How A $2 Billion U.S. Plan To Save Salmon In The Northwest Is Failing

7:32 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Tony Schick, Oregon Public Broadcasting, and Irena Hwang, ProPublica, featuring photography by Kristyna Wentz-Graff, Oregon Public Broadcasting, was originally published on ProPublica.

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Tony Schick, Oregon Public Broadcasting, and Irena Hwang, ProPublica, featuring photography by Kristyna Wentz-Graff, Oregon Public Broadcasting, was originally published on ProPublica.

CARSON, Wash.—The fish were on their way to be executed. One minute, they were swimming around a concrete pond. The next, they were being dumped onto a stainless steel table set on an incline. Hook-nosed and wide-eyed, they thrashed and thumped their way down the table toward an air-powered guillotine.

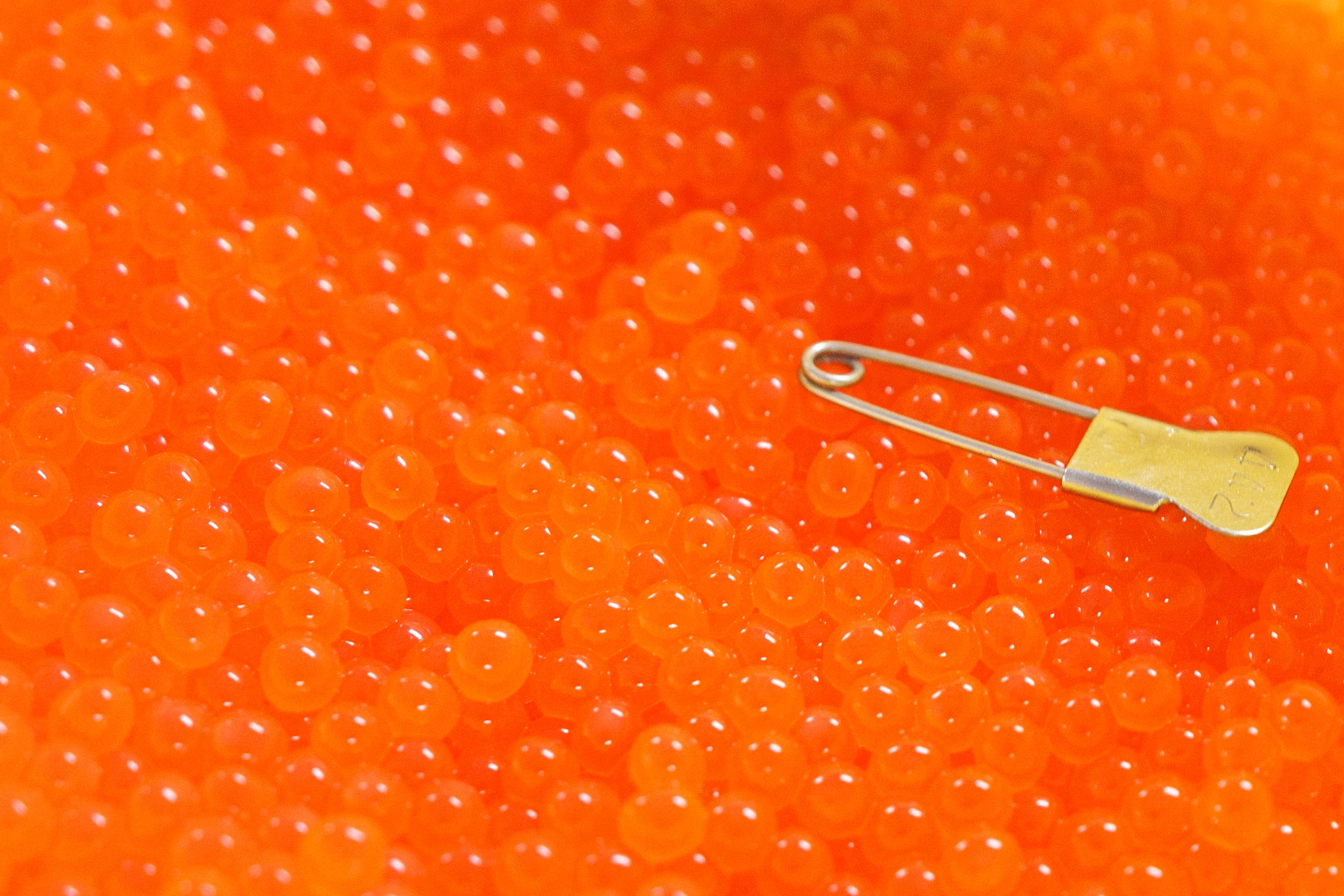

Hoses hanging from steel girders flushed blood through the grated metal floor. Hatchery workers in splattered chest waders gutted globs of bright orange eggs from the dead females and dropped them into buckets, then doused them first with a stream of sperm taken from the dead males and then with an iodine disinfectant.

The fertilized eggs were trucked around the corner to an incubation building where over 200 stacked plastic trays held more than a million salmon eggs. Once hatched, they would fatten and mature in rectangular concrete tanks sunk into the ground, safe from the perils of the wild, until it was time to make their journey to the ocean.

The Carson National Fish Hatchery was among the first hatcheries funded by Congress over 80 years ago to be part of the salvation of salmon, facilities created specifically to replace the vast numbers of wild salmon killed by the building of dozens of hydroelectric dams along the Northwest’s mightiest river, the Columbia. Tucked beside a river in the woods about 60 miles northeast of Portland, Carson has 50 tanks and ponds surrounded by chain-link fencing. They sit among wood-frame fish nursery buildings and a half-dozen cottages built for hatchery workers in the 1930s.

Today, there are hundreds of hatcheries in the Northwest run by federal, state and tribal governments, employing thousands and welcoming the community with visitor centers and gift shops. The fish they send to the Pacific Ocean have allowed restaurants and grocery seafood counters to offer “wild-caught” Chinook salmon even as the fish became endangered.

The hatcheries were supposed to stop the decline of salmon. They haven’t. The numbers of each of the six salmon species native to the Columbia basin have dropped to a fraction of what they once were, and 13 distinct populations are now considered threatened or endangered. Nearly 250 million young salmon, most of them from hatcheries, head to the ocean each year—roughly three times as many as before any dams were built. But the return rate today is less than one-fifth of what it was decades ago. Out of the million salmon eggs fertilized at Carson, only a few thousand will survive their journey to the ocean and return upriver as adults, where they can provide food and income for fishermen or give birth to a new generation.

Federal officials have propped up aging hatcheries despite their known failures, pouring more than $2.2 billion over the past 20 years into keeping them going instead of investing in new hatcheries and habitat restorations that could sustain salmon for the long term. At the largest cluster of federally subsidized hatcheries on the Columbia, the government spends between $250 and $650 for every salmon that returns to the river. So few fish survive that the network of hatcheries responsible for 80% of all the salmon in the Columbia River is at risk of collapse, unable to keep producing fish at meaningful levels, an investigation by Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica has found.

These failures are all the more important because hatcheries represent the U.S. government’s best effort to fulfill a promise to the Northwest’s Indigenous people. The government and tribes signed treaties in the 1850s promising that the tribes’ access to salmon, and their way of life, would be preserved. Those treaties enshrined their right to fish in their “usual and accustomed places.” The pacts between sovereign nations did not stop the U.S. from moving forward with a massive decades-long construction project in the middle of the 20th century: the building of 18 dams that transformed a free-flowing river into a machine of irrigation, shipping and hydroelectric power.

The dams meet nearly 40% of today’s regional electricity needs. But they decimated wild salmon.

Many species of salmon are at or near their lowest numbers on record. Native fishermen say their way of life has been stolen from them and from future generations. But the government didn’t invest in making hatcheries better equipped to grow more resilient and abundant stocks. Instead, officials ushered in endangered species restrictions. They knew that hatchery fish were genetically weaker than wild salmon, so they put limits on the number of hatchery fish that could be released into rivers, where they might spawn with wild fish and weaken the gene pool. These restrictions hampered the productivity of the hatcheries, squeezing tribal fishing even more.

In recent years, salmon survival has dropped to some of the worst rates on record. The numbers of returning adult salmon have been so low that dozens of hatcheries have struggled to collect enough fish for breeding, putting future fishing seasons in jeopardy.

Each passing year of poor returns worsens the outlook for salmon. While salmon runs fluctuate from year to year and this year’s returns have been higher than those of the past few years, human-caused climate change continues to warm the ocean and rivers, and the failure to improve salmon survival rates has left the region’s tribes facing a future without either wild or hatchery fish. Federal scientists project that salmon survival will decline by as much as 90% over the next 40 years.

The federal agencies responsible for more than 200 hatchery programs—including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Northwest Power and Conservation Council—have failed to implement recommendations from their own scientists about how to improve outcomes at the hatcheries they support.

Allyson Purcell is the director of West Coast hatcheries for NOAA, which oversees endangered salmon recovery, sets regulations for hatcheries and funds roughly a third of all Columbia River hatchery production. In an interview, she conceded that federal hatchery reform efforts have historically focused on saving wild salmon, but said that her agency is now researching ways to create more resilient hatchery fish.

“As soon as we have actionable science, we will implement changes,” Purcell said. She also acknowledged that hatcheries will need to change to sustain fish populations as the climate continues to change.

“We want to stay nimble,” she said. “In some cases you may want to change the goal of the hatchery. If you find that you need to rely on it to keep a population from going extinct, you’re going to operate that hatchery program differently.”

People like John Sirois, a former chair of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in northeast Washington, have been waiting a long time for changes. Nearly a decade ago, he cut the ribbon at the opening of the Chief Joseph Hatchery, 545 miles upriver from the mouth of the Columbia. That hatchery, one of 23 facilities overseen by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, opened in 2013.

But it is now struggling to return enough fish, and the upper Columbia’s spring Chinook population has fallen to one of its lowest levels on record. Last year the Colville Tribes, whose diet was once as much as 60% salmon, caught less than one fish for each of its 10,000 people.

“Despite all the efforts that we’ve done, the salmon run is looking pretty on the ropes.” Sirois said. “If it’s more difficult for hatcheries to produce salmon, it is the beginning of the end.”

There are many reasons that Columbia River salmon die, whether they were born in the wild or in hatcheries. Millions don’t survive their trip down the river, which has become a gantlet of dams and slackwater reservoirs, hot and polluted waters, and invasive predators. Millions more die in the ocean or get snared by commercial fishing ships, ending up as grocery fillets or pet food before they can return upriver toward their spawning grounds.

Some die-off is natural. But the dismal survival rates of salmon bred on the Columbia today are neither natural nor sustainable.

Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica examined the yearly survival of eight Columbia River Basin hatchery populations of vulnerable salmon and steelhead trout, detected at a federal dam on their way out to sea as juveniles and on their way back upriver as adults. This dam-to-dam measure provides one of the only consistent indexes of how well salmon are surviving. But it’s a high-end estimate, because it only measures how well they’re surviving in the ocean. These numbers don’t account for the millions of juvenile fish that die migrating downriver before they’re counted at the dam or the many adults who pass the dam but die before reaching their destination upriver. Our analysis of the publicly available data provides a high-level and easily understandable snapshot of hatchery performance; previously, assessing the health of the hatchery system would have required combing through thousands of pages of government reports and academic research.

Even with this generous estimate, however, the survival rates of these hatchery fish have been well short of the established goals for rebuilding salmon populations, according to the Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica analysis.

According to our analysis, salmon populations released from 2014 to 2018, the most recent years for which complete data was available, had some of the worst survival rates on record. In that time period, none of the eight populations had average returns exceeding 4%, the threshold necessary for a population to recover, which was adopted by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council and vetted by independent panels of experts. But even in the previous six years, when ocean conditions were favorable for salmon, only two achieved average returns above 4%.

That 4% goal was established for wild populations, but in a 2015 report to Congress, 17 scientists recommended that survival rates of hatchery fish would have to be high relative to wild fish “to effectively contribute to harvest and/or conservation.”

Most hatcheries, however, aren’t even aiming to meet the council’s recovery goals. Some aim to get less than half a percent of their fish back. But lately, they aren’t even getting that.

“It’s not self-sustaining. We don’t have the numbers,” said Aaron Penney, a member of the Nez Perce who spent more than 20 years managing his tribe’s hatchery on the Clearwater River in Idaho. Penney, now a biologist for the Coeur d’Alene Tribe in northern Idaho, says raising hatchery fish in worsening river and ocean habitat is like “putting a finger in a dike to stop a leak.”

Records obtained from NOAA show that over the past five years, dozens of hatchery programs have fallen short of their typical production levels, some by more than half. Some have tried to address that shortfall by capturing more wild fish to breed. Others used eggs that were shared by nearby hatcheries.

But major shortages across the Columbia basin in 2018 and 2019 left hatcheries scrambling to find enough egg-bearing female fish. Tribal hatcheries, which are located farther upriver where salmon face a longer, harder journey, bore the brunt. They’ve been planning for shortages to become commonplace as rivers and the Pacific Ocean get hotter.

In 2019, Idaho’s Nez Perce Tribe needed an influx of hundreds of fish from hatcheries 300 miles away in Washington to keep breeding salmon. Staff at the time called it a “dire emergency.”

In central Washington, the Yakama Nation’s share of eggs was so small that its hatchery on the Klickitat River was down to 30% of the number of fish it usually raises.

“It’s impacting the Indians a lot, man,” said Shane Patterson, a member of the Yakama Nation who fishes the Klickitat and works as a catch monitor for the tribe. “The seasons ain’t as long as they used to be, they’re smaller runs, everything.”

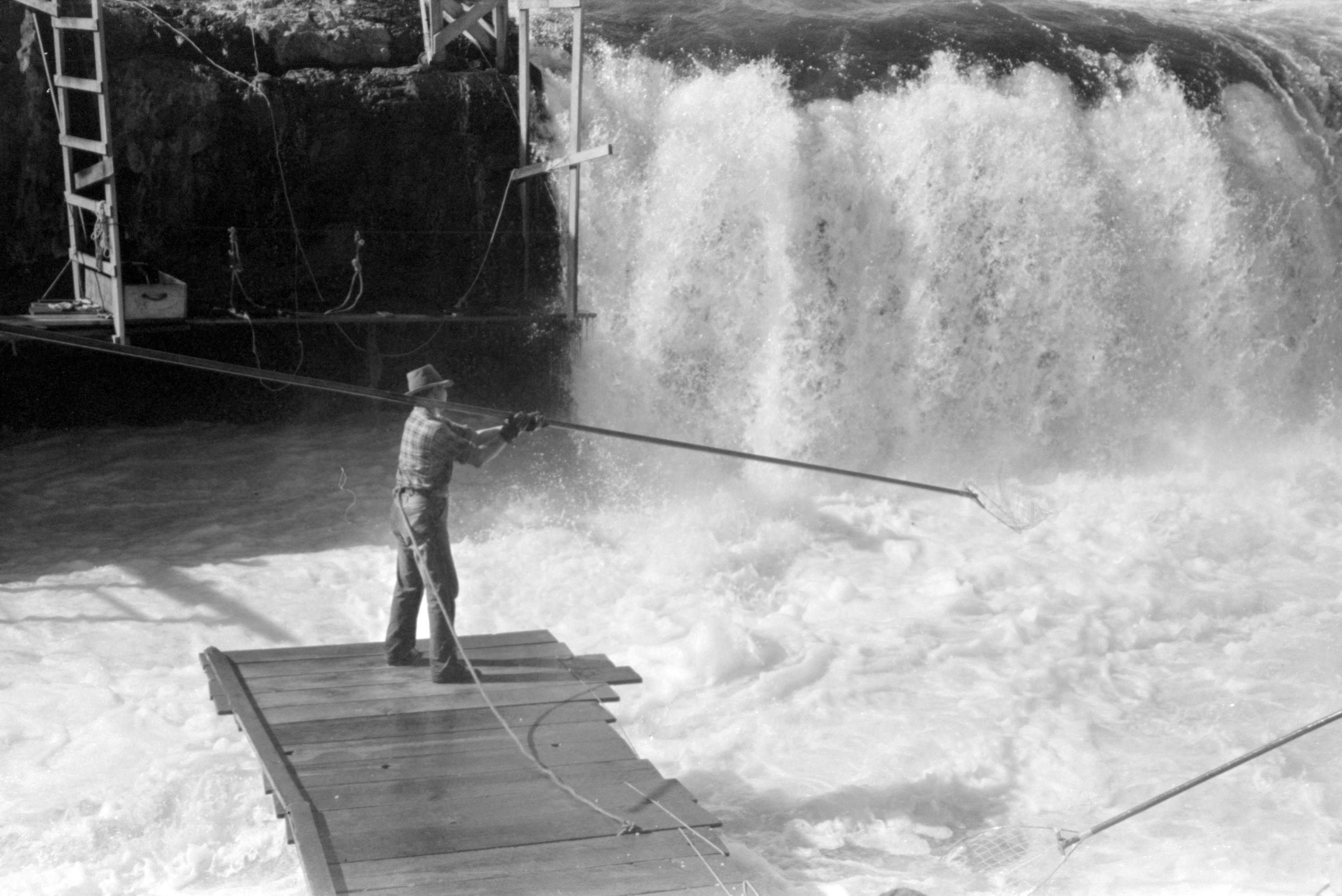

Between spring and fall, Patterson and his friend and fellow tribe member Chance Fiander spend evenings atop plywood scaffolds built into the rock face of the Klickitat River canyon, plunging dip nets 30 feet into the waters, awaiting the jolt of a salmon fighting its way upstream.

The Klickitat hatchery provides Patterson and Fiander fish to catch for their families and for the tribe’s longhouses, spiritual gathering centers that need salmon for weekly ceremonies, annual feasts, funerals and coming-of-age ceremonies known as name givings.

This April, there were so few spring Chinook salmon for the annual spring feast Patterson attended—held to honor the first foods of the new year—that it took donated bags of frozen salmon to feed everyone at the longhouse that day.

“That defeats the purpose. That ceremony was for that first food coming up the river,” Patterson said. “It’s just … kinda backwards.”

From the very start, federal agencies had evidence of hatcheries’ failures. But they didn’t leave themselves any other solutions.

Within two decades of enshrining in treaties the right of Northwest tribes to fish for salmon as they always had, the United States government had let commercial fishing deplete salmon runs to the point that the nation’s fish commissioner was devising ways to produce more of them.

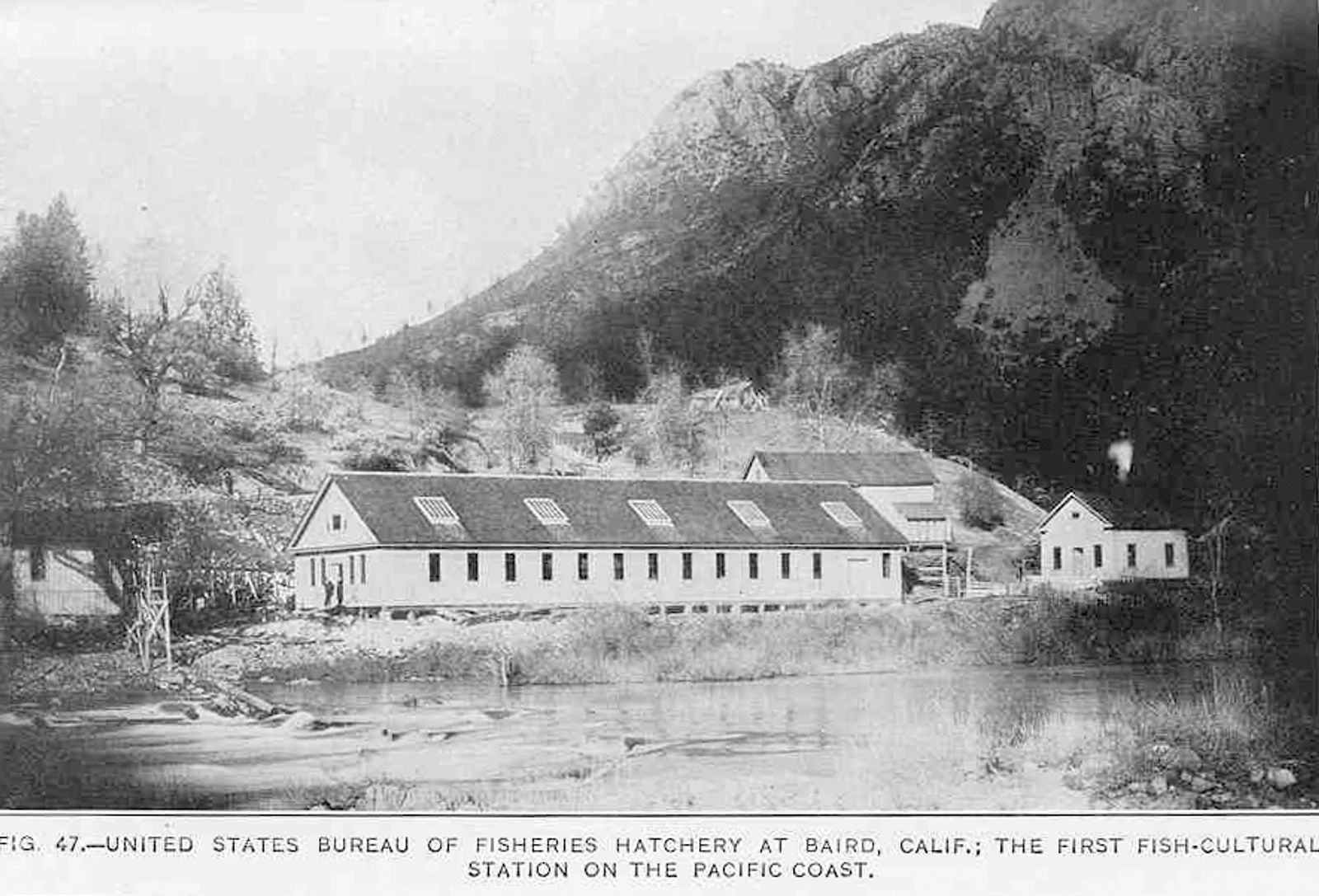

In 1872, Spencer Baird, the founder of the agency now known as NOAA Fisheries, built the West Coast’s first salmon hatchery in California and three years later recommended the same solution for the Columbia River’s problems with habitat loss and overfishing.

Baird told fishermen and cannery operators that artificial production would “maintain the present numbers indefinitely, and even… increase them.” Oregon fishing commissioners seized on the idea, declaring that salmon required less labor and care to raise than vegetables.

But the early hatchery efforts faded. By the 1920s, the first analysis of hatcheries at the time found “no evidence” to suggest hatcheries had effectively conserved salmon. Similar research reached the federal Department of Fisheries, a precursor to what is now NOAA Fisheries, in 1929. Amid the poor results and the Great Depression, state and federal fisheries agencies largely abandoned costly large-scale efforts to breed salmon.

Overfishing was the first blow to salmon populations. Dams were the biggest. Between 1933 and 1975, 18 dams were built on the Columbia and Snake rivers. Nearly half of all salmon habitat in the Columbia basin was completely blocked; the rest was drastically altered as humans turned a free-flowing river system into a series of reservoirs and built farms and communities.

The dams destroyed the river’s most important tribal fishing sites and pushed many populations of wild salmon nearly to the point of extinction or wiped them out entirely. But despite the hatcheries’ failures in the early days, the federal government turned to them after damming up the Columbia and the Snake. It was the best offer officials made to the tribes that depended on salmon.

The federal government laid out its position in a 1947 memo, signed by the secretary of the interior: “The overall benefits to the Pacific Northwest from a thorough-going development of the Snake and Columbia are such that the present salmon run must be sacrificed. Efforts should be directed toward ameliorating the impact of this development upon the injured interests and not toward a vain attempt to hold still the hands of the clock.”

Biologists for the Fish and Wildlife Service knew at the time there was no evidence to suggest hatcheries could make up for the impact. But four of those scientists, including the author of the 1920s research casting doubt on hatcheries, suggested hatcheries anyway; after seeing the government’s plans for dam construction, biologists knew that preserving existing salmon runs would be essentially impossible.

Hatcheries again failed to offset the damage. By the late 1970s, hatcheries were releasing three times more juvenile salmon than scientists estimate the wild fish ever produced themselves. But fish counts at federal dams showed that while tens of millions more juvenile salmon were heading downriver each year, the number of returning adult salmon kept dropping.

Part of the problem was how the fish were bred. Salmon have lasted millions of years, across multiple ice ages, because of the diversity in their populations. But in the hatcheries, that diversity started to disappear and fish developed traits that make it harder for them to survive in the wild.

Rob Jones, the former head of NOAA’s hatchery division, said the agencies running hatcheries have known this for as long as he can remember, which is why they have always depended on wild populations to bolster their stocks.

“Without infusing hatcheries, from time to time, with better-fit fish,” Jones said, “hatchery fish might taper off and not return anymore. Because their fitness is just so poor.”

In the early 1990s, several salmon populations landed on the endangered species list. Scientists and environmental advocates began to argue that hatchery fish posed a threat to wild salmon recovery.

“Fisheries scientists, by promoting hatchery technology and giving hatchery tours, have misled the public into thinking that hatcheries are necessary and can truly compensate for habitat loss,” Ray Hilborn, a prominent fisheries scientist at the University of Washington, wrote in a 1992 paper. “Hatchery programs that attempt to add additional fish to existing healthy wild stocks are ill advised and highly dangerous.”

By the end of the 1990s, a panel of scientists for the Northwest Power and Conservation Council concluded that hatcheries had failed in their objective to mitigate habitat damage and were harming wild populations by competing for food and spreading weaker genes. And, they noted, other scientific reviews had reached the same conclusion.

“Scientists and fish culturists should be concerned about the findings of three independent scientific panels that concluded hatcheries have generally failed to meet their objectives,” they wrote.

Congress created a task force to reform hatcheries in 2000, aiming to minimize competition between wild and hatchery fish and to keep weaker hatchery-fish genes out of the wild. Soon, hatcheries faced limits on which fish they could breed, how many wild fish they could capture, how many fish they could release, and how many of their fish were allowed to escape to spawn in the wild. Each hatchery program now requires a genetics management plan.

“There was a lot of work on genetics the past couple of decades, and that’s because that’s probably where our biggest concern was,” said Purcell, who succeeded Jones as head of NOAA hatcheries.

But as it focused on wild genetics, NOAA’s reforms largely ignored how hatcheries grow and release their fish. The agency did not require updates to outdated facilities, nor did it order changes to how hatchery fish were penned, fed or released.

Tribes had begun experimenting with new methods of breeding in their own hatcheries. At its hatchery in Cle Elum, Washington, the Yakama Nation painted concrete tanks to match streambeds, tried filling them with woody debris found in streams, and used underwater feeding tubes so fish didn’t get used to being fed at the surface by humans. They bred captured wild fish instead of hatchery stock and used a collection of earthen ponds to acclimate fish to the wild before they’re released. They documented some success at increasing abundance while minimizing the harm to wild genetics.

But endangered species regulations and environmental lawsuits alleged that releases of hatchery fish were threatening wild salmon and compromising their recovery. Tribes found that their only tool for putting fish back into rivers—and for exercising their treaty rights—was under threat.

The National Congress of American Indians in 2015 issued a resolution calling for the protection and maximization of hatchery production. In it, the tribes said that salmon production had been “reduced, restricted, and threatened” by endangered species protections, lack of funding and inaction by NOAA, adding that “a disproportionate burden of conservation” had been “placed on the tribal harvest and hatchery requirements.”

Purcell said NOAA has for many years been backlogged in reviewing hatcheries to make sure their breeding programs adequately protected wild fish. Those delays left hatcheries exposed to lawsuits from environmental groups that have blocked or reduced releases of hatchery fish. Purcell said the agency to date has reviewed about 75% of hatchery programs across Oregon, Washington, California and Idaho.

Purcell acknowledged concern for wild fish has led to some hatchery reductions, but said the agency has tried to avoid that when possible for the sake of tribes.

“NOAA Fisheries understands how important hatchery programs are to the tribes,” she said, “so we work hard to find solutions that work for all involved.”

When salmon return each June to north-central Washington’s Icicle Creek, Sirois, the former chair of the Colville Tribes, drives with a rod and tackle box to the Leavenworth Fish Hatchery, where he sleeps in his car so he can be there when the sun comes up.

He’ll spend a weekend casting for salmon from Icicle Creek. During last June’s run, Sirois fished beside his cousin, with his young nephew perched atop a concrete bridge, watching from above. Across the water, his friend Jason Whalawitsa was fishing with his son atop scaffolds they had built.

The Wenatchi people, part of 12 bands making up the Colville Tribes, spent decades battling in court to reclaim their legal right to fish for salmon in Icicle Creek.

Now, they worry how long the supply of fish will last.

“Our warmer ocean waters don’t allow our fish to get here,” Whalawitsa said.

Salmon numbers have always fluctuated, but salmon biologists say the latest downturn is different: Climate change is making temperatures increasingly inhospitable to salmon, which need cold water. They’ve died by the hundreds of thousands in unusually hot rivers. And in warmer oceans, fish starve without adequate food.

A 2021 study led by NOAA ecologist Lisa Crozier found that warming ocean temperatures could cause salmon survival to decline by roughly 90% within the next 40 years.

“We can imagine all kinds of new situations that could occur. Unfortunately, most of them don’t seem to be favorable for salmon,” Crozier said.

The obstacles to saving salmon are myriad. Large swaths of the Columbia River Basin remain impaired by the effects of excessive heat and chemical pollution, and biologists say habitat restoration efforts are far behind what is needed to give salmon a real chance of rebounding. Advocates of removing the four dams on the lower Snake River to save salmon have gotten the attention of elected officials, but that would only benefit one subset of the basin’s salmon. It wouldn’t help the Wenatchi on the upper Columbia. And salmon there and elsewhere would still need a major boost in fitness to survive the ocean journey.

But Crozier’s study also recommended “desperately needed” actions to restore freshwater habitat, improve river flows and change hatchery practices to give salmon a better chance in the ocean.

“My biggest concern about publishing that paper was that people would say, ‘Oh, salmon are doomed. Let’s give up on them,’” Crozier said. “It’s not hopeless.”

Barry Berejikian, the top hatchery scientist at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center, agrees. He points to changes in fish tanks, water temperature and feeding schedules that can all increase hatchery fish’s survival odds. Facilities could also adjust how many fish are released and when: Longtime hatchery philosophy has been to flood the river with fish. But scientists have found that overloading the environment with too many fish can slow population growth, and that varying release times gives fish a better chance of survival.

As climate change damages the habitats of wild salmon, hatchery fish become all the more important.

“As we increasingly rely on them, we need to do them better,” Berejikian said of hatcheries. “Right now, the emphasis is not there.”

Officials at federal agencies governing hatcheries said they know salmon survival needs to improve, but demurred when asked about adopting the strategies Berejikian mentioned.

Most production at the 13 hatcheries run by the Fish and Wildlife Service is governed by legal agreements or settlements, giving the agency little flexibility, spokesperson Brent Lawrence said. He touted the agency’s success in keeping fish alive while they’re at the hatchery and said that fish survival in the wild is largely outside the agency’s control.

“We strive to release the healthiest salmon possible from our hatcheries to give the fish the best chance of survival,” Lawrence said.

Guy Norman, chair of the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, acknowledged changes are needed at hatcheries to produce stronger fish. But the council’s latest program called for no such changes. Norman said the council would help facilitate research and improvements, but that it has a limited role in prescribing operations at the state and tribal hatcheries in its program. However, the council has ordered changes in the past, such as stipulating that all hatcheries funded through its program needed to follow recommendations for protecting wild salmon.

Purcell, the NOAA hatcheries official, said her agency is limited in what it can require of hatcheries if the changes aren’t directly impacting an endangered population. And, because most of the region’s hatchery facilities are between 40 and 100 years old, she said recommended improvements like more natural rearing conditions “are not an option without a major rebuild.”

According to documents obtained from NOAA, much of the Columbia River Basin’s hatchery tanks and rearing facilities are near the end of their lifespans, and the basin’s capacity for hatchery production has diminished as failing infrastructure has been decommissioned or put into limited operation.

“That creates a lot of limitations to what we can implement,” Purcell said.

Existing operations at Northwest hatcheries are already underfunded by hundreds of millions of dollars, and in some cases parts of their infrastructure have literally crumbled and killed thousands of fish in the process.

At the Lookingglass Hatchery in northeast Oregon, outdated concrete “fish ladders” meant to help salmon escape upstream to spawn are instead blocking them, but the hatchery doesn’t have the $3.4 million needed to fix the problem. Meanwhile, the Lyons Ferry Hatchery in southeast Washington lost 250,000 fish this year because of a crumbling rubber gasket. Last year, it spent more than $5 million on a burst pipe and a pump failure.

In all, records show staff at federally funded hatcheries have identified more than $320 million in repairs and equipment upgrades they can’t make unless the government provides funding.

Congress has kept hatchery funding essentially flat for more than a decade, leaving those needs unaddressed. Sen. Maria Cantwell, a Democrat from Washington, sought to include $400 million for hatcheries as part of President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better plan. It would have been the single largest expenditure on hatcheries ever. That effort failed along with the bill. Cantwell did not respond to requests for comment.

Overhauling hatcheries to withstand climate change will cost hundreds of millions more. For instance, the Fish and Wildlife Service predicts that warming waters will lead to more disease and harm the growth of its fish, and that droughts could lead to water shortages on site. The agency has not yet requested additional funding to address what it calls “climate vulnerabilities” at Leavenworth or elsewhere.

More than a decade ago, Whalawitsa and his son Chris began fishing beside the Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery, where the current system only supports about half the promised production levels.

Whalawitsa and Chris fish hook-and-line by day and with traditional dip nets all night, trying to fill orders for tribal elders, family members and sick neighbors to help sustain them through winters on the reservation.

“We’re doing the best we can to keep this alive,” Whalawitsa said. “All I can do is pray and hope that this gets better because I want to see my grandchildren fish this.”

When they first started, they’d easily fill five coolers in a single trip and end up racing back and forth to the reservation to make room for more.

Now, they say, they’re lucky to fill one.

Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica obtained data from Columbia Basin Research at the University of Washington describing fish in several salmon and steelhead trout populations that were embedded with electronic tags. Tagged fish can be detected by special technology, often at dams, and tag data can provide a window into fish migration and survival. Our approach took a basin-wide view of the hatchery program to create a meaningful, accessible and representative picture of hatchery efforts to support vulnerable salmon and steelhead populations in the region.

We focused our analysis on eight fish populations, all of them Columbia River Basin stocks that are highly vulnerable and monitored by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration with the goal of restoring populations to healthy and harvestable levels. Focusing on fish populations that originated in the middle and upper Columbia and Snake rivers had two benefits: First, these were areas that were significantly impacted by the building of hydropower dams in the basin, and second, these were regions for which data was available. The upper Columbia River spring Chinook and Snake River sockeye populations are listed as endangered under the 1973 Endangered Species Act. The Snake River fall Chinook, Snake River spring/summer Chinook, Snake River steelhead and upper Columbia River steelhead populations are listed as threatened. The Mid-Columbia Coho Restoration Program includes all coho released in the Wenatchee and Methow basins, and the population was considered by NOAA for designation as threatened or endangered, as were upper Columbia River summer/fall Chinook; though these populations ultimately were not listed, they are still monitored by Columbia Basin Research and NOAA. These eight monitored populations are supported by more than 30 artificial propagation programs along the Columbia River and its tributaries.

The University of Washington’s Columbia Basin Research center provides data about these eight populations at any one of three federal dams: Bonneville Dam, Lower Granite Dam and McNary Dam. The tags, called passive integrated transponders, help generate data including the number of tagged juveniles released each year on their outbound journey downriver and the number of fish from each release year that were later detected as adults returning upriver from the ocean. Comparing these two quantities taken at Bonneville Dam, the nearest dam to the ocean on the Columbia River, provides an estimate of how many fish survived the ocean.

We calculated survival rates across two time periods: 2008-2013 and 2014-2018. During the first period, coastal conditions and climate conditions in the Pacific Ocean were particularly favorable for salmon and steelhead trout. Conditions changed around 2014, the beginning of our most recent span of data. Though Chinook, coho, sockeye and steelhead trout all mature at different times and follow distinct migration patterns, the majority of adult fish from these species return to fresh water to spawn after four years in the ocean, which is why we ended our analysis with the 2018 population: Any juveniles released after that may not yet have had time to return as adults, so that was the most recent population for which data was reliable.

We compared survival rates to benchmarks established by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council. In 2003, the council set a goal of 4%, on average, of all juvenile salmon who headed for the ocean would return to fresh water as adults, although it allowed for a range of between 2% and 6% annually. According to the council, these rates should be sufficient to ensure the recovery of the salmon species that are listed as endangered and to help reach the council’s goal of 5 million total salmon and steelhead returning to the Columbia and its tributaries each year. We used this approach for a couple key reasons. While individual hatcheries assess their programs using a variety of measures, we found that these assessments aren’t standardized and very few people are looking at the overall success of the hatchery system; the 4% benchmark allows us to look at the health of the system as a whole. We also listened to the advice of experts in looking at the data across multiple years because the results from any given year are too volatile to be meaningful.

In 2008-2013, only two of the eight populations we examined had average returns exceeding 4%: mid-Columbia coho and Snake River fall Chinook. In 2014-2018, none of the populations had average returns exceeding 4%. For the statistically minded, some further notes: To characterize the uncertainty in average survival rates for the two time periods, we ran bootstrapping experiments on the data using 1,000 trials within each time period to calculate 95th percentile confidence intervals around the bootstrap mean. The confidence intervals for three additional populations (Snake River spring/summer Chinook, upper Columbia River summer/fall Chinook and upper Columbia River steelhead) included the 4% recovery goal between 2008 and 2013. Between 2014 and 2018, the confidence interval for one population, the mid-Columbia coho, included the 4% minimum threshold.

It is important to note that fish biologists evaluate salmon and trout using a variety of performance indicators and metrics, with ocean survival being only one of them. Other metrics include the total number of juvenile fish released by hatcheries, the total number of adult fish returning to fresh water, the proportion of adult returns that started as hatchery juveniles, the state of local habitats, and even fish genetics. However, many of these measures are complex and difficult to compare across a variety of fish management practices, geographies and fish populations. By contrast, estimates of survival are readily available and offer a relatively holistic picture of how a population is doing. They also allow us to see the return on investment of the resources that have been allocated to hatcheries programs—a crucial measure given the limited amount of money available for this effort.

This estimate of ocean survival has some caveats. Only a portion of the salmon released each year are tagged. Furthermore, only a fraction of juvenile salmon survive the journey from release sites far upstream of Bonneville to the dam, and not all adult salmon that make it to Bonneville on the return trip will survive the full freshwater journey back through the hydropower system. That means the estimates drawn from these numbers are generous—the highest that they’ll be on the journey upriver. Nevertheless, these ratios of adult to juvenile tag detection can be considered an index that reflects the trends in populations that can be compared across species, migration patterns and release sites.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Tony Schick is a reporter with Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica, based in Portland, Oregon.

Irena Hwang is a data reporter with ProPublica in Atlanta, Georgia.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And now it’s time to check in on “The State of Science”–

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA News–

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

JOHN DANKOSKY: –local science stories of national significance. Over the past two decades, the federal government has funneled over $2 billion into salmon hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest. And although hatcheries in this region have been around for over two centuries, they’ve never really been able to replenish the wild salmon population as they were originally designed to do.

Despite more salmon being released into the Pacific Ocean than ever, fewer salmon are surviving. And this has had a profound impact on Native tribes who live along the Columbia River. They were promised access to fishing on their ancestral lands and now rely upon the troubled hatchery system.

This is the focus of an investigation by ProPublica’s local reporting network in partnership with Oregon Public Broadcasting. Joining me now to talk about their reporting is Tony Schick, investigative and data reporter with Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Science and Environmental Unit, and Irena Hwang, data reporter for ProPublica based in Atlanta. Tony and Irena, welcome to Science Friday. Thanks so much for being here.

TONY SCHICK: And thank you so much for having us.

IRENA HWANG: It’s great to be here.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So Tony, I’ll start with you and just ask how exactly we got here. When and why were salmon hatcheries developed in the Pacific Northwest to start with?

TONY SCHICK: The hatchery idea started back in the late 1800s when salmon were first getting depleted. Spencer Baird, who was a fisheries scientist and kind of the founder of NOAA Fisheries as it is today had this idea that we could hatch fish in huge numbers and release them into the rivers, and that would kind of bypass our need to limit our fishing or regulate it in any way.

The early hatcheries didn’t really have any evidence that they were successful in that. And then the idea of hatcheries kind of faded away in the Depression era. And then after World War II, when it was time to industrialize the Columbia River and the Snake River system, then proponents of that needed some way to offset the damage to salmon runs. And hatcheries were the only idea that they had, or the only solution they had. Then that is when the proliferation of hatcheries really started. That system is largely in place today.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Irena, you combed through hundreds of public records from these salmon hatcheries. Explain to us how big this problem is. How many salmon released into the ocean actually survive?

IRENA HWANG: So to get to that answer, first, I just want to establish that there’s tons of information out there. Hatcheries and federal agencies are employing highly-trained fish biologists who put out these reports and management plans that are, like, tens or even hundreds of pages long. Using that data, we did an analysis. And we reported trends and survival over the past decade or so.

And because salmon runs can vary significantly from year to year, the number of adult salmon that are migrating back, we wanted to see how good hatchery salmon survival has been, but also how bad it’s been. And we found that in the best case, only two out of eight vulnerable populations in the Columbia River basin exceeded a 4% survival rate. And that’s a rate that a federal agency in the 2000s established as necessary for a population to recover.

And in contrast, though, the most recent years of complete data for fish released between 2014 to 2018 showed that none of the eight populations exceeded 8% survival. One was really dismal. It was as low as 0.5%.

And I also just want to add that this is consistent with federal estimates. As of 2020, all hatcheries in the Columbia River basin area were producing nearly 150 million juvenile fish. But they were seeing only about 1.5 million return to fresh water. And you know, that 1.5 million, that’s about a 1% return rate.

That’s been estimated to be less than 10% of historical runs. Estimates are that in the mid-1800s, there were anywhere between 5 to 16 million adult salmon coming back. And we are clearly nowhere near that.

JOHN DANKOSKY: That is a big, a big change. So what do we know about why so few salmon are returning? I mean, what is it about salmon who started their life in hatcheries that makes them less likely to survive?

IRENA HWANG: Like any conversation with a bunch of scientists, I think it boils down to, it depends. But there was a fair bit of consensus in this case. The problem, though, is that the ocean is where most attrition happens. And it turns out that we really can’t know a whole lot about what exactly happens to fish in the ocean.

And it’s not only that– one NOAA scientist told me, quote, “The ocean’s been pretty weird,” end quote, in recent years. There’s something called The Blob– that’s a capital T, capital B– that scientists have been keeping an eye on. It’s a mass of warm water. It’s linked to changes in the climate and ocean ecosystem. Marine heatwaves have been occurring more frequently. And it is known that warm waters are bad for certain species of salmon.

And so yeah, it’s really complicated. But there are some clues. I came across a 2016 paper that showed that the hatchery environment, this artificial environment we’ve created, is really shaping salmon at a genetic level. Crowding them into tanks means that hatchery salmon genes are changing. Certain genes like those involved in wound repair, immunity, and metabolism are actually more active, but these genes aren’t necessarily the traits that wild salmon need to survive in a changing environment.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Tony, another factor that we mentioned at the top is that there are many Indigenous people who live along the Columbia River whose culture and livelihoods depend on these salmon hatcheries. What can you tell us about this and how these Indigenous communities came to be so involved in the salmon hatchery business?

TONY SCHICK: It wasn’t always that way. In fact, the early efforts at hatcheries, tribes were largely shut out of that even though they have depended on salmon and coexisted with salmon for thousands of years. And it wasn’t until tribes fought through legal battles to establish their role as co-managers of the river and started getting federal funding to run their own hatcheries that they started to take a more active role in these hatcheries and have used these hatcheries as a way to try and rebuild some of these runs. The tribes see this as kind of their only tool for putting fish back in the rivers.

JOHN DANKOSKY: But that’s what makes this so complicated, of course, is it may be their only tool, but it’s a tool that it seems isn’t working. In your research, is there any way to fix this?

TONY SCHICK: That is what makes it this kind of conundrum. And there are indications that this can be done better. And in fact, tribes have been at the forefront of pushing for that. They’ve been rearing fish in different ways to try and preserve more of that wildness. Instead of concrete pens, they will use ponds, more natural environments, to try and acclimate these fish to the rivers. Even these better ways of rearing fish are not a panacea. The complicating factors harming wild fish need to be addressed if you’re going to recover salmon populations.

JOHN DANKOSKY: It’s quite a piece of reporting and a very important story for the region. I’d like to thank Tony Schick, investigative and data reporter in Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Science and Environmental Unit, and Irena Hwang, a data reporter for ProPublica based in Atlanta. Thank you both so much for your time.

TONY SCHICK: Thank you.

IRENA HWANG: Thank you.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And if you’d like to read Tony and Irena’s full story, go to sciencefriday.com/salmon.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.