Fighting Banana Blight In A North Carolina Greenhouse

6:11 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Bradley George, was originally published by WUNC.

Bananas are the world’s most popular fruit. Americans eat nearly 27 pounds per person every year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. A deadly fungus could destroy most of the world’s crops, but a company in Research Triangle Park is trying to save the banana through gene editing.

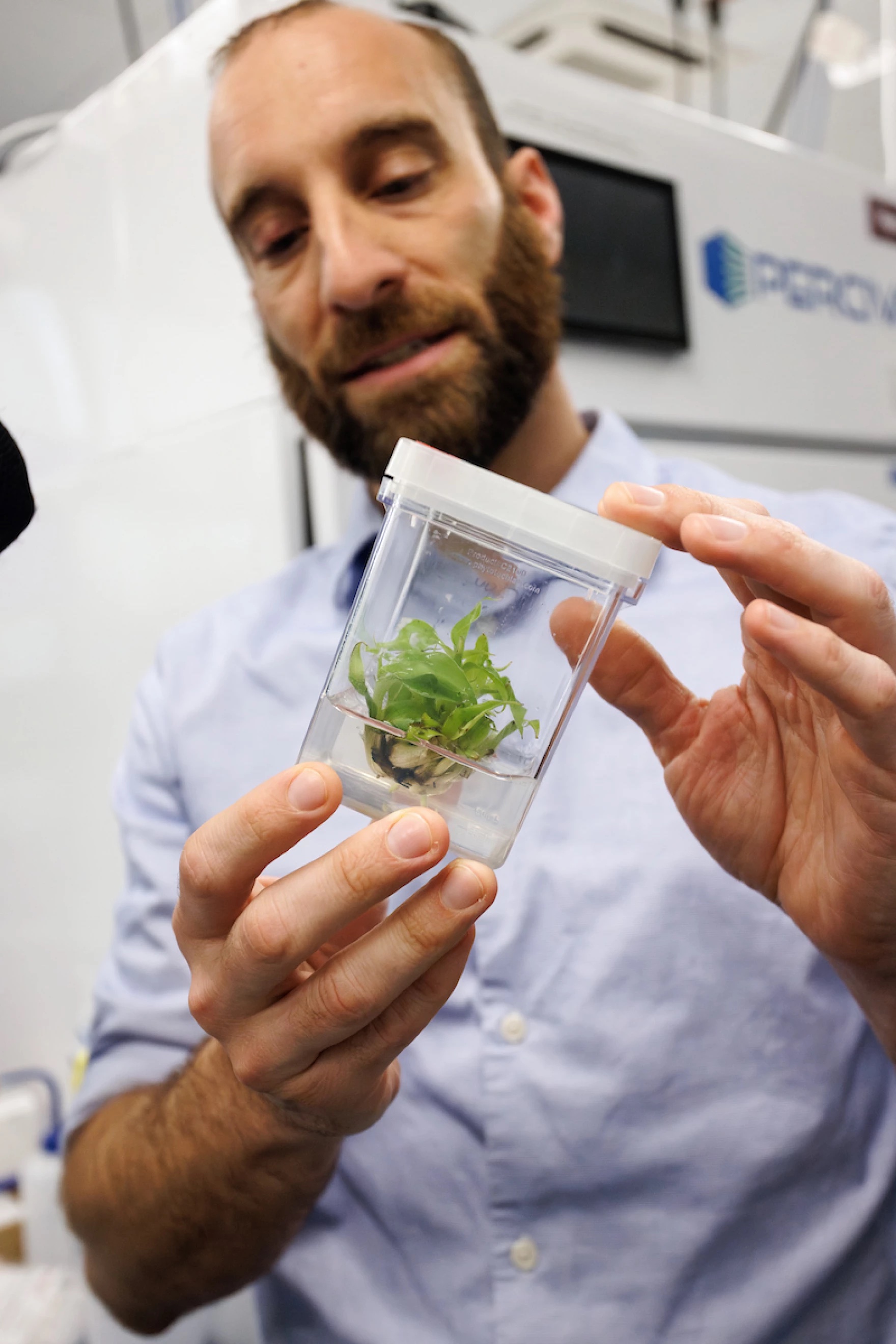

When it comes to growing bananas, RTP may not be the first place that pops in your head. But Matt DiLeo has a greenhouse full of them.

DiLeo is Vice President of Research and Development at Elo Life Systems, a biotechnology firm that’s exploring how gene editing can improve fruits and vegetables.

On a cloudy afternoon in early April, DiLeo opened the greenhouse door and stepped into a steamy atmosphere with a slightly floral odor. This greenhouse is packed floor to ceiling with banana trees. You’ve got to duck to keep the giant leaves from hitting your face. Some of the bananas are yellow, some are green, some are tiny and pink. DiLeo says they all share an important trait.

“Many of these are naturally resistant to the TR-4 fungus,” DiLeo said.

TR-4, also known as Fusarium Oxysporum, is a kind of fungus that attacks banana trees at the roots, killing the fruit. Fungicides and other chemicals can’t kill it, so farmers have few options when it invades their crop.

TR-4 was first discovered in Southeast Asia about 50 years ago. By the late 2010s, it was showing up in the soil of banana producing countries like Columbia and Costa Rica, which are home to the Cavendish banana — the variety you’ll find at your local grocery store.

DiLeo and his colleagues at Elo think they’ve found the solution to making a TR-4-resistant Cavendish banana. It’s called molecular farming — basically a form of gene editing.

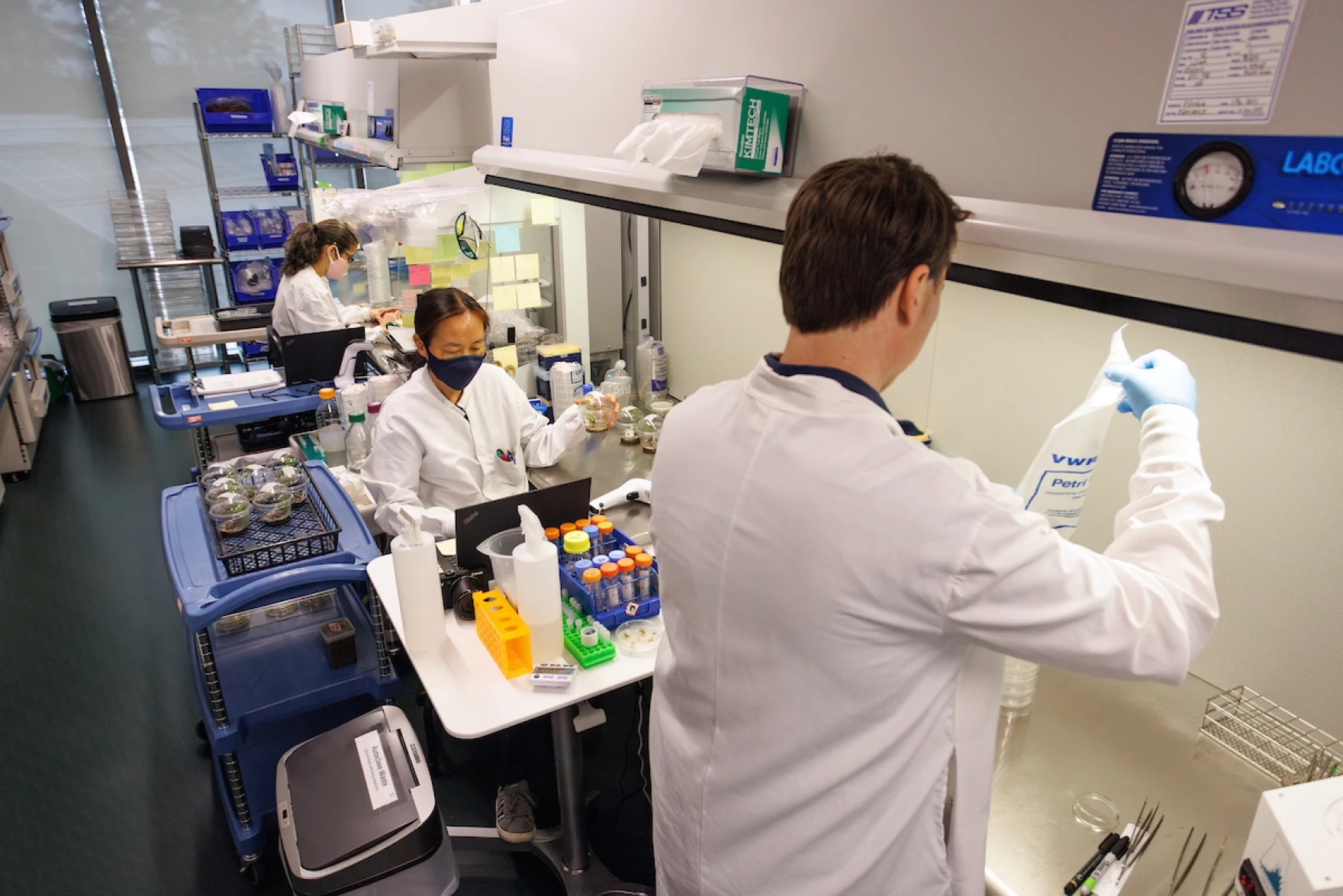

Just upstairs from the greenhouse, DiLeo walks through a maze of laboratories, where dozens of scientists are hunched over workstations and microscopes. Their task is to understand how genes affect plant traits — like how the Cavendish banana is susceptible to the TR-4 fungus.

“One of the challenges about plants is that they grow very slow, it takes a long time to work with them. And so, we look for every opportunity we can to compress timelines, so that we can make better plans in the shortest time as possible,” DiLeo said.

In this case, it’s taking genes from those bananas in the greenhouse and editing them into the DNA of the Cavendish.

“Bananas contain 30,000 different genes,” DiLeo said. “And each one of these genes helps a banana to do one thing that it needs to grow and survive in the environment. And what we do is we find those single genes that are broken, that make the banana susceptible to this disease, and we go in, and we fix that single gene.”

There are more than a thousand banana species in the world, and many — like those we met in the greenhouse — are resistant to TR-4. But they don’t produce enough fruit to feed the world’s appetite.

In 2020, Elo entered a partnership with Dole, one of the world’s largest fruit producers, to develop a banana that’s resistant to TR-4 — and just happens to look and taste like the ones consumers are used to.

In another greenhouse, a few Cavendish banana plants are spread out in a room about the size of a bedroom closed.

“These are a mix of different gene edited plants that we’ve made, we expect some to be resistant, and some won’t be resistant. And this is how we identify which ones can withstand the disease,” DiLeo said.

Dole is ready to test Elo’s bananas on farms in Honduras, but it will be a few years before they’re ready for mass production. Elo isn’t the only company wrestling with the TR-4 menace. Dole’s main rival, Chiquita, is also working on a fungus-resistant banana. Another was recently approved for human consumption by regulators in Australia.

Even the United Nations is involved.

Its Food and Agriculture Organization hosted a World Banana Forum in Rome last month to come up with a global strategy to fight TR-4. It’s not just a matter of satisfying the pallets of everyday consumers. For farmers in banana-producing nations, their very livelihoods are at stake.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Bradley George is a reporter at WUNC in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

SPEAKER: Local science stories of national significance. Want to guess what America’s most popular fruit is? Well, I’d have guessed apples, but it’s actually bananas. Yes, Americans eat, on average, 27 pounds of bananas each year. But a fungus is putting the bananas we eat in deep trouble. And scientists worry they could be wiped out. Luckily, for us, there’s a massive effort to protect our beloved bananas. And it’s happening in a state we don’t normally associate with the fruit, North Carolina.

Here to tell me about it is my guest Bradley George, reporter at WUNC in Chapel Hill. Bradley, welcome to Science Friday.

BRADLEY GEORGE: Thanks, John. Glad to be here.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So let’s talk about these bananas we’re all familiar with, the ones that our local grocery stores. What’s exactly the deal with this species?

BRADLEY GEORGE: Well, actually, there are more than 1,000 species of bananas in the world. But the one that we all know best that we see in our supermarkets and eat every day, that’s the Cavendish banana. This is one that’s grown in countries in Central and South America, like Colombia and Costa Rica, Honduras. And it became the dominant type of banana in the global markets around the 1950s, early ’60s after another species of banana, the Gros Michel was wiped out by a fungal disease of its own.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Oh, boy. So a fungus took that one out. And now there’s a fungus that’s putting this monoculture at risk too. Tell me about it.

BRADLEY GEORGE: Yeah, this is called– it has a couple of different names. The one that you’ll hear the most in biotech or banana circles is Tropical Race 4, or TR4. Now, this was first discovered in Australia in the 1990s, but it really became a concern in the last decade or so when it was found in some of these Latin American countries where the majority of the banana supply is grown. It lives in the soil. Fungicides can’t kill it. And so there are few options for growers when this spreads into their crops in terms of controlling it or killing it.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So you went to a banana research greenhouse in North Carolina to learn more about this. And maybe you can tell us what kind of research is going on there.

BRADLEY GEORGE: Yeah, this is a company called Elo Life Systems. That’s spelled E-L-O. And they’re a biotech company that’s focused on using some genetic engineering, they call it molecular farming techniques, to improve foods and deal with some of these issues that different fruits and vegetables are facing. And I spoke with Matt Dalio, who’s the VP of research and development at Elo.

And as part of my tour of their corporate campus, they have this greenhouse that’s full of banana plants of all kinds. And so one of the challenges about plants is that they grow very slow. It takes a long time to work with them. And so we look for every opportunity we can to compress timelines, so that we can make better plants in the shortest time as possible. So these bananas in this greenhouse, they’re relatives of the Cavendish.

These are bananas. Some of them are small and pink. Some of them look like the ones that we see in our supermarkets. Some of them are green. But they all have a natural resistance to TR4. And in 2020, Elo entered into a partnership with Dole, which is one of the largest banana growers to develop a TR4-resistant banana. So what Elo is doing is they’re basically– they’re looking in the family tree of bananas as it were from these other varieties and taking some of the genetic information out of them and putting them into a Cavendish banana that hopefully will be resistant to TR4.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, so you mentioned that there are all these different types of bananas, an estimated 1,000 different types. So why have we been committed so hard to these Cavendish bananas? I mean, we know there’s a risk of them being wiped out if they’re a monoculture. Why not just plant and eat some of these other types of bananas?

BRADLEY GEORGE: Well, some of these bananas just don’t yield as much fruit as the Cavendish. And the other thing is the Cavendish banana has been the dominant banana variety in global markets for so long, consumers have an expectation for how bananas look and taste, right? And farmers are accustomed to growing this variety. So that would mean different changes to them if you were to suddenly have to swap out the Cavendish with another variety.

The other issue, too, is that the banana genome it’s a small plant. But according to Matt Dalio, the VP of research at Elo, it’s a pretty complex plant to unlock the genetic structure. Bananas contain 30,000 different genes. And each one of these genes helps the banana to do one thing that it needs to to grow and survive in the environment. And what we do is we find those single genes that are broken that make the bananas susceptible to this disease. And we go in, and we fix that single gene. So they’re using these other banana varieties to find the genes that will help make the Cavendish resistant to TR4 and still maintain its dominance as the banana we all know and love.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So what’s it going to take for a TR4-resistant banana to actually be the norm to be something that we can find in our grocery stores?

BRADLEY GEORGE: Well, Elo says that they’re ready to start testing this in the field literally. They’re going to start shipping these out to the plants out to some Dole banana farms in Honduras to see how they do in the wild. But we should mention this is a global issue. It’s not just about this one company here in North Carolina. Dole’s main rival, Chiquita is also working on a resistance banana. The United Nations is involved.

Their Food and Agriculture Organization recently convened a World Banana Forum in Rome to come up with a global strategy to fight TR4 because ultimately, this isn’t just about the palates of consumers in wealthy countries like the US. It’s also about the farmers in these countries where the banana is grown in terms of maintaining their livelihood because they depend on the world’s appetite for bananas to keep their farms and crops going.

JOHN DANKOSKY: That’s so interesting. That’s all the time we have right now. I’d like to thank Bradley George, a reporter at WUNC in Chapel Hill for bringing us this story. Thanks so much, Bradley.

BRADLEY GEORGE: Yeah, thank you, John.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You can read more about Bradley’s story on our website. It’s sciencefriday.com/banana.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.