Breaking Down The U.S. Drug Shortage Problem

There are hundreds of ongoing drug shortages in the U.S. Generic drugs, particularly injectables, are most affected.

Illustration by Molly Magnell, for Science Friday

No one knows better than Sarah Louise Butler what it means to encounter a drug shortage. Butler was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, a painful autoimmune disease, in her 20s. She describes the pain as like having a sharp pebble in your shoe all the time.

No one knows better than Sarah Louise Butler what it means to encounter a drug shortage. Butler was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, a painful autoimmune disease, in her 20s. She describes the pain as like having a sharp pebble in your shoe all the time.

Butler started taking the pill form of a drug called methotrexate, which is a common treatment for autoimmune disorders and certain types of cancer. The pill worked well for years, but after a particularly bad flare-up, she switched to the injectable form of methotrexate. And that’s where she bumped into shortages.

In 2019, Butler noticed that sometimes her local pharmacy wouldn’t have the exact dose or form of methotrexate she needed. And then the pandemic hit, throwing supply chains, hospitals, and pharmacies into a state of flux. Butler started to have difficulty getting the needles she needed to inject methotrexate. The scramble for every dose continued for about a year beyond the worst of the pandemic.

“It became a job,” she says. “I was on the phone with Walgreens … and I told the lady, I said, I’m really sorry, I don’t normally cry about my health issues. But this is breaking me.”

Finally, Butler and her doctor decided methotrexate just wasn’t worth the stress. She switched to a drug called Cimzia that’s been much easier to get and has worked well. But there’s a catch: Butler says Cimzia costs about $7,400 a month. Her insurance covers most of it, leaving her with a copay of about $75 a month, which a stipend from the manufacturer helps offset. Butler’s copay for methotrexate was about $20 a month. She says that going forward, she’ll need to consider whether Cimzia is covered by her insurance. Given the cost, she would have happily stayed on methotrexate, she says, if it had just been easier to find.

Butler is one of the millions of people impacted by generic drug shortages every year, and her experience left her with questions: Why do these drug shortages continue to happen? Why do they seem to be worse with cheaper drugs? We set out to get some answers.

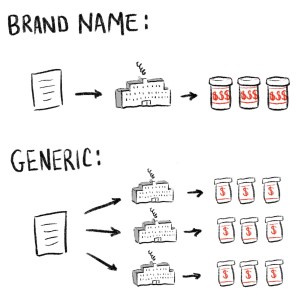

To understand the ongoing drug shortages, you need to understand the difference between brand name and generic pharmaceuticals, so let’s get into it.

When a drug is new, it’s protected by patents and exclusivity that basically mean only its original manufacturer has the right to produce it. A lot of factors go into this, but the length of a patent is currently about 20 years. These are brand name drugs, and they tend to be more expensive.

Compare that with generic drugs. Generics tend to be older drugs whose patents have expired, which means that other drug companies have the right to produce the same basic product. Generics are supposed to have the same active ingredients, dosage, effectiveness, strength, stability, and quality as the name brand drug. Generics make up about 90% of the prescriptions filled in the US.

Many of the experts interviewed for this story describe a dividing line between brand name shortages and generic shortages. Although both fall under the umbrella of the pharmaceutical industry, shortages in each are caused by unique factors, like the difference in cost.

The current shortage of Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy, for example, is driven by increased demand. Because brand name drugs are more expensive, companies stand to lose more profits when there’s a shortage than they might for a generic drug. That means there’s a greater incentive to end that shortage.

But to see why generics are susceptible to shortages to begin with, it helps to understand the larger supply chain.

The generic drug supply chain is incredibly complex. A company marketing a drug, like Pfizer, for example, isn’t always doing every step of the manufacturing.

The base ingredients used to manufacture drugs are called Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). And pharmaceutical companies either make APIs themselves or purchase them from other manufacturers. This API supply chain, and much of the drug manufacturing supply chain, is spread out across the world. Only about 30% of API manufacturing facilities that supply ingredients for drugs for the US market are themselves based in the US. The rest are spread across places like India, China, and the EU. The global nature of this network can make it difficult to conduct inspections.

Actually turning APIs into drugs is an intensive process. They get mixed with water and other buffers, and tested for stability and sterility before emerging as finished dosage forms, like a vial of methotrexate.

Those finished dosage forms then move through wholesalers and distributors. At this point, middle entities like group purchasing organizations or pharmacy benefit managers can negotiate drug prices.

And then finally, someone like Sarah Louise Butler gets her medication—or doesn’t—from a pharmacy or hospital.

Within this complex ecosystem, a category of drugs known as generic sterile injectables is particularly vulnerable to shortages. In an FDA analysis of 163 drugs in shortage from 2013 to 2017, generic sterile injectables made up roughly half of the sample.

This is, in the words of many experts, the “million dollar question,” and there are a lot of factors at play.

First, manufacturing generic injectable drugs is extremely complicated. These are drugs that are going directly into your bloodstream, so there’s very little room for error. But remember how generic drugs are supposed to be much cheaper than brand name options? That creates a bit of a paradox with generic injectables in particular: an intensive manufacturing process with very low profit margins. That can lead to quality problems in manufacturing, which is one of the main drivers of drug shortages in general.

Since generic versions of a drug are supposed to be interchangeable, low cost is the top priority for hospitals when they’re looking to buy drugs. These prices are negotiated by what you can think of as “middleman” entities in the supply chain that work between manufacturers, insurers, wholesalers and the final purchaser. As one expert put it, purchasers are sometimes paying less for a vial of a drug than a cup of coffee. And it sounds like a good thing that drugs are cheap. But it also means there’s intense low-price competition.

This creates a “race to the bottom” in terms of generic drug pricing in general. In the case of injectables, low profit margins paired with intensive manufacturing also means that getting into generic manufacturing is not easy, and one manufacturer can often dominate the market for a particular drug. So when a supply line goes down, it can have extreme ripple effects.

Another critical dimension is transparency. The generic drug supply chain sprawls across the globe and is pretty opaque. Manufacturers are required to report to the FDA when there’s a disruption that could impact supply, but the details aren’t always shared with the public and can be protected as proprietary information. Dr. Michael Ganio, senior director of pharmacy practice and quality at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, says the categories for reporting supply problems are pretty broad.

“It could just say, ‘manufacturing issue,’” Ganio says. “Does that mean that a supply line is down? Or does that mean that the entire supply line is contaminated with a fungus? Not to be alarmist, but you know, anything could fall into that category.”

This lack of transparency makes it even more challenging for purchasers to consider factors beyond cost.

Drug shortages have been going on for decades. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists has been working with a team at the University of Utah to track shortages since 2001. According to their data, drug shortages are currently at an all-time high. Clinicians interviewed for this story shared the challenges they faced during earlier periods of intense shortages, like telling cancer patients that the drugs in their treatment regimen were in short supply, and competing with other clinicians for vials.

“The way I like to think about shortages is [that] they are omnipresent. They smolder along,” says Dr. Yoram Unguru, a pediatric oncologist at The Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Now, like we’ve had other times, it’s a five alarm fire. They never go away.”

In November, the Biden administration announced that it was investing $35 million in the domestic manufacturing of generic sterile injectables. They’ve also broadened the authority of Health and Human Services in regards to drug shortages, and the agency released a white paper with potential solutions this year. The Senate Finance Committee has been focused on generic shortages and also released a white paper in January.

A common proposal is to improve manufacturing by updating production lines. But that’s not going to come for free.

“There is no free lunch,” says Dr. Marta Wosinska, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a drug shortage expert. “The reason why we have this problem is because we’re not willing to spend the money, nobody’s really willing to spend the money on resilience for our supply chains.”

Another possible solution is increasing transparency around the generic drug supply chain. Proposals include things like requiring manufacturers to disclose where they get all their drug ingredients and including location details on drug labels.

Such heightened transparency links to another important facet: finding ways to incentivize more reliable manufacturing. The HSS white paper described two conceptual programs that would score manufacturers on reliability and then use those scores to incentivize or penalize hospitals based on who they purchase their drugs from.

The FDA maintains a drug shortage database, where you can see ongoing and resolved drug shortages. You’ll also find the names of manufacturers and the reported reason behind the shortage. If you’re looking for documents, like warning letters or 483 forms, check out FDA’s electronic reading room.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists has tracked drug shortage data for over 20 years. The University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy maintains an updated list of critically acute drugs in shortage. Dr. Marta Wosinska, who was interviewed for this story, has authored numerous papers and policy proposals addressing drug shortages.

Angels for Change, an advocacy organization dedicated to stopping drug shortages, works to connect patients with essential drugs and advocates for a resilient supply chain.

Indira Khera is a freelance journalist based in Chicago.

Dr. Eli Cahan is a journalist and physician based in Boston.