What ‘The Challenger’ Meant For Women Astronauts

In the moments before Sally Ride entered the cockpit of ‘The Challenger,’ the five other women in line for the task reflect on being pioneers.

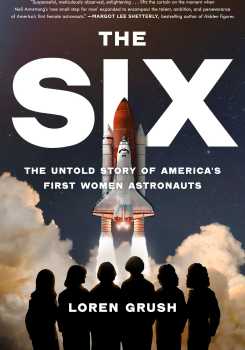

The following is an excerpt from The Six: The Untold Story of America’s First Women Astronauts by Loren Grush.

Disclaimer: When you purchase products through the Bookshop.org link on this page, Science Friday may earn a small commission which helps support our journalism.

The Six: The Untold Story of America's First Women Astronauts

Anna Fisher sat alone inside the dim cockpit of the space shuttle Challenger, the dark midnight sky painted across the cabin’s glass windows above her. The cramped room, often the setting of vibrant chatter and activity, stood still and quiet that night. The analog screens on the main control panel displayed only gray. Thousands of metallic switches, hand levers, and multicolored toggles blanketed the walls and ceiling around her—all motionless.

In the dark she gazed at the little devices intently, making sure they stayed right where they were. All the switches had been configured in just the right positions for when morning came: when the Space Shuttle would ignite its three main engines, generating more than a million pounds of thrust and rocketing a crew of five into the heavens.

Clad in a flight suit—standard issue for a NASA astronaut— Anna, a medical doctor by training, reclined on her back, stretched out in one of the cockpit’s chairs. With the Shuttle fully upright on its launchpad, she loomed high above the Central Florida coastline. The cockpit put her roughly eighteen stories up, though it was hard to tell in the dark. The only indication of the height came from the eerie light filtering in from outside. Bright xenon floodlights surrounding the launchpad bathed the spacecraft in a ghostly glow that seeped into the cockpit’s interior.

Anna may have appeared to be the cabin’s lone occupant that night, but she actually had some company. A large belly bump pushed up against her suit as she lay in the darkness. Just one month away from giving birth, Anna’s soon-to-be daughter, Kristin, was also present. The sight of a pregnant astronaut was an unusual one for the Shuttle cockpit. Anna was just the second in the corps to become pregnant in the space program’s history. For decades prior, such a thing hadn’t been possible. The astronauts had all been men.

Anna’s job was simple that evening: maintain the status quo. Earlier that day, other astronauts and flight personnel had been inside the cockpit, flipping the more than two thousand switches and buttons to their current settings. After the teams had finished their task, Anna took over to keep a watchful eye on the cabin. She was there to ensure no switch got accidentally flipped to the wrong position, a tiny error that could jeopardize the launch. Anna wouldn’t be flying in the morning, but she’d still be key to avoiding a last-minute delay or abort. It wasn’t a glamorous task, but it was crucial.

Plus, Anna loved it. After five years of sometimes grueling training, this night’s assignment was a fun one—a tiny dress rehearsal for when she’d fly on the Space Shuttle herself. She was also demonstrating her full commitment to the job, proving to any lingering doubters that her pregnancy wouldn’t get in the way of her astronaut duties. Most of all, she was doing her part to guarantee the success of the mission on deck, a flight that would become one of the most consequential missions in NASA history.

The night was June 17, 1983. The next day, fellow astronaut Sally Ride would become the first American woman to fly to space. The late-night hours transitioned to early-morning ones, and Anna eventually left the cockpit to make way for the crew. Once she departed Challenger, flight engineers began pumping more than 500,000 gallons of freezing liquid propellants into the spacecraft’s massive external tank—a bulbous burnt-orange structure strapped to the Shuttle’s underbelly. Picked for their propensity to combust when combined, the super-chilled liquids would sit inside the tank, waiting to come together and ignite, at which point the vehicle would be lofted into the sky. NASA’s giant countdown clock, located on a grassy field a few miles from the launchpad, ticked away to that exact moment.

A few more miles away, a small, curly-haired brunette stepped through the open gray metal doors of the astronaut quarters and out into the pre-dawn nighttime. Surrounded by her four male crewmates, astrophysicist Sally Ride, wearing a light blue onesie flight suit, descended the ramp out of the building, smiling and lifting her right hand to give a slight wave to a nearby crowd of photographers. Her face didn’t betray any hint of nervousness. Resolute, she walked forward with her crewmates, before turning a corner. Then, one by one, they climbed into an off-white Itasca Suncruiser RV with a horizontal brown stripe cutting across its sides. Among those accompanying the crew was George Abbey, a well-built middle-aged man with a crew cut and wearing a dark suit. George had selected Sally and her crew to fly on this mission, and he was there to see the astronauts one last time before they broke free of Earth’s gravity.

With the stars still twinkling above, the van sped down a lone concrete road to its destination: the launchpad at LC-39A. The site had been home to previous trailblazing launches. It was the same place where astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins had taken off in a monster Saturn V rocket more than a decade earlier, bound for the moon. Now, the launchpad was ready to host another pivotal mission—one that many felt was coming much too late.

The RV carrying Sally’s crew slowed to a halt. They idled just three miles from the pad, stopping right outside the famous Launch Control Center, a squat gray and white building with thick concrete walls and wide sweeping windows angled toward the sky. Since the Apollo program, the Launch Control Center had served as the central hub for monitoring all human spaceflight missions out of the Cape. It was no different today. Once more, in those early-morning hours, the facility was buzzing with energy and nervous excitement as everyone inside prepared for the mission at hand. This was where George got out of the vehicle. He wished the crew a good flight and headed toward the center. The van drove onward, LC-39A in its sights.

George took his place inside the LCC’s firing room, where hundreds of workers sat in front of gray consoles, intently watching their screens. Overhead, wide slanted windows loomed, providing a tantalizing reason to intermittently gaze outside. The glass provided a panoramic view of the launchpad in the distance—perhaps the best view one could get of a spacecraft taking off from LC-39A. The only location that might rival it was the roof of the control center. That’s where Anna would be heading shortly—to watch the Shuttle take off.

The Suncruiser finally pulled up to the pad, and Sally stepped out. She and her crewmates walked toward the giant black-and-white Space Shuttle standing triumphantly in front of them. Two towering white rocket boosters the size of skyscrapers stood attached to the massive orange tank on the Shuttle’s underside, poised to ignite at liftoff and provide the millions of pounds of thrust needed to propel the crew off the ground. With the Shuttle system fully assembled in front of her, Sally didn’t feel like she was standing before an inanimate spacecraft, but rather a monstrous breathing animal. The Shuttle’s liquid propellants periodically vented like steam from a kettle, causing the vehicle to hiss and moan as if it were alive. It took all of Sally’s will to focus on just moving forward.

The five crewmates loaded into an elevator near the Shuttle’s base and found themselves ensconced in a large metallic service structure. One of them pushed a button, starting their climb up to the 195-foot level. Reaching the top, they stepped from behind the elevator doors and trekked across a long suspended walkway jutting out into the Florida air. At the end of the corridor stood a small white room, which displayed the open hatch of the Space Shuttle cockpit. Sally and the crew gathered in the room, where a team of flight technicians were waiting for them. Sally donned a cap, her radio headset, and helmet. Then, individually, she and her fellow astronauts entered the Shuttle to be strapped into their seats for the ride ahead. Sally took her place in the seat directly behind the pilot and the commander, a spot that would give her a direct view of the control panels and the Space Shuttle’s windows during the ascent. She sat still as the closeout crew strapped her into the hard metal seat.

And then she waited, lying on her back, just as Anna had done earlier that night. With the crewmates strapped in, the closeout team left the cockpit and shut the hatch. Oh my gosh, this is really going to happen, Sally thought.

At around 6:30 a.m., the hot Florida sun peaked out from beneath the horizon, pulling high above the nearby Atlantic Ocean. The sun’s rays sizzled on the sandy beaches and swampy, gator-filled marshlands surrounding Cape Canaveral, Florida—home of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center and the Space Shuttle’s primary launch site. In the dawn light, giant throngs of people could be seen camped out with tents and folding chairs along the various shorelines of the Central Florida coast. Thousands more stood and waited along the roadways of the nearby sleepy beach town of Cocoa Beach, wearing shorts, tank tops, and visors to combat the crushing heat. A few vendors sold T-shirts while music blared from handheld radios. The song “Mustang Sally” could be heard blasting across the coast. One sign at a local bank branch read: RIDE, SALLY RIDE! AND YOU GUYS CAN TAG ALONG, TOO!

Potentially, a half-million people would be putting eyes on the Shuttle that day. And that didn’t count the possibly millions more watching on their TV sets. Many of the in-person gawkers had flown or driven hundreds of miles to make it to the edge of the United States for this launch, just to catch a tiny glimpse of history being made.

Later that morning, another astronaut stepped out into the Florida sun just a few miles from the launchpad. Shannon Lucid made her way to a quiet spot on a beach near the space center, far from the bustling crowds that didn’t have the privilege of coming onto NASA grounds. She’d been up late the night before, also working inside Challenger’s cockpit, checking all the switches that Anna had then been tasked with monitoring overnight. For this mission both Shannon and Anna were “Cape Crusaders,” the informal job title given to the astronauts who helped support the flight. Anna had been the lead Cape Crusader this round. And one of the perks of the job was getting to watch a launch alone on a relatively private beach in peaceful silence. All Shannon could hear that morning were the waves lapping the sandy shore.

She didn’t much care that she wasn’t the one sitting in Sally’s seat that morning. Just having a job—let alone one as unique and daring as an astronaut—meant the world to her. Before she’d come to NASA, she’d struggled to find employers who wouldn’t judge her for her status as both a woman and a mother. But with the space program, she’d finally found a place that would allow her to work as the individual she’d become, while putting her chemistry and science expertise to use. And as long as she got to fly, it didn’t matter who went first. Shannon waited as the countdown clock ticked away.

Standing beneath the open Florida sky, Anna looked out at the pad from the top of the Launch Control Center. The Shuttle that had been towering over her hours earlier now looked like a mere bump just along the horizon, nestled among the green treetops that spread throughout the Kennedy Space Center. A large crowd had started to form on the roof with her. A tall, lanky astronaut with bright red hair stood nearby: Sally’s husband, Steve Hawley. Next to him stood Carolyn Huntoon, a friend and mentor of Sally’s at NASA who’d taken the fledgling astronaut under her wing when she’d first been chosen to join the space program. They all chattered among themselves, swapping anxious and excited energy as they waited for the countdown to move into the final sequence.

As the seconds ticked by, more people inserted themselves into the crowd on the roof that morning. Rhea Seddon, a petite Tennessee native with light blond hair that barely brushed her shoulders, made her way to the roof’s edge. It was also her first time watching a launch on the roof of the control center. Rhea had come to see her colleague take flight, eager to be sitting where Sally was now. She didn’t know when her time would come but she was ready. A trained surgeon, Rhea had been splitting her time between emergency room work in Houston and her technical assignments at the space agency. She was also a new mom, having given birth to her son Paul less than a year earlier. She’d been the first astronaut to ever give birth, and she felt deep inside that she was ready for motherhood, her medical work, and a mission. She just needed the assignment.

It’s possible that not far from Rhea stood Judy Resnik, tan with raven hair that fell in large curls around her face. She might have looked out on the horizon at the tiny Space Shuttle, dreaming about the moment when she’d be in the same place as Sally. Or she might have been watching the launch from a television screen. Her location that day isn’t certain. But for Judy, an electrical engineer, there was no uncertainty about when her time would come. In George’s office in February she’d been assigned to her own shuttle flight, an appointment that would make her the second American woman to fly after Sally. As the seconds passed by, she knew that her own moment was on its way, even if it meant she wouldn’t be the first. To her it didn’t matter. She just wanted to fly as quickly as possible. But when she was hurtling through the sky it would mean freedom, independence, and purpose—everything she’d spent her life searching for.

While it seemed that almost everyone was at the Cape that day, one key astronaut was missing. More than two thousand miles away, Kathy Sullivan wasn’t following the launch countdown but was instead running through a checkout list for a scuba dive at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, California. An avid explorer and seafarer, Kathy had always yearned to explore the world, whether it was from the vantage of the ocean’s depths or from the towering height of the Shuttle’s position above Earth. She planned this specific dive to complete her certification for open-water scuba diving before giving a commencement address at the University of California at San Diego the next day.

For her, it was a convenient way to escape the launch. She’d hoped she might be the one chosen to be the first American woman in space. Denied that honor, she decided to accept the invitation from UC San Diego. That way she didn’t have to put on a happy face while watching the flight from Florida or Houston. It was the first Shuttle launch Kathy would miss seeing in person. She couldn’t have known at the time that her own mission was not far off—that she’d be making history in another momentous way in just over a year.

Though they weren’t all physically in the same place that day, Sally, Judy, Kathy, Anna, Rhea, and Shannon were connected in a way that would span distances and decades. They were the Six: the first six women astronauts NASA had ever chosen, after years in which the space program had only picked men to inhabit the spaceships that rocketed off Earth. Selected as mission specialists to fly on the Space Shuttle in 1978, they’d go on to become the first six American women to fly into the dark void of space, earning the unique privilege of seeing the curvature of the Earth reflected in their eyes. They’d deploy satellites and telescopes, cope with microgravity in spacesuits, maneuver robotic arms, meet presidents and royal dignitaries, speak in front of thousands of wannabe space explorers, and pave the way for dozens of women to come after.

While all earned the status of pioneers simply by being selected, one had to go first and break the country’s highest glass ceiling before the rest. Sally had been that one, achieving a feat that would make her a household name alongside the likes of Alan Shepard, John Glenn, and Neil Armstrong. Being tapped to blaze the trail before anyone else would turn her into a feminist icon, a role model, and part of a Billy Joel lyric. It would also place a burden on her shoulders that she’d carry the rest of her life.

But her assignment hadn’t been guaranteed from the start. The designation could have easily gone to Judy or Anna or any of the other women waiting in line. All were thoroughly qualified. It took a final judgment call from George Abbey and the NASA management team to seal the fates of the Six, putting Sally at the head of the pack and the others right behind her. The subsequent flight assignments would irrevocably alter the rest of their lives, leading to dreams fulfilled, historic firsts, and unimaginable tragedy.

George’s fateful nod led to Sally’s lying on her back inside the space shuttle Challenger just after 7:30 a.m. on the morning of June 18, 1983. She stared ahead, thinking about the job in front of her and how she just wanted to do it right. After three hours of reclining horizontally on the hard gray metal seat, she heard the flight controller in her ear count down to the moment that would change everything. “T-minus ten. Nine. Eight. Seven. Six. We are ‘go’ for main engine start. We have main engine start. And ignition . . .”

Adapted from The Six: The Untold Story of America’s First Women Astronauts by Loren Grush. Copyright © 2023 by Loren Grush. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Loren Grush is a space reporter at Bloomberg News. She’s based in Austin, Texas.