Dinosaurs’ Secrets Might Be In Their Fossilized Poop

16:34 minutes

To gaze upon a full T. rex skeleton is to be transported back in time. Dinosaur fossils are key to understanding what these prehistoric creatures looked like, how they moved, and where they lived.

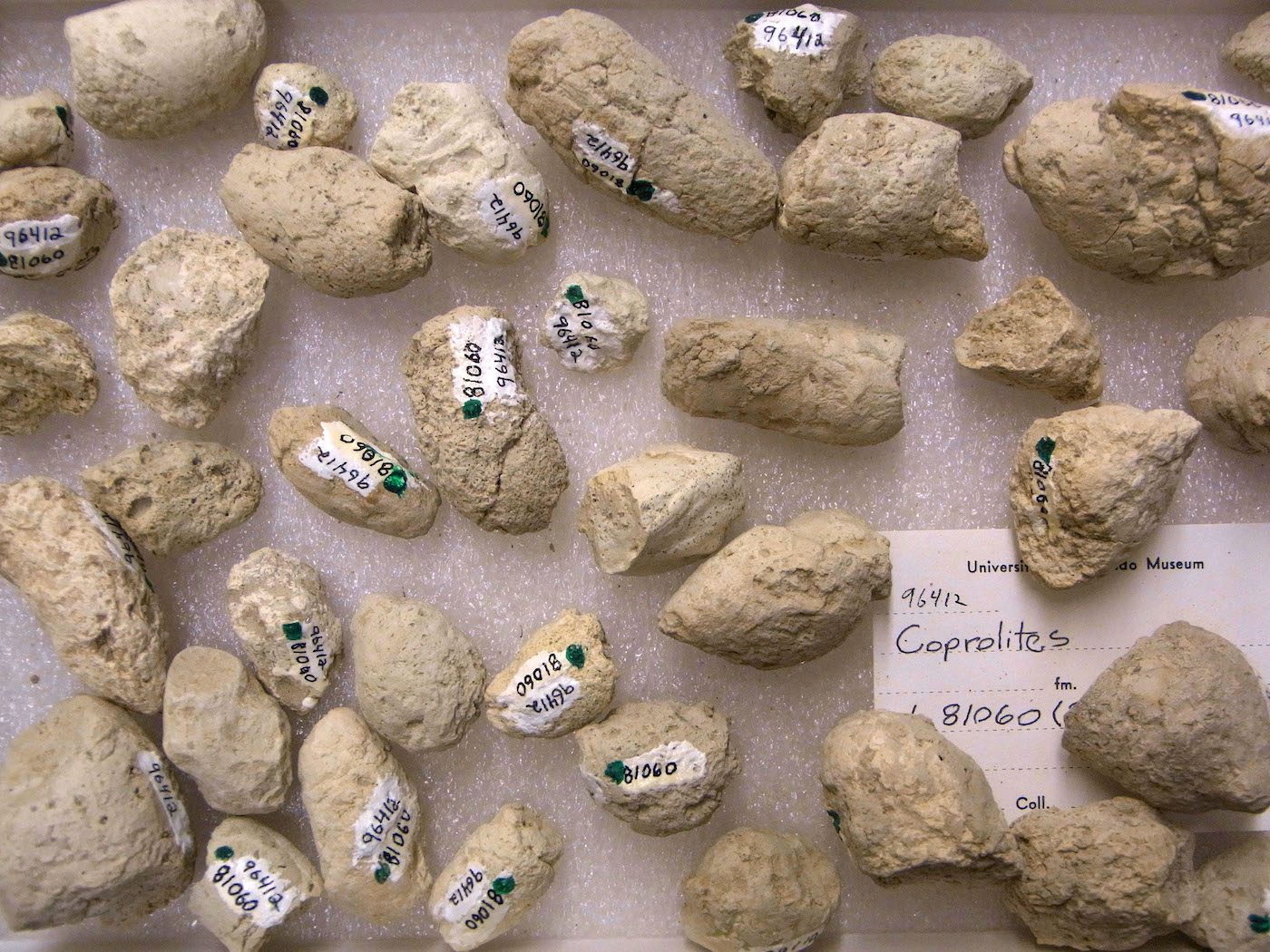

But there’s one type of dinosaur fossil that’s sometimes overlooked: poop. Its scientific name is coprolite. These fossilized feces are rarer than their boney counterparts, but they’re key to better understanding dino diets and ecosystems.

This all raises an important question: How scientists know if something is fossilized dino poop or just a rock?

At Science Friday Live in Boulder, Ira talks with Dr. Karen Chin, paleontologist and professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder to answer that question and much more.

Join us for an upcoming SciFri Event—live, in-person, and online. Be the first to hear when we’ve got something new and exciting on the calendar by subscribing to our email newsletter.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow, live from the Chautauqua Auditorium in Boulder, Colorado. Now, if you’re anything like me, whenever you go to a natural history museum, you make a beeline for the dinosaur, the dinosaur fossils. You want to see T-rex skeleton, you want to be transported back in time. And Dino fossils are how scientists understand what these prehistoric creatures look like, how they moved, how they lived, how they reproduced.

But there is one type of fossil that’s sometimes overlooked. And I’m talking about dino poop. There’s a special name for dino poop. Scientific name is coprolites, coprolites. And these fossilized feces are rarer than their bony counterparts. But you know what? Dino droppings hold the keys to better understanding dino diets and ecosystems.

But how can scientists figure out if it’s fossilized dino poop or just a rock? That’s what my next guest is going to tell us all about. Joining me to answer that burning question and a whole lot more is one of the preeminent coprolite researchers in the world, Dr. Karen Chin, paleontologist and professor of geological sciences at University of Colorado in Boulder. Welcome to Science Friday.

KAREN CHIN: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: I got to ask you, first. How does anyone get interested in this– I mean, you don’t start out being interested in dino poop, do you?

KAREN CHIN: I did not start off saying, I’m going to dedicate my life to studying poop. No. I did not. No, actually, I used to be a park service ranger, interpretive ranger. And I learned the value of when you see scat on the trail, that tells you about what’s living around you. You’re more apt to see animal sign than you are to see the actual animal.

So then when I started in paleontology and I learned that people have actually found fossilized feces, I thought that was the craziest thing. I thought it was so interesting. And I ran to my boss, Dr. Jack Horner, the proponent in Jurassic Park.

IRA FLATOW: He’s a famous guy. Yeah, very famous guy.

KAREN CHIN: I said, Jack, did you know that some people have found fossilized feces? And he said, yes. And I’ve found some, too. And that began my journey.

IRA FLATOW: And so how many fossilized feces, got to say those F words quickly together, do you think you have found in your career? How many of them? Give me a ballpark estimate.

KAREN CHIN: OK, I’m going to cheat and say, I’m going to talk about fragments, not a single pile. Hundreds.

IRA FLATOW: Hundreds of them.

KAREN CHIN: Hundreds. Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And where do you– did you find most of them?

KAREN CHIN: I found many of them in Montana, some in Utah, up in the Arctic, down in here in Colorado.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow. And OK, what– when you study them, what can they tell you about the dinos that just the other regular fossils can’t?

KAREN CHIN: Yes, I like to emphasize to people that there are two kinds of fossils, the body fossils like bone, shell, and wood, they tell you who the characters are in this drama of past life we’re trying to reconstruct. But we have to kind of assume what their actual behavior was. Trace fossils like fossil feces, fossil footprints, and fossil burrows, they tell you about activity.

And so they can actually fill in the picture of what these main major characters were doing in an ecosystem.

IRA FLATOW: Such as? What kinds of things were they doing?

KAREN CHIN: Walking around, feeding– the challenge is, is it’s sometimes difficult to link the character with the trace fossil. So in my work, I spend a lot of time acting like a detective trying to figure out who dung it.

IRA FLATOW: You really belong on this show. You really–

KAREN CHIN: Well, you have to figure out who the poopetrator was.

IRA FLATOW: Can you see other animals that come– fossils of other animals that the dino ate, perhaps? Dung beetles or something like that?

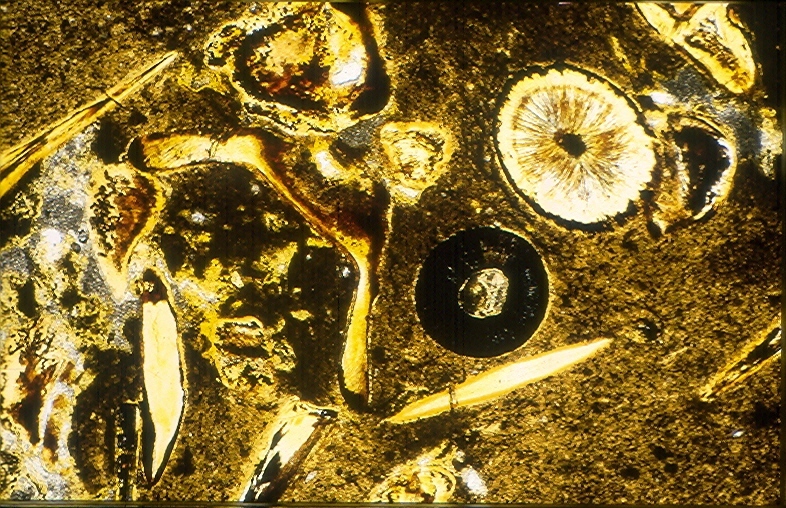

KAREN CHIN: Well, in a coprolite that may or may not be produced by a dinosaur, could be produced by fish, or mammals, you can see skeletal elements like bone, you can see shell, I’ve even found– we’ve even found fossilized muscle tissue, plant tissue. And you can also see burrows of coprophagous animals, animals that were feeding on dung, that have burrowed into that dung.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Now, you have brought some samples with you, right?

KAREN CHIN: Yes, I brought a couple samples here. I brought these here that show a very typical size and shape. This looks like dog dung, but it’s actually mineralized. Those are easy to recognize. But when you’re talking about feces from a large animal like a dinosaur, oftentimes, they break up either when they’re falling from the animal, or they’re stepped on, or just through geologic processes. This is part of a dinosaur dung piece right here. But the original size was probably on the order of about 6 or 7 liters, which is about the size of a basketball.

IRA FLATOW: And how do you know it’s dung and not a rock?

KAREN CHIN: That’s a really difficult question because there’s lots of fecal-shaped rocks around. And you have to look at a number of criteria. Actually, for dinosaurs, the shape doesn’t give you many clues. So you can look at things like the chemistry, you can also look for the evidence of chopped-up biotic material like chopped-up plants, chopped-up bone, you look at the sedimentological context, and also, you can look for evidence of coprophagous activity.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, the digging.

KAREN CHIN: The digging.

IRA FLATOW: All right. I know you have questions in the audience about dino dung. So make your way down while I ask a couple of more questions till you get there. One of the fossilized feces you showed us contains rotting wood. Yeah, I’m sorry. Why would a dinosaur be eating wood? I mean, what’s going on there?

KAREN CHIN: Yes. That was really surprising to find rotted wood. And it was rotted before they ingested it. You can see from the distribution and the structure of the cells inside that the lignin that holds all of the cellulose together in wood is actually gone. And to take away lignin like that, it requires an oxidative process, which you cannot do inside a vertebrate gut. So we know that those dinosaurs actually ingested rotted wood.

They can get sustenance out of it because when you take away the lignin, all the cellulose becomes available. But it doesn’t make sense for a dinosaur to focus on eating rotting wood because they can just walk out– well, I guess they’re not inside. But we can look outside and see lots of green plants. It’s much easier to generate cellulose through the growth of leaves than to grow trunks and then rot them.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

KAREN CHIN: So I spent a lot of time thinking about this and my hypothesis is that when the dinosaurs were reproducing, they actually required a higher source of protein to yoke their eggs. And we see this in living dinosaurs today, the birds, because many seed eaters will actually change their diet when they’re reproducing, and ingest more insects. So if you think about 25, 30-foot duckbill dinosaur that isn’t built for running after mice or something like that, how are they going to get a good source of protein when they’re reproducing? One way is to feed on rotting wood–

IRA FLATOW: There you have it.

KAREN CHIN: Where they have lots of access to crustaceans, insects, beetles, grubs, and–

IRA FLATOW: I’m getting hungry just thinking about it.

KAREN CHIN: Yeah, and we actually did find in some of this– this is a different coprolite. This is from Utah. And in those coprolites, we actually found pieces of crustacean. So we have evidence that these dinosaurs, these herbivorous dinosaurs, not only ingested rotted wood, but they also ingested crustaceans, probably like crabs.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow. Wow. I get it. OK, let’s see if we get some interesting questions right here. Yes.

AUDIENCE: Yeah, I have a– just wondering why some of them would petrify instead decompose.

KAREN CHIN: That’s a great question. I was so surprised when I learned that they actually fossilized because soft tissue readily decomposes. But if you bury the feces rapidly and the conditions are just right in terms of water, and chemical situations, and the bacteria, you can actually mineralize, lithify them, within weeks. People have done actually stick experiments where they have mineralized fossil muscle tissue. I mean, shrimp muscle tissue. And it happens within weeks.

Mineralization of coprolites can actually happen quickly. But you have to have rapid burial. So animals that live in environments where things are buried rapidly like lakes, their coprolites cannot be too rare. I mean, I should say it differently. Their coprolites may not be rare.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

KAREN CHIN: But if you’re looking for coprolites from terrestrial animals, like large herbivorous dinosaurs, those can be very rare.

IRA FLATOW: All right, let’s go to this side. Yes.

AUDIENCE: Out of all the dinosaurs that you found, which one was the most poop that you found of, like, a dinosaur? I don’t know how to phrase it.

KAREN CHIN: OK, I’ve found more poop that was probably produced by duckbill dinosaurs than any others.

AUDIENCE: OK.

IRA FLATOW: Is that because they– where they do their poop? It’s better preserved that you would find?

KAREN CHIN: The setting in which they pooped was just happened to be conducive to fossilization. Actually, herbivore coprolites from plant eaters are really rare. Because unlike carnivore diets where we have a lot of phosphorus when we eat meat, they have– they can help– the contents of the diet can help fossilize the feces. But herbivore coprolites, or herbivore diets, have very little phosphorus in them. So they require an external source of phosphorus to mineralize them.

IRA FLATOW: Terrific. OK, over here.

AUDIENCE: Thank you so much. This is kind of born of an earlier question. We were talking about decomposition. And I’m curious, do you guys ever find mycological processes? What kind of evidence do you ever see of new life sort of growing via the coprolite?

IRA FLATOW: You want to explain that question?

AUDIENCE: Like fungal growth. Do you ever see–

KAREN CHIN: Yes.

AUDIENCE: Yeah.

KAREN CHIN: We have found evidence for fungi in coprolites, for bacteria in coprolites, we have found the dung beetle burrows. So when we look at coprolites, we’re looking at whole ecosystems that demonstrate decomposition and recycling back into the environment.

IRA FLATOW: I asked you how you can tell whether it’s a rock or a fossil, and we’ve had– we’ve done a show on this with other scientists who say that, I don’t know how to put it, I’ll put it the way they said. If you lick it, they can tell the difference.

KAREN CHIN: Yeah, well, I don’t. Mostly, they’re talking about bone because just the texture sticks on your tongue. I don’t lick it.

IRA FLATOW: OK. No further words are necessary to explain that. We know that dinosaurs and birds are basically related. If you look at how birds poop, is there any relationship to how dinosaurs poop?

KAREN CHIN: Bird poop is usually very watery. And that’s because they fly. They have to shed weight as quickly as possible. Birds are flying dinosaurs, but not non-avian flying dinosaurs. So theirs do not have to be so watery. And you can look at a modern example, when you’re thinking of goose poop. Goose poop is very dense.

IRA FLATOW: We know that.

KAREN CHIN: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: We know that. What’s the biggest deposit you’ve ever found of dino poop?

KAREN CHIN: The biggest deposit that I’ve ever studied was probably about 3 feet by 9 feet. Not one dinosaur. Not one deposit. No.

IRA FLATOW: I was going all over the place with 3 feet by– not one– OK, good. I feel better for the dinosaur. Is there a question that you’re still looking to answer after all these years studying the dino poop?

KAREN CHIN: There are lots of questions, but I’d say one of the biggest questions is I really would like to know what the big brontosaurs, the sauropods, were eating, and how big their feces were. Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Those are the big herbivores.

KAREN CHIN: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And why do you want that the most? What’s there that–

KAREN CHIN: Just because that’s one of the biggest questions. What we can say, we have gut contents and feces from duckbill dinosaurs. But going back, especially into the Jurassic, those big animals, they were just so unlikely.

IRA FLATOW: Final question. I know you’ve been studying fossilized dino poop for years. Right? Has it changed the way you look at dino poop over those years? Have you– has your thinking evolved about dino poop over those years?

KAREN CHIN: Yes. When I first started studying coprolites, I was mostly interested in what they could tell us about diets. But as I have continued to study coprolites, I have realized that coprolites document energy transfer in the form of carbon transfer, carbon resources, in an ecosystem. And this is actually really a big deal because energy transfer in an ecosystem is one of the foundational characteristics of ecosystems. So to me, it’s really exciting, you can say. Predation, herbivory, recycling, coprophagy. And that means that these lowly little fossilized feces can actually give us a more holistic view of ancient ecosystems than we’ve looked at before.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today. Dr. Karen Chin, paleontologist, professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.