Scientists Find Strong Evidence For Liquid Water On Mars

12:02 minutes

Scientists discovered that there could be oceans’ worth of liquid water hidden underneath Mars’ surface. More than 3 billion years ago, Mars had lakes, rivers, and maybe even oceans on its surface. It was very different from the arid red planet we know today.

But the question remains—when Mars’ atmosphere changed, where did all that water go? This discovery could offer up new clues and possibly spur on the search for life on Mars.

Ira talks with Maggie Koerth, science writer and editorial lead for Carbon Plan, about this discovery and other science news of the week, including why the WHO declared mpox a global health emergency, the microbiome of your microwave, a green-boned dinosaur named Gnatalie, and how love is in the air for brown tarantulas.

Maggie Koerth is a science journalist and a climate editor at CNN.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, a conversation with Dr. Anthony Fauci about his new book and how parks and campgrounds are trying to make access to the great outdoors more equitable.

But first, exciting space news. New evidence suggests there could be oceans worth of liquid water hidden underneath Mars’s surface. More than 3 billion years ago, Mars had lakes and rivers and maybe even oceans on its surface. It was a very different place from the arid red planet we know today.

But the question remains, when Mars’s atmosphere changed, where did all that water go? This discovery could offer up new clues and maybe spur on the search for life on Mars. Here with this story and more science news is Maggie Koerth, science writer and editorial lead for Carbon Plan based in Minneapolis. Welcome back, Maggie. Always good to talk to you.

MAGGIE KOERTH: It’s always good to be here.

IRA FLATOW: OK, get into the water with us, so to speak.

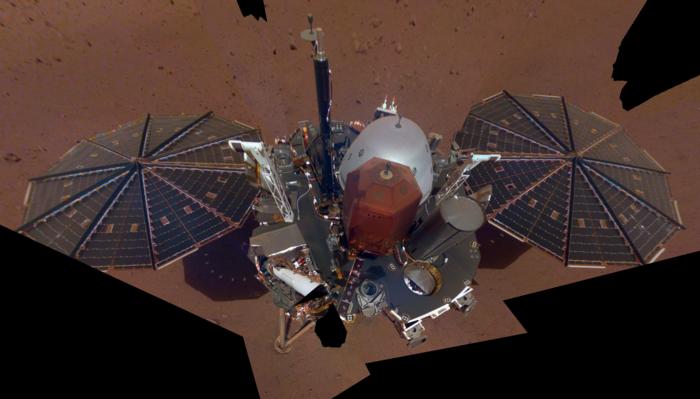

MAGGIE KOERTH: This is so interesting, because it’s data that’s coming from NASA’s Mars Insight lander. The mission for that ended back in 2022. But the data collected by that equipment is what is feeding this study now. So the lander’s job was to listen for earthquakes, and it clocked more than 1,300 of them over the course of four years.

And by documenting the speed at which seismic waves are traveling through a planet, you can tell what kinds of materials the waves are moving through. And so it’s that data from Insight that is suggesting that deep below the surface of Mars, the seismic waves are moving through liquid water.

IRA FLATOW: How deep below and how much water are we talking about?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Well, we are talking about 6 to 12 miles under the surface. This is kind of the same technique that people use to find liquid water and oil and gas on Earth. So it’s a pretty trustworthy concept. And Insight isn’t a rover. So it’s only looking right underneath of itself. But the scientists suspect that similar patches would exist all over the planet. So if they’re extrapolating from that, they estimate that there could be more water down there now than existed in those Martian oceans billions of years ago, enough to cover the whole surface of that planet to the depth of a mile.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, wow. Just to be clear, they haven’t actually found water, just signs of it, right?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, yeah. Just this seismic data that suggests that there is water down there.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, yeah. And we’re always looking for signs of water on Mars. And people think about, well, when we find it, maybe it will help space travel. But that’s a real leap, so to speak.

MAGGIE KOERTH: There’s a lot of extrapolation that’s happening from this one point. But it’s really interesting. And this is something that life depends on. So it also means that if there is life on Mars, it’s probably deep underground.

IRA FLATOW: Ooh, I like that. All right. Let’s move on to other space news. Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, also known as NIST, came up with a plan, and I love this idea, to tell time on the moon. I mean, we have to know how to tell time on the moon. We’re going there a lot. What’s the story on this?

MAGGIE KOERTH: OK, so to set this up, we have to start off with a really mind blowing fact that’s not the actual news. So bear with me. Time moves faster at higher altitudes. Literally the GPS satellites up in the atmosphere and the clocks at sea level have time moving at different rates. And that happens because of physics and the old theory of relativity. But basically, a planet’s gravity well slows down time the deeper you get into that. So again, that’s not the news. That’s just wow, news.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, it is cool news though.

MAGGIE KOERTH: But it’s something that we have to account for all the time on Earth. So then think about what happens on the moon, this object with a much lower gravitational field than Earth. And so if you want clocks on the Earth and clocks on the moon to stay in sync, you’ve got a problem. Right now, the scientists think that clocks on the moon would tick about 56 microseconds a day faster than those on earth, which isn’t much, but it matters if you’re trying to have human habitation there, have technology be synchronized between the two.

IRA FLATOW: Right. And you need it for figuring out where you’re going to land your spacecraft and things like that.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Exactly. And so that brings us back to this actual news. So NIST, what they have done is work out the math that would make it possible to synchronize time on the Earth and the moon, this extremely crucial thing to establishing any kind of human base or even just permanent technological infrastructure.

IRA FLATOW: What do we call it? Moon time?

MAGGIE KOERTH: We could. In fact, Lunar Standard Time would be a pretty good thing to call it. And the paper is, it’s mostly a math paper. So John Timmer at Ars Technica counted 55 equations in the paper itself and another 67 the appendices. So if you were really into equations, go check this paper out. It’s definitely going to satisfy.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go back to Earth and the WHO declaring mpox, the virus previously known as monkeypox, as a global emergency. What’s happening?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, so the 2022 mpox outbreak in Europe and the United states, that was a pretty mild thing. Less than 1% of the people who were infected died. And it was pretty quickly brought under control with vaccines. But there’s a very different scenario playing out in the Congo and nearby countries in Africa right now. And the situation is severe enough that you’re getting this global health emergency happening.

IRA FLATOW: So what led to this outbreak? Do we know?

MAGGIE KOERTH: We don’t know exactly what led to the outbreak, but there’s two big differences and two big problems that are happening. The first is that mpox, this one is called clade one, and it’s really different from what we experienced two years ago, which is called clade two. The clade one mpox that’s spreading in Congo now appears to have a death rate of between 3% and 4%. More than 500 people have died. Almost all of them have been children, which is another big contrast to how it was spreading two years ago.

And while that virus from two years ago was causing really noticeable lesions on hands and chests and feet, this one is kind of slipping under the radar a little bit, because the lesions are often just on the genitals and people can go unnoticed, spreading it around through close contact without anyone knowing that there’s a sick person moving around.

But one of the big problems here also is just resources. Congo and the other countries that are affected, they don’t have the vaccine access that the West did two years ago. In fact, when the US had pledged to send about 60,000 doses of vaccine to Congo and Nigeria back in April, and none of that’s arrived yet. And Congolese officials are asking for 4 million doses to actually try to contain this outbreak.

So declaring the emergency is kind of the WHO’s way of drawing attention and action from wealthy countries, basically saying if you don’t contain this now, it’s going to become a global problem. And that’s something we’re already seeing some signs of this week, because Sweden identified a case of clade one mpox in a person who had recently traveled to parts of Africa where the mpox is spreading.

IRA FLATOW: All right, let’s pivot to some less existential news, because I love this new study out that’s describing the microbiome of the beloved microwave oven.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, well, is this less existential, Ira? I don’t know.

[LAUGHTER]

I mean, the prevailing wisdom on microwaves is that they’re killing bacteria. You use the oven, it’s sterilizing itself. And that’s unfortunately not true. So researchers from the University of Valencia in Spain found whole colonies of extremophiles, those hard living bacteria that we normally associate with things like Antarctic ice and underwater thermal vents. And they’re just happily living inside your microwave oven.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because they’ve survived when everything else has been killed off. They’re self-selecting inside your oven.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Exactly. They swabbed 30 microwaves. Some of them were from home settings. Some were from industrial kitchens. Some were from research labs. And they found 101 bacterial strains that were growing in the Petri dishes. So this includes bacteria that are usually found in human skin, and it includes bacteria associated with foodborne illness.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow. Takeaway, get in there and clean your microwave.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yep, I did as soon as I read this.

[LAUGHS]

IRA FLATOW: Let’s wind down with some critter news. In first case, there’s a dinosaur with green bones. I never heard of that before.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Oh, this is so cool. So National Geographic ran a big story about a sauropod specimen that is going to be going on display at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. And this had photos of these bones, and some of the bones are green. They’re this gray green like the sea and in a couple of places this really gorgeous, almost bottle green.

What it turns out is that the scientists think it’s from minerals, from hydrothermal vents. That when these fossils were being created, they got mineralized with things that were coming out of these hydrothermal vents. And it happened to have color to it. It’s just a random luck of the draw, but it is absolutely gorgeous.

And the story is really fascinating also. We’re talking about scientists discovering the first bone sticking out of a bluff in Utah in 2007. And then just a decade of digging all of these pieces out, because this was a site where dozens of different species got swept into an almost 12 car pile up of fossils by ancient rivers. So they had to piece all of this out. And the sauropod specimen is named Natalie with a G after the swarms of bugs that were driving them crazy while they were doing all of this.

IRA FLATOW: How cool is that? Natalie with a G. Lastly, it’s almost mating season, I understand, for the large, fuzzy, maybe not so cuddly brown tarantula. Tell us about that.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, well, from August to October, these four inch wide hairy spiders are going to be crawling around in the open in eight states looking for someone to love, preferably another spider.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, hopefully. Are these dangerous to us?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Not really. The scientists say that one of the nice things about tarantulas is that they’re too big to just accidentally slip inside of your house under a door frame. So they’re unlikely to be in there. And they can bite you, but they’re more likely to just run away.

IRA FLATOW: And what states if I wanted to find them, I mean, should I be looking in?

MAGGIE KOERTH: Yeah, well, if you want to see a bunch of tarantulas getting it on, I would recommend Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana, which all have populations of these spiders. And the males are going to start coming out of the burrows that they normally spend most of their time in and traveling around. They’ll mate with up to 100 females in one season.

IRA FLATOW: Maggie, always, always a pleasure to have you.

MAGGIE KOERTH: Thank you so much. It’s always a pleasure to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Maggie Koerth, science writer and editorial lead for Carbon Plan based in Minneapolis.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.