Chumash Tribe Champions National Marine Sanctuary

11:56 minutes

For generations, the Chumash Tribal Nation have been stewards of a vital marine ecosystem along the central coast of California, bordering St. Louis Obispo County and Santa Barbara County.

The area is home to species like blue whales, black abalone, and snowy plovers. And it’s also an important part of the Chumash tribe’s rich traditions and culture.

Tribal leaders have pushed for decades to designate the area as a national marine sanctuary. Now, the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary is in the final stages of the approval process, which would make it the first tribally nominated national marine sanctuary in the country.

John Dankosky talks with Stephen Palumbi, professor of marine sciences at Stanford University and Violet Sage Walker, chairwoman of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council, about the importance of this region and their collaborative research project.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Stephen Palumbi is a professor of Marine Sciences at Stanford University in Monterrey, California.

Violet Sage Walker is chairwoman of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council.

SPEAKER 1: For generations, the Chumash tribal nation have been stewards of a vital marine ecosystem along the central coast of California. This area, which borders San Luis Obispo County and Santa Barbara County, is home to species like blue whales, black abalone, snowy plovers, and is an important part of the tribe’s rich traditions and culture. That’s why tribal leaders have pushed for decades to designate this area as a national marine sanctuary.

Now it’s in the final stages of the approval process, which would make it the first tribally-nominated national marine sanctuary in the country. Joining me now to talk more about the importance of this region and the collaborative research they’re doing there are my guests Steven Palumbi, professor of marine sciences at Stanford University based in Monterey, California, and Violet Sage Walker, chairwoman of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council. Welcome to Science Friday.

STEPHEN PALUMBI: Wonderful to be here. Thank you.

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: Thank you for having us.

SPEAKER 1: And Violet, I’d like to start with you. And maybe you can talk about the significance of this area receiving a marine sanctuary designation. I know it’s not quite there yet, but this is pretty important, right?

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: It’s vital to our community and our culture and the coast of California that this area receives special protection. My father was the original nominator for the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary proposal. And since then has passed away and has told me to make sure that I see this campaign and designation completed because this area is, for lack of better words, just a magical place.

It’s one of a kind in the world. And with all the animals and species that you had mentioned earlier, it also is the home to the Chumash people. We have no other homeland. This is a critically important time that we protect the coast of California from all the dangers we’re experiencing with climate change, but also offshore industrialization of the coast, too.

SPEAKER 1: So– so this would protect against offshore development?

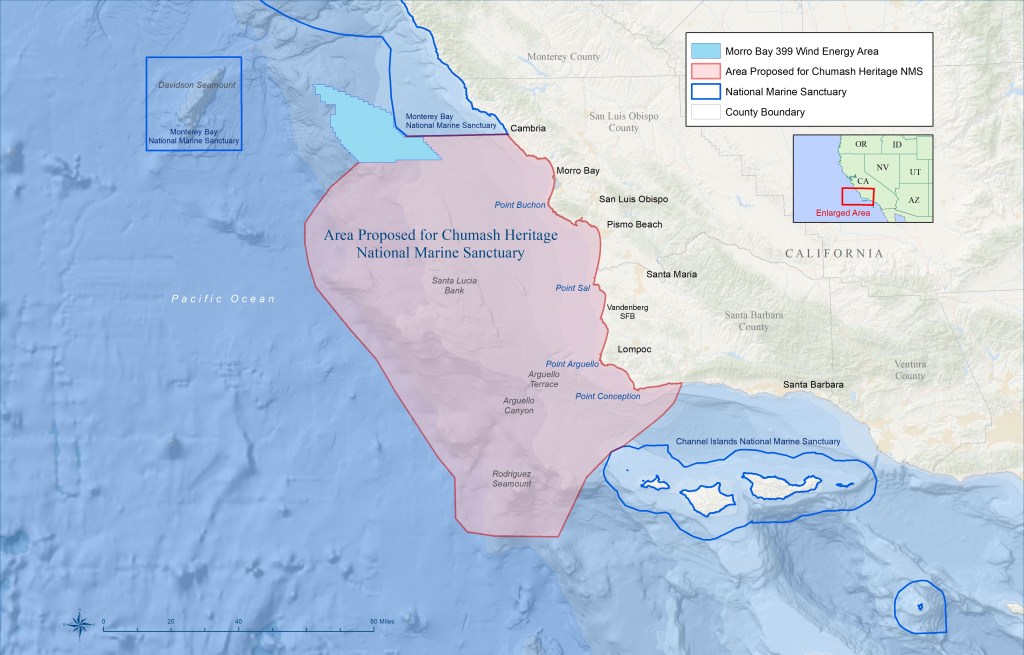

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: Most people think of offshore development as offshore oil, but this goes further. It would also protect the coastline from the intrusion of offshore wind on our coastline. So we would have this continuation of marine sanctuaries from the Channel Islands all the way up the coast of California that provide safe passage for the migratory whales and fish species like the salmon, and halibut, and tuna, the southern-protected sea otters, and all the smaller fish species that we think of like the squid, and anchovies, and sardines. And so we would create this– essentially, this corridor of protection, keeping all industrialization off of the coastline and out potentially 35 miles offshore.

SPEAKER 1: So– so Steve, as a marine biologist, this is obviously important to you as well. Violet was talking about this corridor that would be created going from one designated area to another. What else is so special about this area?

STEPHEN PALUMBI: Well, it’s an incredibly diverse area. Marine life just abounds in it. One of my colleagues here at the Hopkins Marine Station, Barbara Black, has called this the Blue Serengeti, where– where there’s just migrating huge animals, the whales and huge tunas, but also an incredible diversity of fish, part of which are in fisheries, but also part of which is in the kelp forest, which just kind of goes along the coast. And that is one of the longest forests in North America. It stretches all the way from Canada down into Mexico along the coast. It has thousands of species in it that are a vibrant part of that ecosystem.

SPEAKER 1: Yeah, and we’re talking about a huge area here. It’s about 7,000 miles?

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: Yeah, it’s 7,000 square miles. I think of it as six times the size of Yosemite or 156 miles of coastline.

SPEAKER 1: Wow. So Steve, one of the things you’re working on with the tribe is to collect eDNA or environmental DNA in the region. Can you, first of all, start off by just telling us what exactly is eDNA?

STEPHEN PALUMBI: Yeah, exactly. What is that? Well, in a lot of places, marine life, lakes, oceans, forests, soil, organisms kind of leave little bits and pieces of themselves behind. In our case, it’s scales. It’s little legs from crustaceans, stuff from snails. It floats around in the little bits in water, and it carries the DNA of those organisms in it, those little pieces. So you can collect that, filter out those little pieces, extract the DNA, sequence them, and then you can get a reading for the species that were there.

SPEAKER 1: So– so it helps you understand the diversity of the species in this area?

STEPHEN PALUMBI: It helps you see that diversity, which is really important, because there’s thousands of species. And we’re talking, like Violet said, across an incredible area. So the ability to monitor it, and look at it, and track it over time, particularly in the face of climate change, is one of the important aspects of the research that the Chumash community and we are putting together.

SPEAKER 1: I’d like to talk more about the collaboration, Violet. How– how did Steve and his team build trust with you and the rest of your community to successfully work together on this huge research project?

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: Well, that’s a great question because that is the key to a successful relationship with the tribes. And what Steve did is he just– he just kept showing up. At first, we were like, what is eDNA? And who is Steve? And then he just kept showing up, and calling us, and emailing us, and writing to us.

And I’ll tell you what tipped the scale was when I was invited to go to Our Ocean Conference in Palau. The local people there, they knew Steve, and they spoke highly of him. And I’m like, OK, well, we’re going to reach out to Steve. And it ended up, we just basically adopted him into our community. And it’s worked out really well. The best vouching for his character and what we could do together happened was with other Indigenous people first.

SPEAKER 1: Huh. So– so Steve, what has this experience with the tribe been like for you?

STEPHEN PALUMBI: Oh, it’s just been amazing. And I really appreciate those words from Violet. And the flip side has been that I did kind of call, and text, and show up, and be there, and listen, and kind of be present. And this group of amazing people just slowly just folded me in, and it was so lovely.

And then we got to talk. And when we realized that we had different things to talk about, but we could actually talk back and forth about things that we all cared about. It’s not going to be agenda-driven. It’s going to be conversation-driven. And that was just a great way to begin this talking about things that the science that we do can explain and the things that the traditional ecological knowledge that the tribe has can come together with.

SPEAKER 1: Yeah, and you’ve relied on that historical knowledge from tribal members, right?

STEPHEN PALUMBI: We have relied on it, and we have talked about it, and we’ve explored it in ways that really just open up this vistas of really interesting, I don’t know, nerdy little biology facts sometimes. And then– and then in these broad things of like, oh, yes, there’s this understanding of the oceanography and the wind patterns of that whole coastline.

SPEAKER 1: Yeah, and there’s some specific examples, too, some various species that you’ve been able to locate with help from tribal members.

STEPHEN PALUMBI: One of our first set of samples, we had a combination of species. We had sardines in this sample. We also had pelicans in this sample because the pelicans dive in and out of the water all the time. We had sea lions in the sample.

And then we had a whole set of little tiny things that are the basic food of the ecosystem. And we can kind of bring those to the tribal members, and we can talk about how do you see this? And one of those was grunion. And so we’ve been having this great conversation about the grunion, little silvery fish that spawns in the intertidal and the beach, and just talk back and forth about, well, how does this fit into your knowledge and your culture? And where do we find it?

SPEAKER 1: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. And community members, Violet, have been research assistants, and they’ve been helping to collect samples, too.

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: That’s right. That’s been one of the fun parts of this project is we’ve been training some of our younger community members and tribal members how to do the sampling. And we’ve even taken that to the next step, and we’ve decided to make traditional watercraft that is outfitted and rigged to do the sampling.

So if you imagine a very ancient way of traveling like with the hokule’a or some of these ancient voyaging canoes set up to do modern scientific research and sampling. It’s gotten some of the young people really interested in what we’re doing.

SPEAKER 1: That’s one of the coolest parts about this whole thing is using some of these traditional vessels. And in part, Violet, and it’s not just for getting the young people to learn, but they can sometimes go places that bigger research vessels can’t.

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: This is one of the pitches that I’ve been made to this project is that we can use these traditional watercraft to sample in places that we’re not going to be disturbing the wildlife. Inside kelp beds, we’re reducing carbon emissions. We’re also reducing the cost of doing the research and sampling because hiring a vessel, and chartering vessels, and having an entire team go out is sometimes cost-prohibitive. So using the traditional watercraft and using Indigenous people to do the sampling allows us to do more sampling at a lower cost.

SPEAKER 1: Before we run out of time, I’d like to ask you both if you feel as though this can be a model that can be used elsewhere. Steve, I know that you’ve done this sort of work elsewhere in the world. Do you think that there are other spots in the US where tribal communities can work with university researchers in this way?

STEPHEN PALUMBI: Absolutely, and that’s one of the really exciting and fun things about this. This new sanctuary is kind of sandwiched between two other sanctuaries that have been there for a while. And the idea that this collaboration with the Chumash can result in new techniques, streamlined efforts, more cost-effective efforts that can be done in a bigger spatial fashion, that knowledge and development can come from the Chumash community and us and then spread to the other sanctuaries is really fun to think about.

SPEAKER 1: Yeah, tell me what you’re thinking about this, Violet.

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: Well, I’d like to think of this as a pilot program for what we could help with around the world. And we call all the other marine sanctuaries and marine-protected areas sister sanctuaries around the world. So I’d like to think of this as a pilot to show what can be done and also to show how to incorporate Indigenous communities into meaningful aspects of the blue economy by providing them with training, and jobs, and meaningful engagement with research and science.

SPEAKER 1: Is there anything that you really hope to learn in the future through this project?

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: Well, I really think that this is an opportunity for the Chumash people to highlight our culture and our heritage. We can help reverse and help identify the most drastic effects of climate change on the coast here. And so I’d really like our people to be at the forefront of new discoveries and solutions for addressing our climate problems.

SPEAKER 1: Violet Sage Walker is chairwoman of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council. And Stephen Palumbi is a professor of marine sciences at Stanford University based in Monterey, California. I’d like to thank you both for sharing the story with us. And best of luck on this federal designation.

VIOLET SAGE WALKER: Thank you.

STEPHEN PALUMBI: Fabulous to be here. Thank you very much.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.