So You Think You Know About Sex

12:48 minutes

When it comes to sex, there’s really no such thing as normal. What was once considered taboo, sometimes goes mainstream. And some things considered new have been around as long as sex itself, like birth control, abortion, and sexually transmitted infections.

When it comes to sex, there’s really no such thing as normal. What was once considered taboo, sometimes goes mainstream. And some things considered new have been around as long as sex itself, like birth control, abortion, and sexually transmitted infections.

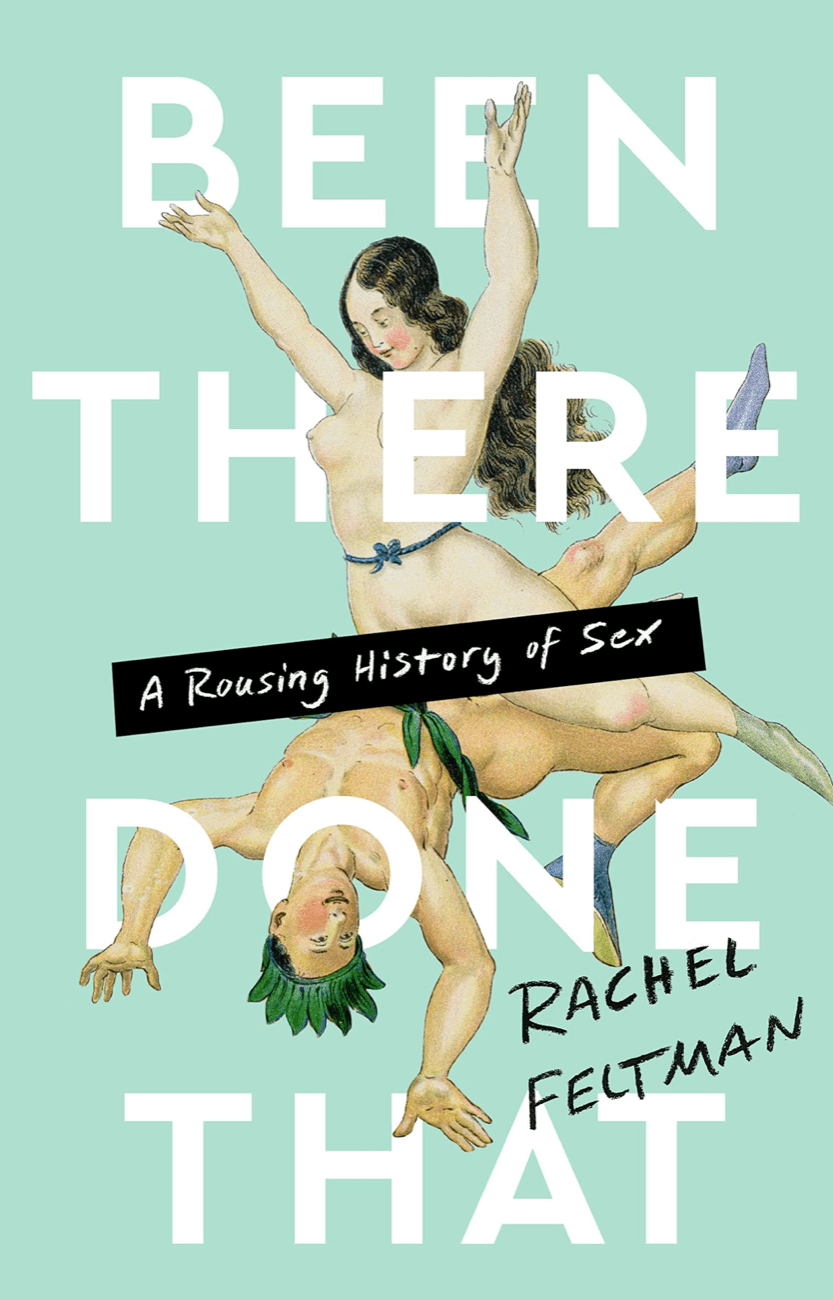

All that and more is contained in the new book, Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex, by Rachel Feltman, executive editor of Popular Science, based in New York City.

Radio producer Shoshannah Buxbaum talks with author Rachel Feltman about queer animals, crocodile dung contraception, ancient STIs, what led to the United States’ original abortion ban, and more.

Read an excerpt of Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex by Rachel Feltman.

This is a continuation of Science Friday’s coverage of the science behind reproductive health.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Rachel Feltman is a freelance science communicator who hosts “The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week” for Popular Science, where she served as Executive Editor until 2022. She’s also the host of Scientific American’s show “Science Quickly.” Her debut book Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex is on sale now.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. When it comes to sex, is there really any such thing as normal? I mean, what was once considered taboo can go mainstream. And much of what we consider recent developments and reproductive health care, like birth control and abortion, well they’ve been around, been happening in some form or another for thousands of years.

All that and more is contained in a new book called Been There, Done That, A Rousing History of Sex. It’s by Rachel Feltman, friend of the show, and executive editor of Popular Science based in New York City. We thought that as part of our continuing coverage of the science of reproductive health, this book would offer some good, historical footing taking us back in time. So we assigned our time traveler SciFri’s Shoshannah Buxbaum to speak with Rachel Feltman about her new book, and she joins us now. Hi, Shoshannah.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Hi, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Now I understand this book is chock full of fascinating animal facts. So what can gay penguins help us understand about human sexuality?

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Yeah. So you’ve probably heard about the numerous famous now gay penguin couples at zoos around the world. And it sure seems like a pretty recent phenomenon. It turns out that scientists and naturalists have actually been observing gay animal behavior for at least a century. Actually, probably longer.

IRA FLATOW: Really?

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Yeah. But as Rachel Feltman told me, there’s a long history of projecting sexual norms of the time, however misguided, onto animals.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Throughout recent history and the natural sciences, you see the researchers inherent biases really coloring what questions they even ask. Naturalists observe either just really voracious or violent sexual behavior among animals or same sex sexual interaction and just refuse to write it down because they’re, like, that must be an aberration for the species. There’s no way that can be common, normal relevant. And so they would leave it out.

A lot of what we think of as normal is really based on what researchers were even comfortable talking about. And, in the 1800s, I can tell you that was not male penguins having sex with each other. That was definitely not a thing they were comfortable talking about.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: One of the other examples in your book that I just have to bring up, I can’t do this interview without talking about it, is the three goose relationship that you talk about in the book. Tell me a little bit about this pretty actually common arrangement of how geese raise their young.

RACHEL FELTMAN: So a while back in New Zealand, there was this goose known as Thomas. And he took up with this injured female black swan who people called Henrietta. This was around 1990. And 18 years later, according to the BBC, another female black swan showed up, and then she laid eggs.

It turned out they were Henrietta’s eggs because Henrietta was actually a Henry. And Thomas, this goose, was a gay icon, and no one had known this whole time. The throuple eventually settled into a rhythm and then Thomas took on a parental role as Henry went on to have 68 children.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Oh my gosh. 68?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Impressive.

RACHEL FELTMAN: And according to research on black swans, at least for them, this setup would have actually probably felt pretty normal interspecies aspect of it aside. Black swans are known to have a few different potential setups for meeting and parenting. But actually, according to at least some research, the most stable pairing is when there are two males and a female and they all stay together. This is a family structure that works from an evolutionary standpoint.

We’re taught your biological imperative is to make babies. And so people see sexual orientations that don’t involve procreative sex as being somehow a strange exception to that. But we do see examples in the animal kingdom of situations where they’re being parents who aren’t physically reproducing themselves as an evolutionary benefit.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: And so now any conversation about sex has to, unfortunately, get into some of the downsides. And it turns out, I learned, that romances between Neanderthals and early human ancestors actually led to them swapping STIs, sexually transmitted infections. What happened?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Well, what happened is that STIs are supernatural and normal and have existed for much longer than humans have. And HPV and HSV, which is herpes, we did have some trading back and forth. HPV, we got that from Neanderthals, and we gave them HSV. There were some really unfortunate headlines a couple of years ago about how we killed Neanderthals with herpes. That is not true.

So humans are unusual in that we have two strains of HSV, herpes simplex virus. We have HSV 1 and HSV 2 are what’s known as oral and genital herpes. Extremely similar and it’s because one is the version that we evolved with in a more original sense, which gives us cold sores usually.

And then the other one is one that we caught from some other primate relative. Probably not through sex. It was probably more like one relative ate a certain primate, and then maybe we had sex with the other primate. It’s a twisted web we wove as early humans.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: So I want to pivot a little bit to a topic that gets a lot of conversation. That’s contraception, and a lot of people think of it as a modern invention. But preventing pregnancy, just like STIs, are as old as sex itself.

And one particularly eye opening example that you write about in the book is that ancient Egyptians used a mixture of crocodile dung as a contraceptive device. How exactly did that work? And do we know if it worked as a contraceptive?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Well, for reasons that are probably obvious, no one has, to my knowledge, tested this. This is pure speculation in terms of how well it would have worked. But it does make sense because the crocodile dung would have helped create a physical barrier against the cervix. And it also would have helped change the pH of the vagina, which we know is a really valid method of birth control. In fact, one of the most recently FDA approved birth control products is a gel called Phexxi that changes the pH so that it’s not hospitable to sperm.

And the crocodile dung was very similar. They often used honey as well, which we now know has potent antimicrobial properties, which is great if you’re putting poop anywhere near your vagina, which is not something you should do ever just to be clear. And we see that combination of a cervical barrier plus a pH influencer again and again through history.

There are sponges soaked with vinegar in the Talmud. You see ghee being used by women in India thousands of years ago. People have been trying not to have babies when they have sex for a very, very long time.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Yeah. And similarly to contraception, abortion is also very much not new as much as we tend to think of it as new and access to abortion in the US has been on a lot of people’s minds in these past several weeks. And especially the impacts of a reversal of Roe v Wade, which was what made abortion legal in the US to begin with, and people are pretty familiar with that.

But the history of how abortion was banned in the first place in the US is not as widely known. And in the book you talk about the history a little bit. So how did Horatio Robinson Storer and the creation of the American Medical Association lead to an abortion ban in the mid 1800s?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. So what’s really interesting is, and pretty intuitive once you think about it, is that when you look back in ancient history, there isn’t a lot of distinction morally or practically between methods of birth control and abortifacients because before we had any insight into the mechanisms of gestation, the line was a lot blurrier between stuff you took to end an early pregnancy and stuff you took to not get pregnant and stuff you took in case you might be just a little bit pregnant. And even up into the 19th century, you see abortion, and especially early abortion, as really being seen as a personal issue. It’s not to say that no one ever opposed it. Certainly there were religious institutions that opposed it and not just in recent history.

But nobody was making laws around it. We see records showing that people terminated pregnancies. And Horatio Robinson Storer was very much opposed to abortion. Where things got tricky is that he was one of the first true OB/GYNs and the American Medical Association was really in its infancy. And, in fact, the idea of being a doctor in the modern sense was pretty new.

And the American Medical Association was working on ways to medicalize medicine. Because for all of human history, there may have been people who were especially respected or known for the medical care they could offer. And there were also people performing abortions, and a lot of those people were midwives and other female health care providers.

So it’s now pretty clear that whatever Horatio Robinson Storer believed, the American Medical Association supported his crusade against abortion because it was a way to distinguish themselves from midwives and other female providers of health care because abortion became this evil, dangerous, unseemly thing that women in back alleys would do. Even though these were the women who had been taking care of other women’s health for–

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Right.

RACHEL FELTMAN: –hundreds or thousands of years. And that stood in contrast to OB/GYNs who were these white men who had been educated and who would take care of you in a medical setting. The American Medical Association came out hard against abortion. They really laid the groundwork for abortion becoming illegal.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: What can taking a look through our sexual history, not our personal ones, our collective ones, help us understand about how we think about sex today?

RACHEL FELTMAN: The main takeaway of my book is that we get so embarrassed about sex. We feel so much shame around it. We’re really taught to believe that there is stuff that’s normal and stuff that’s not. And it’s all very much based on very recent cultural hangups. And no matter who you’re attracted to or what you’re into or what your goals are when you have sex, you are really not alone, and humans have definitely done that thing.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: And I think that’s a perfect place to end. So, Rachel, thank you so much for being on Science Friday and talking about your book.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thank you so much for having me.

SHOSHANNAH BUXBAUM: Rachael Feltman is the author of Been There, Done That A Rousing History of Sex. She’s also the executive editor of Popular Science based in New York City. Ira.

IRA FLATOW: SciFri’s Shoshannah Buxbaum. If you want to read an excerpt of the book on our website, go to sciencefriday.com/sexhistory. sciencefriday.com/sexhistory.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.