A Butterfly’s-Eye View: Aloft in a Balloon

Camille Flammarion’s balloon excursions afforded a new perspective on the world.

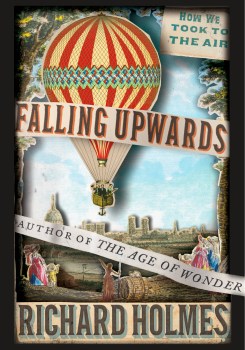

The following is an excerpt from Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, by Richard Holmes.

[Camille] Flammarion had a wonderfully fresh eye, and he constantly picked out and delighted in unusual phenomena. As he put it, “It seemed rational to ‘go and see’ for myself what is being done in these higher regions.” Once, while aloft , he noted a strange cloud of dust over Paris, “whitened by the rays of the sun,” and thought at first that it was ordinary city pollution. Then he realised it was kicked up by the exceptional crowds visiting the National Exhibition, far below. As he put it, the democratic air “bore witness to the excitement and pleasures of ordinary people”: running feet, dancing horses’ hooves, and flying carriage wheels over the gravillon. Another time, over green fields in the evening, with the sun low and behind him, he saw the balloon shadow ‘completely surrounded by a yellowish white aureole, such as is seen painted round the heads of saints’. The air beatified the balloon with a halo.

He delighted when he entered a thick cloud with a particularly high hygrometer reading, and suddenly found himself in the middle of a concert hall in which “excellent orchestral music” was playing. It turned out that the dense, humid atmosphere was especially suitable for collecting the sounds from a village band playing in the central square of Boulainvilliers, a little country town lying invisible 3,280 feet below.

He noticed the different colours of river waters, due to different soils, and how they did not always immediately intermingle on meeting: “The water of the Marne, which is yellow now as it was in the time of Julius Caesar, does not mix with the green waters of the Seine, which flows to the left of its current; nor with the blue water of the canal which flows to the right.” The result became a single tricolour of river water which flowed for several kilometres, yellow in the centre and green and blue on either side. “If travelling in balloons were commoner than it is at present,” he remarked pointedly, “what facilities it would confer on topography and surveying in general!”

Flammarion carefully observed other creatures in the air, besides birds or his own carrier pigeons. He glimpsed moths, beetles, spiders, but especially butterflies: “Butterflies hover round the car of the balloon. Until today I imagined that those little things passed their short existence among the flowers of the fields, and that they never rose to any great height in the air. But in fact they rise higher than any of the birds of our forests, and soar to many thousands of metres above the ground . . . And another thing strikes me: they do not appear to be frightened by the balloon as birds are. Why is this?”

Excerpted from Falling Upwards, by Richard Holmes. Copyright © 2013 by Richard Holmes. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Richard Holmes is a writer and biographer based in Norwich, England. He’s the author of Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air (Pantheon, 2013), among others.