How Blind Women In India Are Detecting Early Breast Cancer

8:24 minutes

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide, just behind lung cancer. And the earlier a breast tumor is found, the more likely it is that the person survives their diagnosis.

An international program called Discovering Hands trains blind women to detect even the smallest lumps and bumps through breast exams. The idea is to leverage the blind examiners’ sense of touch, which may be more acute than sighted people’s, to feel for breast abnormalities and, hopefully, catch cancer in an early stage.

Discovering Hands has a cohort in India, a country where only around one in every two people diagnosed with breast cancer survive, and imaging equipment can be expensive or hard to come by.

SciFri producer Rasha Aridi talks with science journalist Kamala Thiagarajan, who reported on Discovering Hands’ program in India for NPR’s global health blog, Goats and Soda.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Kamala Thiagarajan is a science journalist based in Madurai, India.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: This is Science Friday. I’m Kathleen Davis. Breast cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide, just behind lung cancer. And the earlier a breast tumor is found, the more likely it is that the person survives their diagnosis.

An international program called Discovering Hands trains blind women to detect even the smallest lumps and bumps through breast exams and to hopefully catch cancer in an early stage. There’s a cohort in India, because there only around one in every two people diagnosed with breast cancer survive. SciFri producer Rasha Aridi is here with more.

RASHA ARIDI: Thanks, Kathleen. To learn more about the Discovering Hands program in India, I spoke with science journalist Kamala Thiagarajan, based in Madurai in Southern India. She reported on this for NPR’s global health blog Goats and Soda. Kamala, welcome to Science Friday.

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: Thank you so much for having me on.

RASHA ARIDI: So, Kamala, what is Discovering Hands, and where did it start?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: The Discovering Hands program started in Germany. And it was founded by a German gynecologist, Dr. Frank Hoffman. And he just wanted to set up the program as a means of helping doctors out, doctors who were having really crowded waiting rooms and didn’t have time to do thorough breast examinations. So he wanted to train women to be able to do it for them, someone to help them out. So that’s how it started. The intention was to catch breast cancer cases early.

RASHA ARIDI: Right. So why does this program train blind women specifically to detect breast cancers?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: So Dr. Hoffman was wondering why he was seeing so many women come in with stage III breast cancer at a time when he couldn’t really help them. And I think that weighed heavily on him. So when I spoke to him, he told me that doctors needed help because it was a failure of the health care system that they were catching women so late in the day when they couldn’t really help them. And so what he wanted to do was train people to help these doctors catch these cases early.

And when he was wondering whom he should train, he remembered there were so many studies that said that blind people had a heightened sense of perception. And so he thought, well, maybe I could use that heightened sense of perception and train these women to catch breast cancer early. And so that’s how the idea started.

RASHA ARIDI: Very cool. So basically, there’s some research that suggests blind people might be more in tune with their other senses, like touch, than sighted people because that’s how they navigate the world. So the idea is to put that to use in medicine through giving breast exams?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: Absolutely.

RASHA ARIDI: So how do the examiners conduct the breast exams?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: They use skin-friendly braille tape. And they tape it on the chest. And then they divide the breast into zones. They use their fingertips and probe and try to find if there are any small lumps that need to be brought to a doctor’s attention. And so if they find something that needs more attention, then they flag that.

So the examinations take about an average of 45 minutes. And this is the kind of time that doctors don’t have today to give to their patients. But these women have been really, really successful in finding even the smallest of tumors.

RASHA ARIDI: Yeah, so how good are they at detecting lumps and bumps?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: They have been surprisingly really good at detecting lumps that medical practitioners and patients themselves miss. They can find bumps 30% better than doctors, even before it shows up on imaging scans. So these are really, really tiny lumps. And it’s thanks to their perception that they’re able to detect it so early.

And there are doctors who spoke to me for this project. And they said that once they’re sure that the medical tactile examiners, as they’re called– once they give it the all clear and they go ahead, they said there’s absolutely nothing more that we can do. We’re very satisfied that they’ve been thoroughly checked.

RASHA ARIDI: So it seems like a win-win across the board, then, for doctors and patients?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: Oh yes, it’s absolutely a win-win, and also for the women themselves. Visually impaired women in India struggle to find jobs. So this is one area where they can excel. And it gives them a lot of dignity.

RASHA ARIDI: Yeah. On that note, you spoke with some of the women in this program. What did they share about their experiences? I mean, why do they choose to do this kind of work?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: They said that they were very scared at the outset of being responsible for a woman’s life this way or a woman’s health. But then they finally found that, with time and with the training, they were confident enough to do it.

The very first thing that they had to learn was mobility training, because usually, in India, visually impaired women don’t navigate things alone. There’s always someone to help. So they said that the National Association of the Blind here that coordinates this program, it gave them mobility training first. And that was really helpful.

So now they can walk to their hospitals where they’re working with a cane. And that gives them a lot of independence. And then the fact that they’re helping save lives– the practitioner that I spoke to said that it’s giving them a lot of joy.

RASHA ARIDI: That’s beautiful. I want to go back to some of the research that’s been done. Do we know if the tactile examiner’s work has led to better survival outcomes?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: It has definitely led to better survival outcomes. But I think that a lot of the work in India still needs to be examined. It still needs to be recorded. The program is just starting out in hospitals in India. So we should, in the years to come, be able to have a clearer picture of how much it’s helping.

But at this point, we have about 75,000 deaths a year thanks to breast cancer in India. And a lot of this breast cancer is being caught in the later stages. So I think that just the very fact that they can catch tumors early will be saving lives.

RASHA ARIDI: Right. And on that note, in your reporting, you write that in India, only about one in two people survive breast cancer. Why is that rate so high?

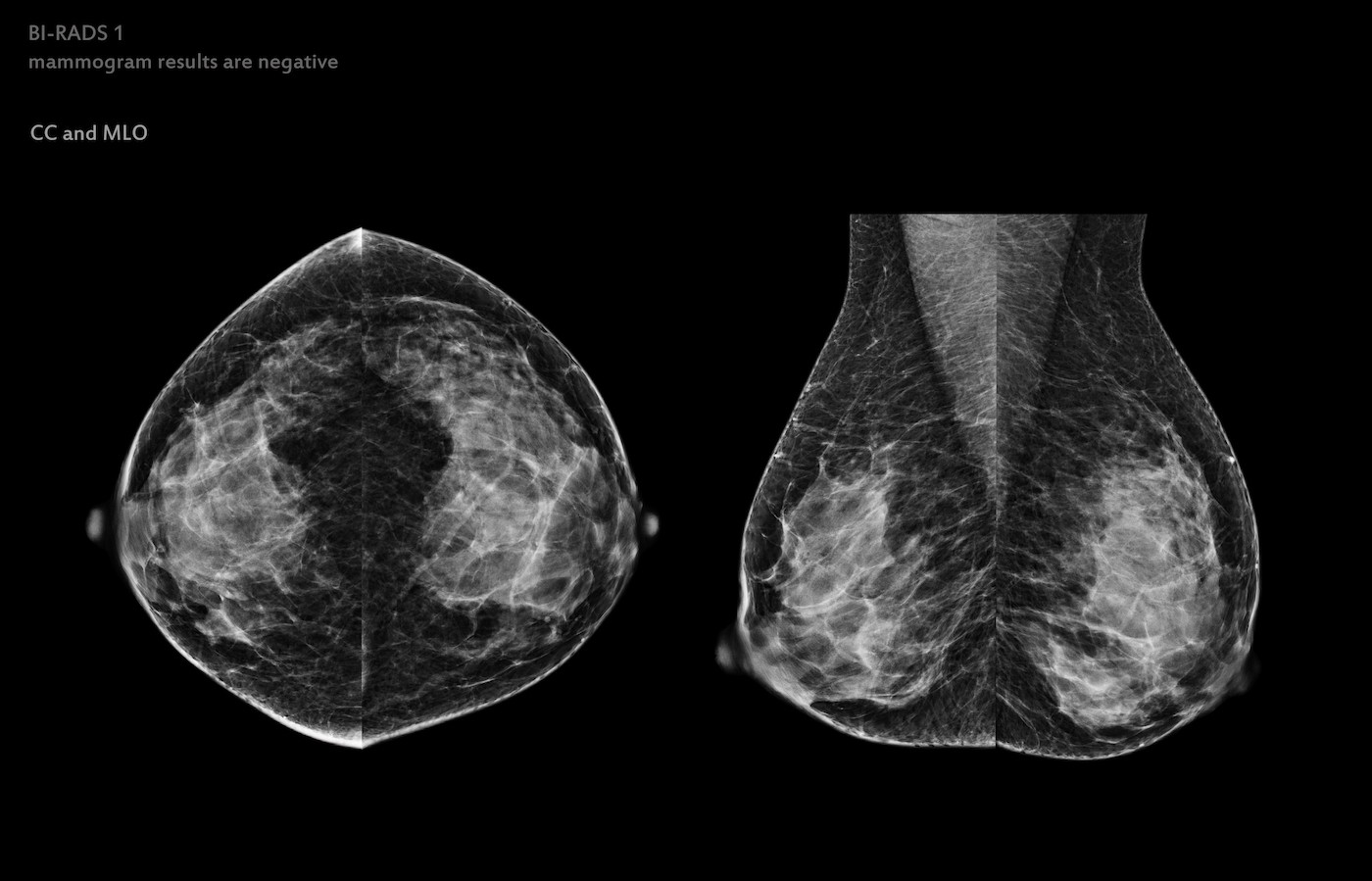

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: Well, for one thing, we have a shortage of mammograms. And for another, especially in our rural centers, if you want to go to a hospital that has a mammogram, it has to be a multi-specialty hospital. And that might involve considerable travel.

And also, the women involved, they are deeply conservative. They may not agree or may not like or be comfortable with someone checking their breasts. And so in this way, the program is also helped because the women who are patients here who are being checked have shown greater trust in these medical textile examiners. They feel less shame in being able to get checked up.

RASHA ARIDI: As you said, so this program isn’t a substitute for having imaging equipment and trained physicians. But it’s more so just another tool to help catch cancer early, right?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: That’s right. It’s not a substitute. What I think it does is that it saves time for doctors. And it ensures that women are caught at the earlier stages rather than when it’s too late and when nobody can do anything about it, because that’s just so heartbreaking. One of the reasons that doctors were seeing cancer at such a late stage was that women are self-reliant, right? So they check out their own breast. That’s what we’ve been asked to do. But then you can’t often rely on that.

So the fact that this program provides you with that support, someone who’s trained in the anatomy of the breast, someone who would be able to identify it, who has a heightened sense of perception, I think, in many ways, that’s a better deal. So yes, the idea would be, yes, we should have more equipment, but it’s just practically not possible.

RASHA ARIDI: So, Kamala, what are you hoping that readers and our listeners take away from your reporting?

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: I’m hoping that readers take away the importance of preventative health care. It’s so important not just to put out a fire, but to prevent it from happening in the first place. And I hope that they’ll be more aware of their bodies because that could save us a lot of grief and pain and time at the end of the day.

RASHA ARIDI: Kamala, thank you so much for your reporting and for talking to me today.

KAMALA THIAGARAJAN: Thank you so much for having me on.

RASHA ARIDI: Kamala Thiagarajan is a science journalist based in Madurai, India. And I’m SciFri producer Rasha Aridi.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.