The Accidental Discovery That Gave Us ‘Forever Chemicals’

10:19 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Jordan Gass-Pooré, was originally published by NJ Spotlight News.

When it comes to PFAS chemicals—known as “forever chemicals”—we often hear that they’re used in nonstick coatings, flame retardants, and stain repellants. But those examples can hide the truth of just how widespread their use has been in modern life.

A new season of the “Hazard NJ” podcast looks at the origin story of PFAS chemicals, and the accidental discovery of PTFE—aka Teflon—in a DuPont laboratory in southern New Jersey. “Hazard NJ” host Jordan Gass-Pooré joins guest host Kathleen Davis to talk about the history of PFAS, their effect on the environment and health of New Jersey residents, and work towards cleaning up the PFAS mess.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Jordan Gass-Pooré is creator and host of the Hazard NJ Podcast, in New York, New York.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: This is Science Friday, I’m Kathleen Davis. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science–

SPEAKER 1: This is KRE–

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: Saint Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: –local science stories of national significance. We’ve talked a lot on this program about the problem of PFAS chemicals, the so-called forever chemicals that are just about in everything in our environment. And we often say something like used in nonstick coatings, flame retardants and stain repellents. But all that traces its history back to the accidental invention of one substance, Teflon. Joining me now is Jordan Gostisbehere, creator and host of the Hazard NJ podcast. The new season looks at the history of PFAS and their role in New Jersey. Jordan, welcome back to Science Friday.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Thank you for having me, Kathleen. I appreciate it.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So remind us again of what PFAS chemicals actually are.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yeah, and it’s interesting that you say PFAS because I usually pronounce it PFAS. But then, when I was recording episode one, I said PFOS, so I’ve had to keep it that way throughout the entire season. They’re a class of thousands of chemicals, so it’s not just 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. There are thousands. And the big kicker about these chemicals, though, is that the ones that we at least know about and the ones that we have researched and that we’ve studied have been linked to numerous health risks. Again, PFAS, there’s thousands of these chemicals. It’s not just one.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So this traces back to Teflon, which was not an intentional invention. Tell me about that.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yeah, I think this story was the most fascinating to me because I saw this season as the beginning of PFAS and the end, hopefully, of PFAS in New Jersey. It started in New Jersey, and our last episode really gets into what’s being done to get rid of PFAS once and for all in New Jersey. And so I actually had no idea that Teflon was discovered in New Jersey until working on this project.

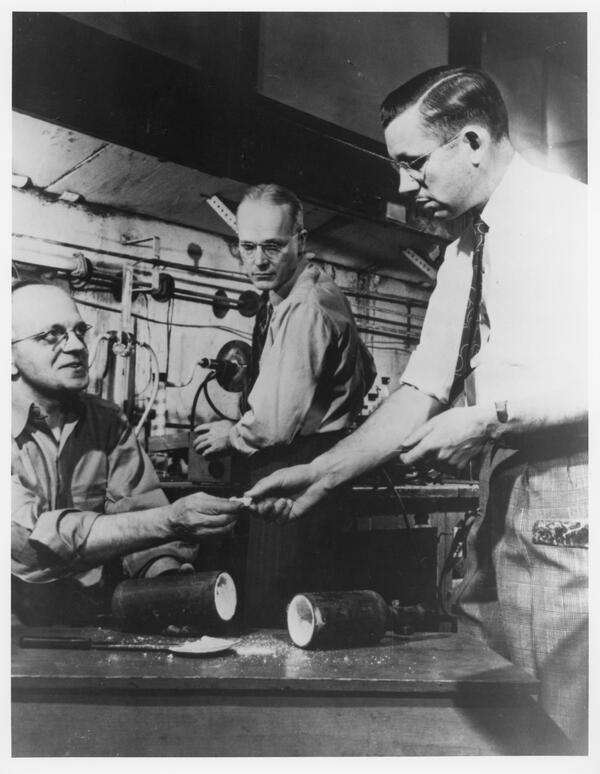

1938, setting the stage here, that in a lab in deep South Jersey, it was Roy Plunkett. He was 27. He was pretty low income kid, grew up in Ohio, and he started working for DuPont. It was a really good paying job, moved to South Jersey. And what he was supposed to be doing at the time of this accidental discovery of Teflon was trying to figure out a DuPont version of freon.

So it was him and his assistant, Jack Rebick. So they’re trying to work on finding a DuPont version of freon, and they’re experimenting with this new gas. And they think maybe we’ll figure something out here. Things aren’t going according to plan. And then one day, they open up this canister and they discover this white powder. And that was the beginning of Teflon.

They started testing this powder, and they realized that it wouldn’t break down. It didn’t break down when it was exposed to heat, electricity, most solvents. And yeah, that turned out to be PTFE, which DuPont later dubbed Teflon.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: OK, so let’s hear this clip from Roy Plunkett.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– I’m proud of my part in this development. I’m proud of the company with whom I worked. I’m proud of what has happened. And most of all, I’m proud of all the benefit to mankind from this original invention. The discovery of PTFE has been variously described as an example of serendipity, a lucky accident, a flash of genius. Perhaps all three were involved.

[END PLAYBACK]

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So it turns out, though, that this didn’t really catch on at first in the industry until the Manhattan Project. Is that right?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yeah, that’s right. So the interesting thing about this was DuPont is also connected to nylon. So nylon, we most often think of it as nylon hosiery, so your pantyhose made out of nylon. And this was right around the kickoff of World War II, when nylon was invented. And that, unlike PFAS, was a very purposeful for discovery. They were looking for stronger fibers. And so they were all concerned about that.

And then comes World War II, and you have this General, General Groves. He was the director of the Manhattan Project. And he had heard through the grapevine about Teflon and how great this new chemical was, and like I had mentioned before, how it’s really difficult to break down. And so General Groves goes to DuPont and says, you’re going to have to ramp up development. And pretty much from what I’ve read, in a nice way of threatening DuPont, saying, if you’re not going to ramp up development, the military is going to take this chemical away from you.

So DuPont said, OK, great. We’ll be able to supply you with enough of this product for all the things that you’re doing, the secret things you’re doing with the Manhattan Project.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow. OK, so after the war, this material found its way into consumer products. And I think the one that most people are going to be familiar with is the Teflon pan, right?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yes. So DuPont released the first Teflon coated pots and pans in 1960. They released that at Macy’s New York City. And they were correct. They kept thinking this was going to be a hit. Sure enough, it was a hit and I found the price of that original Teflon pan that you were wanting to buy at Macy’s in 1960, and it was $6.94, in case anybody was curious about that.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Whoa, that’s fascinating. OK, so let’s fast forward a little bit. It turns out that related materials weren’t just useful in your frying pan. They found other uses, right? Like in firefighting foam.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: They did, yeah. So that first PFAS chemical for Teflon was really resistant to heat and was really hard to break down. And also, with the Manhattan Project and already the US military getting interested in this and using it, we talk about a little bit the Forrestal disaster. It was a big fire on a Navy ship, and this really hit the US Navy very hard. And they kept thinking, like, what could actually have been done to have prevented this disaster? And that’s what was really leading people into the research of we need a better firefighting foam. And the PFAS chemicals fit the bill.

That was one product. But, I mean, PFAS has become so highly ubiquitous that, I mean, even today, when I put on my waterproof jacket to go outside, I was thinking, there’s probably PFAS in that. My mom, when I was a kid, I remember Scotchgarding my shoes, spraying that stuff in the house in front of me. Scotchgard has PFAS in it. They’re in all sorts of everyday products. They’re in fast food wrappers, they’re in face masks, they’re in toilet paper. It’s everywhere.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So, I mean, with things like firefighting foam where you are spraying them everywhere and when you’re washing your Teflon pans, I mean, is that stuff just all getting into the environment?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: It is. And I think one of the interesting things about this is that even thinking about, well, I have these products already, like a Teflon pan, I don’t want to use them anymore. I’m going to throw them in the trash and I’m going to buy pans that don’t have any PFAS or products that don’t have any PFAS in it, because I did my research. OK, you’re throwing it in the trash. Where do those products end up in the trash? They’re going to go to a landfill.

They can’t be recycled. And in that landfill, PFAS will leach out of those products and be able to then go into drinking water systems, go into rivers and aquifers that supply our drinking water. And you have what some of the scientists I spoke with call this PFAS cycle, which is terrifying.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Jordan, I have done that exact thing with my non-stick pan that I got a little too scared of. So you have it in the water and in all these products. Is it in us?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: It is in nearly all of us. And I say nearly all of us, instead of completely all of us, because I imagine that most of us have not had our blood tested for PFAS. I remember one scientist saying too– and this really terrified me– is that PFAS has been found in polar bears. It’s everywhere. You can’t escape it.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And we have a clip here from Graham Peaslee, who’s professor emeritus at the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Notre Dame.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– Gee, we’re finding PFAS in every blood sample, in every blood bank. In fact, you have to go back to the Korean War to find blood that didn’t have it. There’s no blood left in North America that doesn’t have PFAS in it, from cord blood to adult blood anywhere.

[END PLAYBACK]

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So, I mean, you looked specifically at the town of Paulsboro, where researchers from Rutgers have been studying blood samples from residents. What have these researchers found?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Yeah, so the whole purpose of the study is to try to see, is there a link between PFAS and different health conditions? But right now, yeah, that study has not officially concluded.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So we’ll wait to see the results of that blood study from Rutgers. But I mean, this is such an overwhelming issue, it feels like. Is there any hope or signs of progress towards cleaning up this problem?

JORDAN GASS-POORE: One hopeful thing is that earlier this year, for the first time ever, the EPA announced new drinking water standards for five PFAS chemicals in drinking water, which was huge. What I’ve been told, because there is some hesitation– the fear that some of these things might be rolled back and it might be left up to the states to figure out the PFAS contamination sort of on their own– hopefully, they won’t be rolled back. New Jersey was sort of at the forefront in 2018 of setting their own standards, and that I don’t think it would be a bad idea if other states also decided to set their own standards and follow suit, especially more stringent standards.

I don’t want to get doom and gloomy, but I think the EPA announcing those drinking water standards for the five chemicals is a good step in the right direction, but it looks like it’s going to be chemical by chemical. So again, PFAS, there’s thousands of PFAS chemicals, and the EPA is only regulating now five. Hopefully, maybe we might follow suit, like in Europe where they’re considering drinking water standards for the entire PFAS family and other families of chemicals instead of doing it chemical by chemical.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Jordan Gass-Poore, creator and host of the Hazard NJ podcast. Thanks so much for being with us today.

JORDAN GASS-POORE: Thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.