Painting Wind Turbine Blades To Prevent Bird Collisions

8:21 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Will Walkey, was originally published by Wyoming Public Media.

Wind energy is expected to be a big part of the transition away from fossil fuels. But that comes with consequences, including the potential for more deadly collisions between turbines and birds and bats. One experiment underway in Wyoming is studying a potentially game-changing – and simple – solution to this problem.

In the Mountain West, large and iconic avian species – such as owls, turkey vultures and golden eagles – are consistently colliding with the human world. At the Teton Raptor Center in Wilson, Wyo., veterinarians, avian scientists and volunteers often treat birds for lead poisoning, crashes into infrastructure, gunshot wounds or other injuries.

For the center’s conservation director, Bryan Bedrosian, his work is about preserving the wildlife that makes Wyoming special.

“We should be proud of the fact that we in Wyoming have some of the best wild natural spaces and some of the best wildlife populations,” he said. I think, unfortunately, it comes with a higher degree of responsibility.”

Wyoming is a critical habitat area for many species, especially golden eagles. Tens of thousands live here year-round and the state is also a huge migration corridor between Alaska and Mexico. Unlike its cousin the bald eagle, the golden eagle population is stable at best and could potentially decline in parts of the U.S. Bedrosian said wind energy growth is a threat for a species that has always been “at the top of the food chain.”

“They’ve never had to look over their shoulder. So if they’re up soaring looking for prey, they’re never looking over their shoulder for something else to come get them,” Bedrosian. “When they don’t see that turbine blade going at 180 miles an hour, that could potentially hit them.”

Bedrosian knows that wind turbines are nowhere near the largest threat to winged wildlife. They kill an estimated hundreds of thousands of birds and bats a year, though scientific estimates vary. Still, those numbers are exponentially less than threats like power lines, cars, buildings and even house cats. But wind power is new and growing, especially in the West. The largest wind farm in the continental U.S. is being built in Wyoming, and the state has some of the best wind resources in the region.

“It’s just another piece that wasn’t there before that is affecting that kind of tipping point going towards a negative population trend,” Bedrosian said.

Additionally, since golden and bald eagles have federal protections, collisions are an expensive problem for utilities. One wind company had to pay more than $8 million in fines in 2020 after killing at least 150 eagles over a decade.

Current solutions to this issue are mixed, according to Shilo Felton, a senior scientist with the Renewable Energy Wildlife Institute. Utility companies can try stopping the turbines from spinning when birds are around, but that requires detection using complicated technology or human spotters on the landscape. Additionally, that method is inefficient.

“Curtailing turbines is generally very effective because you’ve stopped the turbine from moving. But it also results in lost energy production,” Felton said. “That lost energy has to be made up somewhere to meet our energy demands as people.”

But Felton is studying a solution that would require no technology, human intervention or turbine curtailment. One small-scale study in Norway found that painting a single blade black allowed birds to likely see the turbine better and avoid collisions. The reduction was over 70 percent, with raptors like white-tailed eagles experiencing the largest drop in fatalities.

The Renewable Energy Wildlife Institute is now working with several other partners – including the utility PacifiCorp, the U.S. Geological Survey and others – to replicate the study near Glenrock. They’ve painted 36 turbines and will use human and canine tracking to count collisions over several years. Felton says it’s an incredible opportunity to examine the statistical viability of paint as a solution.

“Wildlife conservation doesn’t happen in a vacuum. We have to consider how we as humans interact with wildlife and how we can address those challenges so that humans and wildlife can coexist,” Felton said.

This is the beginning of the research process and there are a ton of unanswered questions, like: Do North American birds see turbines the same way as European ones? Will the general public tolerate black blades? Are there energy or engineering concerns with black turbines compared to white ones?

But Jona Whitesides, a spokesperson for PacifiCorp, said it’s worth learning more because of the economic and conservation benefits it could provide for his company.

“Of course this is exciting, because it’s something new. Something that’s never really been tried,” he said. “If it is viable, it definitely could be one of those solutions that could be rolled out nationwide.”

For the Teton Raptor Center, this cooperation is encouraging. Conservation Director Bryan Bedrosian said that the growth of renewable energy is important for global bird populations trying to survive the existential threat of climate change.

“We know that our changing climate is affecting golden eagle populations on a continental scale … We have to do something about that,” he said. “That said, turbines in the wrong place are also a source of direct mortality for eagles.”

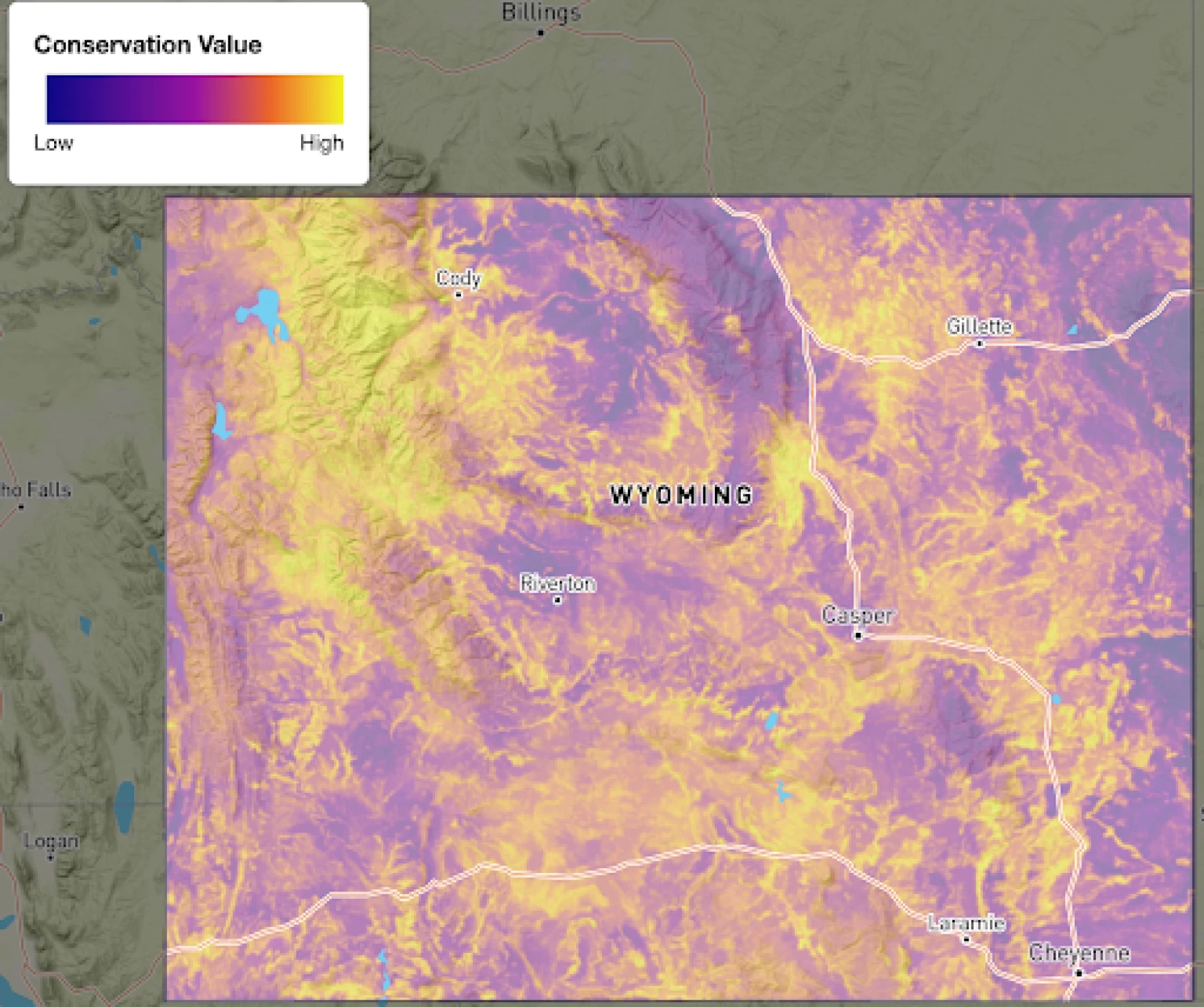

The Teton Raptor Center recently released a new tool, called RaptorMapper, to show utility companies – or other industries – where high-value breeding and migration corridors are for golden eagles in Wyoming. This could show wind developers where costly collisions are most likely, and potentially where to employ solutions or avoid building altogether.

“Wind turbines, just like every other issue, particularly with the environment, is not black and white,” Bedrosian said. “If we can reduce that risk with something as simple as painting the blade, I am all for it.”

Researchers hope to have conclusive results from this Glenrock study later this decade. They also want to compare their data with similar experiments happening around the world, including at wind farms in South Africa, Sweden and Spain.

Will Walkey is a reporter at Wyoming Public Media in Laramie, Wyoming.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow, and now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KER–

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio–

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. Wyoming is home to lots of large, iconic birds like golden eagles, raptors, and owls. Wyoming is also becoming a big state for wind energy.

And while wind turbines aren’t nearly the biggest threat to birds, there is an effort to reduce the amount of collisions between the two. And there’s an experiment going on that would be low effort and low cost– painting wind turbine blades black. The results could be dramatic. Here to tell us more about it is Will Walkey, who reported this story for Wyoming Public Radio. Welcome back to Science Friday.

SPEAKER 5: Yes, thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: So you spent some time at a bird rehab center in Wyoming, and what did they tell you about the interactions between birds and wind turbines?

SPEAKER 5: Right, so first off, I just want to say this is one of those stories that gets a lot of people talking. You know, birds and turbines have become essentially a political talking point. And that’s because turbines do indeed kill avian wildlife, as you said.

Current estimates put the number of deaths in the hundreds of thousands per year. That’s a lot. But to put it in context, the numbers are nowhere near the deaths caused by things like collisions with buildings and cars.

Even house cats kill an estimated billions– yeah, billions– of birds each year, which, yeah, that doesn’t even seem possible to me, but it’s true. So, wind turbines represent a really small threat to birds, especially compared to other dangers caused by human development and climate change. But it’s still growing and especially as we transition away from fossil fuels. So it is worthwhile to look into solutions.

I talked with Brian Bedrosian– he’s with the Teton Raptor Center in Western Wyoming– about Golden Eagles in particular, which are threatened. They’re also federally protected, which will come into play later. And they have been killed by turbines before.

BRIAN BEDROSIAN: It’s not by any stretch of the imagination the leading cause of death for Golden Eagles. It’s just another piece that wasn’t there before that is affecting that kind of tipping point going towards a negative population trend.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. So this idea of painting some of the blades of turbines black– where did that come from, and does it work.

SPEAKER 5: Right, so this idea comes out of Norway in 2020. Their researchers would paint a single blade black on turbines and compare collision data to the control group– in other words, just normal turbines with three white blades. They were looking in particular at eagle fatalities there too, and they found that painted turbines had a collision reduction of more than 70% compared to the control room.

So, huge drops in deaths there. And so lots of places are trying to replicate that study to learn more and see if it works elsewhere. Other places that are doing this include Spain, South Africa, and now Central Wyoming.

IRA FLATOW: And the idea of why it might be working?

SPEAKER 5: Yeah, that’s a good question. Of course, I can’t interview the birds and figure out myself. So there’s a couple of main theories.

One that I want to just bring up first is to talk about why, in the first place, birds aren’t seeing these turbines and are running into them. And so let’s talk about Golden Eagles in particular. The reason that researchers are theorizing that this is so fatal to them is this idea that they’re flying at ridiculous speeds, and they are miles and miles up in the air at times and scanning for prey. Their eyesight is just so absurdly good when searching for things like rabbits in a sagebrush landscape in Wyoming.

But that doesn’t mean that they’re looking in their peripheries and especially when they’re flying so fast. And researchers are theorizing that what they’re experiencing is what’s called motion smear, where things are moving so fast, these turbine blades, to the eyes of the eagle, that it all just kind of doesn’t really look like it’s real. It’s kind of like when we look at a hummingbird flapping its wings. It looks like a blur, or maybe we can’t see it at all, right?

IRA FLATOW: Right.

SPEAKER 5: So that might be what the eagle is experiencing. At least that’s what researchers are saying. And so painting a turbine blade black might kind of reduce that motion smear and make it a lot more obvious. And I’ll say, as someone who’s seen videos of these turbines being painted in Wyoming, it is quite striking when you see it. It looks really different even to the human eye than just a regular turbine blade. So I imagine it might look a little different to an eagle too.

IRA FLATOW: Even though wind turbines are not even close to the biggest threats to birds, what’s the driver for these utility companies to find a solution to reduce bird strikes?

SPEAKER 5: So of course, a lot of utilities are very interested in the conservation aspect of this, and they’ll say, hey, we’re doing this in good faith. But I do want to mention the economic angle to this. And the reality is that wind turbine blades and the deaths that they cause are very costly to wind utility companies, especially in Wyoming. One utility had to pay more than $8 million in 2020 to settle a lawsuit because they had been killing dozens of eagles across the west.

You know, this is something where a lot of birds, especially eagles, have federal protections. So if you are found liable to have killed them through collisions, you have to pay for that. And so a lot of the wind turbine companies and utilities that I’ve talked to and researched have said, hey, we’re looking to do some sort of conservation here, but we also want to reduce our economic costs and not have to kill eagles here in the process of building our farms and providing energy to the rest of the country.

And so what’s exciting about this potential solution is some of the other solutions out there include hiring spotters to look for eagles or other birds and stopping the actual blades from spinning when they see a lot of birds in the area. You can also use AI and tech and things like that to do something similar. But what that causes is it causes the blade to stop. And so that results in lost energy. The idea with painting a blade black is it can keep spinning. So I talked with Shiloh Felton– she’s with the Renewable Energy Wildlife Institute– about why this is a particularly good solution potentially for utilities around the country.

SHILOH FELTON: If it works, this potential minimization strategy of painting a single blade black would not require lost energy production in order to protect wildlife.

SPEAKER 5: And I just want to also bring up here that we are still a long way from seeing black turbine blades all over the country. You know, if this does work, we need to look into federal aviation rule changes. We need to start to understand if US as humans can tolerate looking at these black turbine blades. So we still could be years away from even getting the right data and figuring out the regulatory framework for starting to do this. But it is still really exciting, and you have to start the research somewhere.

IRA FLATOW: Are the folks at the Teton Raptor Center optimistic that this effort could protect Wyoming’s birds?

SPEAKER 5: Yeah, very optimistic. What they told me is any solution that is suitable for utilities and could actually be rolled out quickly and efficiently is one that they would support. You know, right now, Wyoming is a huge hotspot for wind energy development. In fact, the largest wind farm in the country is currently being developed and built in the southern part of the state, which is really prime golden eagle habitat and just prime habitat for great wildlife in this country in general. So they want solutions to be rolled out quickly, and they want to just make sure, most importantly, that wildlife conservation and birds and the voice of eagles are a part of this process as we transition away from fossil fuels and toward newer forms of energy like solar and wind that are cleaner but also, you know, of course do have their consequences.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, this is a really interesting story. Thanks for bringing it to us, and we’ll be following it with you, Will.

SPEAKER 5: Yes, thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Will Walkey, reporting for Wyoming Public Radio.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.