These Beetles Go Boing

12:57 minutes

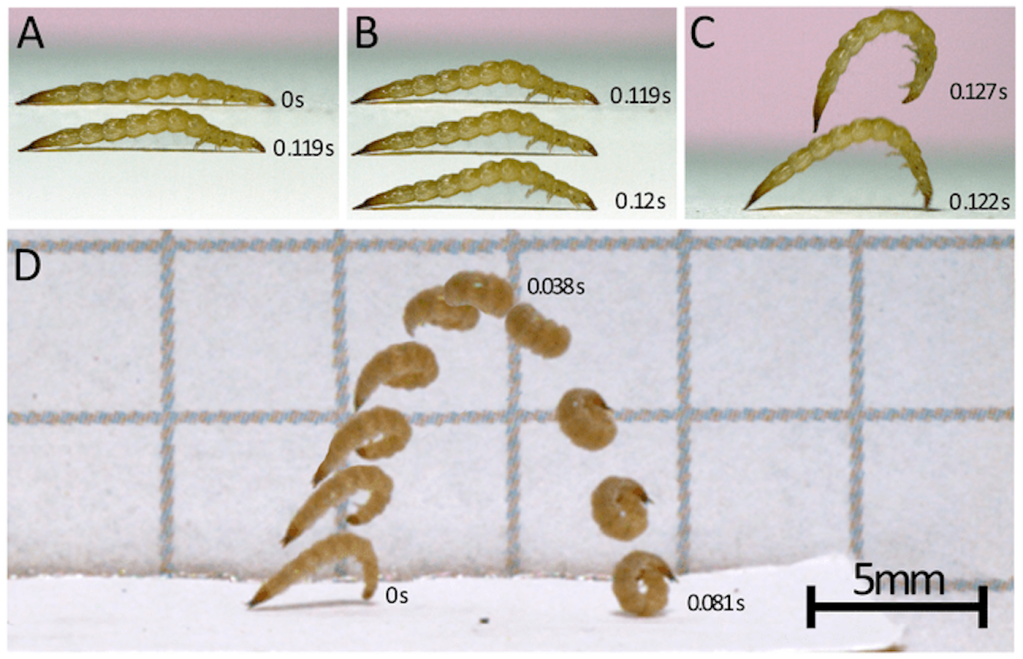

There are plenty of insect species that jump—leafhoppers, crickets, fleas, and more. Some use powerful legs to take to the air. Others, like the click beetle, rely on a latching mechanism built into their bodies to build up energy, then release it suddenly. But writing in the journal PLOS One this week, researchers report that they’ve spotted a species of lined flat bark beetle (Laemophloeus biguttatus) that uses a different method to jump—the beetle larvae dig into a surface with tiny claws, flex, and build up energy, before releasing it and flinging itself into the air in a tiny ring.

“It was really exciting to know that we had seen something possibly for the first time and definitely reported for the first time,” said Matt Bertone, an entomologist at NC State University and one of the authors of the report. The jumps themselves aren’t very impressive—only a few body lengths—but the discovery of a new mechanism that doesn’t rely on a specialized body part is intriguing. The authors aren’t quite sure why the larvae, which live under tree bark, have evolved the jumping behavior, but hypothesize that it may be to rapidly move when their bark habitat is disturbed.

Bertone joins Ira to talk about the unique form of locomotion, and where the researchers might look next for the behavior.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Matt Bertone is an entomologist and director of the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, North Carolina.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. If you’re a regular listener to our show, you know that we like to find unusual creatures, even charismatic ones. And lots of those are creepy crawly things or real jumpers. Think leaping leafhopper or a springy cricket. Well, this week, we found another one for your consideration– a common beetle that you can find in a dead tree on your lawn, whose larva are able to jump in a way that hadn’t been described before. This work was published this week in the journal PLOS One. Joining me now is Dr. Matt Bertone, an entomologist at NC State University and one of the authors of the report. Welcome to Science Friday.

MATT BERTONE: Oh, thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: OK, tell us about this beetle. What is it, and where does it live?

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, so it’s a little, fairly nondescript beetle. And what we described was the actual larval stage, behaviors of the larval stage. But this species is common throughout Eastern North America, fairly small, and kind of obscure typically, so people don’t usually see it. The adults are small brown beetles with a very flattened body and two spots on the body. And the larvae are just small worm-like critters that crawl around under the bark of dead trees.

IRA FLATOW: And you found this one actually on the bark on campus, right?

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, that’s correct. There was a standing dead oak tree that was developing some fungus on it right outside of our building. And of course, because I pass it every day, I had to just collect some insects from it, especially for the specimens and my photography. And that’s–

IRA FLATOW: This is what you do.

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, yeah, this is what I do, so regular day for me.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about what makes this beetle and the larva so different from other jumping insects.

MATT BERTONE: So, many adult insects jump. You think of crickets and grasshoppers. Even adult beetles, there are many species that jump. And they usually have large hind legs, and they just kind of launch off the surface. What this larva does, though, is very interesting. In fact, it builds up energy in its body and latches onto the ground with its claws. And as its body builds up energy, it releases those claws. And this causes the insect to somersault into the air a short distance.

IRA FLATOW: And there’s nothing weird about the claws then.

MATT BERTONE: Nope, they’re fairly typical larval claws. Nothing special really about them.

IRA FLATOW: Well, if they live under the bark, why do they need to be able to jump? They’re not going to be jumping any place under that bark, are they?

MATT BERTONE: Yes, so that’s a great question. And we’ve been trying to figure out exactly why. The logic will be that since it’s under bark, it doesn’t need to jump, of course. So part of what we thought was maybe this is some artifact of a behavior they do under the bark. There are other larvae that are known to wedge push, so they kind of bump up a little bit under the bark to give it more space to crawl under. But we didn’t think that was really the case. Why develop that behavior if you’re under bark most of the time?

Other beetles that have kind of jumping larvae often do that to escape predators or parasites. But we noticed that these larvae, you put them down on the ground, they crawl a little bit, and then they’d hop on their own. You wouldn’t have to kind of touch them or do anything to make them jump. So it came down to us thinking about their lifestyle.

And my ideas and our thoughts were that this source, rotting wood and trees that are standing with bark that’s kind of falling off, could easily expose these larvae. And they’re light-colored. They’re on a dark surface. They could easily be picked off by predators. So one of my hypotheses is that they do this to get away from their sites, either when exposed or just because they want to. And it’s more energy effective to do that than to crawl.

IRA FLATOW: Now you mentioned before that they’re not– how shall we say– great jumpers. And so the height of their jumping and their jumping ability, their talent for jumping is not what interests you, but it’s the way that they jump that interests you, right?

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, so they’re definitely not record setters. They’re definitely not even super impressive. They are when you see them with the naked eye because it’s fairly quick. But when we actually went to record the distance and the heights, they were not jumping very far, really. But beetle larvae jumping are really rare. And beetles are a huge group of insects. There are over 350,000 described species on Earth. And so you would think you would find it more commonly, but it’s actually fairly rare in beetles. And then the second aspect was the way they jumped using this latching mechanism with the ground is very unique.

IRA FLATOW: And they do this pretty quickly because I was watching a video of your colleagues showing us how they jump, and you had to use a really high speed camera to see the details.

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, so Dr. Adrian Smith at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences downtown in Raleigh, one of his specialties is filming high speed videos of insects. And so this was a great collaboration. So when you see the jump with the naked eye, it’s very quick. When we showed it at 3,500 frames per second, we could see the basics of it. But he actually went to a special lab to get filming of 60,000 frames per second, in which we were able to see even more details.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Now does it matter what surface they are on? If they have to use their claws to sort of set the spring in their body, right, does it matter that they’re on a slippery surface?

MATT BERTONE: So that’s actually one of the lines of evidence we used to show that this is actually a latching mechanism. Adrian did film some on Plexiglas and glass surfaces, and they were unable to jump. So that leads us to believe that they really do need something to latch on with their claws.

IRA FLATOW: Do you get the impression that this is a talent that, evolutionarily speaking, they had to develop a little bit later in their evolution because they just don’t have the jumping body style that the other big jumpers have?

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, this seems to be– I’m not sure when they developed it, but it does seem to be a fairly simplistic way to do it if you think about it because most insects have claws. And they’re crawling on the surface. They can grab down. So it really didn’t require any specialized anatomy that in many insects that do have those special organs to latch and jump, they didn’t have to evolve those.

IRA FLATOW: I kind of find it interesting that after the jump is finished, they sort of curl up into a little ring and then bounce around on as they land. It’s like a tire. It reminded me of a tire, right?

MATT BERTONE: Exactly, I love the little bounces when they hit the ground. I don’t know how they feel when they’re doing that. Luckily, they’re pretty light animals, and they can resist it. And yeah, it’s pretty erratic, their jumping. They don’t really aim somewhere. They’re not trying to get somewhere special, but we think that it helps kind of introduce different areas for them to explore.

IRA FLATOW: Do you have any feeling about what actually makes them jump– loud noises? Do you have to poke them? What’s the stimulus there?

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, so they seemed to just jump when they were kind of exposed out in the open, crawling around. That was what led us to believe that it wasn’t so much them directly responding to some kind of predator or parasite. You could grab them with the soft forceps or touch them with a paintbrush, and they’d crawl along and jump. But even if they were put out on the surface alone with no kind of stimulation like that, they would crawl around for a bit and then jump. And so that’s what we were able to observe with the specimens we had. But unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of live specimens to experiment with. So a lot of that stuff is still a mystery.

IRA FLATOW: And to bring that up, to take that one step further, I noticed that when you posted this behavior online, other folks had seen it, too, in their species.

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, that–

IRA FLATOW: So you found other comrades.

MATT BERTONE: That was one of the greatest things about this. Actually, in fact, it was really interesting. So we talk about these jumping larvae. Under the same bark with these larvae, there were also fly maggots. And many maggots are known to jump. And what they do is they latch their mouth parts onto their rear end and then stretch their body and then releasing that energy. So they use a body-to-body latch.

But at the end of a video that Adrian produced about those jumping maggots, he alluded to and showed a clip of this beetle larva jumping just as a teaser. And out of the blue, he got a message from a Japanese researcher, Takehiro Yoshida. And he is a world expert on this group of beetles. And because he collects them, he had noticed one of his larvae doing the same thing. And this was actually from a different genus across the world in Japan. So it’s really interesting that it evolved at least twice in these beetles.

IRA FLATOW: So it’s possible that this is more common than you know about.

MATT BERTONE: Yes, and that would be great to find out how common. But again, these are very obscure, little critters that not a lot of people pay attention to.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we have a big audience. So if people are listening, and they want to do some of their own research, can they look for these under the bark of their own trees?

MATT BERTONE: They could. These beetles are associated with kind of micro fungi that are under dead and dying trees, the bark of them. They can be found under the bark of logs on the ground, things like that. They’re not uncommon, and there’s other groups of beetle larvae and insect larvae that would be associated with those fungi. So you’re going to find a lot of different things to observe. If you do that, I would just make sure to be careful to leave some habitat left and to replace bark and things like that to just make sure that the insects and other arthropods have a good home.

IRA FLATOW: Do they have a jumping signature that if I peeled up the bark and I looked and I saw there were a lot of other insects and larvae under there, that I would say, hey, look, it’s jumping in a certain way. That’s the one.

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, so I’d be interested to see, opening up the bark and seeing a bunch of larvae, if you could just sit back and watch and see if they jump. We as scientists would always want to collect those specimens then and get them identified for sure, which was actually the first step of the process, was finding out what type of larva it was, because we actually did DNA work to link it to the adults, and we got confirmation through identification keys. It was really exciting to know that we had seen something possibly the first time and definitely reported for the first time.

IRA FLATOW: You mean the reporting the jumping of it.

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, exactly. So we don’t know without publications whether people have seen it before. Somebody could have just been tearing up a box, saw a little beetle, a little larva or grub jumping around, and thought, ah, well, whatever. But recognizing the importance is really a part of it.

IRA FLATOW: Now I noticed in the video I was watching that you guys went through great trouble to scan the larva, to look at, poke it, see in every direction that you can. Is there still something you don’t know about it that you would like to know?

MATT BERTONE: Yeah, I think we would definitely like to have or would have liked to have more specimens to kind of do some more experiments, like manipulating them on different surfaces or doing different experiments to see what might cause them to do this jumping behavior. Again, they’re very ephemeral. It’s hard to pinpoint where they’re going to be and collect a number of the specimens to experiment on. It’s not like a pest species that’s so common or something that we keep in colonies. So that’s where one of the difficulties comes about.

IRA FLATOW: So you don’t want our listeners sending you their samples that they’re collecting–

MATT BERTONE: I mean–

IRA FLATOW: –from their trees.

MATT BERTONE: I’d love to see some. I mean, I love seeing the diversity of all the things under there. I also don’t want everybody to kind of go out and collecting all these things without kind of proper methods and whatnot. But yeah, I would love to see if people have photos of these things or videos or have the specimens alive, reach out to me, and I’d love to help you identify them. But there are a lot of different ones under the bark, so you may get confused.

IRA FLATOW: OK, well, there you go. There’s the challenge to all of you. If you’ve got something, you can contact Matt at NC State University. Thank you, Dr. Bertone, for taking time to be with us today.

MATT BERTONE: Of course. Thank you very much to you, too.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Matt Bertone, entomologist at NC State University in Raleigh, North Carolina. And if you want to see the jumping larva video I mentioned– and you should because it’s totally worth it– you’ll find it on our website at sciencefriday.com/jumping.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.