If You Rolled Colorado Out Into A Brownie, How Big Would It Be?

6:04 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Dan Boyce, was originally published by Colorado Public Radio.

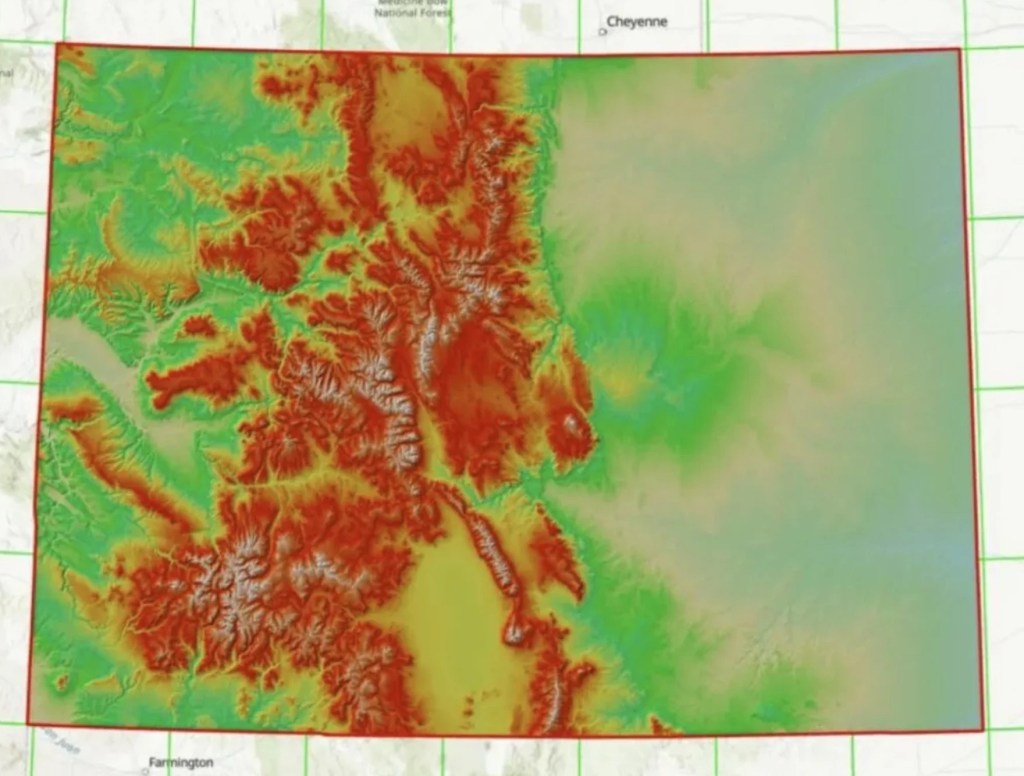

The surface area of Colorado is 104,094 square miles, according to the US Geological Survey, making it the 8th largest state in the country.

The surface area of Colorado is 104,094 square miles, according to the US Geological Survey, making it the 8th largest state in the country.

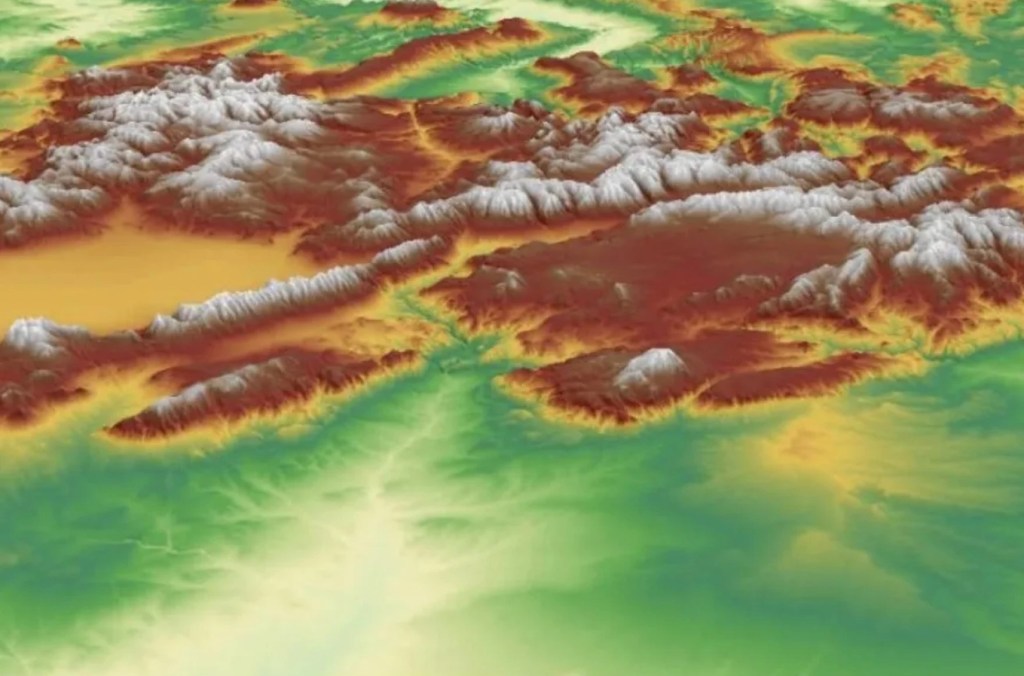

But the state, unlike our neighbors to the east, has a lot of extra geographical stuff — like mountains.

One Coloradan who loves to spend time in those big hills wondered if our dear state wasn’t getting a bit short-changed. Denver-based photographer and editor Howard Paul also happens to love baked goods. So when he posed his question to Colorado Wonders, he couldn’t help but combine his two passions.

Paul had a hunch that such a squishing would make Colorado the largest state in the lower 48. Bigger than Texas. Smaller than Alaska. (For whatever it’s worth, this numerically-challenged reporter thought that was an eminently reasonable guess.)

The first bit of due diligence was to research if this quandary had been approached before. Well, what do you know, the headline of a March 2005 article from Ski Magazine reads “How big would Colorado be if you steamrolled all of the mountains?”

The uncredited author spoke with researchers at the US Geological Survey Denver office, with the result being: “When steamrolled, the Rockies, San Juans, Sangre de Cristos, and all the other Colorado ranges would increase the state’s footprint by about 2,500 square miles — a chunk of land that’s larger than Delaware, and just a teensy bit bigger than Brunei.”

That’s not as dramatic as Paul expected. But it’s also not exactly what Paul asked. The question was not ‘How big would Colorado be if pulled flat?’ More on that distinction in a moment.

A lot has changed as far as the capabilities of the US Geological Survey in the nearly two decades since the Ski Magazine article.

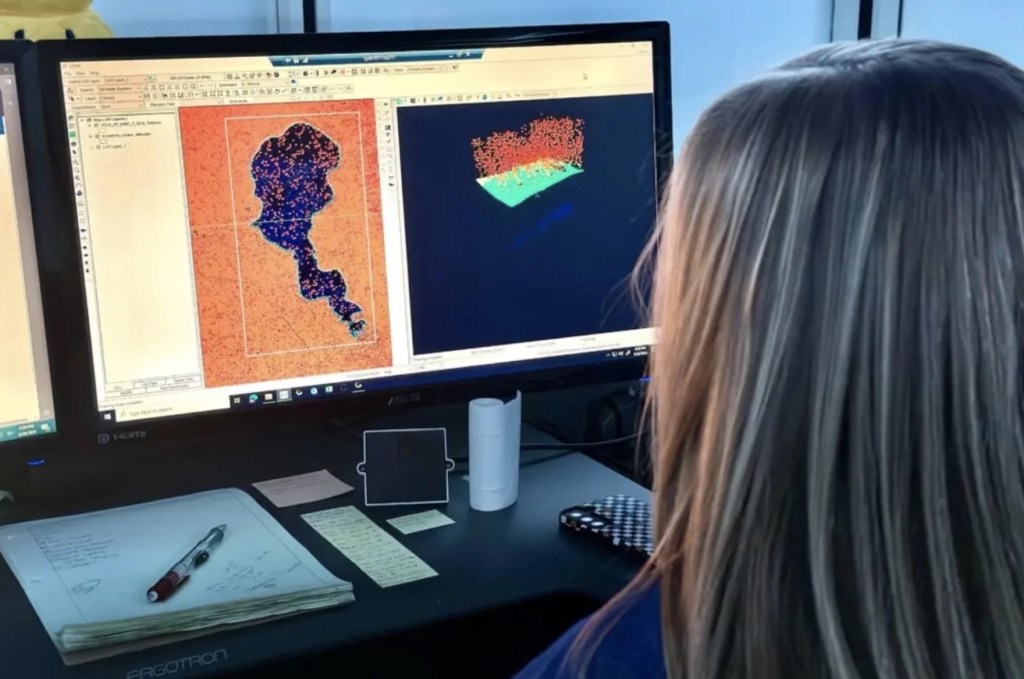

In 2016, the agency began a highly accurate aircraft-mounted LIDAR scan of the entire country. (LIDAR stands for light detection and ranging — sort of like RADAR, but with lasers.) As of today, the project has scanned about 95 percent of the United States. This enormous data set, combined with modern computational prowess, allows for a sincere tackling of Paul’s question.

Kim Mantey, director of the USGS National Geospatial Technical Operations Center, said the problem led to “enthusiastic discussion.”

“Going back to our middle school, high school math classes,” she said. “Thinking about what’s the proper formula to use?”

First, Mantey’s team had to answer some questions and set some parameters — like good scientists are wont to do.

Do we go by simple surface area or include volume?

The team considered taking the surface area of the state and stretching it out as if the uppermost layer were a scrunched-up blanket that you were flattening. (This is basically what they did for the Ski Magazine article, even more on that later.) But Paul’s question mentioned a rolling pin and a 1” thick fudge brownie. The researchers became as caught up in fanciful thoughts of bread dough and cake batter as Paul. So they decided on a true volumetric analysis, counting every bit of dirt and rock underneath the surface. The team would squish the entire state’s volume.

But down to what elevation do you squish the state?

The team discussed going to the center of the earth or going down to sea level. They settled on the state’s lowest elevation. As a previous Colorado Wonders adventure has taught us, Colorado’s lowest point is 3,315 feet above sea level, located in a normally dry flood plain of the Arikaree River.

(Let’s pause for a moment and consider something else: The Earth’s surface is far more horizontal than vertical. So much so that astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has tried to explain the planet is actually smooth, contrary to what our elementary school globes might have us believe. He says that the height of Earth’s tallest mountains on your typical school globe would be about the depth of your fingerprint.)

When we smash Colorado with our rolling pin, what is included? Land? Trees? Buildings?

They settled on just land.

The task of actually crunching the numbers fell to USGS researcher Barry Miller. And, despite all of the immense processing power needed for the exercise, he was able to craft the formula and derive the answer through the use of a pedestrian tool we all know and love to hate: an unassuming Excel spreadsheet.

To put the final answer into proper context, let’s bring in some reference standards:

The new post-squish surface area of Colorado, rolling out all of the earth from the tippy top of Mount Elbert, down through the foothills and the plains, everything down to one inch above the state’s lowest elevation, Miller came up with this result.

That’s almost 4.5 billion square miles. To look at it another way: rolling out Colorado to one inch thick leaves us with a surface area that is 22 times larger than the surface area of the planet Earth.

Howard Paul was right about one thing: Colorado would indeed be bigger than Texas.

“Astounding is an understatement,” Paul said. “It’s hard to even picture that.”

Miller was also able to guess the 2005 methodology used for the Ski Magazine article and recreated their results to explain the massive discrepancy. Again, his predecessors used the scrunched-up blanket tactic, according to him. They took just the surface layer of ground and spread it out, and they did that only for Colorado’s mountain ranges, leaving out the plains.

Does this 4.5 billion square mile figure give Colorado extra bragging rights? That’s up to you. However, let’s remember we have been comparing a squished Colorado to non-squished geographical reference points in this thought experiment. How would squished Colorado fare against a squished Texas? That remains unanswered, for now.

“I would be interested to see what it would look like comparatively for all 50 states,” Mantey said.

Until then, Paul’s reflection on the rolled-out Colorado size was poignant and on brand.

“That is one big friggin brownie,” he said.

It absolutely is.

Editor’s note: Should you desire to run the exercise yourself, the data is all publicly available. Click this link for a detailed report on the USGS methodology.

Dan Boyce is a reporter for Colorado Public Radio in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

IRA FLATOW: We are in Boulder, Colorado, this week. And while we’re here, we’re going to check in on their state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KER–

SPEAKER 2: –for WWNO.

SPEAKER 3: Saint Louis Public radio.

SPEAKER 4: KKR News.

SPEAKER 5: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local stories of national significance. Colorado has the highest average elevation of any US state, thanks to the Rocky Mountains. But think about this. What if you squished those giant mountains down, turning Colorado into, let’s say, I don’t know, a nice, ooey gooey brownie? Just how big would that brownie be?

Here to answer that very important question is Dan Boyce, reporter at Colorado Public Radio in Colorado Springs. Welcome to Science Friday.

DAN BOYCE: Hello, Ira. Great to be with you.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you, Dan. So where did this wild idea come from?

DAN BOYCE: I love it so much. We got the question from a listener, a Denver resident named Howard Paul.

HOWARD PAUL: I spend a lot of time in the outdoors, and I think about brownies and German chocolate cake, and so on. How large would Colorado be if I used a giant rolling pin and rolled it flat to one-inch thick?

IRA FLATOW: That’s really cool. Now, I would hypothesize that it would be somewhere not as big as the US. What did you think?

DAN BOYCE: I would take Howard’s idea. He was thinking that it’s probably going to be bigger than Texas, but smaller than Alaska. Sounded like a great guess to me. What do I know?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

DAN BOYCE: Bigger than Texas, smaller than Alaska– I’ll go for that. Great hypothesis.

IRA FLATOW: I would go with that. So how do you even begin to calculate how big Colorado would be as a brownie?

DAN BOYCE: Well, I’ll be clear. First off, I did absolutely zero calculations for this. My first thought is I’m going to check to see if anybody else has ever approached the question.

And it turned out that there was this short article in this 2005 edition of Ski magazine. And they asked, “how big would Colorado be if you steamrolled all the mountains?” That sounds pretty close. And the conclusion of that article, it basically said that it would increase the state’s footprint by 2500-miles, which would be a little bit bigger than Delaware. I thought that was a little anticlimactic.

But I’m trying to justify this to myself. I’m thinking, OK, that’s not exactly what Howard’s question was. It’s not exactly the same thing.

And so I went up to the US Geological Survey. They have this office in Denver. And Ira, it was so humbling. They just put a team of researchers on this.

IRA FLATOW: They didn’t think it was a crazy idea. They wanted to know. huh?

DAN BOYCE: They seemed genuinely curious about it. And they really nerded out over finding the answer. And Kim Mantey, she headed that team. She’s the Director of the USGS National Geospatial Technical Operations Center. So they’re looking at this question, Ira, and they’re saying the parameters that you set for answering something like this, that’s what makes all the difference in the world.

IRA FLATOW: You got to put your mountains, and your fields, and your buildings, and everything in there before you make your brownie.

DAN BOYCE: They actually debated that very question.

KIM MANTEY: Believe it or not, this was one of the questions we asked ourselves. Do you want bare ground, or do you want trees and buildings as a part of this exercise?

DAN BOYCE: I will say, they actually did decide not to do that. They’re going to go just from the bare ground. But that’s just one of the many parameters they had to consider.

They’re thinking, are we squishing Colorado? Are we going all the way down to sea level? Are we going to go to the core of the Earth? They’re debating that.

But they decided to go, all right, we’re going to go to Colorado’s lowest elevation. And then one of the most important parameters they needed to figure out is they found out that that 2005 Ski magazine article, the methodology that that group of USGS researchers used was they basically stretched out the surface area. So picture that you have the top most layer of Colorado, it’s like a giant scrunched up blanket. And the analysts, they took that giant scrunched up blanket and they just stretched it flat. So that’s what they did in 2005.

But Howard’s question, it was very different. He’s talking about rolling everything from the ground, but everything absolutely underneath the ground– all the dirt, all of the rock, to this minuscule size of one-inch thick. And that’s how we ended up with the answer.

IRA FLATOW: And Dan, I’m on the edge of my seat. How big is the Colorado brownie?

DAN BOYCE: Let me get you some reference points here, Ira. So Colorado’s surface area before our rolling pin squish, 104,000-square miles. Now, let’s get the final answer from USGS analyst, Barry Miller. He’s the one who crunched the final numbers.

BARRY MILLER: 4,419,041,096.31-square miles.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

DAN BOYCE: We’re talking 4.5 billion now. So to think of this another way, rolling out Colorado to one-inch thick leaves us with a surface area that is 22 times larger than the surface area of the planet Earth. Here’s how Howard Paul reacted to that.

HOWARD PAUL: What? [LAUGHS] That is one big friggin’ brownie. We’re going to have to bake it in sections.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS] So what do you do with this information now? Bragging rights? You give it to the local Chamber of Commerce, the Tourist Board?

DAN BOYCE: I think as far as bragging rights, sure– whatever, if we want. It’s important for us to recontextualize and remember that we are comparing a squished Colorado to these un-squished reference points. And so how would Colorado compare to a squished Texas? That question, it still, unfortunately, remains unanswered. But Kim Mantey, the woman who led the team at the US Geological Survey, she said her team is now really quite interested in performing the squish exercise for all 50 states.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Dan, you have provided us, I think, with one of the most unusual State of Science reports ever. So thank you very much for taking time to be with us today.

DAN BOYCE: Boy, it is my pleasure, Ira. You’re welcome.

IRA FLATOW: Dan Boyce is a reporter at Colorado Public Radio. He’s based in Colorado Springs.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.