An Ambitious Plan To Build Back Louisiana’s Coast

5:04 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Halle Parker, was originally published by WWNO New Orleans Public Radio.

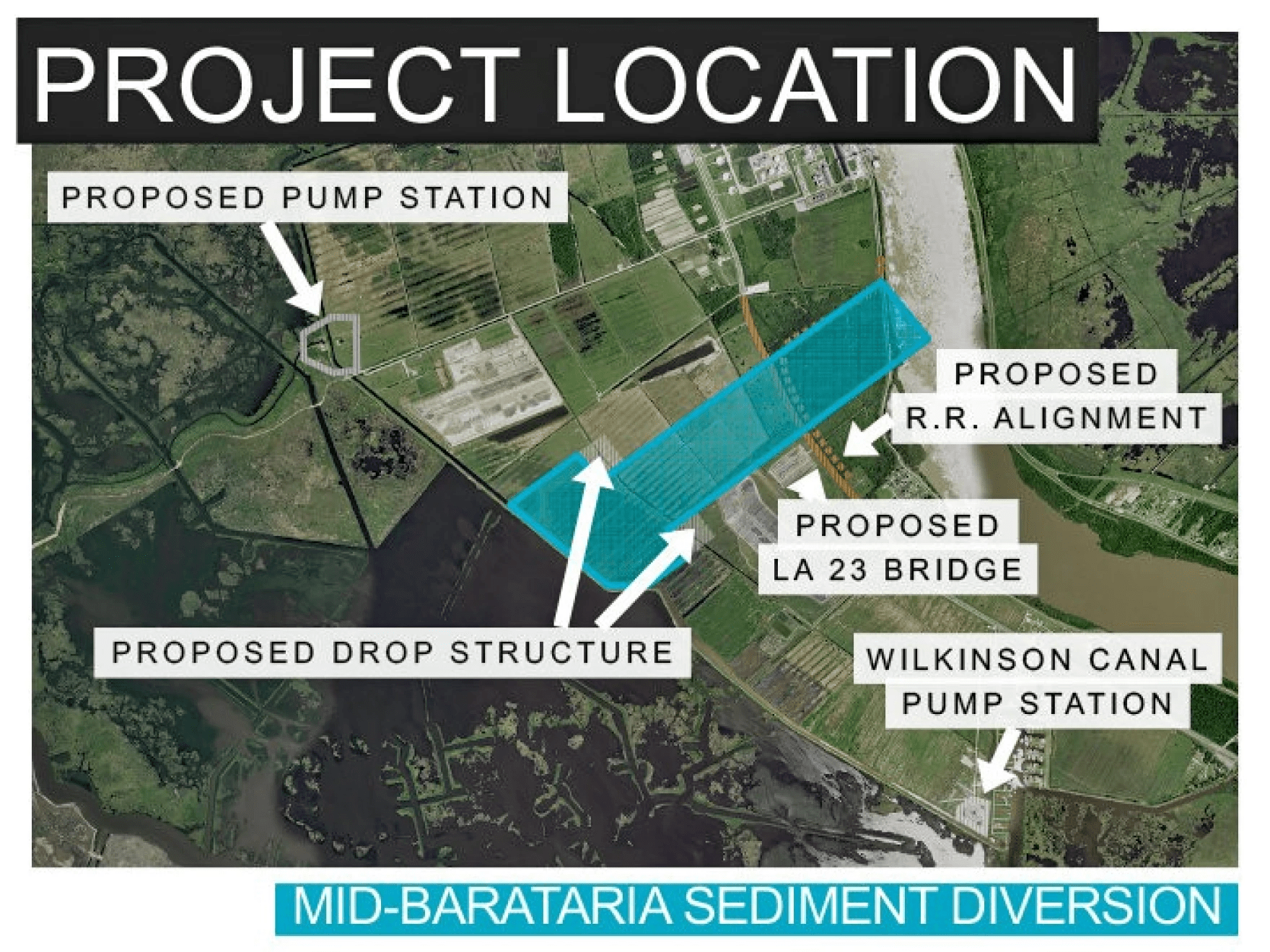

Louisiana will receive more than $2 billion to pay for an ambitious, first-of-its-kind plan to reconnect the Mississippi River to the degraded marshes on Plaquemines Parish’s west bank.

A collective of federal and state agencies—the Louisiana Trustees Implementation Group—signed off on the multibillion-dollar Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion on Wednesday. The funding will come out of settlement dollars resulting from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Once constructed, the two-mile-long sediment diversion is expected to build up to 27 square miles of new land by 2050. In the next 50 years, as Louisiana’s coast continues to sink and global sea levels rise, the diversion is also projected to sustain one-fifth of the remaining land.

“The Trustees believe that a sediment diversion is the only way to achieve a self-sustaining marsh ecosystem in the Barataria Basin,” wrote the implementation group in its decision.

With the group’s approval, Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority chairman Chip Kline said the state can move forward with bringing the project to life. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers granted the project its final permits in December following several years of environmental impact review.

“Today’s decision is the culmination of exemplary collaboration across federal and state agencies to address a complex issue with an impactful solution,” Kline said. “Coastal Louisiana is home to natural resources, communities and assets that our country simply cannot afford to lose, and this decision acknowledges its significance on a national scale and from every point of view.”

But the land-building and restoration won’t come without tradeoffs. The influx of fresh Mississippi River water could stoke flooding in communities located outside the parish’s levee system. It will also immediately disrupt the area’s seafood fisheries, which residents depend on for work. Local shrimpers and oyster harvesters have long resisted the diversion’s construction.

Studies have also suggested that the fresh water will also lead to the extinction of dolphins that have moved into Barataria Bay—a species that was harmed by the 2010 spill—as land loss has made the basin saltier.

In its decision, the trustee implementation group acknowledged that the project will have consequences.

“Reconnecting the river to the basin to restore an estuary that has been degrading and becoming more saline for almost a century would produce significant changes to current conditions in the Barataria Basin, which will adversely affect some of the species that currently reside in the basin,” the group said.

In turn, $378 million of the funding will go toward a range of programs to help lessen the project’s impacts:

Following Wednesday’s announcement, Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority officials said the state is coordinating with the Army Corps to finalize all steps needed to start construction later this year. The sediment diversion will take at least five years to complete.

Join us for an upcoming SciFri Event—live, in-person, and online. Be the first to hear when we’ve got something new and exciting on the calendar by subscribing to our email newsletter.

Halle Parker is a Coastal Desk Reporter for WWNO in New Orleans, Louisiana.

IRA FLATOW: Now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

RADIO ANNOUNCER: This is KERA.

RADIO ANNOUNCER: For WWNO.

RADIO ANNOUNCER: St. Louis Public Radio News–

RADIO ANNOUNCER: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance.

Over the decades we have been following the massive changes happening to Louisiana’s coast, especially in the southeast, where the Mississippi River ends. Climate change and levee systems have disconnected the river from coastal marshes, changing the ecosystem. Louisiana has now secured $2.2 billion for an ambitious plan to reconnect these waterways through sediment diversion.

What is that? What can we expect of it? Joining me now to talk us through this plan is Halle Parker, environment reporter for the coastal desk at WWNO, in New Orleans. Welcome to Science Friday.

HALLE PARKER: Thanks for having me on.

IRA FLATOW: Where is this money all coming from?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah. So if you remember back in 2010, there was a gigantic oil spill, the Deepwater Horizon, or BP oil spill. And so, from that settlement, that’s where all of this gigantic sum of money is coming from to pay for this project.

IRA FLATOW: Aha. Yeah. Who could forget that oil spill? Let’s talk through this sediment diversion plan. What is that? What does it really mean?

HALLE PARKER: So, really, at its core, this sediment diversion is really all about, like you were talking about, reconnecting the muddy Mississippi River to Louisiana’s dying wetlands– or at least some of them. And the hope is to do that, first, in one of our most degraded basins, which is located about a 40-minute drive south of New Orleans. And the state wants to construct this two-mile long concrete channel, redirecting as much water as possible from the river during the flood season into these now open bays. There used to be marsh there, but that’s all disappeared, for the most part.

And so once that river water leaves the channel and the diversion structure, it’ll end up slowing down. And the mud, the silt, the sands, and the clays that are inside of that water will start to fall out and build new deltas and wetlands. And the hope is that it’ll build up to 21 square miles over 50 years.

IRA FLATOW: And so this is going to benefit specifically whom?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah. So I mean, there are a lot of benefits to this gigantic project. If you talk to anyone in south Louisiana, especially the southeast, everyone agrees we need more land.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Right.

HALLE PARKER: So this land and the wetlands that we’re going to build are super important. It provides a critical buffer against hurricanes and storm surge, the same things that seem to be getting stronger with climate change. And this land will help protect the populated areas farther upriver from the diversion, like the greater New Orleans area. Because as more of that land slips away, the more vulnerable we are. So we’re trying to build that back up.

Plus, it’s not just the sand and the mud. It’s also the freshwater itself. Because as that land has been lost, the saltiness of the Gulf has actually migrated inward and inland. And that’s also transformed the basin over the past century or so. And so that fresh water will help it remain a diverse estuary, benefiting things like crawfish, which we love to eat down here in Louisiana, bass, crabs.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Well, it sounds great. But who could be against this thing?

HALLE PARKER: Well, there’s definitely drawbacks to a huge plan like this, too. The most vocal groups against it are residents, who could see more flooding, and seafood fishermen. And the state has a plan to try to deal with all that. But with the residents, there are a handful of communities that are outside of a levee system. And so they would see more flooding by having more water introduced, unfortunately.

And the state is trying to help by elevating roads and sewer systems or offering buyouts if needed. But when it comes to the fishers, it’s a little bit of a harder fix. Because just how the system is transformed, this would be an immediate shock to the system. And it would push out seafood, like shrimp. It would kill oyster beds that oyster harvesters rely on just because there would be so much fresh water.

And so these two groups have also just already been struggling due to other factors, and they think that this diversion could be what ends generations of fishermen in these families.

IRA FLATOW: Well, climate change, in the meantime, is going to keep changing coastal areas, right? Certainly, Louisiana’s coast. Could this plan actually work? Could it mitigate any of those effects?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah. So that’s what makes this project so special– or what’s supposed to make it so special– is it’s the only coastal restoration project in Louisiana with the ability to actually maintain land in the face of sea level rise. Which is what makes it so different and why so many advocates and scientists actually support it. The goal is really for this to be a self-sustaining project that also helps sustain some of the other projects that they have going on in that basin.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Halle Parker, environment reporter for the Coastal Desk at WWNO, in New Orleans.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.