NASA’s Europa Clipper Heads To Jupiter’s Icy Moon Europa

17:09 minutes

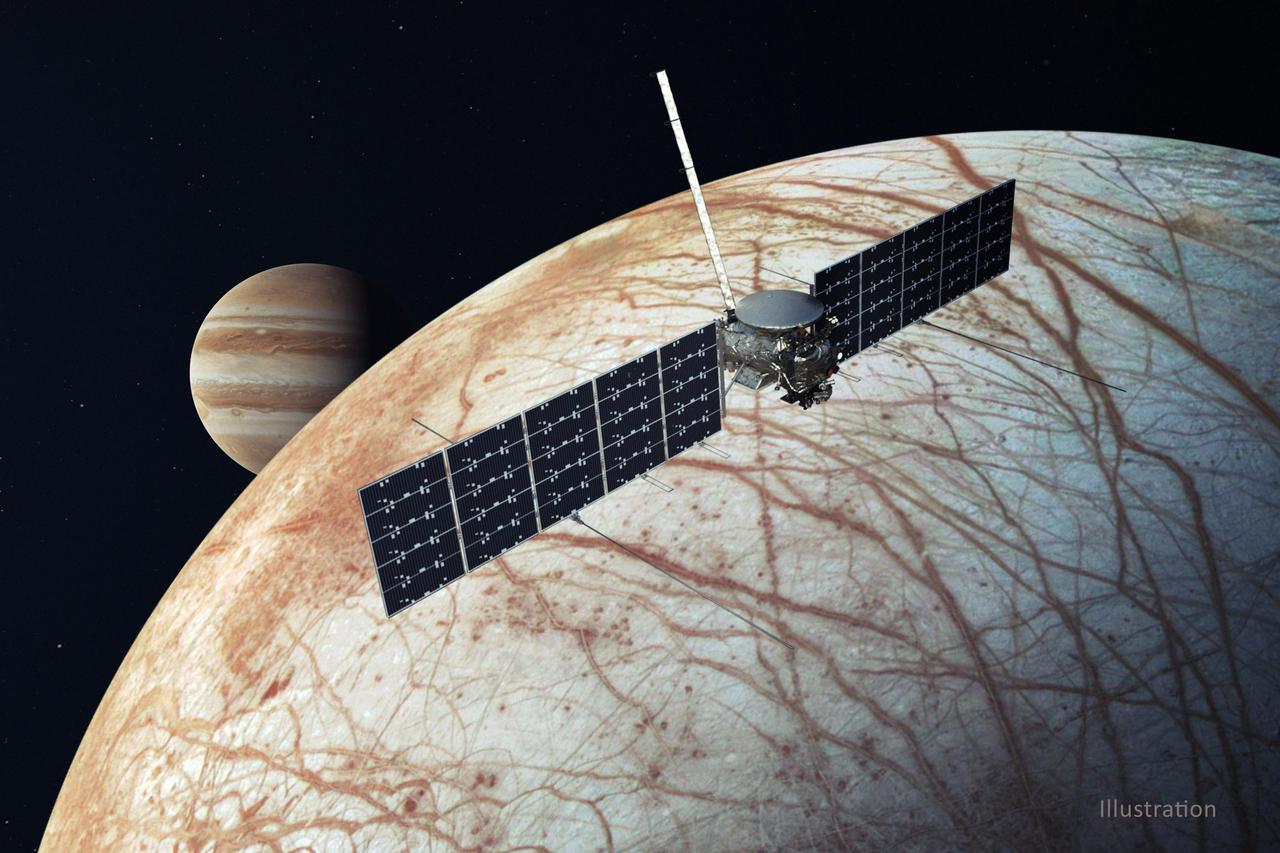

On October 14, NASA launched Europa Clipper, its largest planetary mission spacecraft yet. It’s headed to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, which could have a giant ocean of liquid water hidden under its icy crust. And where there’s water, scientists think there may be evidence of life. The spacecraft is equipped with nine different instruments and will complete nearly 50 flybys of Europa, scanning almost the entire moon.

SciFri producer Kathleen Davis talks with Dr. Padi Boyd, NASA astrophysicist and host of the agency’s podcast “Curious Universe,” about the launch and the excitement at NASA. Then, Ira checks in with two scientists who are working on the mission about what they’re excited to learn: Dr. Ingrid Daubar, planetary scientist at Brown University and a Europa Clipper project staff scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory; and Dr. Tracy Becker, planetary scientist at Southwest Research Institute and a deputy principal investigator for the ultraviolet spectrograph on the Europa spacecraft.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Padi Boyd is an astrophysicist at NASA and host of the agency’s podcast Curious Universe. She’s based in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Dr. Tracy Becker is a co-investigator on the Europa Clipper mission, and a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

Dr. Ingrid Daubar is an associate professor at Brown University and a Europa Clipper Project Staff Scientist at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: This is Science Friday. I’m Kathleen Davis. On October 14th, NASA successfully launched Europa Clipper, a spacecraft that’s now zooming towards Jupiter’s icy moon at Europa. Space nerds are fascinated with Europa because it’s thought to have a massive ocean flowing under its icy crust.

The presence of water is one of the biggest clues for evidence of life beyond Earth, and Europa is one of the most promising places in the solar system to look for life. Later, we’ll get into the science of the mission, but first, here to tell us about the launch, is Dr. Padi Boyd, astrophysicist at NASA and co-host of the agency’s podcast Curious Universe. Welcome back to Science Friday, Padi.

PADI BOYD: Thank you so much for having me, Kathleen.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, tell us about this launch. How did it go?

PADI BOYD: Well, there was some drama, of course. It was actually delayed for a few days due to all of the intense hurricane activity in Florida. So that caused lots of angst, stress, worry, rescheduling, re-planning.

And so a few days later, after the skies had cleared on October 14, 2024, the folks that were there in person and online were treated to just a beautiful, spectacular picture perfect launch of the Europa Clipper on a Falcon 9 heavy. And those things never get old to watch– to watch, to see, to listen to a launch, and it’s great to see that this launch was successful.

And we are on our way. Europa clipper is on its way to Europa.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: I imagine that watching any launch is very exciting and maybe a little bit nerve wracking. What was the energy like at NASA?

PADI BOYD: Well, it really depends on your role in the mission. Of course, anybody who has worked on this mission in any role over last decade plus is glued to that screen and is going to be watching minute by minute. There is a lot of anticipation and trepidation even but also so much excitement.

There’s so much work and preparation and testing that goes into getting a scientific payload ready for launch, and launch is one of the most challenging episodes that it’s ever going to go through. It’s just a lot of energy. A lot of things can go wrong very quickly, so there is that just pent up stress about what’s going to happen. So many people were just really glued to the either– with their eyes at Kennedy or on their screens on their computer.

If you’re not part of the mission, then you’re still really excited about it because you probably know someone who is part of the mission. Or maybe you’re just really interested in Europa because it’s a really, really interesting place in our solar system. So lots of emotions, mostly just lots of fingers crossed and then huge relief and happiness and joy.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So tell us about some of the scientific instruments that the spacecraft is carrying.

PADI BOYD: So the spacecraft has a variety of instruments. It’s actually got a huge number of instruments, nine instruments. Going to be a tenth experiment. Five of them are meant to do measurements of pictures and spectra from the surface of Europa, and the other five are meant to just tell us what are the conditions there in the Europa environment. What’s the magnetic– the radiation environment like. What about particles?

It’s really a great chance for all of these instruments to work together to really interrogate this body in our solar system. We’re going to be like nosy neighbors dropping in every couple of weeks and really taking a look around and sniff around. They’ll be able to tell us about its surface composition. What is the geology like on this body? What about that ice crust and variations from position to position and with time?

And then what’s going on at the surface under the ice crust, under that ocean that we think has a good amount of salt, but how much? We want to know that. We want to measure that.

What’s the surface like? What are the interactions of these parts like? And what about how they all interact with that very punishing radiation environment around Jupiter?

So it’s filled with instruments. It’s got massive solar arrays on it to power that whole suite of instruments, and then it will send the data down when it gets far away from Europa after those close approaches. And the scientists will sift through that every couple of weeks to get the fundamental data that they need and then also plan for what to do next on the next flyby.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Europa Clipper has all of this fancy science gear, but it also has something that surprised me, a really beautiful poem. So tell us a little bit about that.

PADI BOYD: Oh, thank you for bringing that up, because I think this is just such a beautiful part of the story. Ever since NASA started sending probes out into the solar system, they’ve taken some time to put a human imprint on it, to send something like a message in a bottle out there to talk about who sent this probe and why.

What is humanity all about? Why are we building these things on the surface of our planet Earth? What are we learning? What are we hoping to learn?

Europa Clipper follows that tradition. It has literally a message in a bottle. We’re throwing this spacecraft up into space to another waterworld from one waterworld to another, just like folks threw messages in a bottle in the oceans of the Earth. So this particular message in a bottle has so much cool stuff on it including this poem that was written by the poet laureate of the US Ada Limon, and it’s absolutely beautiful. You can hear her read it online if you’re interested in it, but it really just touches on what is the mystery that is driving humanity to put such an amazing spacecraft in orbit around Europa and to really understand the water on that world and how important water is for humanity and what we’re hoping to find in the water in Europa.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow, that’s so lovely. Padi, what’s been the most exciting part of watching this mission come together for you?

PADI BOYD: Oh, boy, that is a great question. I think it’s the context in where we’re launching today. So it takes well over a decade to plan an enormous flagship mission like Europa Clipper. In the last decade, we’ve had explosive growth in our understanding of planets around other stars. And we know now that the distribution of sizes of those planets is very similar to the distribution of, say, the moons and the smaller planets in our own solar system. There are bodies out there around other stars that are going to be a lot like Europa.

And so while we’ll be able to use Europa Clipper’s data to answer really fundamental questions about things like water and chemicals and habitability in our own solar system, it’s also going to have profound impacts on the possibility of habitable environments in the entire Milky Way galaxy, hundreds of billions of stars in their planetary systems, and then even beyond our own galaxy to other galaxies. So how common are these life-supporting conditions out there? I think it’s a huge question that’s just getting more and more exciting and important with time.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, what a lovely note to end on. Dr. Padi Boyd is an astrophysicist at NASA and co-host of the agency’s podcast Curious Universe. Padi, thanks so much for joining me.

PADI BOYD: Thank you. And go Europa Clipper.

[CHUCKLING]

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Best send off we’ve had in a while.

PADI BOYD: Awesome.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Since its start, more than 4,000 people have contributed to the Europa Clipper mission, and I’m sure they can’t wait to get their hands on the data. So here to discuss the science of Europa Clipper is Dr. Ingrid Daubar, associate professor at Brown University and Europa Clipper project staff scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, and Dr. Tracy Becker, planetary scientist at Southwest Research Institute and co-investigator on the Europa Clipper mission. Here’s Ira Flatow.

IRA FLATOW: Welcome to Science Friday.

TRACY BECKER: Hi.

INGRID DAUBAR: Thanks for having us.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Nice to have you both on the show. You both must be pretty excited about this mission I imagine.

TRACY BECKER: Oh, yeah. We’re going to find out so much more about this incredible icy ocean world, and I think there’s just going to be so much that we aren’t even asking yet that we’re going to find out. And so I’m excited for all the mysteries and all the new questions that are going to happen.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So what kind of instruments are on this mission, and what do you hope to measure?

INGRID DAUBAR: So the mission, the Europa Clipper mission, has a suite of 10 scientific investigations, and they’re all going to work together to answer a lot of questions about the habitability of Europa. They range from remote sensing instruments. We have all kinds of cameras that are going to observe in wavelengths ranging from the UV all the way to an ice penetrating radar, and, of course, lots of visible images as well.

And we also have in situ instruments that will actually sample the environment around Europa. We’re going to look at its magnetic fields. We’re going to sample any kind of dust or ice that’s being kicked off the surface or ejected. So we’re really going to investigate this moon in all of its aspects and try to figure out these questions about whether or not it actually represents a habitable environment.

IRA FLATOW: Well, what would be the signatures of a habitable environment that these instruments might pick up on Europa?

INGRID DAUBAR: Yeah, so habitability, I think it’s evolved a little bit. It’s not necessarily I think a yes or no question. It’s really going to be looking at a spectrum of are all the ingredients there that we think are necessary for life as we know it, and what does that look like, this vast liquid water ocean? What’s the salinity of it?

Is it actually heated from below? Is the material at the surface that’s radiation processed in contact with that liquid water ocean? And what does that chemistry look like? So we’re going to be able to look at a lot of the processes that are happening at the surface and try to figure out whether that represents material exchange with the subsurface and what kind of chemistry and geology are there.

TRACY BECKER: One of the exciting things about this– by looking at habitability on Europa is that even on Earth in some of the darkest, coldest, deepest spots in our Earth’s ocean where we thought was completely inhospitable to life, we’ve managed to find life. And so those processes that Dr. Daubar just mentioned talking about is there exchange– a chemical exchange allowing– introducing energy into the system the way that Earth has at the bottom of the Earth’s oceans would be a really exciting thing to find, and those would be keys to helping us understand whether or not this moon is potentially habitable.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me about how it will fly around the moon there.

INGRID DAUBAR: Sure, yeah. So this is a– it’s a flyby mission because if we were to orbit Europa, the radiation environment is just too punishing. So we’re actually orbiting Jupiter and doing multiple very close flybys of Europa. The closest one is about 15 miles from the surface, and at that point, we’ll be traveling something like 10,000 miles per hour just screaming across the surface. These flybys, there’s about 50 of them in the nominal mission, and each one will have all of the instruments trained on Europa’s surface, gathering data at the same time.

IRA FLATOW: What would make this mission successful to you? How would you both judge that? Yes, we– this has all been a success.

TRACY BECKER: That’s a great question. I very much expect that we are going to have so many new questions, and that I think in itself will be the success. I think being able to have these beautiful high-resolution images when you think about what images we were able to take in the ’90s versus what we can take now with a camera and understanding that geology, understanding the composition, really getting to some of those big questions about what kind of salt is in the ocean, are there these active plumes, are there regions of the ice that are maybe thinner than other parts so that if there is the potential for habitability, where should we go land and what should we do next with this moon. I think if we’re able to get to any of those types of questions, that would really truly define a successful mission.

INGRID DAUBAR: Yeah, yeah, I agree with Dr. Becker. Of course, we do have formal requirements that NASA headquarters expects us to achieve, so that will be the formal measure of success for the mission. But I think in terms of the science, yeah, it’s just going to be exciting no matter what. And we’re going to be able to answer a lot of questions, but we’re also going to have a lot of new questions. And for scientists, that’s hugely exciting.

IRA FLATOW: That usually is. And this is a really big spacecraft, isn’t it?

INGRID DAUBAR: It’s huge. Europa Clipper from wing to wing is about 100 feet across. It’s the biggest spacecraft that NASA has built for a planetary mission, and part of that is because we need enormous solar panels to power the spacecraft out at Jupiter. There’s not a lot of light out there.

TRACY BECKER: It’s about the size of a basketball court when the solar panels are extended.

IRA FLATOW: And so then it’s done its laps around the moon, it’s taken all the pictures and collected all the data that you want, what happens to the Clipper after that?

TRACY BECKER: Well, then we actually are going to crash it, and that’s because one of our biggest concerns is the potential of bringing any kind of microbes from Earth that may survive the intense journey and even the experience in Jupiter’s radiation. We would never want to introduce any of those microbes to Europa accidentally. So we don’t want to have the possibility of Clipper just hanging out in the Jupiter system and one day crashing into Europa because if there is life there or the potential for life, we could ultimately destroy that with our own microbes.

So we will crash the spacecraft, and the current plan is to crash it into one of Jupiter’s other moons. But there’s also the option for crashing it directly into Jupiter. So we will dispose of the spacecraft hopefully not just after the prime mission. If we’re still doing great science and all the instrumentation are working, we could still continue the mission for a few more years, but once we do see that the mission is over, we will dispose of the spacecraft.

IRA FLATOW: That’s got to be bittersweet for scientists who– you’ve been around this spacecraft so long and worked with it and all the mission possibilities.

TRACY BECKER: Yeah, I was there for the end of the Cassini spacecraft mission at JPL, where all the scientists and engineers who had worked on this mission for many decades gathered to watch the last signals of Cassini come through before Cassini crashed into Saturn for similar reasons. Cassini, we didn’t want to contaminate any other of the moons there either. And so it was very bittersweet to see that last blip of a signal data come down and then that just be it after so many decades of planning the mission, building the mission, and, of course, doing all the amazing science that we did with that mission.

INGRID DAUBAR: I study impact craters, so I’m going to have really mixed feelings because we’re also going to create a new impact crater on one of Jupiter’s other moons. And that itself is a really interesting scientific experiment.

IRA FLATOW: A geeky sort of thing you want to see. One last question before we go. I want to hear your absolute favorite Europa fact. Tracy, want to begin? Fun fact about Europa.

TRACY BECKER: Let me think about that for a second. Only one?

[LAUGHING]

So my favorite fact about Europa is actually that Europa, we know that it’s mostly water ice. We know that from looking at it in the visible and looking at it at infrared wavelengths. But in the wavelength regime that I like to use to study Europa, which is in the ultraviolet, it does not look like water, and we don’t know why. And so that’s one of the things I’m looking forward to most is studying Europa with the UV instrument and to understand why doesn’t it look like water at UV wavelengths.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that is something weird. Wow. Ingrid?

INGRID DAUBAR: I think probably my favorite fact is about just how few impact craters there are on the surface. We’re used to looking at other bodies– even in the same system, Jupiter’s other moons are– they’ve been bombarded for billions of years with asteroids and comets, and there’s craters all over them. But Europa has very few. Those that there are very interesting and they’re very weird shaped, so we look forward to studying those to understand it more.

But the lack of craters is actually really interesting, too, because it shows just how young this moon surface is. So there are active processes they have to be going on right now and can’t wait to find out what those are.

IRA FLATOW: How young is young?

INGRID DAUBAR: I think it’s maybe somewhere around 90 million years. It’s pretty young, yeah, compared to other surfaces.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today. And it’s a three– it’s going to take a few years before it gets there.

INGRID DAUBAR: About six years of cruise, yeah.

TRACY BECKER: We arrive in April of 2030.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, six– you think you can wait that long?

[CHUCKLING]

INGRID DAUBAR: We don’t have much choice.

[CHUCKLING]

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

INGRID DAUBAR: Thank you for having us.

TRACY BECKER: Thank you.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Dr. Ingrid Daubar, associate professor at Brown University and a Europa Clipper project staff scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, and Dr. Tracy Becker, planetary scientist at Southwest Research Institute and co-investigator on the Europa Clipper mission.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.