You’ve Heard Of The Microbiome—Welcome To The Mycobiome

12:10 minutes

You’ve heard of the microbiome, the community of bacteria, viruses, archaea parasites, and fungi that live in our bodies. But that last member of the group, fungi, get a lot less attention than the others. And perhaps that’s unsurprising. After all, bacteria outnumber fungi 999 to 1 in our guts.

But now, scientists are beginning to piece together just how important fungi truly are. Disruption in the fungal balance can play a role in the development of Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel disease, celiac disease, colorectal cancer, some skin diseases, and more.

Host Flora Lichtman talks with Dr. Mahmoud Ghannoum, microbiologist and professor at Case Western Reserve University’s School of Medicine, who has dedicated his career to studying the fungi in our bodies, and coined the term mycobiome over a decade ago.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Mahmoud Ghannoum is a microbiologist and professor in the School of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. When I hear microbiome, I think of the billions and billions of bacteria that call my body home.

But the microbiome is more diverse than that. It includes viruses and parasites and fungi. And that last group doesn’t always get a lot of attention. Partially, it’s a numbers thing. Fungi are outnumbered by bacteria about 1,000 to 1 in the microbiome.

But even if they’re a smaller sliver of the population, according to my next guest, that does not mean our fungal friends and foes are less important. When your fungal Feng Shui is off, things can go afoul. Fungi can play a role in Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel, celiac disease, colorectal cancer, and more.

Our next guest has been banging the drum for fungi for many years. Over a decade ago, he coined the term mycobiome to shine a spotlight on these misunderstood mycelium. Dr. Mahmoud Ghannoum is a microbiologist and Professor at Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, based in Cleveland, Ohio. Welcome to Science Friday.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Thank you for having me.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Let’s start with the basics. How do you define the mycobiome?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: As you mentioned, in our body, there are microbes that live in and on our body, on the skin, in our gut, all over the place. One important community of these microbes is the mycobiome. And as you know, mycology is the study of fungus. So we coined the term mycobiome to refer to the fungi that live in our body.

FLORA LICHTMAN: No one had coined that term before.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Nobody have coined this term before us. And really, it came from the fact that, for many, many years, I worked with fungus. And I always knew that bacteria and fungi, they interact together, and they play together. So about 15 years ago, when people were talking about the microbiome, they talk about bacteria. I told them, no, no, no, you really need to talk about fungi as well or the fungus that live in our body. And that’s where I thought it would be a good idea to differentiate the bacterium, which is the bacteria, from the mycobiome, which is the fungus.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Did it work? Did people heed your call?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: It’s so funny you asked this question. For a long time, people did not listen. I wrote an article in 2010 that we should look at both of these communities, and nobody listened. 2016 I also wrote another article in The Scientist saying the mycobiome, basically the ignored Kingdom.

And lo and behold, I published a paper after that to look at the microbes that live in the gut of Crohn’s disease patients. And I showed that not only bacteria is there, but also fungi are there. And they really interact together, and they help each other. After this, people start reaching out to me asking about the fungal community.

And really, they needed guidance, how we can help them to rebalance. And that’s where people start to take really the mycobiome into consideration. In fact, 2021, also the National Institute of Health opined at that time to say, yes, we really need to look at not just bacteria but about the other communities out there. And that’s really pleased me tremendously because it took them a decade, but they figured it out at the end.

FLORA LICHTMAN: [LAUGHS] Well, how do fungi and bacteria interact with each other in the microbiome?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: What happens, when they are together, you can imagine they are not like in suspension. They stick together. They adhere to the tissue in our gut, the gut lining, for example.

And then what they do, they start secreting some chemicals or metabolites that can change their behavior. In fact, to give you a specific example, we found that E. coli and Serratia marcescens are two bacteria. They interacted with Candida tropicalis, which is the fungi, and they formed what we call biofilm. You know what a biofilm? It’s like the plaque in our teeth.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I was just going to say, yes, I know about it from my teeth.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Exactly. But nobody described them in our gut , how they interact together to really cause our issues with Crohn’s disease, for example.

FLORA LICHTMAN: In a biofilm in your gut, what should I be picturing?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: The best way to imagine a biofilm, it’s like a jello. Inside this jello, you have M&Ms or raisins.

FLORA LICHTMAN: [LAUGHS] You’re speaking my language, Mahmoud.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: [LAUGHS] So you have the jello is the matrix. Matrix is what. These raisins and bugs inside the jello produce. It’s made of carbohydrates, proteins, some DNA, and it becomes like a cover, or an area, which protects these organisms.

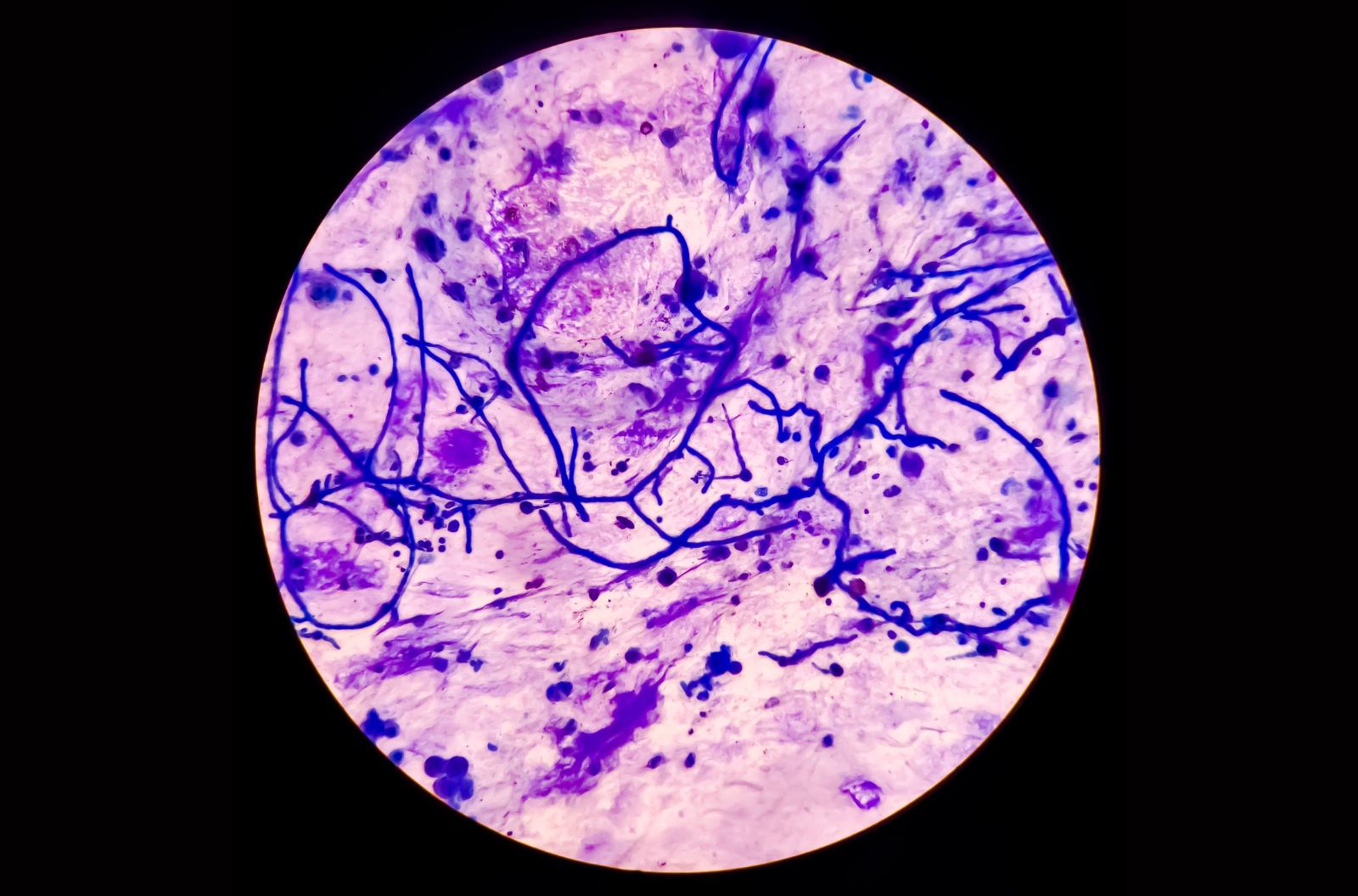

Not only this, when they interact together, these bacteria and fungi, we showed in animal models, as well as in vitro or test tube experiments, that the shape of the Candida changes. So if you have a plaque or biofilm of Candida alone, it’s in the shape of yeast, like Baker’s yeast. When you put them together with the E. coli and Serratia, they form what you call filaments, or hyphae, or like thread like, thread-like material.

And what happens, this thread-like material, they start to poke holes in our gut lining. And that’s why we have leaky gut. And they are protected from antibiotics or antifungals because of the matrix, which we talked about, the jello as well as they are protected against our immune cells. You find the immune cells are unable to go in and kill these bad bugs.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow. So they’re working together in some cases.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Yes.

FLORA LICHTMAN: We hear a lot about how antibiotics wreak havoc on our microbiome. And when I think of that, I think about the effects to bacteria. But has modern medicine changed our fungal makeup?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Yes, definitely. You will laugh at this. I am an old man now. I am 75 next May. I did my PhD or doctorate 50 years ago.

50 years ago, my project was how antibiotics and steroids can affect Candida. In other words, when you use an antibiotic, what happens, you kill not only the bad bugs or the bad germs that are causing disease. We kill also the beneficial one, which keeps Candida under control. So that’s why when you use an antibiotic, definitely it wreaks havoc in your gut balance.

FLORA LICHTMAN: We hear about these good bacteria. Are there good fungi?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Yes, certainly. Thank you for asking this question because a lot of the time people think of fungus are bad thing, apart from the mushrooms, of course. People love those. Now, we have good fungi or good yeast, like Saccharomyces cerevisiae. You remember, Saccharomyces cerevisiae is what we use to bake our bread and make beer. And we found, in healthy people, we have high level of this good yeast or good fungus.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wait If you’re healthy, you have a high level of bread-making and beer-making yeast in your body?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Yes, Yes.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Do we know what these good fungi are doing?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Yes, we know. Of course. Remember, I am a fungi. I know a lot about fungus.

FLORA LICHTMAN: [LAUGHS]

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: So what they do, they can control the ability of Candida to grow.

FLORA LICHTMAN: And Candida is like the fungus we know is associated with yeast infections and thrush. We don’t want that one out of control.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: We don’t want that out of control. But I love the word you said, “out of control.” Why? Because if you look at people in general, healthy people, maybe 50% to 70% of us have Candida in their gut. If it is at low abundance, it’s no problem. We can take care of it because the good guys can keep Candida under control.

The problem starts when we kill these good guys. This gives Candida the opportunity to overgrow. And lo and behold, when it overgrows, believe it or not, what it does, it keeps the good guys down. So as if we killed the policeman and we keep the policeman under control, that is not good for us.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So the beer bread fungus keeps the bad guys under control. What I’m hearing you say is that this is an argument for drinking more beer and eating more bread.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: [LAUGHS] Unfortunately, biology is not as simple as this.

FLORA LICHTMAN: [LAUGHS]

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: I agree with you. Having a beer is great. So you don’t want to take the message from me here that go and drink about five or six beers a night. So yes, having little alcohol is good but not too much of it.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Do we have to worry about antifungal resistance the way that we worry about antibacterial resistance?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Certainly. I tell you something. You are asking good questions. I’m praising you now.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Don’t butter me up. I know what you’re doing here.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: You know why? Because you touched on a topic now which now is becoming hot, the antifungal resistance. We all know about the antibacterial resistance. It’s time to think antifungal resistance.

There was a new fungi that cause infection in the skin discovered in India, which is resistant, highly resistant, to terbinafine, one of the major drugs we use to treat nail infections. And lo and behold, we are starting to see it in the US as well. And there was big interest from the CDC asking people to submit applications to understand what is the extent of really spread in the US. I tell you, this is an area that needs to be addressed because, in addition to antibacterial resistance, we have now antifungal resistant.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Why do you think the mycobiome has been overlooked for so long?

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: Because for a long time, we did not have a lot of fungal infections. It was mainly bacteria. But what happens, we change medicine, the way we practice medicine. I’ll give you a simple example.

When you have cancer, you are treated with chemotherapy, radiation, and all this stuff. And guess what happens? You lower the immunity of the patient. And when a patient has low immunity, this gives the opportunity for fungi to cause infection.

That’s why we call it opportunistic infection. They take the opportunity. When somebody’s immunity is weak, it starts. And that’s why now we are seeing more fungal infection than we used to see, let’s say, 40, 50 years ago.

FLORA LICHTMAN: And so now people are paying attention.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: I hope so.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Thank you so much for this fascinating conversation.

MAHMOUD GHANNOUM: You are most welcome. It’s a pleasure to talk to you.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Dr. Mahmoud Ghannoum, microbiologist and professor at Case Western Reserve University’s School of Medicine, based in Cleveland, Ohio.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.