The Clean Air Act Has Saved Millions Of Lives—But Gaps Remain

24:46 minutes

In the 1960s, the urban air pollution crisis in America had reached a fever pitch: Cities were shrouded in smog, union steelworkers were demanding protections for their health, and the Department of Justice was mounting an antitrust lawsuit against the Detroit automakers for conspiracy to pollute.

But all that changed when Richard Nixon signed the Clean Air Act of 1970. The law set national limits for six major pollutants, established stringent emissions standards for vehicles, and required the latest pollution-limiting technology for industrial facilities. It was widely recognized as innovative, landmark legislation because it was evidence-based, future-proofed, and it had teeth.

Since the Clean Air Act took effect, emissions of the most common pollutants have fallen by around 80%. The law has saved millions of lives and trillions of dollars. An EPA analysis showed that the Clean Air Act’s benefits outweigh its costs by a factor of 30. Thanks to this policy, the United States enjoys some of the cleanest air in the world.

But five decades on, has the Clean Air Act protected everyone? And can a policy designed for the problems of urban, mid-century cities protect our health in the face of climate change?

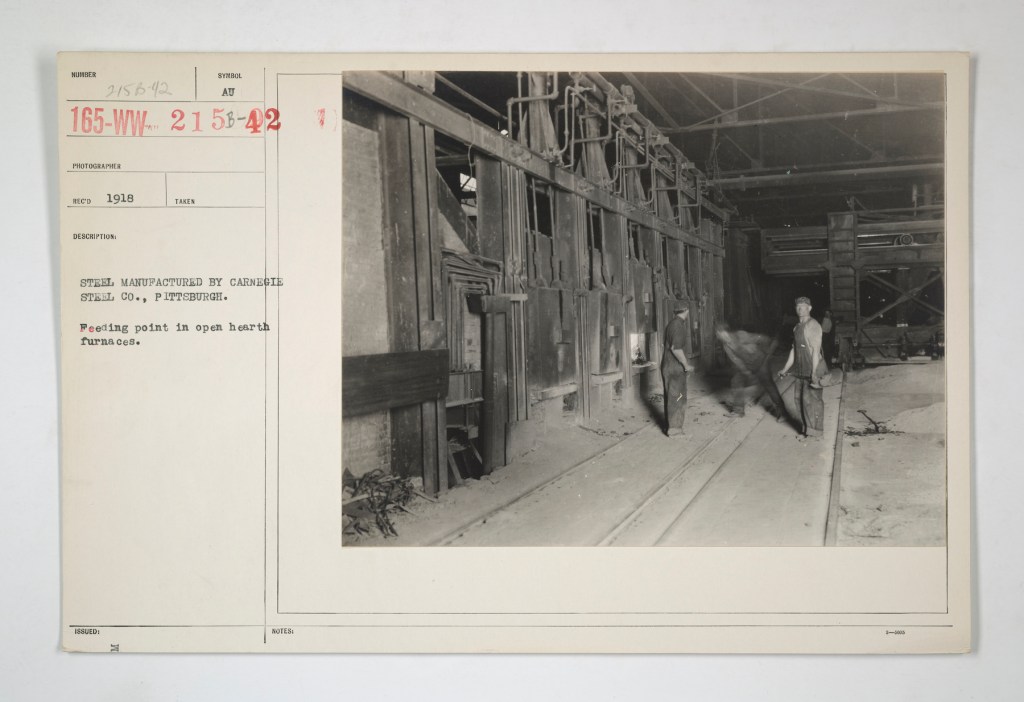

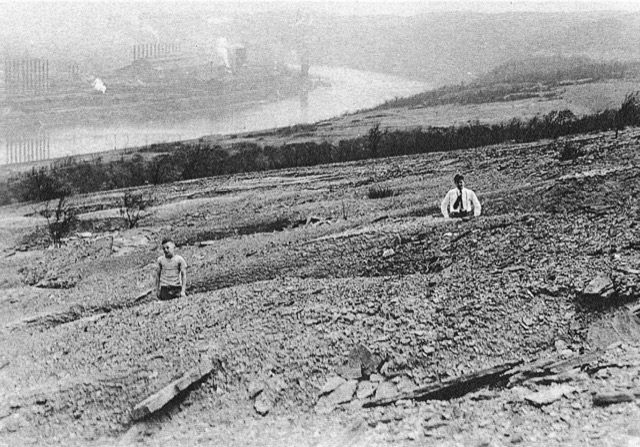

In many ways, the story of the Clean Air Act starts in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, decades before the federal law was signed. In the 1940s and 1950s, Pittsburgh was the steel manufacturing capital of the world. Steel mills and blast furnaces lined the banks of the city’s famous three rivers, burning bituminous coal from the surrounding hills and pouring dark smoke from brick chimneys and smokestacks.

“[Pittsburgh] was one of the most heavily-polluted places on the entire planet,” says Matt Mehalik, executive director of the advocacy nonprofit Breathe Project.

The smoke and dust hung so thick in the air that they blotted out the sun, and the city had to light streetlights in the middle of the day for people to conduct their business in town. Metallic ash settled on homes and stripped paint from residents’ cars. Even hanging laundry to dry on clotheslines was a risk.

“Sometimes you’d look up and you’d run out and you’d take the wet clothes back off the line because you can see the soot and stuff coming in,” says Art Thomas, a long-time Pittsburgh-area resident and former employee of U.S. Steel. “If you didn’t get them off the lines, you had to wash your clothes again.”

The pollution was considered the price that residents had to pay for Pittsburgh’s prosperity, but the public health effects weren’t well understood yet.

Then, in 1948, a wake-up call came from a small milltown called Donora in a river valley south of Pittsburgh. A blanket of warm air, known as a temperature inversion, settled over the river valley like a lid, trapping cooler air—and air pollution from Donora’s industrial plants—close to the ground for five days. By the time the inversion broke and the smog lifted, 20 people had died, and another 6,000 had been sickened out of a town of 14,000.

“It was a truly horrific watershed moment in the history of the United States,” Mehalik says. “That Donora smog incident … set into motion various efforts to control air pollution.”

The following year, in 1949, Allegheny County, where Pittsburgh is located, adopted its first air pollution control law. Over the 20 years that followed, much of the thick, visible smoke in the city cleared—and regulators honed new expertise in air pollution control. The results were dramatic: In 1949, an average of 170 tons of dust was falling on every square mile in Allegheny County each month. By 1969, that number fell to 38 tons.

“A lot that went into the policies that were set by the EPA when it was created in the 1970s grew from that experience trying to tame pollution here in Pittsburgh,” Mehalik says.

While many experts tout the Clean Air Act as one of the most successful environmental policies in the history of the United States, it is also widely acknowledged that it has failed to address the pollution hotspots in many communities of color and high-poverty neighborhoods.

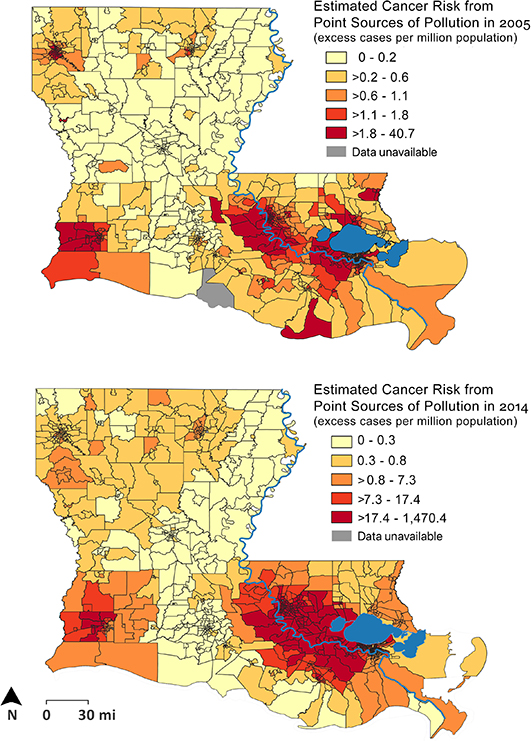

Perhaps the most well known of these is an area dubbed “Cancer Alley,” along the Mississippi River, between Baton Rouge and New Orleans in Louisiana. It’s a stretch of 184 river miles where more than 300 industrial facilities, most of them petrochemical plants, emit hazardous air pollutants. One of the most significant of these is ethylene oxide, a colorless gas used to make products like plastics and antifreeze. It’s a known carcinogen that increases the risk of blood and breast cancers.

Dr. Kim Terrell and Gianna St. Julien are researchers at the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic and co-authors of a 2022 study that linked higher cancer rates to pollution in Cancer Alley. Their research found cancer rates 35% to 40% higher than the national average in some communities. It affirmed what local residents had been saying for decades.

“People have always been saying, ‘Hey, where there’s pollution, there’s cancer,’” Terrell says. “And our study confirms that, yes, where there’s pollution in Louisiana, there’s cancer.”

Lisa Jordan directs Tulane’s Environmental Law Clinic. She says the reason hotspots like Cancer Alley can exist is because “there’s just not really a program in the Clean Air Act that’s specifically designed to monitor and protect every community from breathing toxic air.”

The Clean Air Act has two main ways of addressing pollution. The first is the National Ambient Air Quality Standards program. It requires state, local, and tribal air agencies, which are responsible for implementing the Clean Air Act, to monitor and limit six common pollutants, like lead and particulate matter, in their ambient air. Under this program, pollution standards are clear, monitoring methods are well-established, and compliance is relatively straightforward: A region either meets the standard, or it doesn’t. If it falls short, it has to submit a special plan to the EPA showing how it will comply. If that fails, it triggers sanctions.

The second big way the Clean Air Act addresses pollution is by limiting emissions of 188 less-common “hazardous air pollutants,” largely from major industrial facilities. The approach is two-pronged: First, the EPA requires facilities to use the latest and best pollution control technologies. Then, it looks at what health risks remain after those controls are in place, to determine if more stringent standards are needed. But, unlike with the six common pollutants, hazardous air pollutants are not continually monitored in the ambient air.

Terrell says that may make it possible for there to be dangerous concentrations of these hazardous air pollutants.

“There is no substitute for air monitoring in communities because you can have control technologies that don’t work as well as you thought, or you could have leaks or other sources of fugitive emissions that you’re not accounting for,” Terrell says. “So you don’t know what people are exposed to unless you actually measure that exposure.”

That said, hazardous air pollutants are notoriously hard to measure. But recently, environmental engineers at Johns Hopkins used a mobile lab to measure actual concentrations of ethylene oxide in Cancer Alley. They found levels of the gas 10 times higher than EPA estimates–and a thousand times higher than what’s considered safe for long-term exposure.

The Clean Air Act was designed to clean up urban air pollution emitted from smokestacks and tailpipes. So events like wildfires present a problem. And as wildfires have increased and the wildfire season has gotten longer, jurisdictions have turned to a carveout to help them comply with air quality standards.

It’s known as the “exceptional events rule,” and it allows air agencies to ask the EPA to grant an exception when there’s a pollution event, like a wildfire, that’s out of their control. The exception allows an agency to comply with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards, even if the measured pollution would have pushed a region over the legal limit.

When an air agency is granted an exceptional event, the pollution attributed to that event remains viewable for research purposes, but it no longer factors into the region’s “design value.” The design value is how the EPA determines if an area is in compliance with pollution limits or not.

Public health reporter Molly Peterson says that in terms of government accountability, that’s like erasing the pollution from the record. She worked on an investigative series for The Guardian about the use of exceptional events, which was published last year. Her team’s analysis found that 21 million Americans live in areas where an exceptional event has allowed regulators to report that air was cleaner than it was. And it’s likely trending upwards: In 2016, air agencies across the United States flagged 19 wildfires as potential exceptional events. In 2020, they flagged 65.

“It just seems like it might be worth counting,” Peterson says of the air pollution that’s deemed an exception. “If nobody’s responsible for an airborne problem, then no one’s going … to apply more resources to it.”

Peterson believes new legal frameworks may be necessary to address poor air quality driven by climate change.

“The Clean Air Act is still this absolutely amazing piece of legislation, without which we wouldn’t be breathing and without which my skies in Los Angeles wouldn’t be clear right now,” Peterson says. “Even so, circumstances have changed, and the law hasn’t been able to take notice of that yet.”

This article was written by Susan Scott Peterson.

Susan Scott Peterson is a climate reporter based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

RACHEL FELTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Rachel Feltman. These days in the United States, we breathe some of the cleanest air in the world, but it wasn’t always that way. Back in the 1960s, air pollution had reached a crisis point. Cities were shrouded in smog, union steelworkers were demanding protections for their health, and the Department of Justice was mounting a lawsuit against the big three Detroit automakers for conspiracy to pollute. Then, in 1970, Richard Nixon signed a landmark piece of environmental legislation, the Clean Air Act.

And over the last five decades, that very same law has regulated cleaner, safer air all over the country. But can a 50-year-old law handle the air pollution challenges we face in 2024? Science Friday’s John Dankosky is here with more. Hey, John.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Thanks, Rachel. I’ve been really interested in this history for a long time because I grew up in a place that was pretty famous for once having some of the dirtiest air in the world, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It’s something that my parents and grandparents talked a lot about, but for as long as I can remember, the air in Pittsburgh has actually been pretty clean. So to find out more about this, I called up Susan Scott Peterson. She’s a climate reporter in Pittsburgh who has been covering air quality for a while now. Welcome back to Science Friday, Susan.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Thanks so much.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, so let’s start with this history and some of these stories about dirty air that my parents told me.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Yeah, so as you mentioned, the air is a lot better now. But I think that the fact that it used to be so bad is, in part, the history of the Clean Air Act. So back in the ’40s and ’50s, Pittsburgh was the steel manufacturing capital of the world. There were, as you know, steel mills and blast furnaces all up and down the riverbanks. And then all these people who worked in the steel mills who lived nearby, they were all burning coal to heat their houses. And so Pittsburgh is down in a river valley, surrounded by hills. And that kind of geography tends to trap pollution.

So between the steel making, and the coal, and the geography, air pollution in Pittsburgh used to be really, truly awful. I talked to one of the old timers here. He’s a man named Art Thomas, and he used to work for US Steel, and he told me what it was like to try to do laundry back then, when the smoke was rolling in from the river valley.

ART THOMAS: Sometimes you looked up, and you’d run out, and you’d take the wet clothes back off of the line because you can shoot and stuff coming in. If you didn’t get them off the line, you had to wash your clothes again.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: And it wasn’t just laundry. The smoke and the dust in the air were so thick that they blotted out the sun, and the city would have to have street lights on in the middle of the day, so people could just see.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I know. I’ve seen some of these photos. But like I said before, the Pittsburgh that I grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, it didn’t really have these problems. So what changed?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: There was this huge wake up call. It was an air pollution disaster. It happened in 1948 in this little town called Donora, south of Pittsburgh. So Donora had a couple of industrial plants. And at the end of October of that year, there was something called a temperature inversion. That’s when a blanket of warm air settles over a river valley like a lid, and it traps colder air and air pollution close to the ground. So this inversion was pretty bad. It lasted for five days.

And so all that time, the pollution from the industrial plants just kept accumulating instead of getting carried away by the wind. And at first, people just kind of went about their business. They held their Halloween parade, and the local high school played their football game. But after a few days of this, the fog of pollution grew so thick that it was hard to see, and then people started dying. By the time this inversion ended, more than 20 people had been killed just from breathing the air. Another 6,000 people got sick, and that’s in a town of 14,000 people.

It was international news, and it made Pittsburgh look bad. This is Matt Mihalik. He’s an engineer and the director of an air quality non-profit called the breathe project in Pittsburgh.

MATT MIHALIK: This actually was a very embarrassing thing for high society people who owned factories here in Pittsburgh, but like to hobnob in high society in New York City. They were viewed as making their money and their influence at the expense of killing people.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: And so in 1949, which was the year after this Donora smog, Allegheny County, which is where Pittsburgh is, adopted its first air pollution control law.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, so this happened about 20 years before the Federal Clean Air Act came along. I guess in some ways, Susan, Pittsburgh was kind of ahead of the game.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Yeah, I guess so. I guess you could say we were so far behind in terms of pollution that we got a head start on regulation and technology. I talked to Sherry Merchand who’s a historian working on a new book of essays about Pittsburgh’s environmental history. And she told me that even before the Clean Air Act was signed in 1970, Pittsburgh had already seen some really dramatic improvements.

SPEAKER: In 1949, an average of 170 tons of dust was falling on every square mile in the county every month. But by mid 1969, that was down to only 38 tons per square mile per month.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: And so Pittsburgh had really developed some expertise. And a lot of the science and regulatory practices that went into the Clean Air Act were developed first in Pittsburgh.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK. Well, that’s good, like the Steelers. That’s something for us to be proud of in Pittsburgh. But let’s fast forward to 1970 now. Richard Nixon signs the Clean Air Act. Talk about how big a deal this was.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: It was landmark environmental legislation. Pollution was a crisis. People cared a lot about it. And then in terms of impact, the Clean Air Act has now been in place for more than 50 years, and the emissions of common pollutants have fallen by around 80%. This law has saved millions of lives and trillions of dollars. There are many, many benefits to society because of the cleaner air we breathe, like less risk of early death, and less illness, and fewer missed days of work.

The EPA has analyzed the benefits of the Clean Air Act, and it’s found that those benefits outweigh what it costs to implement the law by something like a factor of 30. This is Matt Mihalik again.

MATT MAHALIK: It is arguably one of the most successful environmental policies ever enacted in the history of our country.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: And that feels like a really big statement to me. And I should add that multiple people I talked to said something similar about the impact of this law.

JOHN DANKOSKY: It is quite a claim, but it also sounds accurate, too. But Susan, I still don’t really understand how the Clean Air Act actually works. So what can you tell me about that?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: This was one of the big questions I had. And so I went to one of our air monitoring stations here in Pittsburgh.

DAVID GOODE: We can go to the rooftop.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: OK.

DAVID GOODE: So was it 56 steps?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: I met with David Good, who’s the program manager for air monitoring at the County Health Department, which is responsible for Pittsburgh’s compliance with the Clean Air Act.

DAVID GOODE: Here’s some of what equipment looks like on the inside. This would be a Teledyne N500 nitrogen oxides monitor. It measures true NO2, which is a more unique measure.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: There were more instruments than I could count. There were some on the inside of the building, some outdoors on the roof, and some of them were really quite expensive.

DAVID GOODE: This instrument right here, the auto GC, about a quarter million dollars.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: What is an auto GC?

DAVID GOODE: An automated gas chromatograph. And again, that measures, continually measures the volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere. It takes samples.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: So this may be naive, but I guess I didn’t expect it to be so complicated or expensive to measure air pollution.

JOHN DANKOSKY: What exactly do you mean by that?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: OK, so you asked how the Clean Air Act works. One of its programs is the National Ambient Air Quality Standards. That’s how it regulates common air pollutants at a regional level. They’re called criteria pollutants, and there are six of them. They’re common. You’ve heard of them. Ozone and particulate matter and lead are a few examples. And these are common enough that I guess I figured that the air monitoring setup would be just a few small sensors, something that you might see on your kitchen counter at home, not a whole building filled with equipment like a research lab.

But David Good explained to me that, even though they are experimenting with lower cost equipment, they still need the robust, reliable, old school, lab grade stuff.

DAVID GOODE: We have to have very highly reliable information that we can, literally and figuratively, take to a court of law.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: They have to be completely sure of the quality of their data, because of how serious the enforcement of the Clean Air Act is. The EPA sets national standards for these criteria pollutants. And if a region doesn’t meet those standards, it basically gets put on probation. Then they have to submit a special plan to the EPA to show how they’re going to comply with the law. And then if they don’t, that triggers sanctions. And the big stick that they have is withholding Federal Highway funding, which is worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, gotcha. So one thing we haven’t said explicitly is that it’s not just regulation and the Clean Air Act that have cleaned up places like Pittsburgh. During the time I was growing up there, the steel industry just collapsed. A lot of people lost their jobs. There’s just a lot less industry in cities like Pittsburgh. But there are, Susan, still a lot of places where industry pollutes the air. And I know that you’ve done some reporting on a place that’s known as Cancer Alley in Louisiana. A lot of chemical plants there. People live near those facilities. They’ve got higher rates of asthma, and cancer and other diseases. What can you tell us about what’s happening there?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: I really wanted to understand this better, and so I talked to some folks at the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic in New Orleans. They serve clients in Cancer Alley, which is along the Mississippi River in Louisiana between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. Here’s researcher Gianna St. Julien explaining it more precisely.

GIANNA ST. JULIEN: Cancer Alley is a stretch of about 184 river miles, and it consists of over 300 plus industrial facilities along that stretch.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: And they’re permitted to emit some very toxic pollutants. One of the most significant ones is ethylene oxide, which is a colorless gas used to make products like plastics and antifreeze. It’s a known carcinogen that increases the risk of blood and breast cancers. So Gianna was one of the authors of a study published back in 2022 that linked air pollution to cancer rates in Black or high poverty communities there. That study found there were hotspots in Louisiana where the cancer rate was 35% to 40% higher than the national average.

And so this study was significant inasmuch as it was the first to systematically document the link between air pollution and cancer in Louisiana. But it was also basically saying the same thing that people who live in places like Cancer Alley have been saying for decades. Here’s the other author of the study, whose name is Kim Terrell. She’s a staff scientist at the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic.

KIM TERRELL: People have always been saying, hey, where there’s pollution, there’s cancer. And our study confirms that, yes, where there’s pollution in Louisiana, there’s cancer.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: But I guess even though this research seems, in some ways, kind of obvious, it has been really important in terms of making the case to regulators that people in Cancer Alley are exposed to higher levels of pollution than people in other places.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Yeah, that seems pretty obvious. But if the Clean Air Act itself is so great, why exactly isn’t it addressing problems like this?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Yeah, I really scratched my head over this one. So it has to do with how the Clean Air Act works. I was talking earlier about the National Ambient Air Quality Standards. That’s the program that regulates the six common criteria pollutants like ozone and particulate matter in the ambient air. That program is pretty straightforward. The pollution standards are clear, and the monitoring methods are well established. But there’s another part of the Clean Air Act that’s more about regulating some of the less common pollutants, like ethylene oxide.

This category is known as hazardous air pollutants or air toxics. And the main way the law deals with air toxics is by regulating major industrial facilities to use the latest pollution control technologies. And they do that by issuing air quality permits to these facilities. They’re called Title V permits, and they’re very complicated, very technical, hundreds of pages long. And getting them approved involves a lot of back and forth between industry and regulators to work out the details.

Fundamentally, there’s a lot more complexity and a lot more wiggle room in the process. So I think there are good reasons to regulate industrial facilities this way, but a big difference between how air toxics are regulated compared to those six common pollutants is that, unlike with those common pollutants, hazardous air pollutants are not universally monitored year round in the ambient air. And Kim says that places like Cancer Alley need more measurement.

KIM TERRELL: You could have leaks or other sources of fugitive emissions that you’re not accounting for. And so you don’t know what people are exposed to, unless you actually measure that exposure.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: All that said, these kinds of air toxics are very difficult to measure. But earlier this year, there was a study that came out of Johns Hopkins where researchers did figure out how to measure ethylene oxide concentrations in Cancer Alley. And they found levels that were 10 times higher than EPA estimates and 1,000 times higher than what’s considered safe for long term exposure.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So that does sound bad. I know that you’ve met some people who are trying to solve this problem. And for that, why don’t we head back to Pittsburgh? I know that we’ve talked about the steel industry mostly leaving there, but there are still some plants left in the Pittsburgh area. And you actually went to a Title V air quality permit hearing. What can you tell us about that?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Yeah, so in September, I went to this public hearing because I wanted to try to understand a little bit more about how these permits work.

JOANN TRUCHAN: Good evening. My name is JoAnn Truchan. I am the program manager for the engineering and permitting program for the Allegheny County.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: The hearing was for one of the three steel mills left in the Pittsburgh area that Edgar Thompson works, owned by US steel.

JOANN TRUCHAN: Number 0051-0P23A.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: It’s a 150-year-old plant that hung on through the collapse of the steel industry. And it’s operating now under a Title V permit that was issued in 2012. That permit was due to be updated five years later. And now, it’s 2024 and it’s still in process.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Hold it. So this permit has been out of date for a long time. What happened?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: It’s kind of a long story, but I think all of them probably are. But I can tell you that essentially, the Edgar Thompson plant was under investigation for air pollution violations when the permit was due to be updated. So after that was resolved, a draft of the permit was issued, and then another draft came out and environmental groups petitioned the EPA for corrections. And so the public hearing I went to was for comments on the latest draft. And the story that unfolded was probably one that’s familiar in a lot of places across the country. There were representatives from industry.

DREW CRAMER: My name is Drew Cramer. I’m an employee of Chapman Corporation. I have personally been working as a contractor at the Edgar Thomson plant for over 30 years and considered–

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: And they had said the new permit was too stringent, and it could harm economic activity and lead to lost jobs. And then there were activists, many of whom were members of communities living near Edgar Thompson or other US steel facilities in the region.

MELANIE MEADE: Hello, my name is Melanie Meade, and this is the second meeting I’ve come to.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: This is Melanie Meade. She’s a narrative organizer for the Black Appalachian Coalition. And activists and community members like her were asking for more stringent pollution controls.

MELANIE MEADE: It disturbs me to no end that the most affected and most sickly are expected to travel distances to share their pain. Please create a better Title V tool that works for the people. This one currently does not protect our health, and we need people in office who want to protect our public health. Thank you.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So, can I ask you what was the result of this public hearing back in September?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: I mean, it’s just more waiting for now. The county has to take in all the public comments. Then once the new permit is finally issued, maybe there will be a legal challenge. There’s just no way of knowing what the timeline will be. And you have to imagine the same sort of thing playing out in other places, too. In my county, we’ve got 28 facilities with Title V permits, and 10 of them are out of date. And so these years long processes of public hearings and appeals, and revisions, and setbacks, you can just kind of imagine it dragging out in other places.

I had never been to a public hearing for a Title V permit before, but what struck me was that many of the activists there had been showing up to comment on this permit for years. I met Melanie Meade for the first time five years ago, when I first moved to Pittsburgh and was doing my first story on air quality. And five years later, she’s still showing up to public hearings. And so I came to this story really enthusiastic about the success and impact of the Clean Air Act, and I still feel that way about it.

But I’ve also come to feel like we owe so much of that success to people living in front line communities who are doing a lot of this tedious work of showing up to these hearings over, and over, and over again. And it makes the air safer, ultimately, for all of us.

JOHN DANKOSKY: That’s reporter Susan Scott Peterson. We have to take a break right now. But when we come back, we’re going to dig into something that the Clean Air Act didn’t exactly address 50 plus years ago. What happens when out-of-control wildfires cause big air quality problems across the nation? This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky, and I’m speaking with reporter Susan Scott Peterson in Pittsburgh about the Clean Air Act. Since it was signed in 1970, it’s helped to clean up pollution from smokestacks and car exhaust. But what about the new threat to air quality that comes from climate change and wildfires, Susan?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: OK, so this came up early in my reporting because I was wondering the same thing. It was on my mind because earlier this year, the EPA updated the air quality standard for particulate matter. It’s been hard for us in Pittsburgh to even meet the old standard, so I was thinking about how the increase in wildfire smoke was going to make it hard for us and for other places across the country to comply with the Clean Air Act standard for particulate matter.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, so remind me what particulate matter is.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: So it’s basically just tiny specks of soot, but it’s dangerous because it’s so tiny. The air quality people call it PM2.5, which means particles smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter. That’s small enough that 30 of them can fit inside the cross section of a human hair. Basically, the smaller they are, the more dangerous they are, because the smallest particles can penetrate deep into your lungs and pass into your bloodstream. So researchers have known for a long time that PM2.5 exposure causes asthma, and lung cancer and cardiac disease.

But newer research, very scary research, in my opinion, has linked it to neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. And so PM2.5 is produced pretty much anytime you burn anything. And when there’s a wildfire, it’s producing a lot of particulate matter, so much that you can see it in the air.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Yeah, for sure, the last few years, we’ve had these terrible wildfires in Canada. They turn the sky where I live in the Northeast, a terrible color, and it’s hard to breathe, too, Susan.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Yeah, exactly. I remember it the same way. There was a day in Pittsburgh that the air was so hazy that the sun was dimmed, and my six-year-old pointed at the sun and called it the moon.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Oh, no.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: And it was a rare experience for those of us living on the east coast. But people out west have been living with these wildfires for a long time, and wildfire season is just getting longer and longer. And so people are exposed to more and more hazardous air.

JOHN DANKOSKY: But the Clean Air Act itself can’t really regulate wildfire smoke, can it?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: No. But the way it works around wildfire smoke is something I hadn’t really considered before. I talked to Molly Peterson. She has no relation, although she does spell Peterson the same way I do. She is a reporter with Public Health Watch. And last year, she did an investigative series for The Guardian about a loophole in the Clean Air Act.

MOLLY PETERSON: Everyone gets mad when you call it a loophole. Don’t call it a loophole. Just kidding.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: The loophole, or whatever you want to call it, it’s a carve out for what’s known as an exceptional event. And it’s built into the Clean Air Act to accommodate things like dust storms or wildfires. So you can imagine a jurisdiction trying to comply with federal pollution limits by regulating all the stuff that’s happening locally. And then a wildfire happens someplace else, and it throws them out of compliance. So the Clean Air Act allows them to apply for something called an exceptional event. So basically, it doesn’t count against them.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This sounds pretty reasonable, I guess, because this is an event they can’t really control.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Yeah, I thought the same thing at first. But some of Molly’s sources were concerned about it.

MOLLY PETERSON: The whole point is that it’s an exception. It’s excused. It’s erased from the record.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: So Molly found in her reporting that since 2016, exceptional events were approved by the EPA in 20 states, and the number of times that wildfires were flagged as the cause has increased a lot. In California, 166 days of pollution were forgiven over the six years she looked at in her investigation. And when that pollution is forgiven for Clean Air Act compliance purposes, the data makes it look like the pollution never happened.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Hold on. What? Where does the data go?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: OK, so the EPA keeps the original data, and you can still look it up and use it for research purposes, but they exclude it from this number called the design value. The design value is the data they use to determine if, legally, a jurisdiction is in compliance with the Clean Air Act. If it’s not in compliance, like I mentioned before, they have to submit special plans where they might encounter sanctions. But if they are in compliance, they’re in compliance. No further action.

So Molly said this approach keeps decision makers from honestly confronting and dealing with pollution in their regions.

MOLLY PETERSON: There are people who have to go out in wildfire smoke conditions and work in it every single day. We’re not thinking about how people have to adapt to that. And it just seems like it might be worth counting.

JOHN DANKOSKY: But then what’s a way forward with this? Even after hearing about Molly’s reporting, I still don’t understand how exactly a city, or a county or a state could regulate something like wildfire smoke.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Yeah, and I think that’s kind of the idea that Molly is trying to get across with this reporting. She told me that the way she sees it, the legal system just hasn’t caught up to the realities of climate change when it comes to air pollution.

MOLLY PETERSON: Wildfire smoke, PM2.5, the existence of PM2.5 at all is something that the Clean Air Act wants to remove, to eliminate, to get away from. But what if we have to live with it? What if that’s something we have to live with at a certain level? How does the law take those things into account, and acknowledge them and do an honest accounting of it?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: And so all that to say, the Clean Air Act was designed for urban settings, and it was designed for pollution from smokestacks and tailpipes. And it’s possible we might need a new or additional framework to address air pollution in the age of climate change.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So I want to ask you about one other thing. And this also has to do with pollution that can’t be controlled locally. There was a Supreme Court ruling this year that struck down an EPA rule that has to do with industrial pollution that drifts across state lines. What can you tell us about that?

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Right, so that’s the Good Neighbor Plan, which is an EPA rule that was going to require stricter pollution standards for power plants in upwind states if their pollution was contributing to high ozone in downwind states. So you can imagine pollution from your next door neighbor state drifting into your state. And who’s responsible for that? But some of those upwind states challenged the EPA, basically saying it would be too expensive to meet those stricter standards.

And the Supreme Court agreed, and so they’ve temporarily blocked the rule. I guess, in terms of what it means, though, the folks I talked to said they’re just not sure how it’s going to play out yet. The Good Neighbor Rule was new enough that it hadn’t been fully enforced yet, and now there’s going to be a judicial review process.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So because of that, it could be a long time before we know exactly how this all plays out.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: Yeah, it could be. But we’ve been talking about the massive benefits we’ve seen from the Clean Air Act. And despite its shortcomings, I guess I’ve been trying to keep in mind that all of this has happened slowly over more than 50 years. And so I’m trying to have hope that this, too, will change.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Susan, thanks so much for joining me today.

SUSAN SCOTT PETERSON: It’s been my pleasure.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Susan Scott Peterson is an environmental reporter. She’s based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. For more of her story, you can go to sciencefriday.com/cleanair. That’s sciencefriday.com/cleanair. I’m John Dankosky.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.