Lake Michigan Swimmers Enjoy ‘Unsettling’ Warm Water

6:04 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Juanpablo Ramirez-Franco, was originally published by WBEZ.

On a sunny, mid-September afternoon, Olu Demuren took a running start off the concrete ledge just south of Belmont Harbor and leapt into Lake Michigan for the first time.

“I was preparing myself for cold water,” Demuren said. “And this immediately felt very nice.”

The water along Chicago’s lakeshore averaged an unseasonable 71 degrees that day. The weather was picturesque too: clear blue skies and temperatures in the mid-80s. Annelise Rittberg watched their friends from the concrete ledge and said the weather felt “deeply abnormal.”

“While it’s fun to be out here, it’s also unsettling,” Rittberg said.

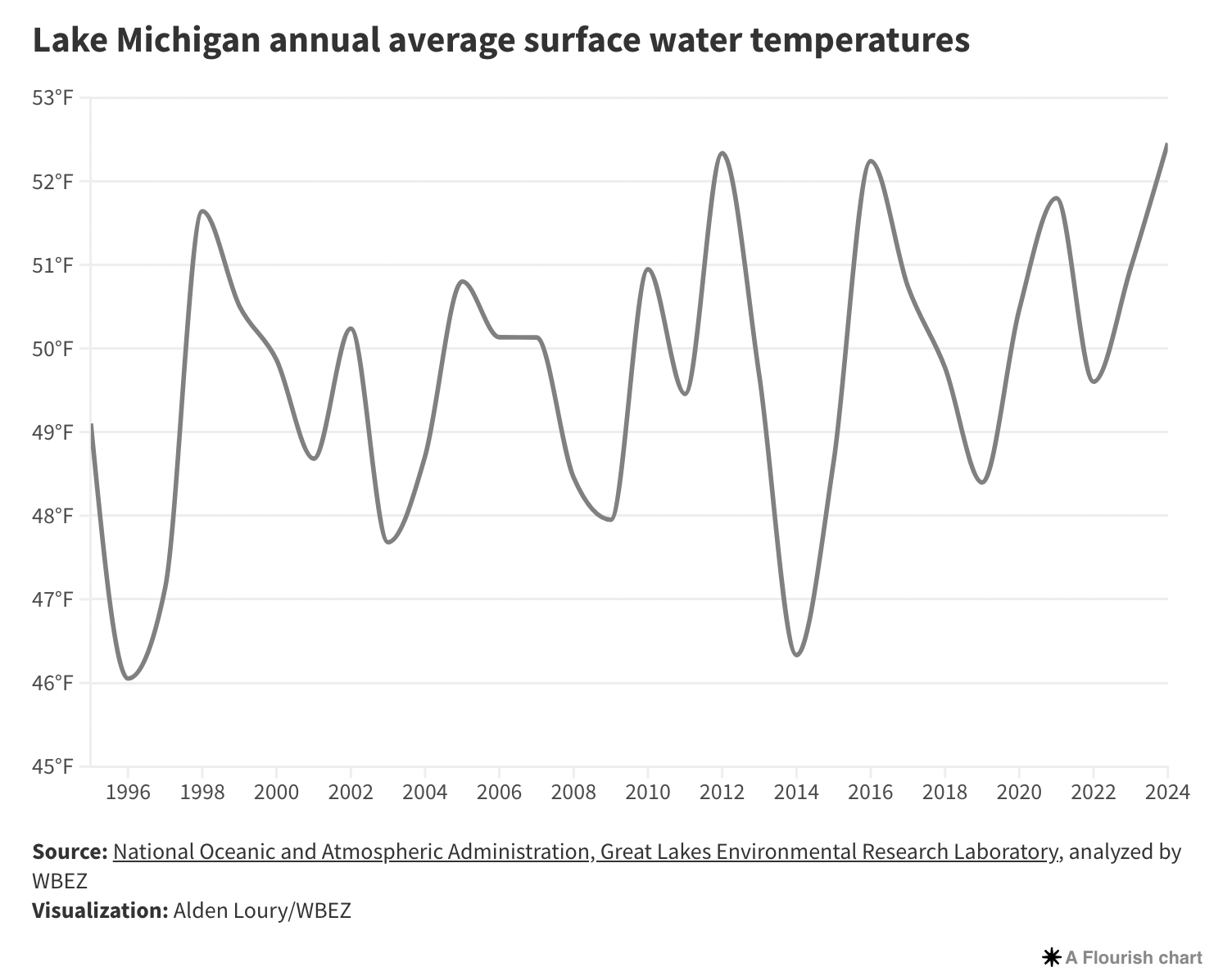

Lake Michigan is heating up. The lake’s surface temperature has surpassed the running average dating back to 1995 nearly every day this year, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) data. And it’s not just one Great Lake. All five are warming. The massive bodies of water, which provide drinking water to more than 30 million people, are among the fastest-warming lakes worldwide, according to the federal government’s Fifth National Climate Assessment.

It’s a trend that doesn’t show any sign of slowing. As heat trapping-greenhouse gasses continue to accumulate in the atmosphere, the Great Lakes region is projected to grow warmer and wetter in the years and decades to come. Over a fifth of the world’s supply of non-frozen freshwater flows through the five connected Great Lakes, forming the Earth’s largest freshwater ecosystem.

Lake Michigan started the year at around 42 degrees. That’s the hottest temperature on the first of the year since scientists started keeping track in 1995.

“On average, right now and for the past few years, we’ve been above the norm and above the trend for this satellite data record we have for temperature,” said Andrea Vanderwoude, a satellite oceanographer at NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL).

She adds that several of the warmest years on record have occurred in the past decade. This summer was warm on the whole, but by itself did not set records. However, winter temperatures did.

“Winters are in fact, getting warmer and warmer, both in the lakes and in the air and the land around us,” said Drew Gronewold, a professor of environmental sciences at the University of Michigan. “Winter is vanishing from the Great Lakes.”

Average winter temperatures in the upper Midwest are several degrees warmer today compared to 50 years ago. This is important because how heat accumulates in the lakes in one season largely determines what happens the following season.

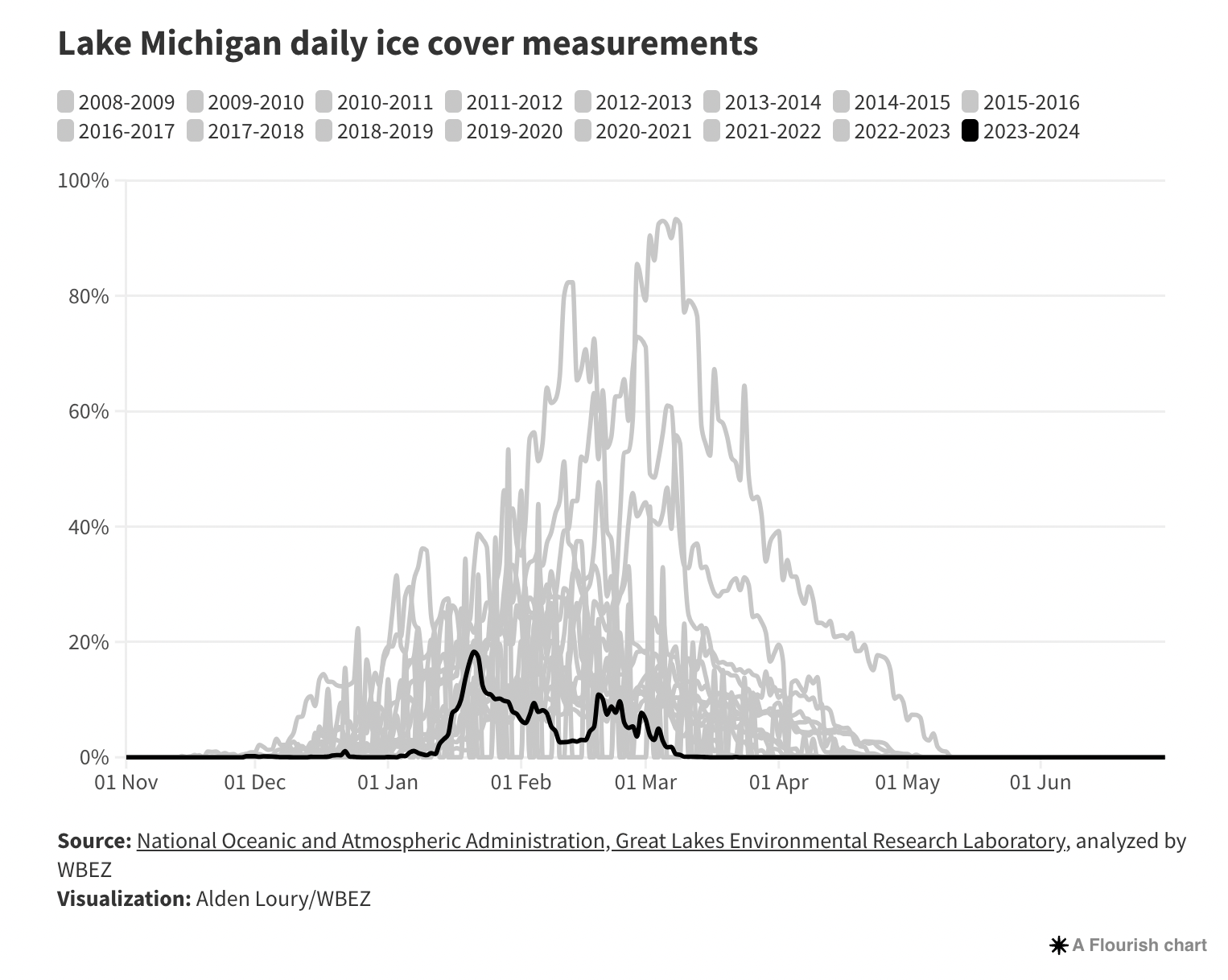

As a result, lakes that have consistently experienced seasonal ice cover since the last glacial stage are today seeing less and less of it. According to an analysis by GLERL, ice cover fell by approximately 5% per decade between 1973 and 2023. Today, there’s around 25% less ice cover than there was 50 years ago. This year has been the fourth lowest year for ice cover across the Great Lakes on record.

“This past ice year was one of the lowest ever,” said Gronewold. “Much of that time period was at record lows, and that is really a sort of the shade of things to come.”

Still, despite the warming trends, scientists said ice won’t be completely disappearing from the Great Lakes any time soon.

As Rose Sawyer dried off from her dip in the lake, she said that as far as she remembers, Lake Michigan has always varied.

“It’s weird to be swimming here this late, but it’s also just like the lake is kind of a constantly changing thing,” Sawyer said. “It’s not it’s not like a static object.”

While it’s true that Lake Michigan, like all the Great Lakes, have always shown variability from year to year, the overall trends conform with a global shift toward a warmer planet. That won’t just mean longer beach seasons on Chicago’s lakefront. It’ll mean a longer commercial shipping season, changing migratory patterns for fish and more intense storms. Here on Chicago’s lakefront, it will mean even more erosion and smaller beaches.

In the meantime, Demuren and their friends say that even if they are all out of 85 degree Chicago beach days, they’ll probably keep jumping into the lake anyway — until, eventually, it becomes intolerably cold.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Juanpablo Ramirez-Franco is an environment reporter for WBEZ in Chicago, Illinois.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA News.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNL–

SPEAKER 3: St Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. Like most things these days, the Great Lakes are getting warmer. At Lake Michigan, for example, surface temperatures have been above average almost every day this year. Producer Kathleen Davis is here with why that is important. Hi, Kathleen.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Hey, Ira. Yes, this warm weather means that beach season in Chicago now extends into October, but it also has scientists worried about what that will mean for ice cover this winter. Joining me to talk about it is my guest, Juanpablo Ramirez-Franco, climate reporter for WBEZ in Chicago and Grist. Juanpablo, welcome to Science Friday.

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: Hey there, Kathleen. Happy to be here.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So, first, set the scene for us. You came across some late-season beachgoers in Chicago recently. What did they have to say?

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: Yes, so picture this. It’s mid-September, clear blue skies, mid 80s. We’re on one of Chicago’s famous concrete beaches on the North Side, and I come upon this group of friends. They’ve just done a team cannonball into Lake Michigan. And so while they’re drying off, I asked them. I’m like, how was it in there? And here’s what they had to say.

SPEAKER 5: Delicious.

SPEAKER 6: Incredible.

SPEAKER 7: Beautiful

SPEAKER 8: Yeah, really warm.

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: And yeah, while they say they’re having a great time, there is this thing nagging at them at the back of their mind because one of the things they tell me is that the way they think about it is that this is because of climate change.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Right. So just how warm have the Great Lakes been this year?

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: When these beachgoers came out of Lake Michigan, the lake shore was close to 71 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s pretty warm for that late in the season. It’s not the hottest it’s ever been, but it’s close.

The same goes for Lake Michigan generally in 2024. It’s warm, sure, but it’s not the warmest on record. So while the heat isn’t anomalous, that’s because it’s part of a broader trend in warming across the lakes. The way one scientist put it to me was that all the warmest years recorded across the lakes, those occurred in just the past 10 years. So again, what we’re talking about here is a trend.

But I should be clear, there were points throughout 2024 that did break heat records. So Lake Michigan started 2024 at the hottest temperature ever recorded for the 1st of the year. So that was around 42 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s really cold for sure, but that’s warm for the lake at that time of the year.

There’s another point here, which is that right at the tail end of September and the very beginning of October– so just a couple days ago– Lake Superior, Michigan, and Huron all broke heat records for a couple of days.

I want to add that there’s a lot of natural variability occurring in the Great Lakes. So major climactic patterns like El Niño or a polar vortex can swing the region in either temperature direction in any given year. So it wouldn’t be totally surprising if some weather pattern caused a really cold winter in 2025. But on the whole, what we’re seeing is a warming trend across the world’s largest freshwater ecosystem.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So the Great Lakes are warming up, but how fast are they warming up?

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: Yeah to put that into perspective, the Great Lakes are among the fastest-warming lakes anywhere in the world, and that’s according to the federal government’s Fifth National Climate Assessment. That’s this big federal study that comes out every couple of years or so, and it surveys the most recent climate science to understand how climate change is impacting the country.

But when we talk about how quickly things are warming, in the upper Great Lakes– so that’s Superior, Michigan, Huron– there are estimates of warming as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050, so midcentury–

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow.

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: –and 12 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow. That is staggering. Let’s talk a little bit about ice cover. So, I mean, looking at the maps from last winter, it appears that there was little, if any, freezing of the lakes. Tell me about what the state of this ice is.

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: Yeah, there’s been seasonal ice formation on the Great Lakes since they were first formed thousands of years ago. That’s changing. Here’s Drew Gronwald. He’s a professor at the University of Michigan.

DREW GRONWALD: Winters are, in fact, getting warmer and warmer, both in the lakes and in the air and the land around us.

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: Across the lakes, we’ve been losing something like 5% of ice cover per decade since the ’70s. What that means is that there’s something like 25% less ice cover today than there was 50 years ago. And so to bring that to the present, this year has been the fourth-lowest year for ice cover across the lakes.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Are there downstream effects– no pun intended– to having less ice cover?

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: Yeah, Kathleen, there sure are. Ice during the winter actually forms this kind of protective buffer between the lake shore and stormy, choppy waters. When there’s less of that buffer, the shore is what really feels it, so there’s more erosion, which isn’t ideal for a city like Chicago that’s built on the lake shore or so many of the other cities that are built right on the Great Lakes.

Less ice will also mean a longer commercial shipping season, and it also mean big adjustments for some fish species. Entire communities of life have evolved around this freezing and thawing cycle in the lakes. This goes back thousands of years. And as that cycle responds to a warming climate, that’ll mean changes.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, we’ll keep an eye on what this winter looks like. Thank you so, so much for joining us today.

JUANPABLO RAMIREZ-FRANCO: Sure thing, Kathleen.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Juanpablo Ramirez-Franco, climate reporter for WBEZ in Chicago and Grist. I’m Kathleen Davis.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.