Don’t Panic About Monkeypox Yet, Says Expert

6:54 minutes

Editorial note: The World Health Organization announced in June that they wanted to rename monkeypox, citing racism and other stigma attached to the current name. Pending that decision, “monkeypox” is how Science Friday will refer to the disease in the meantime.

This week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced it was investigating five cases of purported monkeypox that had been found in the United States. This is a disease that’s endemic to parts of central and west Africa, and is rarely seen outside of those regions. The small number of cases here in the U.S is unusual.

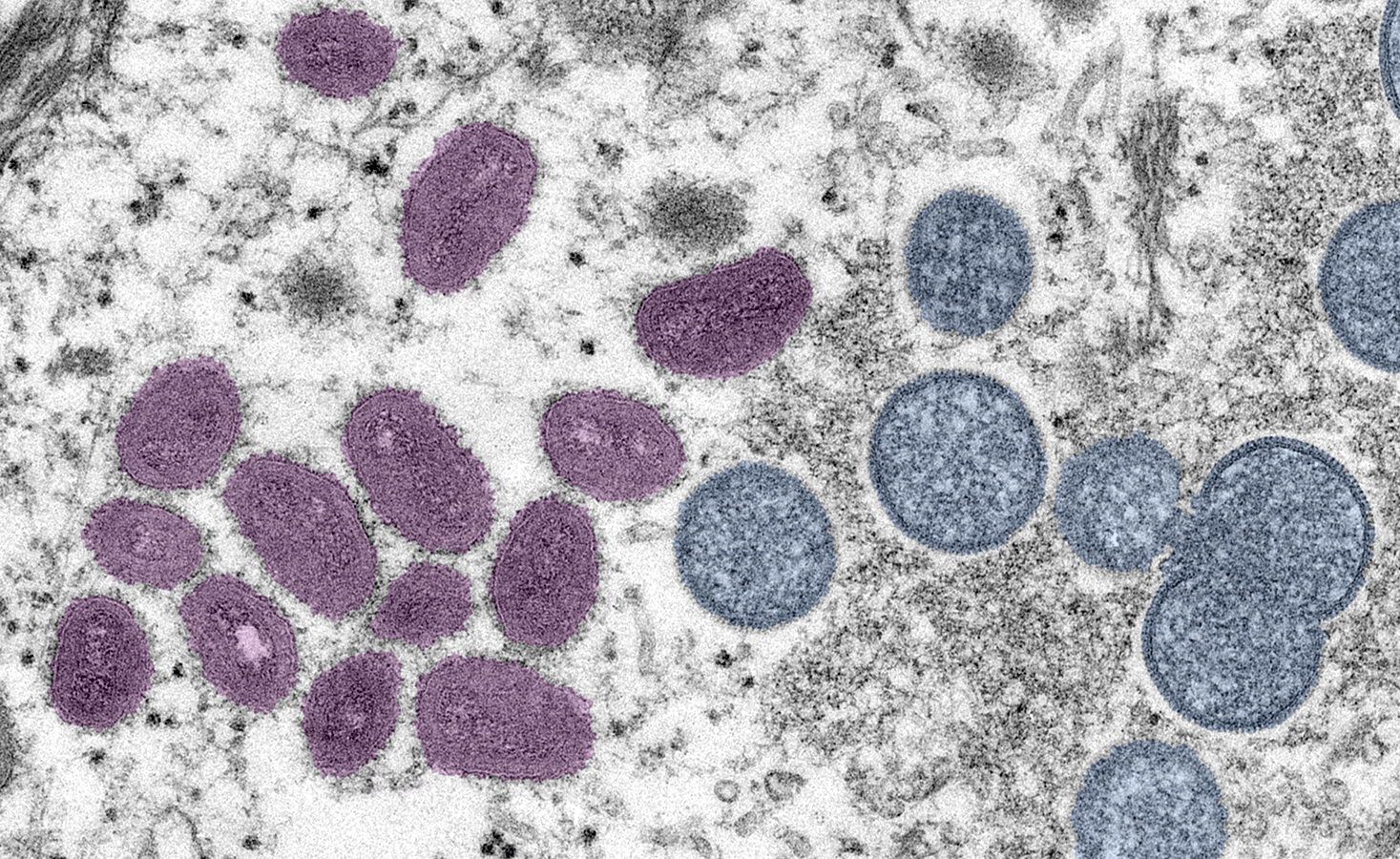

Monkeypox can spread from person to person through skin-to-skin contact or respiratory droplets. Its most striking symptom is an active rash and lesions in the mouth, though can also present as flu-like and include fever, headache, and soreness.

As we’re still grappling with our COVID world, many people are concerned about this new illness. Dr. Anne Rimoin, professor of epidemiology at UCLA’s School of Public Health in Los Angeles, California, joins guest host John Dankosky to explain what’s going on with this wave.

We should be concerned, but not alarmed. Having a virus spread into new populations is something that public health officials must keep an eye on. Monkeypox can be a substantial disease in people who are immunocompromised, but can also present in milder forms.

People vaccinated against smallpox are likely protected against monkeypox. Smallpox vaccines were phased out in the U.S. in the early 1972, when the disease was eradicated in the country. Monkeypox is a cousin of smallpox, and data shows that the smallpox vaccine does reduce severity of monkeypox, even if the inoculation happened decades ago.

Public health workers need to be vigilant. While spread of monkeypox is unlikely unless close contact is happening, health care workers should be looking out for unusual rashes in patients. “If the current COVID-19 pandemic has not driven that home, we need to have excellent disease surveillance, we need to have the capacity to be able to do case investigations, contact tracing, and really get to the bottom of what’s happening,” Rimoin said.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Anne Rimoin is an epidemiologist studying monkeypox at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health in Los Angeles, California.

JOHN DANKOSKY: We’re going to shift gears now to another story that’s been in the news all week– monkeypox. This is a disease that’s endemic to parts of Central and West Africa and is rarely seen outside of those regions. The CDC is investigating a small number of cases here in the US, which is unusual. Monkeypox can spread from person to person through skin-to-skin contact or respiratory droplets.

As we’re still grappling with our COVID world, many people are concerned about this new illness. So to help us understand monkeypox and how concerned we should be is someone who has studied it for decades, Dr. Anne Rimoin, a professor of epidemiology at the UCLA School of Public Health in Los Angeles, California. Welcome to Science Friday. Thanks so much for being with us.

ANNE RIMOIN: It’s nice to be here. Thank you for having me.

JOHN DANKOSKY: As I said, you’ve studied monkeypox for decades now. What is your level of concern about this increase in cases.

ANNE RIMOIN: I think it’s important to be concerned, because we’re seeing a virus spread into populations and in geographic regions where we’ve never seen it. We’re seeing new patterns. When you see new patterns of a disease, that’s when you need to be concerned. But I think the issue of concern should not be conflated with alarm. And that’s very important to remember.

JOHN DANKOSKY: How serious a disease is this?

ANNE RIMOIN: Well, monkeypox can be a very substantial disease. But it also can present in much milder forms as well. You know, I’ve been working in the Democratic Republic of Congo for two decades. And the monkeypox clade that is seen there, the version of it that we see in DRC, is much more severe than the West African clade.

And that West African clade is what we’re seeing associated with these clusters of cases. And that is a much milder form of disease. But that’s not to say it can’t be serious in individuals, in particular individuals who may be immunocompromised.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So do you know why these cases are on the rise right now?

ANNE RIMOIN: Well, one of the major drivers of these importations of monkeypox from Africa is that we had this amazing achievement of the eradication of smallpox. And when smallpox was eradicated, we ceased vaccinating the vast majority of the world. So as time has gone on, the world no longer has any immunity to smallpox or any other related viruses. Monkeypox is a cousin of smallpox.

And therefore, when you have a population that has no immunity to a virus and is exposed to a virus, we’re likely to see spread. We’ve seen increasing cases in Africa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in Nigeria. And so it makes sense, with increased travel and trade, eventually we’re going to see importations of these cases of monkeypox that are occurring on the ground in these endemic countries. And when somebody else comes in contact with a person who has monkeypox, it’s a perfect opportunity for spread.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Does the smallpox vaccine protect against monkeypox?

ANNE RIMOIN: The smallpox vaccine does provide protection against monkeypox. My early work on monkeypox documented a large rise in the incidence of monkeypox 30 years after cessation of smallpox vaccine. And we felt that one of the major drivers of this was this rising proportion of the population that had no immunity. And we saw very few cases in people that had been vaccinated.

Now, there’s a question of how long the vaccine is going to hold out. And if you have a significant exposure, you still very possibly could become infected. But it’s very probable that the vaccine would provide some protection even in terms of reducing the severity of disease.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So we haven’t been vaccinating against smallpox in the US for about 50 years or so. There’s a sense that with climate change, deforestation, closer proximity to wildlife, there are chances for more diseases like this– and certainly global travel– to jump from animals to people, to jump from one part of the world to another part of the world. Should we be getting vaccinated against smallpox and other poxes?

ANNE RIMOIN: I think at this point, that’s not really something that we need to be concerned about or have on the table in terms of discussion. Pox viruses that we’re concerned about as a threat to humans are generally only endemic in places like sub-Saharan Africa. And even there, the disease is still reasonably rare, rare enough that these governments are not really considering doing any kind of mass vaccination.

The threat is reasonably low. The risk is reasonably low, in general. That said, I do think that when you see increase in cases, we do need to consider options of using vaccine for people who have been exposed, people who are at high risk of exposure. But we’re always weighing the cost benefit and also the availability of this kind of vaccine. And so I think it’s just important that this is something that will be considered for certain populations at risk, but it’s certainly not something that is going to be needed on a mass population level.

JOHN DANKOSKY: When you see news coverage of lesions and sores and people worried about monkeypox coming to the United States and to North America, what do you tell people? What are you looking for, and what is your thought as you see this coverage?

ANNE RIMOIN: Well, I think that there are different levels of concern for different groups of people. Now, I think we have to differentiate the concern for a health care worker, for example. A health care worker who may come in contact with cases may be more concerned and be more cautious, be on the lookout for unusual rash or a history of travel to a monkeypox-endemic area in the last month. And I think that that’s a different category.

Now, when we think about this on a global level, or on a policy level, I think it’s really important to remember that an infection anywhere is potentially an infection anywhere. And if the current COVID-19 pandemic has not driven that home, I think that these clusters of monkeypox cases really should, that we need to have excellent disease surveillance. We need to have the capacity to be able to do case investigations, contact tracing, and really get to the bottom of what’s happening. This is certainly a situation that requires attention, focused intervention, and a real evaluation of what needs to be done in terms of preventing pandemics before they start.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Dr. Anne Rimoin is professor of epidemiology at the UCLA School of Public Health in Los Angeles, California. Thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate it.

ANNE RIMOIN: It’s my pleasure.

JOHN DANKOSKY: We’ve got to take a break. When we come back, parents of newborns are worried about the baby formula shortage. We’ll talk about why formula is such an important source of nutrition for millions of babies.

This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.