the wheelchair and in other mobility devices for dance for peak performance, and especially if we want to get to higher levels of artistry,” says Morris, “but people are dancing in the things that they have, in the bodies that they have, and I’m very much a supportive advocate of people dancing however and in whatever creative modes they can.”

*This article was updated on November 1, 2016 to clarify that seating and mobility specialist Mary Ellen Buning hasn’t seen the Rolling Dance Chair in person but watched a video of it.

Julie Leibach is a freelance science journalist and the former managing editor of online content for Science Friday.