Why Contraceptive Failure Rates Matter In A Post-Roe America

12:16 minutes

This story is a collaboration between Science Friday and KHN. It was written by KHN senior correspondent Sarah Varney.

Birth control options have improved over the decades. Oral contraceptives are now safer, with fewer side effects. Intrauterine devices can prevent pregnancy 99.6% of the time. But no prescription drug or medical device works flawlessly, and people’s use of contraception is inexact.

“No one walks into my office and says, ‘I plan on missing a pill,’” said obstetrician-gynecologist Dr. Mitchell Creinin.

“There is no such thing as perfect use, we are all real-life users,” said Creinin, a professor at the University of California-Davis who wrote a widely used textbook that details contraceptive failure rates.

Even when the odds of contraception failure are small, the number of incidents can add up quickly. More than 47 million women of reproductive age in the United States use contraception and, depending on the birth control method, hundreds of thousands of unplanned pregnancies can occur each year. With most abortions outlawed in at least 13 states and legal battles underway in others, contraceptive failures now carry bigger stakes for tens of millions of Americans.

Researchers distinguish between the perfect use of birth control, when a method is used consistently and correctly every time, and typical use, when a method is used in real-life circumstances. No birth control, short of a complete female sterilization, has a 0.00% failure rate.

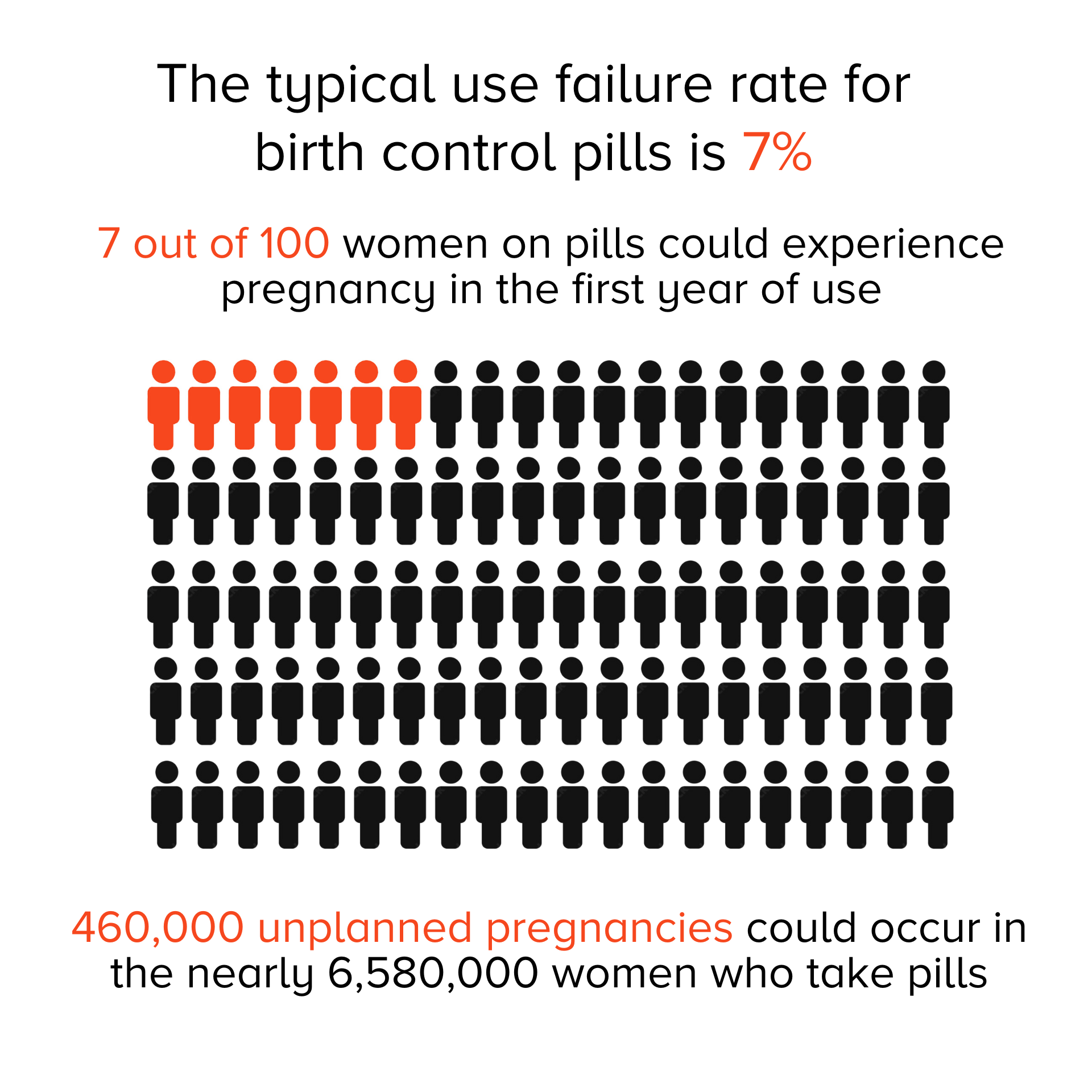

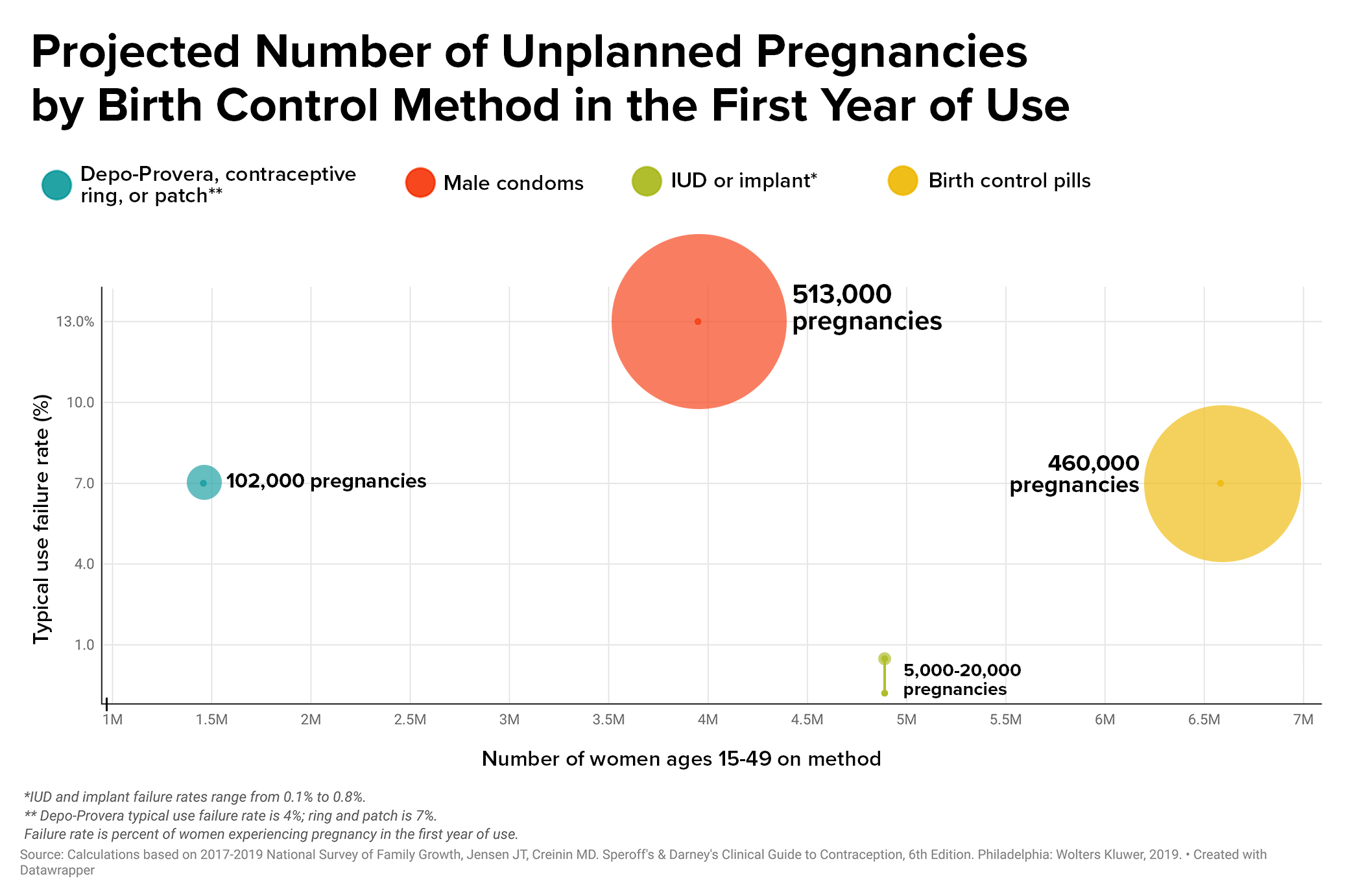

The failure rate for typical use of birth control pills is 7%. For every million women taking pills, 70,000 unplanned pregnancies could occur in a year. According to the most recent data available, more than 6.5 million women ages 15 to 49 use oral contraceptives, leading to about 460,000 unplanned pregnancies.

Even seemingly minuscule failure rates of IUDs and birth control implants can lead to surprises.

An intrauterine device releases a hormone that thickens the mucus on the cervix. Sperm hit the brick wall of mucus and are unable to pass through the barrier. Implants are matchstick-sized plastic rods placed under the skin, which send a steady, low dose of hormone into the body that also thickens the cervical mucus and prevents the ovaries from releasing an egg. But not always. The hormonal IUD and implants fail to prevent pregnancy 0.1% to 0.4% of the time.

Some 4.8 million women use IUDs or implants in the U.S., leading to as many as 5,000 to 20,000 unplanned pregnancies a year.

“We’ve had women come through here for abortions who had an IUD, and they were the one in a thousand,” said Gordon Low, a nurse practitioner at the Planned Parenthood in Little Rock.

Abortion has been outlawed in Arkansas since the Supreme Court’s ruling on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in late June. The only exception is when a patient’s death is considered imminent.

Those stakes are the new backdrop for couples making decisions about which form of contraception to choose or calculating the chances of pregnancy.

Another complication is the belief among many that contraceptives should work all the time, every time.

“In medicine, there is never anything that is 100%,” said Dr. Régine Sitruk-Ware, a reproductive endocrinologist at the Population Council, a nonprofit research organization.

All sorts of factors interfere with contraceptive efficacy, said Sitruk-Ware. Certain medications for HIV and tuberculosis and the herbal supplement St. John’s wort can disrupt the liver’s processing of birth control pills. A medical provider might insert an IUD imprecisely into the uterus. Emergency contraception, including Plan B, is less effective in women weighing more than 165 pounds because the hormone in the medication is weight-dependent.

And life is hectic.

“You may have a delay in taking your next pill,” said Sitruk-Ware, or getting to the doctor to insert “your next vaginal ring.”

Using contraception consistently and correctly lessens the chance for a failure but Alina Salganicoff, KFF’s director of women’s health policy, said that for many people access to birth control is anything but dependable. Birth control pills are needed month after month, year after year, but “the vast majority of women can only get a one- to two-month supply,” she said.

Even vasectomies can fail.

During a vasectomy, the surgeon cuts the tube that carries sperm to the semen.

The procedure is one of the most effective methods of birth control — the failure rate is 0.15% — and avoids the side effects of hormonal birth control. But even after the vas deferens is cut, cells in the body can heal themselves, including after a vasectomy.

“If you get a cut on your finger, the skin covers it back up,” said Creinin. “Depending on how big the gap is and how the procedure is done, that tube may grow back together, and that’s one of the ways in which it fails.”

Researchers are testing reversible birth control methods for men, including a hormonal gel applied to the shoulders that suppresses sperm production. Among the 350 participants in the trial and their partners, so far zero pregnancies have occurred. It’s expected to take years for the new methods to reach the market and be available to consumers. Meanwhile, vasectomies and condoms remain the only contraception available for men, who remain fertile for much of their lives.

At 13%, the typical-use failure rate of condoms is among the highest of birth control methods. Condoms play a vital role in stopping the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, but they are often misused or tear. The typical-use failure rate means that for 1 million couples using condoms, 130,000 unplanned pregnancies could occur in one year.

Navigating the failure rates of birth control medicines and medical devices is just one aspect of preventing pregnancy. Ensuring a male sexual partner uses a condom can require negotiation or persuasion skills that can be difficult to navigate, said Jennifer Evans, an assistant teaching professor and health education specialist at Northeastern University.

Historically, women have had little to no say in whether to engage in sexual intercourse and limited autonomy over their bodies, complicating sexual-negotiation skills today, said Evans.

Part of Evans’ research focuses on men who coerce women into sex without a condom. One tactic known as “stealthing” is when a man puts on a condom but then removes it either before or during sexual intercourse without the other person’s knowledge or consent.

“In a lot of these stealthing cases women don’t necessarily know the condom has been used improperly,” said Evans. “It means they can’t engage in any kind of preventative behaviors like taking a Plan B or even going and getting an abortion in a timely manner.”

Evans has found that heterosexual men who engage in stealthing often have hostile attitudes toward women. They report that sex without a condom feels better or say they do it “for the thrill of engaging in a behavior they know is not OK,” she said. Evans cautions women who suspect a sexual partner will not use a condom correctly to not have sex with that person.

“The consequences were already severe before,” said Evans, “but now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, they’re even more right now.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is an editorially independent, nationwide program of KFF (the Kaiser Family Foundation).

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Sarah Varney is a senior correspondent at Kaiser Health News in Monterey, Massachusetts.

Mitchell Creinin is a Professor in the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the Director of the Complex Family Planning Fellowship at the University of California – Davis in Sacramento, California.

Gordon Low is a Nurse Practitioner with Planned Parenthood in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Régine Sitruk-Ware is a Reproductive Endocrinologist and Distinguished Scientist in the Center for Biomedical Research of the Population Council in New York, New York.

Jennifer Evans is an Assistant Teaching Professor in the Department of Health Sciences at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts.

Alina Salganicoff is Director of Women’s Health Policy for the Kaiser Family Foundation in San Francisco, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

Since the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, we’ve been following the science behind reproductive health. SciFri producer Shoshannah Buxbaum, who’s been focusing on reproductive health, joins me now to talk about a key option for healthy reproduction– contraception.

Hi, Shoshannah.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Hi, Ira. I’ve been thinking a lot about how often contraception fails, how difficult it can be to access, and what this all means now that tens of millions of women live in states where abortion is a crime.

And in order to help piece this together, I’ve enlisted the reporting expertise of Sarah Varney, senior correspondent with Kaiser Health News. She’s a longtime health reporter who focuses on reproductive health.

Welcome, Sarah.

SARAH VARNEY: Thanks. It’s good to be here.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: So since the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, some medical clinics have seen a spike in demand for more effective birth control. But you’ve been reporting on a very important fact– no contraceptive is 100% effective.

SARAH VARNEY: That’s exactly right. And I wanted to gauge just how many unplanned pregnancies can occur because contraception doesn’t work flawlessly. So my first call was to a physician and researcher, who wrote the textbook on contraceptive failure rates.

MITCHELL CREININ: Mitchell Creinin. I am a professor and director of the Complex Family Planning Fellowship at the University of California, Davis.

SARAH VARNEY: I put to Dr. Creinin an argument I’ve heard during my reporting on abortion. And we had this idea, I think, that contraception should never fail, that there shouldn’t be a need for abortion, perhaps, because people can always prevent pregnancy.

MITCHELL CREININ: When someone gets into their car, they don’t go out and say, I think I’m going to get in a car accident today. The reason cars have seatbelts and airbags is because stuff happens even when we try our best not to have it happen. The same thing with using contraception.

SARAH VARNEY: I asked Dr. Creinin to do some math with the failure rates of some of the most commonly used contraceptives. In his textbook, Creinin distinguishes between typical use and perfect use. That’s when contraception is used without any error.

MITCHELL CREININ: There is no such thing as perfect use. We are all real-life users.

SARAH VARNEY: And for real-life users in real-life circumstances, the failure rate for oral contraceptives is 7%. Here’s the simple math.

MITCHELL CREININ: If there was 1 million women in the United States using a birth control pill, for example, at the end of one year, 70,000 unplanned pregnancies would occur in people saying, I’m using a birth control pill to prevent pregnancy.

SARAH VARNEY: More than 6 and 1/2 million women of childbearing age use oral contraceptive pills. That means the potential of about 460,000 unplanned pregnancies each year. And if that seems like a high number, wait until you hear about condoms. The typical failure rate is double that of oral contraceptives– 13%.

MITCHELL CREININ: Right. And that’s still better than not using anything. But that would mean, for a million couples using condoms, there would be 130,000 unplanned pregnancies within one year.

SARAH VARNEY: And even the most effective forms of birth control are no guarantee. The IUD, or hormonal intrauterine device, releases a hormone that thickens the mucus on the cervix, creating a barrier for sperm.

MITCHELL CREININ: There are electron microscope studies that show the sperm just kind of hit this brick wall of mucus and can’t get past it.

SARAH VARNEY: Copper IUDs work a bit differently. The high concentration of copper kills the sperm. Another highly effective method is an implant placed under the skin of the upper arm that slowly releases a hormone that prevents the ovaries from releasing an egg.

MITCHELL CREININ: Hormonal IUDs have that typical use failure rate of about 0.1 to 0.4. And copper IUDs have a typical use failure rate at about 0.8.

SARAH VARNEY: Nearly 5 million women in the US rely on IUDs and implants. Which means that even for those using top-notch birth control, up to 19,000 will become pregnant within a year.

At the Planned Parenthood in Little Rock, Arkansas, nurse practitioner Gordon Low has treated these shocked patients.

GORDON LOW: We have had women come through here for abortions who had an IUD in, and they were the 1 in 1,000.

SARAH VARNEY: Abortion has been completely outlawed in Arkansas since the Supreme Court’s ruling in late June. The only exception is when the death of a pregnant woman is imminent.

GORDON LOW: There is nothing that is 100% effective short of never having sex. That is it.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: All right, Sarah. You just walked us through some really sobering stats. But why can’t scientists develop a contraceptive that works all the time every time?

SARAH VARNEY: That was my question exactly. I called up one of the world’s leading researchers on contraception and asked her that question.

REGINE SITRUK-WARE: Well, first, I would say that, in medicine, there is never any 100%.

SARAH VARNEY: This is Regine Sitruk-Ware.

REGINE SITRUK-WARE: I’m a reproductive endocrinologist, and I work at the Population Council in New York.

SARAH VARNEY: Dr. Sitruk-Ware says an IUD might fail because the health care provider didn’t place the device properly or–

REGINE SITRUK-WARE: In other situations, you can have people who take specific drugs for other diseases that would interfere with the molecule, the hormones, that is in the system. And therefore, this contraceptive is less active. And so there is a failure.

SARAH VARNEY: For example, some HIV and tuberculosis medications, and even the herbal supplement St. John’s wort, can intervene in the processing of certain birth control pills. And then there’s just daily life, which is hectic.

REGINE SITRUK-WARE: The perfect use is always very difficult. You may have delay in taking your next pill or delay in inserting the next month of the vaginal ring.

SARAH VARNEY: And then there are factors like weight. Certain emergency contraception, including Plan B, may not work in people who weigh more than 165 pounds because the single dose of hormone is weight dependent. Even vasectomies have a failure rate. Here’s Dr. Creinin again.

MITCHELL CREININ: A vasectomy is removing a small part of the tube that takes the sperm from the storage facility that’s right above the testicle, where all the sperm that is made is stored. And the body naturally wants to heal, right? If you get a cut on your finger and you just put a Band-Aid over it, the skin seals back up. So if you have a gap in a tube, the body naturally wants it to grow back together. And that’s one of the ways in which it fails.

SARAH VARNEY: For now, vasectomies and condoms are the only birth control options for men. But Dr. Sitruk-Ware is developing a new method, a gel that a man applies to his shoulders, where the skin is thinner and generally less hairy, that can temporarily block sperm production.

REGINE SITRUK-WARE: At this stage, we saw really good acceptability by the couple and no pregnancy so far.

SARAH VARNEY: About 350 couples are in the transdermal gel study so far. And Dr. Sitruk-Ware is on track to begin a large-scale trial next year. You’ve come much further in the development of a new male contraceptive than people have in decades. There’s always been this promise of a male contraceptive. Is the difficulty in developing male contraception more of a scientific problem or is it more of a social or a cultural one?

REGINE SITRUK-WARE: I think we can say all of it. Scientifically, it takes more time to suppress the sperm production– 90 days– than suppressing ovulation in women, which is every month. Also, it’s a social situation, where the male contraception is taken by the man. But if there is a failure, his female partner is at risk of pregnancy.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: But this type of male contraception is still a long way away from hitting pharmacy shelves. And there have been so many fits and starts in this area of research. But there are other dynamics at play here, too. And Sarah, you looked into something that many straight women may be familiar with but don’t talk about publicly.

SARAH VARNEY: Yeah. We talked about condom use earlier. And getting a partner to use a condom can require negotiation or persuasion. Those are skills that Jennifer Evans, an assistant teaching professor at Northeastern University, studies closely.

JENNIFER EVANS: So stealthing, or non-consensual condom removal, is where one partner puts on a condom, but then removes the condom either before or during sexual intercourse without the other partner’s knowledge or consent.

SARAH VARNEY: When I spoke to Evans, I had just been interviewing girls about teen pregnancy for another story. One of the teens described how a guy pretended to rip the condom wrapper open, but then apparently never used it. She became pregnant and now has a four-month-old baby.

JENNIFER EVANS: A lot of these stealthing cases, women don’t necessarily know that the condom has been used improperly. It means that they can’t engage in any kind of preventative behaviors, like taking a Plan B or even going and getting an abortion in a timely manner.

SARAH VARNEY: In any of your research, have you asked men what their motivation would be to even do this?

JENNIFER EVANS: Generally, what we find in the research and the literature, it says that men usually engage in this behavior whenever they have a more severe history of sexual aggression towards women, or that men are doing it for the thrill of engaging in a behavior that they know is not OK. And a lot of them also report that they do it from a physical pleasure standpoint.

The consequences were already severe before, but now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, I would argue that they’re even more worse right now.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: I mean, that’s just sort of heartbreaking in a lot of ways. Contraception is really more complicated than I’d previously thought. And of course, unfortunately, no conversation about American health care would be complete without some nod to how many people struggle to get even the basic care that they need. So how does that whole dynamic affect access to birth control?

SARAH VARNEY: There are 7.9 million women of reproductive age in the US who are uninsured. So they have no coverage for birth control. The states that have banned or severely restricted abortion, in general, have far higher rates of people without health insurance. That includes Texas, where one in five people have no health coverage.

Alina Salganicoff is the director of Women’s Health Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. She has spent decades studying this issue.

ALINA SALGANICOFF: We have a patchwork of programs and services that provide contraceptive care in the United States. We have private insurance. We have Medicaid. We also have the federal Title X Family Planning Program.

SARAH VARNEY: But Salganicoff says this patchwork has gaps. Not everyone has private insurance or Medicaid or lives near one of these federally funded clinics that provide free or low-cost birth control.

ALINA SALGANICOFF: So there is definitely cases where women fall through the gaps and lose coverage and have problems accessing and affording birth control.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: So Sarah, we’ve covered a lot of ground here– how the numbers of unintended pregnancy adds up when birth control fails, a possible male contraceptive, and the difficulties of navigating sexual relationships. So has the overturn of Roe v. Wade affected access to birth control?

SARAH VARNEY: We’re starting to get some hints from around the country of how the Court’s ruling might affect birth control. I spoke to several clinic directors in Arkansas, for example, who are no longer prescribing emergency contraception because they’re not sure how the state’s abortion ban will be enforced.

And recently, the University of Idaho issued legal guidance to faculty and staff, that they can no longer offer any birth control to students. Condoms can only be provided, quote, for the purposes of helping prevent the spread of STDs, but not for birth control.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: This is something we’ll be following closely. Thanks so much, Sarah.

SARAH VARNEY: Oh, thank you, Shoshannah.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Sarah Varney is a senior correspondent with Kaiser Health News. And I’m Shoshannah Buxbaum.

If you want to dig deeper into the data on contraceptive failure rates and read more of Sarah’s reporting, go to sciencefriday.com/contraception.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.