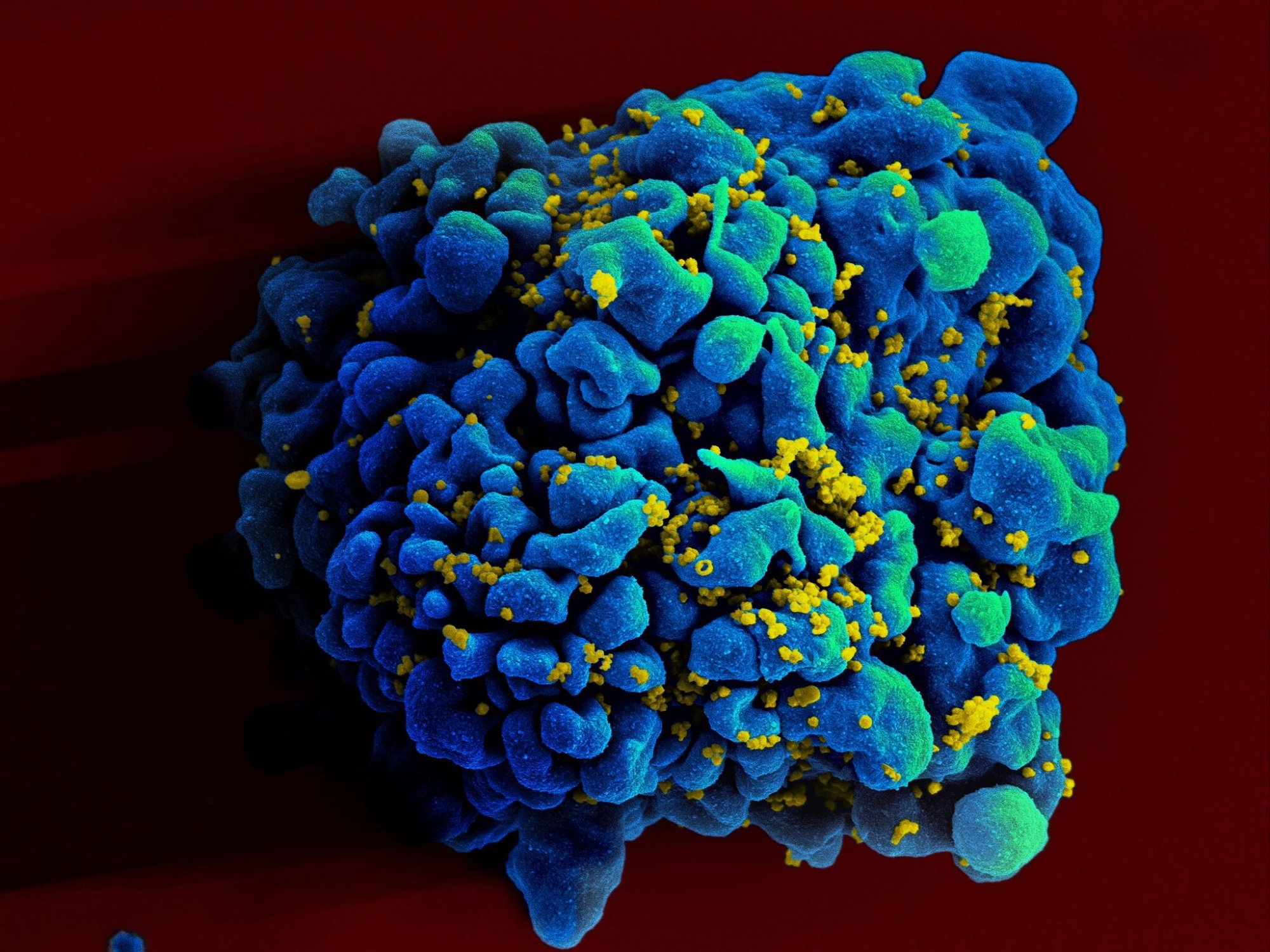

Third Person Cured From HIV, Thanks To Umbilical Cord Stem Cells

12:17 minutes

The third person ever, and the first woman, has been cured of the HIV virus, thanks to a stem cell transplant using umbilical cord blood. While the invasive, risky bone marrow transplant process may not prove the answer for large numbers of people, the use of cord blood may open up pathways to new treatment options for a wider variety of people than the adult stem cells used to cure the two previous patients.

Vox staff writer Umair Irfan explains why. Plus how President Biden is using executive orders for decarbonizing new parts of the economy, new research on the climate origins of the mega-drought in the American West, a prediction for even more rapidly rising sea levels from NOAA, and how orangutans—some of them at least—might be able to use tools.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Umair Irfan is a senior correspondent at Vox, based in Washington, D.C.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, we’ll talk about a major advance in nuclear fusion, and Dr. David Satcher recalls his lifelong quest for health equity. But first, a leukemia patient has become the third person ever to be cured of the HIV virus– and the first woman– and it’s all thanks to a transplant of stem cells from umbilical cord blood.

In contrast, the previous two patients were cured with transplants of adult stem cells. What does this mean for the potential of others with HIV to be cured? Vox staff writer Umair Irfan is here with more. Welcome back to Science Friday.

UMAIR IRFAN: Hi, Ira, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. You know, this sounds like such good news– another person cured of HIV. How is this woman’s case different from the other two people we’ve seen cured?

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah, you know, this is definitely good news and we should dwell on that. But this woman was in a fairly unique situation. Apoorva Mandavilli at the New York Times wrote about this and she explained that this woman, yes, had leukemia and was being treated for that, but also she was being treated with umbilical cord blood. And this is a source of stem cells but these stem cells tend to be a little bit more robust.

And one of the other factors that was significant here is that this woman was of mixed race. And so typically when you do these kinds of transplants with bone marrow, you want to try to match the donor and the recipient as closely as possible. But with cord blood, it seems to be that you actually have a little bit more flexibility. And this could potentially be something that you can use in a larger group of people than we previously could with other treatments.

But as you noted, she had leukemia. She was already being treated for another blood disorder. So it’s not like this is a therapy that we could use for other HIV patients. But doctors say that this could potentially chalk out a path for a more generalized treatment.

IRA FLATOW: And when we say people are cured, that means they’ve survived longer than five years or more?

UMAIR IRFAN: Well, what it means is that they think that the virus is no longer present in their bodies. HIV over the years has become a more treatable illness with antiretroviral drugs and it’s basically become a chronic condition. But the virus itself is very insidious. It can actually integrate into the host genome. And so even if you knock out all the virus particles, it can still come back in the future.

But in this case, it seems like these patients are no longer having even that presence of HIV– that it’s no longer present in their systems at all. But that requires basically resetting how their body produces blood cells with these bone marrow transplants. And so it’s a very invasive procedure.

The past two patients who were treated with us– the two men– they both had some very severe complications. This woman who was recently treated, fortunately, seems to be in better shape. She left the hospital after about 17 days and seems to be faring a little bit better. And that may be because of the source of stem cells being cord blood.

IRA FLATOW: So you mentioned the invasiveness of bone marrow transplants. Everyone can’t do this, right? So can we learn something from these successful cures that might translate to something more accessible in the future?

UMAIR IRFAN: I mean, that’s certainly the hope that eventually we could come up with a way that people who don’t have leukemia can be treated for– that have HIV. But right now, that’s still is something that’s still a little bit far off. But scientists are definitely excited. It is good news to have one other person cured of a disease that was previously thought uncurable.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have some good news for news for a change. Your next story though goes in the opposite direction– so bad news. The big drought in the American West right now it turns out is a pretty bad one.

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah, that’s right. You know, anybody who’s lived in the Western United States doesn’t need a reminder of this, but water has been in scarce supply. But a couple of recent studies put it into context. And so Gabrielle Cannon at The Guardian wrote about a study that looked at the history of drought over the past two millennia, and the researchers there reported that this is now the driest spell that we’ve seen in at least 1,200 years. And that’s referring to the period between 2000 and 2018.

And of course, we’re already seeing the consequences of that– not just low water levels but also extreme heat. Water in the landscape acts as like a natural air conditioner and we’ve seen a lot of heat waves in the Western US. And this is also a major contributor to wildfire risk.

And one other interesting aspect about the study is they also calculated how much humans have made this worse. And so there’s been this advance in this subfield of climate science called attribution, and in this case, they found that about 42% of this drought was made more severe due to human production of greenhouse gases.

IRA FLATOW: So it could get even worse then?

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah, that’s the idea is that, if we continue putting more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, some of these trends will continue to be exacerbated. But drought’s a little bit tricky because we know that some parts of the world are going to get drier, but some parts are actually going to get wetter. Because as air gets warmer, it can hold on to more moisture. And so it’s not necessarily a straightforward path that it will necessarily lead to more drought, but the there are a lot of complicated factors at play. And in some cases, we could actually see this sort of whiplash between extreme rainfall and extreme drought.

IRA FLATOW: Well, you’ve brought me to my next subject. Nice segue. From famine to flood because we’re also seeing a more rapid sea level rise on the East Coast and in the Gulf of the US. 100 years worth in just 30 years?

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah. Seth Borenstein at The Associated Press wrote about this NOAA study that examined, again, the history and the future of sea level rise. And they found that, yeah, we’ll probably see the whole past 100 years worth of sea level rise over the next 30 years. So this is about 10 to 12 inches around US coastlines. But some parts are actually going to see a little bit higher sea level rise than others. So the Gulf Coast may see sea level rise as high as 1.5 feet.

And there are a few different reasons for that. Water does like to seek its own level but the planet is round, and there are also ocean currents. And so there are parts of the country where you will see higher water levels than others. You also have ground subsidence and that, of course, has huge consequences. About 40% of the US population lives in a coastal county.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, we’re also talking about not just big rainfall events– you have the hurricanes, and now you have the sea level rise. It’s going to be pretty wet.

UMAIR IRFAN: Right. And so when you have these events that normally happen– like sea level rise– like hurricanes pushing water inland– those events are going to be more severe. But it also means that we’ll see more nuisance flooding– like flooding on clear days with blue skies– the king tide flooding that you can see in some parts of the United States already, in places like Miami. That’s actually going to be more severe over the coming decades.

IRA FLATOW: And of course, that’s going to be very expensive because there’s going to have to be a huge infrastructure ready for this kind of sea level rise and that doesn’t exist yet.

UMAIR IRFAN: That’s right. Parts of the country are trying to build things like seawalls and channels to help redirect this rising water, but it’s a moving target. As it’s accelerating, as this water is moving up faster, cities and coastal regions are trying to adapt and are kind of scrambling to try to make sure that they can mitigate these losses. And in some cases, they have to retreat. It’s not going to be worth preserving them at a certain point. It’s going to be too costly.

IRA FLATOW: And 30 years is not a lot of time to adapt to this kind of thing.

UMAIR IRFAN: No, it’s not.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: What’s interesting about both of these studies– this new mega-drought and the rapid sea level rise– this is sort of a recalibration of what we can expect from extreme climate change, isn’t it? It feels like more than just the usual bad news.

UMAIR IRFAN: Right. The scientists start probing these mechanisms and looking at them in more detail. They keep finding unexpected ways in which they are interacting. And so we generally do see that, as scientists look at these things more closely, they find that things like sea level rise are happening at a faster pace than they expected, or that aridity and drought are more severe than they realized. And what that means is that, likely in the future, there may be more unexpected mechanisms that we don’t appreciate now that could make the situation worse.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Let’s talk about steps that can be taken. The president’s big climate bill fell flat last year but he’s back at the effort to decarbonize. But this time with executive orders. What’s he trying to do here?

UMAIR IRFAN: Right. Since the Build Back Better bill has been stalled in Congress, the White House is trying to look at ways that they can use their executive authorities– the things that are already granted to them under the Constitution– to try to get some climate change action underway. And the White House has already done that in several different ways with things like electric vehicles and federal procurement.

But this new executive order this week looks at the industrial sector. And this is something that’s kind of obscure from public view. These are businesses and industries that make the stuff we use to make stuff– you know, metals, concrete, and other kinds of building materials. And they account for about one third of US greenhouse gas emissions.

And so what President Biden wants to do is use the federal government’s purchasing power to make sure that the federal government buys materials that are produced with less carbon-intensive and in cleaner ways– hopefully sending a signal to the rest of the economy that this is a viable way to actually pursue construction projects and to pursue building materials. But there’s another couple investment areas in this as well. One thing that the White House is doing is they’re betting big on hydrogen. They’re calling for about $9 billion in investment on hydrogen fueling stations, but also ways to produce hydrogen in a clean way.

Right now, we get hydrogen fuel mainly from steam reforming methane, which has a carbon footprint. And so what they want to do is try to come up with ways to get hydrogen from water, using renewable energy. And one other interesting thing about this executive order is it’s also looking at trade as a lever. We’re trying to get other countries to clean up their act as well by putting limits on the kinds of metals that we import from other countries. So basically, we’re going to set a standard for metals and other materials that we import by saying that if you don’t adhere to our environmental rules in producing these materials, then we will either add a tariff or restrict their import into the country. And that’s a way to nudge other countries to do more on climate change as well.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, and this is typical of the government setting example using its big buying power to sort of turn that giant industrial ship in a different direction.

UMAIR IRFAN: Right. It’s kind of hard to overstate how big the US federal government is. The military alone is the single largest employer in the world. And so you have all these buildings, infrastructure, vehicles, and just by getting the federal government to set tight standards for itself, it becomes a big purchaser, and that can help lead to economies of scale. But then also, if the government can validate and show that this works and this is cost effective, then other businesses may want to step up and try to clean up their activities as well.

IRA FLATOW: That’ll be interesting to see how the hydrogen side plays out here. Is there a downside to using executive orders for climate change measures?

UMAIR IRFAN: Well, as we’ve seen between the administrations over the past couple of years, all it takes is another administration to come in and undo everything with an executive order. So this stuff is not set in stone, but what the Biden administration and the White House is hoping is that there’s enough inertia baked in that, if they can get these initiatives rolling, they’ll have enough benefits that they’ll be irreversible. And essentially, it will be much harder politically and feasibly to actually undo some of these changes.

IRA FLATOW: And one last story, really quick. Orangutans using axes? It sounds like the opening of the film 2001, A Space Odyssey.

UMAIR IRFAN: Yeah, that’s right. I read a piece in New Scientist about this by Michael Marshall. So a team of researchers, looking at orangutans at a zoo in Norway, found that they could actually use tools even without being instructed on how to do so. Now orangutans are a species that live in trees and so they don’t typically interact with stone tools on the ground. But these researchers found that if they gave them a box that was tied up with a string and a sharp rock, the orangutans figured out exactly how to use the rock to cut open the string and to get the fruit that was inside.

But the one shortcoming they had was they couldn’t quite coach the orangutans to make the tools in the first place. So that seems to be a little bit of a bridge too far. But it is interesting that they were able to show initiative in using these tools that they’ve not encountered before.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Umair.

UMAIR IRFAN: My pleasure. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Umair Irfan, staff writer at Vox. He joined us from Washington, DC.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.